Previously: My House Walk-Through.

When I first started the TGIMM feature I’ve hitherto called The Weird Part Of YouTube, I gave the piece that particular name for a few reasons: First, because it was a callback to the title of a thematically relevant creepypasta; and second, because at the time, the Spooky YouTube Video/Web Series style of storytelling was at its height. But this week, at least — and possibly on further occasions in the future — that name requires a change. We’re not talking about a YouTube video or series today; we’re talking about a TikTok account. This particular TikTok account, @FaceTheLight, has been telling a story over the past several months, 30 seconds at a time — a ghost story (or perhaps a demonic one), captured in short videos and doled out bit by bit in a style reminiscent of, but not quite the same as, a good old fashioned YouTube web series.

And that, to me, is quite interesting, indeed.

I’m not on TikTok myself; I am, as they say, An Old, quite far out of the demographic that makes up the bulk of TikTok’s users. (For the curious, about 41 percent of people who use TikTok are between the ages of 16 and 24. I am… not 16 to 24, and haven’t been for a very long time.) But I’ve been keeping on top of some of the bigger trends on the app — particularly trends of the spooky variety (if you’re a Raven Man-tier subscriber to TGIMM’s Patreon campaign, you’ll have seen spooky TikTok videos featured in the newsletter a few times already) — and what I’ve been seeing has gotten me thinking.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

The storytelling in FaceTheLight isn’t particularly sophisticated; there is, in all likelihood, not much more going on than a teenager or young adult making something up on the fly almost solely for kicks. As such, I’m not expecting there to be any sort of deeper mythology connected with the story as — or, perhaps, if — it continues to develop (although if there does turn out to be one, then I will eat my words and happily enjoy what emerges as a delightful surprise). But that’s okay, because I’m not actually interested in figuring out what exactly is stalking the protagonist of the tale. I’m interested in how FaceTheLight fits into the larger picture of found footage storytelling.

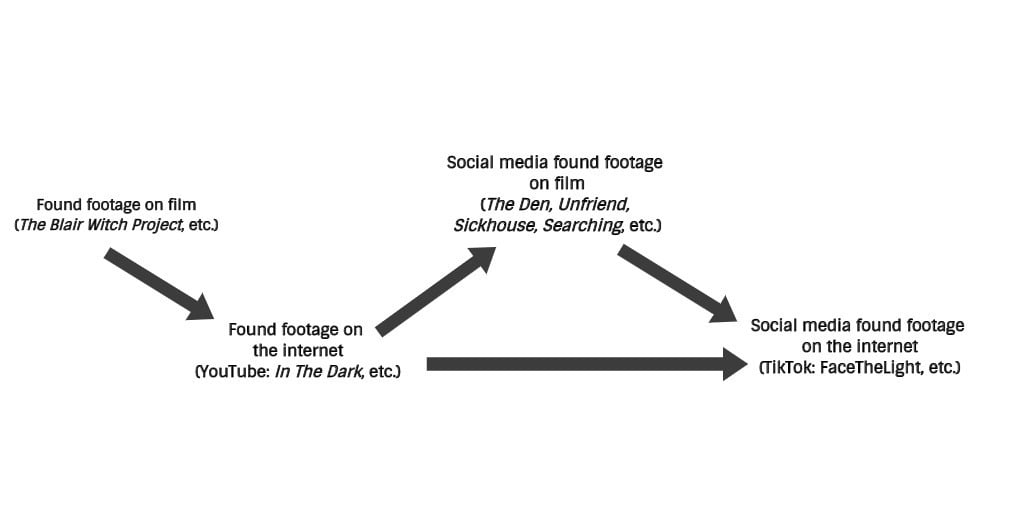

From where I’m sitting, you see, FaceTheLight has a lot of parallels with In The Dark, aka Louise Is Missing, aka the Louise Paxton mystery. And, as I previously established in my piece on that particular web series, the fact that In The Dark occurred in a post-The Blair Project World is essential for its believability — and for the believability of YouTube horror series more generally. So, If In The Dark represents the move from the type of found footage film making seen in The Blair Witch Project to the phenomenon of YouTube-based horror series, then FaceTheLight represents a further evolution in this variety of horror storytelling.

But there’s another stop along the way. We don’t jump directly from The Blair Witch Project to In The Dark, and then from In The Dark to FaceTheLight. Between the Louise Paxton mystery and whatever is going on in FaceTheLight, we actually veer back into film and cinema again. We’re not just retreading old ground, though; this, too, represents an evolution.

Buckle up — we’ve got a lot to talk about.

From Found Footage To Social Media

As a film genre, found footage has been around for a comparatively long time; 1980’s Cannibal Holocaust is usually credited as the first modern found footage film (although, as I noted in my piece on In The Dark, fictional storytelling has made use of blurring the lines of reality for even longer than that), while 1999’s The Blair Witch Project was among the first to fully realize the potential of the found footage framework, thanks to its marketing campaign. But what I’ll refer to as social media found footage films — found footage films which are framed entirely or nearly entirely within social networks, websites, and apps — are a relatively recent invention. After all, at the time The Blair Witch Project premiered, social media itself was still in its infancy; the major players (that is, the ones who have had staying power) were still four to five years away from launching.

The first social media found footage film I remember watching is The Den, which utilized a fictional, Chatroulette-like network — the titular Den — as the medium through which the story was told. The Den was initially released in Russia only in December of 2013 before receiving a theatrical and VOD release in March of 2014 through IFC Midnight.

Not too long after The Den came the first of the Unfriended films, which premiered at the Fantasia Festival in July of 2014 before receiving a theatrical release in April of 2015. Unfriended takes place primarily within Skype, although Facebook also makes brief appearances; overall, the viewing experience is akin to watching a screenshare over a video conference. A sequel, Unfriended: Dark Web, was released in 2018, although story-wise, the two films are unconnected.

Then, in 2016, something new entered the picture: A feature-length film not just designed to look like social media, but one that actually was social media. Sickhouse was both shot entirely on Snapchat and initially released through the app, with its one-to-10-second installments going live between April 29 and May 3, 2016 on star Andrea Russett’s own Snapchat account. At the beginning of June that year, the full film received a VOD release.

Currently, I’d argue that the most successful — and most ambitious — film to come out of this subgenre of found footage is 2018’s Searching. To be fair, I’m not totally sure I’d call this one a social media found footage film; its frame is broader than that: It takes place primarily within David Kim’s (John Cho) computer as he searches for his missing daughter, Margot (Michelle La). Whereas social media found footage can be sort of gimmicky, the frame is essential to how Searching unfolds; it’s an excellent example of how to pull of this kind off this kind of storytelling in a way that’s both powerful and satisfying — and it never gets boring. Not for a moment.

In any event, it’s not odd that social media found footage has really only emerged since the early 2010s, even though social media itself has been around for a bit longer than that. Why isn’t it odd? Because that’s right around the time that most social media apps and networks began to gain video capabilities.

Here’s a quick rundown of which social media platforms and apps launched versus when they achieved video integration:

Facebook launched in 2004 — first solely at Harvard University, then later to a total of 12 colleges and universities in the United States (including my own) — but didn’t receive video capabilities until 2007. It wasn’t until even later — 2015 — that livestreaming became possible on the platform.

Snapchat launched in 2012 as an “ephemeral messaging platform.” Video sharing became part of the platform by the end of the year.

Instagram launched in 2010 and introduced video in 2013. Live video launched on the platform in 2016, along with an Instagram Direct feature that permitted photos and videos to disappear after a certain space of time, a la Snapchat. It’s been owned by Facebook since 2012.

Twitter launched in 2006 and gained rapid popularity in 2007. Video has long been integrated into the platform, but it was with the 2010 version of New Twitter (not to be confused with 2019’s version of New Twitter) that sharing and viewing videos became a key part of the platform — although notably, video-making has never been Twitter’s main focus. When I say “sharing,” I largely mean sharing videos available on other platforms, like YouTube. However, Twitter did also acquire two entirely video-focused platforms not too long after the 2010 update: The company bought Vine in 2012 and Periscope in 2015.

Twitter officially launched Vine in 2013 and Periscope at the end of March, 2015. Vine is probably the closest thing to a direct ancestor that TikTok has; it was a short-form video hosting platform designed to share clips of no more than six or seven seconds. However, Twitter shut it down in 2016. Its archive remained viewable until April of 2019, at which point Twitter discontinued that, as well. Periscope, meanwhile — a service geared towards livestreaming — is still operational now.

Which brings us to TikTok. The original version of the platform, Douyin (抖音), launched in China in 2016; it was then cloned for international markets and launched under the name TikTok in 2017. Parent company ByteDance continues to run and maintain both apps today. (As of this writing, “today” is the summer of 2020.) Both Douyin and TikTok specialize in shortform videos up to 60 seconds in length; they were initially intended primarily to create lipsync videos, but in the years since their debut, their users have found increasingly creative ways to use the apps.

Other relevant dates: Skype, while more of a messaging service than a social media app or network, originally launched in 2003, with the version of the service as we know it now coming along in 2005; it was at its height in terms of number of users around 2013-2014. Chatroulette, meanwhile, was launched in 2009, achieving widespread popularity quickly and falling out of favor just as fast. And then there’s YouTube, of course, which launched in December of 2005 before being acquired by Google in 2006.

I know, I know — that’s a lot of dates. But here’s what I’m getting at: Despite the fact that most of the biggest social media apps and platforms launched between 2004 and 2010, video didn’t become a major part of most of them until the early 2010s. As such, social media found footage could only exist after video arrived on the platforms — and, really, could only exist believably after it had been developed somewhat beyond its initial offering.

And, I would argue, found footage storytelling that’s actually on social media — storytelling that the type seen in like FaceTheLight (with Sickhouse as a stopover in between) — could only exist in a believable form after all of those feature films utilizing social media had come along. We needed the potential to be realized, the possibility to be raised. We needed to shift how we think about social media: We needed to think of it not just as a communication tool used in our everyday lives, but as a storytelling medium in its own right — and one with a new kind of authenticity, at that.

The Haunting Of FaceTheLight

As previously noted, the closest thing we have to a TikTok predecessor, Vine, launched in 2013. A short-form video content platform, Vine allowed its users to create videos of up to six or seven seconds in length, loop them, and share them — which, as you might imagine, lent itself extraordinarily well to the phenomenon of internet virality. Vine’s parent company, Twitter, shut the app down just a few years later, in 2016 — but the void left by it would soon be filled by Douyin and TikTok. Indeed, Douyin launched in China the same year Vine was shuttered and arrived in international markets as TikTok just a year after that. By 2018, it had become the world’s most downloaded app in the Apple App Store; as I previously noted, it’s particularly popular among the 16-to-24 set (hence the term “TikTok teens”).

The creator of FaceTheLight is likely within this 16-to-24 demographic; its protagonist, after all, looks to be no older than college age, possibly younger.

So, with that in mind, let’s talk about what actually happens in FaceTheLight’s videos:

(UPDATE: As of October 2020, FaceTheLight’s account has been set to private and their videos are no longer viewable. However, a full compilation of all the videos can be found here — notably posted by a YouTube channel called simply “Lex,” as in the name of the FaceTheLight’s protagonist’s sister. This channel also hosts a goofy little video uploaded on Feb. 15, 2019 that appears to feature the protagonist of FaceTheLight’s videos.)

The first five videos on the account were all uploaded on Nov. 27, 2019. That doesn’t necessarily mean they were all filmed on Nov. 27 — but regardless as to when they were filmed, they do at least all seem to depict events that occurred on a single night. For what it’s worth, Nov. 27, 2019 was a Wednesday; it was also the day before Thanksgiving in the United States that year.

The first video introduces us to our young protagonist. We don’t know her name, but we learn throughout these first five videos that she has two sisters named Mia and Lex; we also learn in a later video that she lives in California with her family. The family appears to be relatively wealthy and likely based in a suburb; the home, as seen through these first five videos, is large and either a new-ish construction or a well-renovated older one, with a kitchen of which I’m particularly envious: It’s huge, with beautiful counter tops and a double oven.

That kitchen is one of the first things we see. Recording on her phone, our protagonist alternates between selfie-style shots of her face — she’s young and white, with long brown hair and wearing a grey sweatshirt adorned with a small illustration of a mountain range and the word “ALASKA” — and shots of the house’s magnificent-looking kitchen. It’s also here that we learn what, precisely, the situation is: The protagonist and her sisters were “playing hide-and-go-seek in the dark,” she tells us, “and it was my turn to count — but I’m a chicken and I gave up, so I’m just sitting in the kitchen,” she tells us. She shows us the kitchen in question. A dog trots by.

She continues narrating the situation, telling us that one of her sisters has been texting her creepy messages from a spoofed phone number — messages saying that “[Mia and Lex] are gone and there’s someone in the house.” “I know it’s them,” she says, “but I’m just, like, really scared because I don’t like that kind of stuff. Okay, I’m, like — STOP!”

Her shout here is loud and startling — but not as loud and startling as the strange thumping or knocking sound in the background that preceded it. “That’s NOT FUNNY, Mia!” she continues, yelling at someone offscreen. “Get out of here right now. Get in the kitchen! Mia! I’m done.” She turns back to the camera: “I hate this. I hate it. I hate it — STOP!”

The last “STOP” is, as before, spoken to someone offscreen, over her left shoulder. The word turns up into a scream at the end.

The second video documents further knocking and thumping sounds. Our protagonist doesn’t seem frightened anymore — just annoyed at the persistence of a prank carried out by her siblings — but when, in the name of investigation, she approaches a glass door that looks like it might lead to a deck, she makes a frightening discovery:

Crouched before the bottom window is some sort of… creature. It’s humanoid in shape, but not in appearance; its sunken eyes give it look not of a face, but of a skull.

By the third video, our protagonist no longer thinks she’s the victim of a prank. She knows that something else is going on — and she is frightened. “Guys, I don’t think Mia and Lex are here anymore,” she says, recording selfie-style again. “I don’t know what happened to them, if they left — but that was not them at the door I don’t know who it was, but they — all my doors are locked — ”

Another thump, this one louder than the others and sounding more like it’s inside the house than outside of it.

She runs. “Guys, I don’t — ” begins, before breaking off into a scream.

The video cuts out.

In the fourth video, she’s crying. She has made her way into “the elevator,” as she calls it — again, this is clearly a large, wealthy home, although the elevator may also be for accessibility — and shut herself in. “It locks if you don’t press a floor,” she says through her tears. “I don’t know what was running after me,” she sobs, making it clear that, yes, the noise we heard in the previous video indicated that something had entered the house.

She breaks off again as further thumping sounds rattle her surroundings — this time closer than ever: They’re right on the other side of the elevator’s door. She screams, she pleads with it to stop, she asks who it is (although perhaps what it is might be the better question)—and, she notes, speaking to the camera, that in case there was any doubt about why she’s still recording, it’s “in case something happens” to her — that is, she believes she might very well be documenting her last moments.

She’s calmer in the fifth video; although she’s currently still trapped in the elevator, she’s come up with a plan. “I’m deciding to go to the basement,” she says. “There’s a back door that I can run out of and hopefully… run to something.” She doesn’t know what exactly is in the house with her—but she knows that something is in the house, and that’s not one of her sisters.

The lights inside the elevator flicker as she slides open the accordion-style door. There’s a second door behind it — the kind of interior door that’s prevalent in newer suburban homes, painted white and fitted with a silver-toned handle rather than a knob. She cracks this second door open and steps out cautiously, the camera focused on the cream-colored, carpeted floor.

Almost immediately, something growls. She screams, yelling at the thing to get away from her. It tackles her, and the camera tumbles to the ground as she continues screaming.

And that’s where the first five videos end.

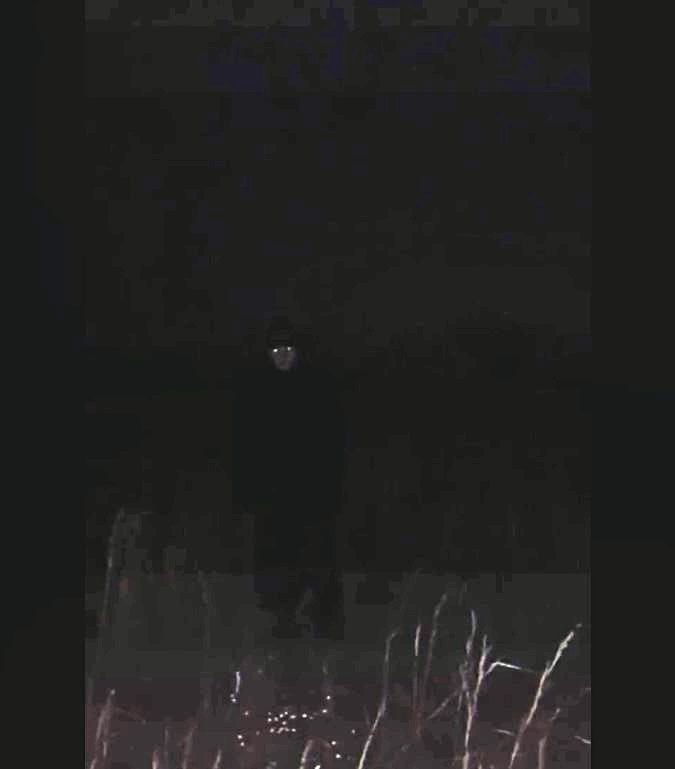

The sixth video was posted the next day, on Nov. 28 (again, that’s Thanksgiving in the U.S., for anyone keeping track). It shows our narrator in a dark room, hands bound, face bloody, and crying. Something inhuman growls loudly nearby; indeed, the growls are loud enough that it’s possible whatever responsible for the noises is actually holding the camera. Then, on Dec. 8 — a week and a half later — a seventh video arrives. This time, she is no longer in the dark room; she’s outside, somewhere with long grass — a field, perhaps. From her crying, it sounds as if she’s the one behind the camera again. It’s pitch-black, but there seems to be something standing in front of her in the darkness:

As before, it’s humanoid in shape, but not necessarily in appearance. All we can see is the outline of a bipedal creature, a splash of darkness where its body is, and two glowing spots where its eyes should be.

For the curious, here’s a brightened-up version of the previous image:

And then, nothing — until March 29. (By this point, most states in the country had issued extended stay-at-home orders or would do so within the next week.) And when this batch of videos arrived, they presented quite a departure from the previous videos: First, while the original videos (or at least, the first five) were generally addressed to “you guys” — meaning our protagonist was likely filming and posting them specifically for a broad social media audience — the next three are addressed to her mother. They have a more intimate feel to them — and yet, at the same time, they’re initially somehow more performative.

There have also been a lot of changes to our protagonist’s life in the intervening months. “I know I said I’d send you more videos, so here I am,” she says in the first one. “I miss you guys! I miss California, but Ohio’s good, I guess? Kinda boring.” And there, we finally find out both where the original videos had been recorded and where she is now: She’s from California, but has now relocated to Ohio. She lives with someone else — either a partner or a roommate — named Eli, but because “Eli’s working really late tonight,” she’s alone in her new home right now. As she walks the camera around her home, she shows her family what she’s been keeping busy with: A puzzle, which looks to depict a collage of book covers; getting her room set up; getting used to her new kitchen; and more.

But it quickly becomes apparent that all is not well.

At the end of the first video, a loud, familiar thumping sound. She looks up and away from the camera for a moment; then, when she turns back, she says, “Um, mom, I’ve gotta go. Love you, bye.”

In the second video, filmed in her bedroom, she apologizes for cutting the previous video short; she says she isn’t sure what the sound was, but that she thinks maybe a book fell off her shelf. She starts showing her mom around her room, but another loud noise — offscreen, but nearby — causes her to jump.

In the third video, she’s in the kitchen — a very different kitchen from the one seen in the November videos. Here, she gets more explicit about the situation: “Hey, Mom, as you probably saw in the last video, some really weird stuff has been happening around here,” she says. “Like, I keep hearing, like… random noises.” She goes on to say that she doesn’t want to freak her mom out, and that she herself isn’t “that worried about it,” even though she also admits that “it’s kind of freaky” — but she carries on, showing off her kitchen… until the lights begin flickering.

In the fourth video, the lights have gone out and the camera is trained at her bare feet. She sounds tearful: “Mom, the power went out, I don’t want to freak you out anymore, but…” She cries softly for a few seconds. “I think… I think it’s back,” she says.

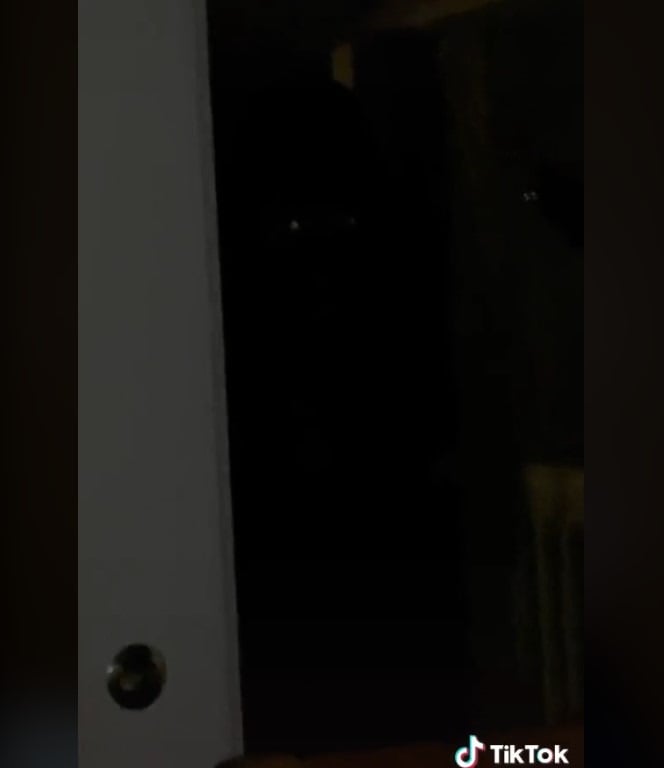

And then she realizes there’s something on the back porch:

Editing the image doesn’t reveal much else — we can’t see the outline of the figure this time — but the eyes are clearly the same ones from the seventh video of the original batch.

In the second last video, our protagonist creeps around the house in the dark, crying, the camera pointed away from her while knocking and thumping noises fill the space around her. She zooms in on a window, and the glowing eyes are there, now, too.

And in the final video, she runs — she runs through her home and shuts herself in a closet. She’s trying to hide, but the thumping noises on the other side of the closet door indicate that she has failed to hide sufficiently.

The door slides open.

A figure with glowing eyes approaches.

She screams.

And right now — that’s where the story ends. We don’t let know whether more is on the way or whether this is the ultimately conclusion, but it’s what we have to work with for now.

Honestly, though, it’s plenty — especially if you’re interested in holding it up against one of its predecessors.

You see, I don’t think FaceTheLight is notably solely for its position in the film à internet à film à internet progression of social media found footage storytelling I’ve already laid out. It’s also notable when compared with In The Dark — because I actually think that the film à internet, etc. diagram actually looks more like this:

From Louise Paxton To FaceTheLight

I’m not sure the creator behind the FaceTheLight channel knows about In The Dark; in fact, I’d be willing to bet that they don’t — partially because In The Dark is relatively obscure, as far as web series go, and partially because they would have been very, very young when it was originally made. (Assuming that FaceTheLight’s creator is around late high school or early college age, they’re probably somewhere in the neighborhood of 18 to 20, give or take a few years. Given that In The Dark was uploaded in 2007, they would have been around five to seven years old at the time — not exactly the series’ target audience.) But at the same time, there’s a lot about FaceTheLight’s story that reminds me of In The Dark — and, in some ways, it represents a sort of evolution in this kind of storytelling.

The world moves much faster now than it did in 2007. The internet in particular moves faster. Content is much more likely to be encountered in smaller, more easily digestible bits.

And with all of this in mind, FaceTheLight is almost like what might happen if you took In The Dark and squashed it down a bit: It tells a very similar story, but the economy of storytelling that arises from shifting the medium from YouTube to TikTok means that it all happens much, much quicker.

First, there’s the simple matter of the length of the videos: Although YouTube in 2007 was much more limited in terms of how long a single video could be, Louise’s are all still at least several minutes apiece; the longest runs nearly eight and a half minutes. (In that sense, it’s not too dissimilar from Snapchat, which also allows for the creation and sharing of video clips up to a minute long. See also: Sickhouse, the 2016 Snapchat-shot horror film.) FaceTheLight, however, is even more limited, due to TikTok’s maximum video length of 60 seconds. All of FaceTheLight’s videos are even less than that, though; at their longest, they’re around 35 to 37 seconds in length.

But then there are the overarching timelines for each story, as well.

In The Dark takes place over about three months in 2007, starting in early April and continuing through the beginning of July. The first five videos, which cover most of April, are low-octane; they’re just everyday vlogs, introducing us to Louise and her initial circumstances. The rest of the videos, however — about 25 of them, covering the very end of April until the end of the story on July 4 — are considerably more action-packed. But even here, there are ebbs and flows: Four videos between the middle and end of May show less activity, for example, while the 10 or so before them are more intense. What’s more, the 10 videos after that calmer set of four ramp up the situation considerably until we reach the showstopper on which the series concludes.

The full story (so far) of FaceTheLight also takes place over many months: Currently, it spans about four total, running from the end of November to the end of March. There are only 13 videos — many fewer than In The Dark — but they follow a similar pattern, ebbing and flowing in intensity: The first two videos are relatively tame, while the third through eight videos escalate rapidly. Then, the first two videos of the second batch — the ones that take place in March — dial things back a notch again before kicking it all up once more for the third, fourth, and fifth videos.

But although FaceTheLight’s story is technically spread out over several months, the action itself takes place over a much shorter amount of time. Effectively, the story is told over no more than four days, with the bulk of the action occurring on just two of those days. To me, this demonstrates an evolution in form: What was told via YouTube over several months in 2007 is told via TikTok over just a few days in 2020.

The second batch of FaceTheLight’s videos also strikes me as very In The Dark-like in a specific way: Its audience. Whereas the first batch of videos was clearly intended for a social media audience — that is, the viewers included some friends, probably, but also lots of strangers — the March videos are more intimate. They’re intended for a personal audience: The protagonist’s family, specifically her mother. Similarly, most of Louise Paxton’s videos were filmed for her friends and family, rather than the internet as a whole; they only became accessible to a social media-style audience by dint of the fact that YouTube didn’t have a private or unlisted video feature in 2007. (The exceptions are the videos she makes to document what she believes is a stalker to bring to local law enforcement.)

In some ways, this might be seen as FaceTheLight inverting In The Dark’s audience intention; in others, though, it might be seen, again, as a sort of evolution: In 2007, many of us used the internet mostly to communicate with people we already knew; if strangers came into our online spheres, it was coincidental at best. That’s why Louise assumes her videos are only being seen by her friends and family, rather than a lot of randos on the internet. In 2020, however, I’d go so far as to say that the internet is used primarily to communicate with people we don’t know in “real life,” so the fact that FaceTheLight starts out with a broad audience of randos and then scales down to family seems… meaningful.

And then there’s the matter of how the audience fits into the timeline of the story, too. Although I did note that just because FaceTheLight’s videos were all posted on specific dates doesn’t necessarily mean they were filmed on those dates. I do think the takeaway we’re meant to have is that they were filmed and posted at roughly the same time. And the reason I’m of this mind is due to the fact that bringing found footage storytelling back from film to the internet via social media makes the storytelling, by nature, much more immediate.

When you’re watching a found footage feature film, there’s often a need to justify how the footage itself actual got in front of the audience watching it — hence “found footage” as a term: The understanding is that someone — probably someone unconnected with the creation of the footage — literally found the footage, spliced it together, and made it available to the people currently watching it in some way, shape, or form. Regardless as to whether this understanding is made explicit, such as through a title card or piece of opening narration, or kept implicit, the audience is a step or two removed from the action seen in the footage itself — that is, if someone found the footage and made it available for us after the fact, we cannot, by definition, be watching the action depicted in it unfold in real time.

This is also true of YouTube: The platform isn’t really designed for immediate posting — or at least, it’s not really at its best if you simply shoot a video and upload it immediately. With something like FaceTheLight, though — and, to some extent, something like Unfriended or Searching, depending on how you watch it (it’s a very different experience to watch these films on an actual computer, versus on a television or in a cinema) — we can experience the story in real time. Although it’s true that tons of editing often goes into social media posts, the apps themselves are built for immediate ease and access: You can write a status, take a photo, or record a video on your phone, and then post it to the platform of your choice immediately.

Again: The evolution of a form. Film audiences watch found footage films long after the footage was filmed. YouTube audiences can watch the footage sooner, and they can watch everything unfold as a serialized piece of storytelling, but unless they’re watching a livestream — which wasn’t an option when In The Dark was made — they’re still always watching it later than when the events themselves occurred. Social media found footage on film blurs this line a bit — but then social media found footage posted on actual social media positions both the characters and the audience as existing within the same timeframe.

The Future Of Found Footage

This — all of this — is one of the reasons I haven’t gotten sick of found footage horror yet: Filmmakers and storytellers keep finding new ways to present it. Sure, when found footage is done lazily, it’s boring; but as the makers of all of the works we’ve talked about in this behemoth of a piece have demonstrated, as long as you keep building off of what came before you instead of merely recreating it, there are infinite possibilities. Not all of them will work, of course — but sometimes, it’s not whether it works or not that matters. It’s that you took the risk to try at all.

Will there be more FaceTheLight in the future? Unknown. It’s actually a relatively complete story as it is; although there’s absolutely room for more, it does have a pretty sold plot: Demon/ghost targets girl; girl escapes demon/ghost; girl thinks she’s safe from demon/ghost; demon/ghost finds girl again; demon/ghost gets girl; the end. I wouldn’t be mad if it stopped there.

But I do hope it keeps growing. I hope it surprises me. And I hope others keep thinking outside the box in the same way this particular account is, too.

That’s what makes it all so much fun.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via antonbe (remixed by Lucia Peters), ataioli, StockSnap (remixed by Lucia Peters)/Pixabay; Jeff Carter/Flickr (available under a CC BY 2.0 Creative Commons license); Eric Mclean/Unsplash; FaceTheLight/TikTok (4, remixed by Lucia Peters); diagram by The Ghost In My Machine; In The Dark/YouTube.]

Leave a Reply