Previously: Urban Legend Locations Around The World You Can Find Right On Google Maps.

Not all abandoned places are places that actually permit visitors. A lot of urban exploration happens under the cover of darkness, requiring those interested in it to… find loopholes and get creative, so to speak. But I have good news: There some abandoned places you can actually visit — places you can (mostly) go without worrying that you’re trespassing (or worse). Places you can go that will (again, mostly) actually welcome you when you arrive. Isn’t that nice?

Here, I’ve rounded up 21 abandoned locations that do, in fact, permit visitors, one way or another. Some of them are quire easy to get to, while others… are not; you’ll have to decide for yourself how involved a trip you’re up for. I’ve identified ease of access for each of them as Easy, Moderate, or Difficult to help you along with the decision-making process.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

Additionally, these visitable abandoned places are situated all over the world. Accordingly, I’ve divided the list into two sections: 11 abandoned locations to visit in the United States (since I’m based in the U.S. myself and largely have a U.S. audience), and 10 abandoned locations to visit internationally.

Got the itch to travel? Here are some spots to check out for some arrestingly beautiful ruins and unusual hidden gems:

Within The United States:

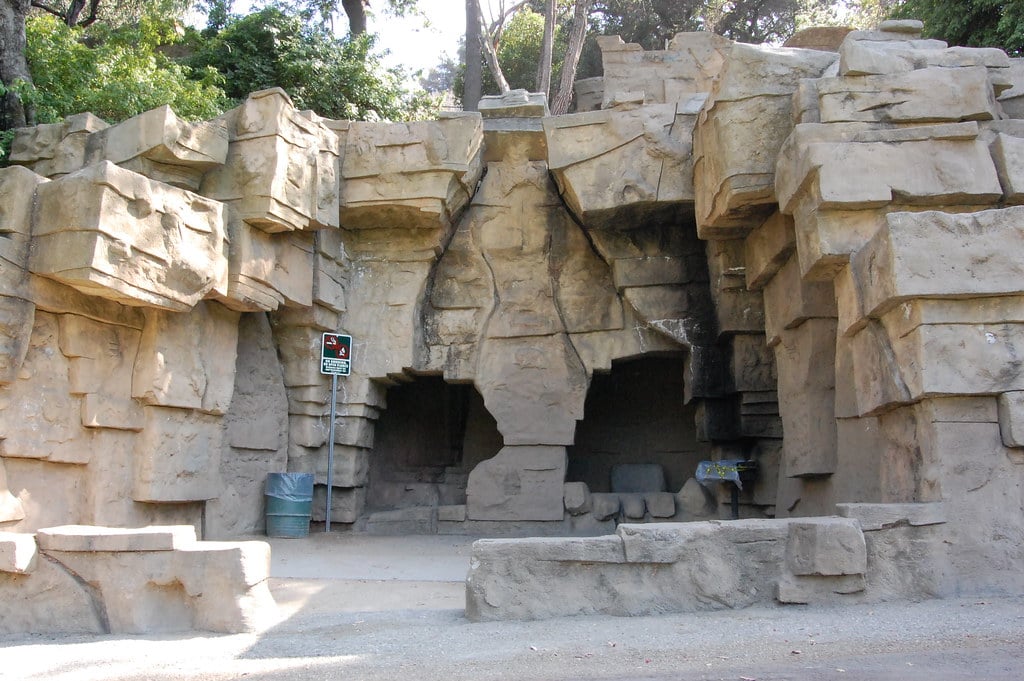

1. The Old Los Angeles Zoo, Griffith Park, California

Not to be confused with the current Los Angeles Zoo, the Old Los Angeles Zoo — sometimes referred to as the Griffith Park Zoo — opened in LA’s Griffith Park in 1912. Trouble was, it had a tiny budget, and, uh, zoos aren’t exactly the kinds of developments you can skimp on. Built on the grounds of what had once been Charles Sketchley’s ostrich farm, the Griffith Park Zoo may have had as few as 15 animals when it opened, mostly cobbled together from animals Sketchley left behind when he relocated his ostriches to the northern part of the state and from a railroad magnate who had kept a “private zoo.”

Conditions were bad at opening, and despite several attempts to turn things around over the decades, the zoo was just too badly built, maintained, and managed to keep it going. In August of 1966, the Griffith Park Zoo was closed, and the animals relocated to the new Los Angeles Zoo, which opened in December of that same year.

Many remnants of the old zoo, however, remain in Griffith Park, including animal enclosures, buildings, and an out-of-commission carousel. They can be freely explored; the large animal exhibits are especially well-maintained these days, and considered by many to be a highlight of a visit to the what’s left of the defunct zoo.

Ease of access: Easy. Griffith Park is a public park, and some of its hiking trails go straight through the remains of the zoo. Picnic tables have even been placed within some of the old animal enclosures, if you feel like having a snack where the tigers used to hang out or what have you. Also, this abandoned place is free to visit — no admission required!

Address: 4801 Griffith Park Dr., Los Angeles, CA, 90027. You’ll probably want to park in Merry-Go-Round Lot #1.

2. Eastern State Penitentiary, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

In 1829, a new kind of prison opened in Philadelphia — one adhering to both a school of thought and an architectural design that hadn’t been seen in the United States prior. Featuring a spoked designed, with wings stretching out from a central hub, it was called Eastern State Penitentiary — so named for its intended function: To inspire penitence through confinement and solitude.

While this idea may sound peaceful in theory, in practice, it was anything but; those confined within its cells were kept isolated from each other in cells lit by only a single small skylight, not permitted to receive any visitors or even letters, and forbidden to speak or make noise. They were also routinely subject to treatment by guards and wardens that was tantamount to torture.

As was often the case for prisons of this era, Eastern State soon became overpopulated; by 1913, it had ceased to operate under the solitary system due simply to a lack of space. It then ceased operations entirely in 1971, at which point it was left to its own devices for some time, gradually being reclaimed by nature and becoming home to a colony of feral cats.

In 1988, efforts to redevelop (read: tear down and build over) the prison were halted, and plans made to preserve it instead. It opened for limited tours while preservation was undertaken, and today, it stands in a state of arrested decay as a museum; its crumbling and overgrown cells interpret the legacy of criminal justice reform in the United States for visitors daily.

Ease of access: Easy. A U.S. National Historic Landmark, the prison is well-preserved and open to visitors from 10am to 5pm every day, excluding some holidays. Admission is $21 for adults and includes guided and self-guided options. Nighttime tours are also available at certain times of year — typically the end of May through the beginning of September — and around the Halloween season, the high-octane haunted attraction Halloween Nights (formerly Terror Behind The Walls) takes up residence inside.

Address: 2027 Fairmount Avenue, Philadelphia, PA, 19130.

3. The Seattle Underground, Seattle, Washington

Fun fact: Parts of the city of Seattle don’t actually sit at ground level anymore. When white colonists arrived in the mid-19th century — displacing Native populations who had already been inhabiting the area for thousands of years — they started building right on the beach. This, however, proved to be a poor decision, and following a variety of issues and incidents ranging from sewage problems to the Great Seattle Fire of 1889, plans were made to raise the streets a full two stories.

But the regrading didn’t just fill everything within those two stories in; instead, it basically created a street below the street: What’s now known as the Seattle Underground. A series of tunnels running beneath Pioneer Square, the Underground was full of shops and businesses accessed first by ladder, and then by more permanent entrances. There was, essentially, a city beneath the city.

The Underground was officially shut down in 1907 due to plague-related fears, although it operated unofficially as a sort of red-light district for some decades afterwards. By the 1940s, however, they were mostly abandoned — until journalist Bill Speidel started researching them in the 1960s, eventually making moves to preserve them and open sections of them up for tours.

Bill Speidel has since left us, but his Underground Tours remain alive and well — and they’re a great deal of fun! I took a tour of the Seattle Underground in 2017 and had a blast. Weird history is the best history — and this weird history may also be a little haunted, too.

Ease of access: Easy. Bill Speidel’s Underground Tours operate every day from 9am to 7pm, April to September, and from 10am to 6pm, October to March. Extra tours of this visitable abandoned place also leave on half-hour from April to September. Tickets are $22 for adults.

Address: 614 1st Ave, Seattle, WA, 98104, in the Pioneer Square area of the city.

4. Collings Castle, Davis, Oklahoma

Turner Falls Park in Davis, Oklahoma isn’t just a lovely place for camping, fishing, swimming, and other outdoor activities; there’s also a ruined castle to explore there.

Well… sort of. Collings Castle was built in the 1930s — that is, despite its seemingly medieval appearance, it’s much more recent than that — and it was a private home, not a seat of power. It belonged to Ellsworth Collings, who was named Dean of Education at the University of Oklahoma in 1926 and held the position for close to 20 years.

The castle, which sits adjacent to the waterfall for which Turner Falls Park gets its name, was the Collings family summer home; it wasn’t huge — according to the Oklahoman, the main house had a few bedrooms and some living spaces, while two bunk houses, two outhouses, and a stable area that was later used as a garage sat nearby — but its architectural style is distinctly regal. Curiously, the interior design scheme was largely ranch-inspired, thanks to Collings’ pet interests, but, hey, whatever works.

Collings died in 1970, after which the castle changed hands numerous times. It’s been owned by the City of Davis since 1977 — and although it hasn’t yet been restored due to a lack of funds, it’s explorable with entry to Turner Falls Park. Tread carefully; it’s not in great shape. But it is, by all accounts, a magnificent sight, even in its decay.

Ease of access: Easy. Collings Castle is open for exploration with admission to Turner Falls Park. Admission prices for adults start at $9 and go up to $20, although how much you’ll pay depends on both the season and whether you go on a weekend or a weekday. It does require a literal hike to get to, though, which looks to be somewhat more strenuous than, say, the walk to the Griffith Park Zoo (see above).

Address: Turner Falls Park is located at I-35 and US Highway 77, Davis, OK 73030. The castle’s location can be seen here.

5. Waverly Hills Sanatorium, Louisville, Kentucky

At the time that it opened in 1910, Waverly Hills Sanatorium was sorely needed: A tuberculosis epidemic was sweeping through Jefferson County, and a huge influx of patients needed treatment. Waverly Hills was supposed to help meet that need — but with space for only 40 patients, it soon reached capacity. And so, it grew, with the original two-story wood administration building and two open-air pavilions receiving company first in the form of a five-story brick and concrete building in 1926, and then, as time went on, with numerous other facilities that essentially made the hospital a self-contained community all its own.

But in the days prior to the development of the antibiotic streptomycin, death came swiftly for many of Waverly Hills’ patients. Thousands of people died on the hospital’s grounds; furthermore, efforts were made to conceal the large-scale death from view, with the remains of patients who passed being transported through the use of a tunnel. These efforts were intended to prevent patient morale from plummeting, but, well… keeping the deaths of so many a secret often comes across as nefarious, once knowledge of it becomes known, rather than helpful. For this reason, the tunnel became known as “the Death Chute.”

By the time Waverly Hills closed in 1961, it was for good reason: Streptomycin had come into use as an effective treatment for tuberculosis, rendering the residential hospital obsolete. A year later, it became a nursing home — but by 1982, it had been shut down due to the discovery of patient abuse occurring within the facility.

Waverly Hills changed hands several times between 1982 and 2001, but eventually, it came under the purview of Tine and Charlie Mattingly. The Waverly Hills Historical Society was established to head up preservation and restoration efforts; the former sanatorium has also now emerged as a premier destination for paranormal investigations.

Ease of access: Easy. The Waverly Hills Sanatorium is open for a wide variety of tours year ‘round, ranging from historical daytime tours to paranormal overnights. The only thing that might make this particular abandoned place a bit prohibitive to visit is the price, depending on what you’re looking for: Regular two-hour historical daytime tours or two-hour nighttime paranormal tours are in the $30-to-$32 range — pricey compared to some of the other ticketed locations in this list — but if you want something more specialized, the price rises accordingly. If you want four hours to photograph the place, for example, it’ll cost you $100, and if you want to book a private overnight investigation, you could end up spending upwards of $1,000 for your group.

Address: 4400 Paralee Lane, Louisville, KY 40258.

6. Lake Shawnee Amusement Park, Rock, West Virginia

In retrospect, it’s perhaps not surprising that Lake Shawnee Amusement Park’s story ended badly; it began badly, too: It was built on the site of a massacre and a mass grave. This gruesome fact wouldn’t be discovered until 1988, when an archeological dig uncovered the remains of 13 humans — mostly children — buried on the property.

When the park opened in 1926, however, this piece of the land’s history wasn’t yet well-known. The plan was for it to be a local spot for wholesome family fun — a place with a Ferris wheel, and a swing, and a dance hall, and more, all set around a picturesque lake. And for a number of decades, it was just that — until the Lake Shawnee Amusement Park shut down in the 1960s.

Why did it shut down? That depends who you ask. In all likelihood, the true story is simply that it failed a health inspection. But there are ghost stories, too — tales that, although unverifiable, still capture the imaginations of many who visit. Tales that insist on tragic accidents occurring on the property — one involving a ride, the other, the lake the itself.

In any event, the property has mostly sat there, rusting, in the decades since, although it’s also become a popular ghost hunting spot. Access is somewhat restricted, but its current owner does offer tours, if you’re lucky enough to book one.

Ease of access: Moderate. As previously mentioned, tours of Lake Shawnee are available, although they’re usually quite limited, only available by appointment and often only at particular times of year. There’s also a Dark Carnival event that occurs annually around Halloween. Your window for visiting might be small, but it’s there. The Lake Shawnee Facebook page is probably the best way to stay on top of what’s available and when.

Address: 470 Matoaka Road, Rock, WV 24747.

7. The Waterbury Fairy Village, Waterbury, Connecticut

In the woods in Waterbury, Connecticut, there’s a teeny tiny village — one that’s definitely not human-sized. It’s usually referred to as either the Little People’s Village or the Abandoned Fairy Village, and it’s quite a peculiar sight.

Built by William Joseph Lannen sometime between 1928 and 1939, the fairy village has a somewhat obscure history. It’s generally believed that Lannen, after scrapping the idea of building a gas station on land he had acquired in 1924 following a traffic diversion, began building the little houses and structures as an attraction to go along with a planned garden nursery he thought to put up instead. However, although he made quite some headway on the tiny village, he had mostly abandoned the venture by 1939, according to a 2020 report from Connecticut Magazine.

To be perfectly, it’s a minor miracle that it’s still standing — but standing, it is, and if you venture into the woods in the right place, you can find Lannen’s tiny village. It’s free to see and walk around, and remains one of Connecticut’s greatest curios.

Ease of access: Moderate. There are no official or legal barriers to the abandoned fairy village; it’s free to visit… as long as you can find it. That’s the tricky part. Per Atlas Obscura, the fairy village can be found on an access road just off of Old Waterbury Road; the access road is overgrown, though, and can only be traversed on foot. You also can’t park on Old Waterbury Road itself — you’ll be towed if you do — so the nearest place to park is a restaurant called Maggie McFly’s. (And, to be honest, the restaurant might not be thrilled to have you park in its lot if you’re not actually going eat at it, so… do with that what you will.)

Address: Waterbury, Connecticut. Here’s where Old Waterbury Road is; you’ll have to figure it out for yourself from there.

8. City Hall Station, New York, New York

The disused City Hall subway station in New York is the true definition of a hidden gem: Gorgeous and ornate, it’s the kind of subway station most of us can only dream about now — and it’s just sitting there, tucked away, visible only if you either ride the 6 train through its turnaround loop at the end of then line, or manage to snag a spot on a much-coveted tour.

Opened in 1904, the City Hall station featured stunning Romanesque Revival architecture, with vaulted ceilings, skylights, colored glass tilework, and brass chandeliers. Its spectacular appearance was fitting, given the fact that it served, well, City Hall; trouble was, it actually ended up not being a particularly useful station. Ridership was low — fewer than 1,000 passengers a day used it — the platform proved to be too short for the evolving, lengthening trains, and when the Brooklyn Bridge stop opened in 1914, the City Hall stop mostly became redundant. The station closed in 1945.

But, like much of the older portions of the New York subway, it remains, present but out of sight. If you know where to look for it, though… it’s truly a sight to behold.

Ease of access: Moderate. The New York Transit Museum offers tours of the abandoned City Hall Station every so often, so in that sense, it’s not difficult to visit; you’re legally allowed in, and you’ll have a guide to usher you along the way. However, actually getting a spot on one of those tours is pretty tricky. They’re only open to members of the museum; they’re only typically scheduled in the fall; there aren’t usually many of them; and tickets, which are $50, tend to go very, very quickly. For more information, head to the New York Transit Museum’s website.

(And for what it’s worth, even if you’re not able to get on one of the City Hall Station tours, the Transit Museum is my absolute favorite underrated destination in New York; it’s where I send people who ask me for my advice as a former New Yorker about what to hit up when they’re in town. It’s worth a visit under pretty much any circumstance!)

Address: Not to be confused with the current, nearby City Hall station on the R and W lines, the old City Hall station is right in the middle of City Hall Park — or rather, underneath it. City Hall Park is contained within the triangle formed by Broadway, Park Row, and Chambers Street downtown; its ZIP code is 10038.

9. Bannerman Castle

Off the coast of Beacon, New York, there’s a mysterious island occupied by the ruins of what was once a spectacular castle. The island is known as Pollepel Island, and the castle is — or was — Bannerman Castle.

Built by Francis Bannerman IV in the early years of the 20th century, the castle itself actually wasn’t meant to be a residence; it was a storehouse for surplus munition cartridges. Bannerman, you see, was one of a line of Bannermans to operate a military surplus business — and he needed somewhere safe (e.g., unpopulated) to store excess munitions. Bannerman put plans for the castle in place to serve this purpose, along with those for a smaller residence for him to actually occupy when he was on the island.

Bannerman died in 1918 — and then, just two years later, the powder exploded. A couple of decades after that, the ferry that serviced Pollepel Island sank, and for some time, both the island and the castle were left to their own devices.

Over the past several decades, though, the Bannerman Castle Trust has put much work into preserving the castle, the island, and everything else that can be found on the grounds. It’s now open for tours and events, and makes for a stunning photography location.

Ease of access: Moderate. Tours and other events — movie nights, themed dinners, theatrical productions, and more — are plentiful and easy to book. The standard Bannerman Castle guided cruise and walking tour — which is the tour I took way back in 2014 — is $40 for adults; tickets to live performances, meanwhile, tend to run around $70 to $80, and themed dinners ring in at a whopping $300. Besides the prices, the only thing that makes Bannerman Castle a little difficult to access as an abandoned place is that it’s quite a trek to get there.

Address: Pollepel Island, off the coast of Beacon, New York.

10. Bodie, California

Want to explore a real, live ghost town? Bodie, California is one of your best options. It’s excellently preserved and open to the public… as long as you’re able to make the journey to it.

Signs of gold were first discovered in Bodie in 1859 by its namesake, a prospector called W. S. Bodey. But, just like Bodey, who died in a blizzard in 1860, the town of Bodie had decidedly mixed fortunes over the years: Booming, busting, and booming again as the Gold Rush went on, it was firmly on the decline by 1910, with the last mine shutting down in 1942.

There’s good news, though: In 1962, Bodie was designated as a National Historic Site and a State Historic Park, and its remaining buildings preserved in a state of arrested decay. There are roughly 100 buildings still standing, which, although only a small portion of the town at its height, together offer a shockingly complete view of the place.

It also might be haunted. Maybe.

Ease of access: Difficult. As a State Historic Park, Bodie is open to visitors; admission is $8 for adults, with summer hours typically being 9am to 6pm daily. It is, however, difficult to get to, due to the unpredictability of road conditions. Per the Bodie State Historic Park website, the last three miles of the road to Bodie are unsurfaced and “can at times be rough.” Additionally, although Bodie is open year ‘round, it’s only accessible by skies, snowshoes, or snowmobiles during the winter, and in the spring, mud can apparently “be a problem.” Towing services are also not always reliably accessed in the area, and generally very expensive. Plan your trip accordingly.

Address: Highway 270, Bridgeport CA 93517.

11. Centralia, Pennsylvania

You’re probably familiar with Centralia, but in case you’re not, here’s the TL;DR: The coal mines beneath Centralia went up in flames in 1962, and haven’t stopped burning since.

Although Centralia has quite a long history, the coal deposits in the area that would eventually give it its infamous reputation were mostly left alone until the 1840s. That’s when the Locust Mountain Coal and Iron company acquired the land which would later become Centralia and began making preparations for a large-scale coal mining operation. Mining engineer Alexander Rae, who worked for Locust Mountain, moved his family to the area to oversee the mining operations, and the town built up from there.

After the fire started, though — and after it became clear there was literally nothing to be done about it but let it burn — Centralia became largely unsafe to live in. High carbon monoxide levels, unstable ground and surprise sink holes, and other structural issues have abounded ever since, leading most residents either to move away of their own accord, or to accept relocation compensation from the government. Centralia has been left there ever since, looking like a post-apocalyptic landscape and lending its eerie inspiration to things like the design of the movie adaptation version of Silent Hill.

Some folks still live there, though. They sued for their right to stay, and in 2013, they were granted that right. Change is hard, even as the town you called home literally burns away beneath your very feet.

Ease of access: Difficult. Admittedly, Centralia isn’t as difficult to get to as Bodie — but it’s also not officially open for visitors, meaning you’re taking a bit of a risk if you decide to go. The big thing to keep in mind is that, although roads pass through it that are, in fact, open to traffic, most of the buildings and what remains of the town are either owned by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania or are private residences. Mind any signs or barriers you see, and don’t be a jerk.

Address: Centralia doesn’t have a ZIP code anymore — it was revoked in 2002 (for the curious, it used to be 17927) — so you’ll have to rely on tools like Google Maps to find it. You can see it here.

International Locations:

12. Anping Tree House, Tainan City, Taiwan

The moniker “Anping Tree House” doesn’t refer to a structure built in the branches of a tree. It refers to a structure through which trees have shot up on their own. Get it? Tree house?

Located in Tainan City in Taiwan, Anping Tree House was once a warehouse built and used by the Tait & Co. trading company during the era of Qing dynasty rule in Taiwan. Tait & Co. was a British training company; Anping was opened as one of Taiwan’s trade harbor at the time. Tait & Co. primarily traded sugar and camphor, with the warehouse being built to store the goods before they were loaded up and shipped out.

The Japanese takeover of Taiwan in the late 19th century, however, put an end to foreign merchant trade operating within the country. After Tait & Co. vacated the warehouse and its accompanying merchant house, the buildings were used for the Japan Salt Company — and then, after Taiwan was handed over to the Republic of China, the merchant house came into use by Taiwan Salt Works.

The warehouse, however, was abandoned — and as time went on, the roots of the banyan trees grew up and through it, turning the former warehouse into a literal tree house. In 2004, it opened up as a tourist attraction, and has remained a unique and popular sightseeing spot ever since.

Ease of access: Easy. The Anping Tree House is located in an area full of historical sights, making it a terrific stop on a trip to this area of the Tainan City. According to travel writer Nick Kembel, it’s accessible by public transportation, with the most convenient buses from the city center being Taiwan Tourist Shuttle 99 and Tainan City Bus number 2. The grounds are open daily from 8:30am to 5:30pm, with tickets running about 50 NT, or about $1.60 USD.

Address: 108 Gubao Street, Anping District, Tainan City, Taiwan.

13. Paronella Park, Mena Creek, Queensland, Australia

If you’re looking for something to do in Australia that combines the beauty of a botanical garden with the fun of a theme park and an eye-catching piece of splendidly overgrown architecture, Paronella Park might right up your proverbial alley.

The history of the park is a winding one — but at the center of it is one man: José Paronella. A Spanish immigrant, he departed Catalonia headed for Australia in 1913 and set about building a life not just for himself, but for his fiancée, as well. He had been engaged when he left Spain, and meant to bring his intended to live with him in Australia eventually, as well.

When he returned to Spain in 1924, however — more than a decade after he had left — he found his fiancée had married someone else in his absence. So, he wooed and eventually married his original fiancée’s sister, Margarita, and returned with her to Australia in 1925.

In 1929, he bought a piece of property along Mena Creek he has previously seen and fallen in love with, and proceeded to build a home for his family — first a cottage, then a full-on castle and entertainment park including a space that functioned as both a movie theater and a ballroom, tennis courts, a pavilion with turrets and balconies, refreshment rooms, changing cubicles for those wishing to swim, and even a museum full of curios Paronella had collected over the years.

Paronella Park was quite successful in its day, and after José Paronella’s death in 1948, his wife, children, and grandchildren continued as caretakers until 1977. Alas, though, in 19787, a fire destroyed much of the castle, and a cyclone in 1986 caused more structural damage.

In 1993, however, it was purchased by Mark and Judy Evans, who set to work restoring the place. Now, it’s a major tourist attraction, full of beautiful gardens, a museum, and of course the castle, no longer habitable, but maintained in a stunning state of arrested decay.

Ease of access: Easy. Paronella Park is open to the public daily from 9am to 7:30pm, excluding some holidays. Admission for adults starts at $55 AUD, or about $37 USD.

Address: 1671 Innisfail Japoon Rd, Mena Creek QLD 4871.

14. Yongma Land, Seoul, South Korea

If you’re a K-pop or K-drama fan, you’ll probably recognize photos of Yongma Land when you see it, if you’re not actually aware that it’s Yongma Land: The shuttered amusement park has become iconic in recent years, thanks to its use as a shooting location for things like the music video the Crayon Pop single “Bar Bar Bar” and the K-dramas The Sound Of Magic and Sisyphys: The Myth.

This small family park originally opened in the 1980s, when South Korea’s economy was in a major upswing. Unfortunately, though, it was only successful for a short while; a combination of competitors like Lotte World opening up in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s and the looming financial crisis that would arise in Asia in 1997 resulted in Yongma Land’s failure to maintain its popularity. It limped along for some time regardless, but in 2011, its license to operate as an amusement park was pulled, and it’s mostly been situated in a state of arrested decay every since.

But in recent years, it’s become a tourist attraction not in spite of its ruin, but because of it. It’s known as “the amusement park where time has stopped,” and if you visit it, you can see the fading glory of a 1980s family amusement park, perfectly preserved even as it rusts around the edges.

Don’t miss the carousel; it’s particularly gorgeous.

Ease of access: Easy. Daily visitors are welcomed to this abandoned place for a nominal admission fee — usually around 10,000 won for adults, or roughly $7.90 USD. It’s even accessible by public transportation: Take the train to Mangu station, then either walk, take a 15-minute bus ride, or call a cab. There’s a ticket booth at the second gate where you can either pay up if it’s staffed, or call a phone number usually listed at the booth and someone will come out to meet you. You can even book it for private photography sessions. Note that it’s worth calling ahead to make sure the park is open to the public and not reserved for a private session or event the day you plan to go.

Address: 118 Mangu-ro 70-gil, Jungnang-gu, Seoul, South Korea.

15. The Great Train Cemetery, Uyuni, Bolivia

Uyuni, Bolivia is widely known for being the gateway to the largest salt flat in the world — and if you take a trip out to see that salt flat, you can also see the place that trains go to die: The Great Train Cemetery, or the Cemeterio de Trenes.

Uyuni sprang up in about 1890, where it formed a convenient intersection of rail lines for Bolivia itself, as well as Chile and Argentina. Why were the rail lines important? Because mining was important. You’ve got to be able transport all that ore out once you’ve found it right?

But guess what happened after the mining dried up? So, too, did the need for train transportation in the area. So, in 1940, the trains were discontinued — but they also weren’t moved. They were just left where they were, and there they remain to this very day. Over 100 train cars, most from the early 20th century, lie like beached whales, slowly corroding under the onslaught of so much salt.

Ease of access: Easy-ish. There are loads of companies that offer tours of the salt flats, and nearly every single one of these tours includes a stop at the train cemetery. If you don’t want to book a tour, though, it’s also still pretty easy to get to once you’re in Uyuni — it’s right on the outskirts of town, only about a 10-minute drive from where most of the hotels are located. If you go on your own, you’re best aiming for early morning (before 8am) or sometime in the evening (after about 5pm) to avoid the tour company crowds.

Address: Uyuni, Bolivia. There’s no precise address, per se, but there’s signage, and according to Rana Good writing in Forbes, locals will often be able to point you in the right direction. The location can be seen on Google Maps here.

16. The Crystal Palace Subway, London, England, UK

The Great Exhibition was big news when it opened in London in 1851; a massive display of culture, art, and industry, it set the standard for the myriad World’s Fairs that occurred for generations after. Naturally, such an astonishing sight required an equally astonishing venue; to fill this need, a huge, plate glass and cast-iron structure was built in Hyde Park. It didn’t stay there, though; after the exhibition’s conclusion, the structure was moved to Sydenham Hill — and when it did, new transportation options were required to service it.

What’s now known as the Crystal Palace Subway was one of those options; it offered pedestrians a path beneath the Crystal Palace Parade. Designed with the high arches and octagonal stone pillars of an Italian cathedral and a warm red and cream color palette, it was as much an attraction as the Crystal Palace itself — but after a fire destroyed the Crystal Palace in 1936, both the Crystal Palace Subway and the Crystal Palace High Level rail station were rendered obsolete.

The High Level station was eventually demolished, although the Subway remained, often reappropriated for different uses over the years: It was an air raid shelter during the Second World War; children used it as a playground in the decades after; and so on. Eventually, though, it was deemed a safety risk and walled up during the 1970s.

Later, though, an organization formed to preserve the subway and bring it back to life: The Friends Of Crystal Palace Subway. A huge amount of restoration work has been undertaken in the years since, with still more in the works now.

Ease of access: Easy to moderate. Like the City Hall station in New York, the Crystal Palace Subway is occasionally open to tours; the Friends Of Crystal Palace Subway have administered these tours a few times a year since 2016. In 2022, however, a major restoration project was begun, keeping the subway closed until the work is complete. It was originally projected to finish in July of 2023, although it remains ongoing. So: By “easy to moderate,” I mean that it’s fairly accessible, but only at select times, and not at all until the restoration work is complete.

Address: Crystal Palace Parade, London SE19 2BA, United Kingdom. According to the Friends Of The Crystal Palace Subway, its entrance is just inside the park, located between bus stops B and W.

17. Hồ Thuỷ Tiên Water Park, Huế, Vietnam

In 2000, construction began on what was meant to be a huge, elaborate, outdoor entertainment complex in Huế, Vietnam: Hồ Thuỷ Tiên, a tourism destination set to include a sculpture garden, an amphitheater, an aquarium, villas, a water park full of slides and rides, and much, much more. At the center of it all was to be a huge, stone dragon set in the middle of a lake, reachable by a long bridge and housing the aforementioned aquarium. It would be a place to escape for a few days, to enjoy a little luxury on a mini-getaway or weekend trip.

In 2004, something resembling this grand vision opened… but not the vision in its entirety. An astonishingly expensive project, only parts of Hồ Thuỷ Tiên had ultimately been built — and what’s more, due to poor management, low attendance, and increasingly costly operation expenses, the whole complex had shut down by 2011.

But it wasn’t demolished. The parts of Hồ Thuỷ Tiên that had been built are still there, gradually becoming more and more overgrown — and visitors have become more and more common over the years, as well. The remains of the water park are typically the main draw for those who might like to see the place, with the colorful tubes and slides popping out from the green of the jungle surrounding them in a eye-catching display of bright, bold decay.

And the dragon? It’s there, too, rising up out of the lake, majestic even as it crumbles, bit by bit.

Ease of access: Moderate. It’s not exactly forbidden to visit Hồ Thuỷ Tiên… but nor is it entirely on the up-and-up. Getting to this abandoned place you can actually visit is probably the most challenging part; most guides recommend either renting a motorbike to get yourself there, or just hiring the services of a car and driver. There may or may not be a guard at the gate, who may or may not collect a small “admission fee” from you before allowing you in. Once you’re there, though, you’ll likely be able to wander freely, and will also likely see many other visitors doing the same. For the curious, here’s where it’s located.

For what it’s worth, an announcement made in 2022 stated that the government planned to renovate Hồ Thuỷ Tiên and officially reopen it in March of 2023; however, as of this writing, those plans have not yet come to fruition. It’s not clear what the current status of the project is.

Address: CH5H+5CG, hồ Tiên, Thủy, Thủy Bằng, Hương Thủy, Thừa Thiên Huế, Vietnam.

18. Hashima Island, Nagasaki, Japan

Hashima Island, also sometimes called Gunkanjima or Battleship Island, has become pretty widely known in recent decades, thanks to the fact that it’s served as a shooting location for a variety of high-profile screen projects: The History Channel’s 2009 series Life After People, for example, and the 2012 James Bond flick Skyfall. But it’s been around for much longer than that — and, like a few of the other ruins on this list, its history is quite dark.

In the early 17th century, coal was discovered on the island, leading it to become a major mining spot for close to a century. The mining operation was run by Mitsubishi for most of that time; the company purchased the island in 1890, with mining continuing until 1974.

Beginning in about 1916, miners and other workers actually lived on the island, as well — but not always willingly: During the Second World War, Chinese prisoners of war and conscripted Koreans made up the bulk of the workers as forced labor. Many also died under these circumstances.

During the 1960s, Japan began shifting from coal to petroleum as its main source of fuel; as such, coal mining operations began closing down all over the country — including the coal mining operation at Hashima Island. It finally shuttered in 1974, and the island abandoned.

Eventually, though, it came under the administration of the government of Nagasaki city, and in 2009, tourism to the island opened up. If you’d like to see what the world might look like if humans died out and left everything to its own devices, a trip to Hashima Island might paint that picture for you.

Ease of access: Moderate. Hashima Island is open to the public; you just can’t go there on your own steam. Access to the island is heavily regulated, and visits must be done in coordination with an official tour. Since it requires some planning, I’d consider it a moderately complicated trip to make. Options include Gunkanjima Cruise, Gunkajima Concierge, and Gunkajima Landing and Cruise. You’ll typically pay a boarding fee to the tour company you use — usually something in the neighborhood of 3,000 to 4,000 yen, or about $20 to $30 USD — and a “landing fee” of 310 yen, or about $2.25 USD, to actually set foot on Hashim Island, charged by the city of Nagaski.

Address: Takashimamachi, Nagasaki, 851-1315, Japan.

19. The Island of the Dolls, Xochimilco, Mexico

The Island of the Dolls, or la Isla de las Muñecas in the original Spanish, isn’t actually an island—not really. It’s a chinampa — a human-made land mass built and utilized by the Aztecs as floating gardens for crop cultivation. But although there are many chinampas in the Xochimilco area of Mexico, south of the center of Mexico City, la Isla de las Muñecas is one of a kind: It is full — full — of dolls.

They didn’t just appear, of course; they were put there by someone: Don Julian Santana Barrera, who moved to the chinampa in the 1950s after having exiled himself from both his family and society itself. And once he was there, he began scavenging huge amounts of dolls and hanging them from trees, nailing them to the sides of his cabin, and mounting them on stakes.

There are many stories about why he may have begun collecting and hanging the dolls; the most prevalent is that he was plagued by the spirit of a young girl haunting the chinampa and displayed the dolls in an effort to keep her appeased. Ultimately, though, the whys and wherefores remain unknown — and Barrera will never be able to tell us himself, either: He died in 2001, taking his reasoning to his grave.

In the years since his death, however, the Island Of The Dolls has become quite the tourist spot; it’s true that it might not be quite as eerie when crowded by sightseers, but it’s still an arresting sight, for those looking for something a little off the beaten path to do when visiting Mexico City.

Ease of access: Moderate to difficult. Boats do go to the chinampa, but figuring out which ones do, and making sure you actually get taken to the correct chinampa, can apparently be tricky. Most tourism sites recommend heading to either Embarcadera Cuemanco or Embarcadero Fernando Celada in Xochimilco, asking around at the dock, and booking a boat — one of the trajineras — to take you either on a tour of the canals in general, or to la Isla de las Muñecas specifically. The boats are usually booked by the hour, with a trip taking anywhere between two and six hours; you should probably plan on the trip costing at least 1,400 pesos, or about $85 USD.

Address: Xochimilco, Mexico City, Mexico.

20. Poveglia Island, Venice, Italy

Venice is surrounded by small islands. They’re all beautiful and picturesque — but one of them has a dark past: Poveglia Island, also known as the Plague Island.

Poveglia’s history is ancient (as is the case for much of Italy); the earliest reference to it that we know of was recorded in 421 BCE. Many centuries later — the 1700s — it became a checkpoint for ships arriving to and departing from Venice… but in 1793, after an influx of ship-born plague, it was transformed into a quarantine location for mass quantities of those who had fallen ill. It was sealed off, later becoming a permanent quarantine zone in 1805.

After the danger from the plague had passed, Poveglia’s identity changed again, this time becoming a hospital for the elderly in 1922. The hospital was shut down in 1968 for ethics violations, however. And ever since then? Well, it’s just been hanging out there in the Venetian Lagoon, decaying hospital facilities and all, gradually gaining a reputation for being the most haunted island in the world.

Ease of access: Moderate to difficult. It’s sometimes difficult to determine whether Poveglia actually is a visitable abandoned place at any given time. It’s definitely not just open to the general public, but a variety of boat tour companies in Venice offer routes that include Poveglia. Here’s one option, for instance; here’s another; and maybe try here, as well.

Much of the time, it seems that all they can do is drive past Poveglia — meaning you’re not allowed to disembark and actually explore the island — but even viewed slightly afar from a boat, it’s still quite a vision. Some companies have tours that are specially focused on Poveglia, like this one from Il Bragozzo, although you’ll have to contact the company directly to find out whether the route just takes you around Poveglia, or actually to Poveglia.

Address: Venice, Italy.

21. Houtouwan, Shengshan, China

“Abandoned” is perhaps not quite the right word for Houtouwan; people do still live there. The population is less than a dozen now, though — a far cry from the 3,000 that called Houtouwan home in the 1980s.

Once a prosperous fishing village, Houtouwan’s remote location proved to be difficult to manage as time went on. Additionally, with large-scale fishing operations ramping up in nearby — and more accessible — Shanghai, villagers began to move away for better prospects elsewhere during the 1990s. Houtouwan was officially depopulated in 2002, and although a small handful of residents remain even today, the village is largely vacant — and, accordingly, full of houses disappearing bit by bit under the wild growth of greenery and nature.

But in 2015, photos of the village went viral — and, after several years of work implemented in order to build up the infrastructure required for tourism, it now welcomes visitors. There’s an $8 nominal admission fee to hike around the village and see it’s leafy, abandoned, and sometimes still furnished houses; additionally, a viewing platform provides sweeping views of Houtouwan from afar for a fee of $3. Bed and breakfasts have also opened up near the village, although not inside it, making overnight stays doable.

Ease of access: Difficult. Tourists are welcome; Houtouwan is just a bit challenging to get to. Per CNN Travel, ferries to nearby Gouqi Island are limited; the most doable one is usually the 9:25am ferry departing daily from Shenjiawan Pier in Shanghai. You’ll have to get your ticket at Shanghai Nanpu Bridge Tourism Center first, though, and then take the 7:15am bus from there to the pier. The bus ride is about a one-and-a-half-hour trip, while the ferry ride is about three and a half hours. Once you get to Gouqi Island, local taxis provide service over the bridge to Houtouwan.

Address: Houtouwan, Shengsi County, Zhoushan, Zhejiang, China.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Bluesky @GhostMachine13.bsky.social, Twitter @GhostMachine13, and Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And for more games, don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via Arquitecto Defecto, Adam Jones, Ph.D. – Global Photo Archive, anyjazz65, ConspiracyofHappiness, juliandunn, s.c. analog & digital, formulanone, riNux, lancochrane, Crash Test Mike, Luigi Tiriticco, Nuno Luciano/Flickr, available under CC BY 2.0, CC BY-ND 2.0, and/or CC BY-SA 2.0 Creative Commons licenses; Lucia Peters (2)/The Ghost In My Machine; Lily O’Sullivan/YouTube; Christian Bolz, LBM1948, Peter Cooper, Jordy Meow, Wa17gs/Wikimedia Commons, available under CC BY-SA 4.0 and/or CC BY-SA 3.0 Creative Commons licenses]