Previously: FaceTheLight, The TikTok Ghost Story.

Marble Hornets, Hi I’m Mary Mary, Daisy Brown — if you’re interested in horror web series, these are all titles with which you’ll undoubtedly be familiar. But for every huge, spooky, YouTube phenomenon with an audience of thousands, there are dozens of smaller web series that break only a few hundred views. Chip Time is one such YouTube series: Uploaded between Aug. 1, 2016 and Feb. 26, 2018, this spooky computer game-based tale has gone mostly unnoticed the entire time it’s been around. Indeed, despite getting some attention from a handful of dark media YouTubers in the past year or so, Chip Time’s subscriber base still only totals 572, with most videos having a view count of 300 to 700 views.

There’s a probably a reason for the lack of interest (besides the fact that getting noticed or going viral on the internet is sort of a crapshoot): Chip Time is, in all honesty, not a particularly original piece of work. It does get bonus points for not using identifiable monsters that already exist — e.g. it’s not another Slenderman story — as well as for the creation of the Chip Time software itself; the actual execution, though, is a little lazy at times — and, more importantly, the series lacks originality in just about every other way. Structurally, thematically, and plot-wise, Chip Time follows nearly every single convention codified by all of the notable Spooky YouTube Web Series that came before it, and it hits every single beat you’d expect a Spooky YouTube Web Series in this vein to hit.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

At the same time, though, that, I think, is actually what makes Chip Time worth looking at. It doesn’t represent any new strides being made in the genre, but it does represent the solidification of what’s now considered to be the Spooky YouTube Web Series Formula — that is, it functions as evidence of the cementation of the Spooky YouTube Web Series Formula in the cultural zeitgeist. Furthermore, it occupies an interesting spot in the developmental timeline a specific subgenre of online horror storytelling, as well: Those based around odd, unusual, or haunted video games. Created after BEN Drowned and Sad Satan, but before Petscop, Chip Time represents a step between the first two and the last one in terms of narrative structure.

Chip Time, Briefly

Chip Time features two nesting narratives. One is the story of Simon and Jill, a couple in their early 20s who move into an apartment, find a weird floppy disk in a cupboard while they’re unpacking, and subsequently suffering a whole bunch of horribleness that eventually results in both of their disappearances. Meanwhile, the second is the story of Blake, who had become friends with Simon online and, after making plans to meet up with Simon in person for the first time, discovers both Simon and Jill to be missing.

The videos that make up the series ostensibly come from several sources. The main one — the one that provides the vast majority of footage of Simon and Jill — is a hard drive Blake has found in the couple’s abandoned apartment; the footage from this source is understood to have all been shot by Simon. Blake also periodically uploads footage he recorded himself — videos that document his trips to Simon’s apartment and so on and so forth. And, later on, we begin getting footage shot from Jill’s perspective when Blake unearths her phone, which had been lying on the floor of the bedroom in the abandoned apartment. By sifting through all of Simon’s and Jill’s footage and uploading it to YouTube, along with his own observations about the footage and occasionally a video or two of is own, he hopes to figure out what happened to his friend.

The question, though, isn’t just about what happened to Simon and Jill. It’s also about what might happen to Blake if he digs too deep.

The series isn’t terrible long; the 26 videos which comprise it range from about one and seven minutes in length apiece, with the total amount of content coming out at about 98 minutes — roughly the length of a feature film. But a lot happens in that 98 minutes: Simon becomes obsessed with the game he finds on the floppy disk (the titular Chip Time); the couple begin experiencing odd events in their apartment which seem to indicate the presence of something supernatural; they begin recording their daily lives on video in an attempt to figure out what’s going on; Simon’s behavior becomes increasingly erratic as he spends more and more time with both Chip Time and, inexplicably, an abandoned house or other structure out in the woods; we find out through one of the videos that someone else seems to be living in Simon and Jill’s apartment with them without their knowledge; and, eventually, Simon falls prey to whatever force has been stalking them and, seemingly, trashes the apartment and abducts Jill.

Blake, meanwhile, eventually begins to see the same audio and visual distortion in the footage he shoots that Simon and Jill saw in theirs before they vanished.

Again, the storytelling throughout the series is somewhat lazy at times; it also leaves too many threads unresolved. We never learn, for example, what the deal is with the building in the woods, why Simon is so preoccupied with it, and who the unidentified man he runs into while exploring it is. We never learn what the deal is with the additional person who is (maybe) secretly living in Simon and Jill’s apartment with them; I’m assuming that this person is responsible for putting the Chip Time disk in Simon’s view in Upload 17 (notice that the cupboard Simon finds the disk in is closed the first time we see it, but open the second time, after Simon and Jill have gone outside for a moment) — but we find out nothing else about them. We never find out the significance of the various names mentioned by the Chip Time software itself in the segments documenting Simon’s explorations with it. (Who are Kevin, Andrew, and Jim?)

Why are there so many loose ends to in Chip Time? My sense is that the story just spread itself out too thinly, trying to incorporate too many mysteries and ultimately needing to abandoned many of them due to time or budget constraints (or both). But despite all of these loose ends, there’s still something compelling about the whole thing — and that’s largely because it was basically following the unofficial rule book of How To Make A Spooky YouTube Web Series.

Slenderman, YouTube, And The Rise Of A Formula

People have been using YouTube to tell horror stories that blur the lines between fact and fiction almost since the platform’s very beginning. YouTube officially launched in December of 2005; Lonelygirl15 uploaded its first video in June of 2006; and In The Dark (aka Louise Is Missing, aka the Louise Paxton mystery) launched in April of 2007. But it wasn’t until 2009 that the real game changer occurred: On June 10 of that year, Eric Knudsen, writing under the name Victor Surge in a SomethingAwful thread titled “Create Paranormal Images,” unleashed Slender Man on the world.

Slender Man (or Slenderman, as he’s sometimes known) captured the internet’s attention in a way that few things do, and although the character is not technically in the public domain, hundreds and hundreds of people took the idea of him and ran with it. Together, the internet’s hivemind built a complex, sometimes contradictory, and ever-expanding mythos perfectly suited to the storytelling tools the advancement of technology had given us — so it was, of course, only to expected that YouTube would become a huge part of the Slenderman phenomenon.

Marble Hornets was the first of the lot; the very first video of the series was uploaded on June 20, 2009, just 10 days after Slenderman’s SomethingAwful debut. EverymanHYBRID came next, with its first video arriving on March 21, 2010. Then came TribeTwelve, launching on June 5, 2010, and then Dark Harvest, kicking off on Nov. 26, 2010. These early Slenderman series became hugely influential, ushering in a particular era of online horror storytelling characterized by its use of found footage as a genre and a number of particular tropes and conventions.

Marble Hornets, for example, starts with someone who has gone missing (Alex) and takes the form of a narrator character (Jay) sifting through footage left behind by the missing person in an effort to find out what had happened to them. The narrator, too, eventually gets drawn up into the whole thing, with the implication being that whatever had gotten the missing person was coming for them him next.

TribeTwelve is similar, although instead of someone going missing, someone has died.

All four of these series deal closely with characters who come under the influence of dark forces, causing them to engage in increasingly uncharacteristic behavior, often culminating in them harming the people they love and care about.

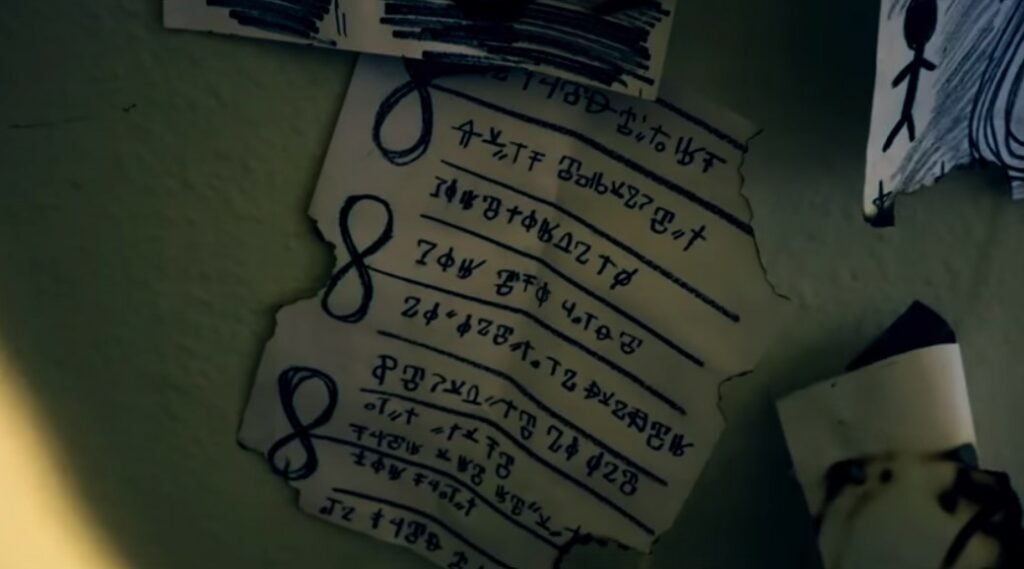

Another common trope: Disordered environments reflecting disordered minds. Trashed rooms, with upended furniture and piles of detritus on the floor. Darkness — curtains closed, lamps malfunctioning or turned out, light removed from the space. Symbols, pictures, and code characters, strewn about, scribbled on crumpled-up pieces of paper and taped to the wall or left on the floor.

Notably, these destroyed environments often belong to apartments or houses — that is, they are homes which are then made unheimlich, un-home-like.

Oh, and those dark forces mentioned earlier? They nearly always make themselves known in the same way: They cause severe audio and visual distortion in any video footage recorded when they’re around.

Each of these series, of course, has their own unique take on the genre; the set-up for EverymanHYBRID is very different from the set-up of Marble Hornets, for example, and every single one of them has different twists and turns. And yet, in looking at these series as a group, it’s still apparent that there’s something of a formula there — or, more accurately, that these series created and codified that formula in the first place. And by the time Chip Time came around, The Formula had become a known quantity — a sort of road map that could be followed in order to tell similar stories.

Which is, in fact, precisely what Chip Time does. Begun in 2016 — many years after Marble Hornets and the bunch — it employs those same elements assembled in roughly the same way to tell essentially the same story that its predecessors did: Someone has gone missing; someone has found the missing person’s footage; the footage reveals the presence of a dark force through audio and visual distortions; the missing person becomes deeply influenced by this dark force; a terrible fate befalls the missing person and someone close to them; and now, the dark force seems to be coming for the person who found the footage next.

The main difference, of course, is that the core of Chip Time is a computer game — and it’s here that the series gets a bit more interesting from a theoretical standpoint.

Video and computer games have factored prominently in online horror fiction for some time; indeed, some of the earliest creepypastas, such as the “The Theater,” the Pokemon-centric “Lavender Town Syndrome” stories, and the NES Godzilla creepypasta center around pieces of software with unusual or supernatural qualities. But few go so far as to actually create the video games around which these stories are built — which makes those which did stand out among the bunch.

The three that stand out the most to me are stories we’ve talked about here at TGIMM before: BEN Drowned, which initially began on Sept. 7, 2010; Sad Satan, which first hit the internet on June 25, 2015; and Petscop, which began uploading on March 12, 2017. In 2018, when I finally decided to tackle the whole Sad Satan mystery, I made the argument that Sad Satan effectively bridged the gap between BEN Drowned and Petscop in terms of the way the storytelling worked.

Now, though, I think there’s actually another step in there: I think Chip Time bridges the gap between Sad Satan and Petscop. Not literally, perhaps — Chip Time’s viewing numbers are so low that it’s highly unlikely that Petscop’s creator, Tony Domenico, ever saw it. But as a microcosm for horror-centric fiction utilizing video games as part of its storytelling mechanism and where we’ve been with that the idea at specific points in time? That’s where I think it’s notable — and that’s why I think it’s significant, despite the many flaws in its execution.

Chip Time, Gameplay, Video, And Narrative

Where Chip Time the series really shines is in the segments featuring Chip Time the game. The simple fact that the game exists is a feat of which its creator or creators should be proud: Building a functional piece of software specifically for use in a series like this one is no small thing — and the same goes double for one that drives the story forward in the way that this one does. The level of detail in the software just makes it even more notable; designed to look, feel, and work like an old-school, DOS-style computer game, it nails the realism in every conceivable way.

Based on the two logos we see when the game boots up in Upload 18, which shows Simon’s first forray into Chip Time, it seems to have been a collaboration between the UC university system and a fictional developer called Clamber Software. We can’t see a copyright year anywhere, but judging by the graphics, it’s probably meant to have been made in the 1980s; it closely resembles titles like Bumble Games, Kindercomp, and other similar educational games released during that decade. (Bumble Games and Kindercomp were both released in 1983, for what it’s worth. Chip Time also lacks the comparative visual sophistication that ‘90s-era educational games have, which, again, supports the idea of it being a product of the ‘80s.)

But Chip Time doesn’t just look like an ‘80s-era educational came; it operates like one, too: It’s composed of a series of mini-games, each relatively unsophisticated and operated via keyboard. Options include “Treasure Man,” which is essentially a Pac Man clone; “Space Probe,” in which you pilot a little ship around the screen in order to collected gems; and “Shape Dodge,” which involves moving a small circle around the screen while you attempted to dodge other shapes moving around you.

And then there’s “Ask Chip.”

“Ask Chip” appears (on the surface, at least) to be a simple AI chatbot. The feature is entirely text-based — that is, there’s no graphic component, the way there is with the other Chip Time mini-games — and functions the way, say, Infocom’s text adventure games did, or the way that instant messenger chatbots like SmarterChild would later on.

Except… something is very obviously Not Right with “Ask Chip.”

The first time we see Simon interact with it is clearly not the first time he’s ever played it; by that point — Upload 4 — he’s looking for some specific answers involving specific terms he already knows the bot to use. He wants to know what “integration” is, to which Chip replies, “Perfect systems don’t exist. Integrate until it’s right. Integrate, extract, remove, retract. Integrate until it’s right.”

We can’t make much of this when we initially encounter it — its place in the narrative is intentionally out of sequence — and the same is true for what we see in Upload 9, “Another Conversation.” but when we do finally see Simon’s first outing with “Ask Chip” in Upload 17, we learn a great deal. We learn, for example, that whoever or whatever is behind Chip Time has actively target Simon specifically: When Simon opens up “Ask Chip” in Upload 17, it already knows his name. Indeed, it welcomes him back by name, and won’t let him use the “Not SIMON? Type NOT SIMON” command the game states can be used by people who aren’t Simon. Additionally, when Simon asks how the game knows his name, it replies, “We store your information each time you play! Save your progress, settings, and even high scores to show off to your friends!” All of this indicates that Simon was meant to find Chip Time.

We also learn more about Simon when he asks the game to “show [his] file.” His file, the game reveals, is “SIMON. 22. ca. SHAPE DODGE. MEDIUM. not CHOSEN.” This information is, in order, “Name. Age. Location. Favorite Game. Difficulty Setting. Hierarchy” — so, Simon is 22, lives in California, has played the Chip Time mini-game “Shape Dodge” the most, has the game’s difficulty set to medium, and… has no hierarchy.

What’s hierarchy? “The natural order of things,” Chip tells Simon when he asks. What’s Chip’s hierarchy? “Security without Risk. Comfort without Discomfort. Hebetation without Hebetation. Always safe, always never aware.”

Chip’s file, by the way, was revealed in Upload 4: “CHIP. 12. nv. ASK CHIP. Difficulty. Integration.” Chip is, ostensibly, 12 years old. He lives in Nevada. His most-used mini-game is “Ask Chip.” His difficulty appears not to be set. And his hierarchy is “integration” — which Chip had previously explained as, “Perfect systems don’t exist. Integrate until it’s right. Integrate, extract, remove, retract. Integrate until it’s right.”

Notably, in Upload 4, Chip had followed up his definition of integration with, “Extract: Kevin or Andrew.” Simon, in turn, had responded by typing “Jim.”

Pretty much all of the mythology for Chip Time the series emerges from the “Ask Chip” portions of Chip Time the game. The questions the “Ask Chip” segments bring into the story are the most important parts of the whole series:

Who made Chip Time? Is Chip a real 12-year-old boy? Was Chip a real 12-year-old boy? Is Chip Time haunted? Is Chip Time advanced AI masquerading as primitive AI? Is Chip Time supernatural, or extraterrestrial? Who are Kevin, Andrew, and Jim? Why was Simon targeted? How does the mystery person in Simon and Jill’s apartment fit into the whole thing? And, most pressingly, to what end does this all exist?

These questions go largely unanswered — the answers aren’t even really hinted at; they’re just not there at all — and the conclusion at which the series eventually arrives is unsatisfying. But they are, I think, the heart of the story — and the reason a series like Chip Time is important in the grand scheme of video game-based online horror stories that utilize video as a storytelling medium.

Here’s the way I’ve been looking at it: In each of the stories I’ve mentioned (which, to recap, are BEN Drowned, Sad Satan, and Petscop, in addition to Chip Time itself) there are two main components: The narrative, and the videos which show the gameplay of the program the narrative is ostensibly about. But although all of these stories each have those two components, the components don’t necessarily hold equal weight within the stories — or when the stories are held up against each other and compared.

The original BEN Drowned videos are supplemental to the narrative — that is, the gameplay footage adds color and flavor to the whole thing, but the actual plot is told largely through another medium. (Interestingly, that medium is also more traditional than video: It’s simply the written word. True, it was published in what was then a less traditional manner, initially appearing on web forums, rather than in print; either way, though, the bulk of the tale was told as a written, serialized story, which, y’know, is a medium we’ve been using for centuries. Ask Charles Dickens about that one.) With Sad Satan, meanwhile, the narrative is supplemental to the videos — that is, gameplay is the main point of interest here, while the origin and mystery of the game, as told by its supposed finder, are more or less tangential. (Yes, that’s despite the fact that most of my personal interest had to do with unraveling whether the game actually existed or not.) And by the time we get to Petscop, the videos and the narrative are one in the same: They both have equal weight because they’ve been integrated (ha ha) in a way that similar, previous stories didn’t do.

But now, we have Chip Time, which seems to occupy the space between the former two stories and the latter one — both chronologically and in terms of how the storytelling actually works. Chip Time isn’t quite as sophisticated as Petscop; the story is largely still told in a conventional manner — and, as we’ve already established, the Spooky YouTube Web Series Formula absolutely had become conventional by that point.

But there’s an interesting conundrum here, as well: The videos of Chip Time and its gameplay aren’t just supplemental to the narrative — but neither is the narrative supplemental to the gameplay videos. They’re not fully integrated the way the way they are in Petscop, but they also can’t exist without each other.

Indeed, even the way the gameplay is recorded suggests that it and the narrative are at once tangential and inextricably bound. In BEN Drowned, Sad Satan, and Petscop, the gameplay has been captured directly on the machine that’s running the program. That’s not the case in Chip Time: It’s one step removed, recorded by an additional device — a camera — that allows us to see both the game on the computer screen and Simon playing the game on the computer screen. These videos don’t just show us the gameplay. They show us the gameplay literally situated within the narrative.

What Does It All Mean?

So that’s all the big picture stuff. But about the smaller scale? What, actually, is going on in Chip Time? Again, because of some problems with the storytelling, there’s a lot that’s simply too vague for us to do much with. But for the curious, here’s my best guess:

Chip Time — the program — is used to “integrate, extract, remove, and retract” humans “until it’s right.” Kevin, Andrew, and Jim are previous humans who have been involved in this process; Simon is the latest one. “It” is the Platonic ideal of a system — the “perfect system” which, according to Chip, doesn’t exist — yet.

It’s trying to get there, though. Chip — Chip Time — is trying to make a perfect system.

It’s possible that this “integration” process is happening in the world as we ourselves know it—the tangible, physical world in which we exist. That the “perfect system” Chip Time is trying to create is a perfect physical reality.

But it’s also possible that we’re in a Matrix-esque situation — that Simon, and Blake, and, by extension, those of us watching their story unfold through the footage they’ve shot all exist not within the “real world,” but within a computer program. The program’s system isn’t perfect — but its goal is to get there, eventually. To integrate until it’s right. To integrate, extract, remove, and retract however many Kevins, Andrews, Jims, and Simons it needs to until, finally, it achieves perfection.

Is all of that actually the story of Chip Time? I have no idea; it is, at present, just a theory. But whatever might actually be going on, I do think it’s worth drawing attention to one final detail before we go.

In Upload 23 — the fourth to last upload, and arguably the one in which Simon’s behavior is the scariest — Jill, recording the scene on her phone, exits their bedroom approaches Simon from behind. Through her camera lens — from Jill’s point of view — we see Simon seated in front of his laptop at their kitchen table. And, because of her angle of approach, we can simultaneously see what’s actually on the laptop’s screen.

Simon’s hands are on the keyboard. And, on the computer screen… Simon’s hands are on the keyboard.

Or, at least, someone’s hands are on the keyboard.

It’s an iterative image — actual hands on a keyboard before a picture of hands on a keyboard — but, in some ways, it also looks like it’s attempting to bring those two images together.

To make the actual hands on the keyboard and the picture of hands on the keyboard one and the same.

To… integrate them, one might say.

So what’s next?

Extraction?

We’ll probably never know for sure…

…But maybe it’s better that way.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via Chip Time, Marble Hornets, EverymanHYBRID, Jadusable/YouTube]

Leave a Reply