Previously: Blank Room Soup.

On Oct. 16, 2016, a video tour of a house in Japan arrived on YouTube. This, in and of itself, is unremarkable; lots of video tours of houses, in Japan and elsewhere, exist on YouTube. But, when it appeared, the video “My house walk-through” was… different than most house tour videos. It was weirder. Creepier. More unsettling, despite the fact that its description stated that it was “not a horror video.” But if one were to watch it closely — to stick with it throughout its entire running time — it would become apparent that “My house walk-through” was a horror video. A story would emerge — and the story of “My house walk-through,” it turns out, is nothing short of a ghost story.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available for purchase now!]

Or at least, it’s a ghost story as I view it. It’s not straightforward in its narrative; indeed, one must decode the video in order to get anything other than a creeping sense of dread out of it. But if you look deep enough, the story is rich, and full, and tragic — the story of a house full of ghosts, and what happened to them to cause the haunting.

Of course, the fact that “My house walk-through” is spooky as heck isn’t a surprise to anyone who looks at the name of the YouTube channel on which it’s hosted: It was uploaded by user nana825763, otherwise known as the Japanese visual artist, animator, and experimental filmmaker PiroPito. As such, “My house walk-through” doesn’t require debunking or an attempt to determine whether it’s real; it’s not — it’s expressly a work of art. PiroPito doesn’t even keep how he put the video together a secret: A few months after the release of “My house walk-through,” he posted a making-of video documenting the creation of the project from start to finish. (Update, August 2021: Apparently the house in which PiroPito made the video has been demolished. He took one last walk around the place to document it before the demolition crew came in; you can watch that video here.)

So, debunking isn’t what I’m interested in here. I’m interested in working within the world established by the video to figure out what, precisely, its story is.

Let’s take a crack at it, shall we?

This Is Not A Horror Video

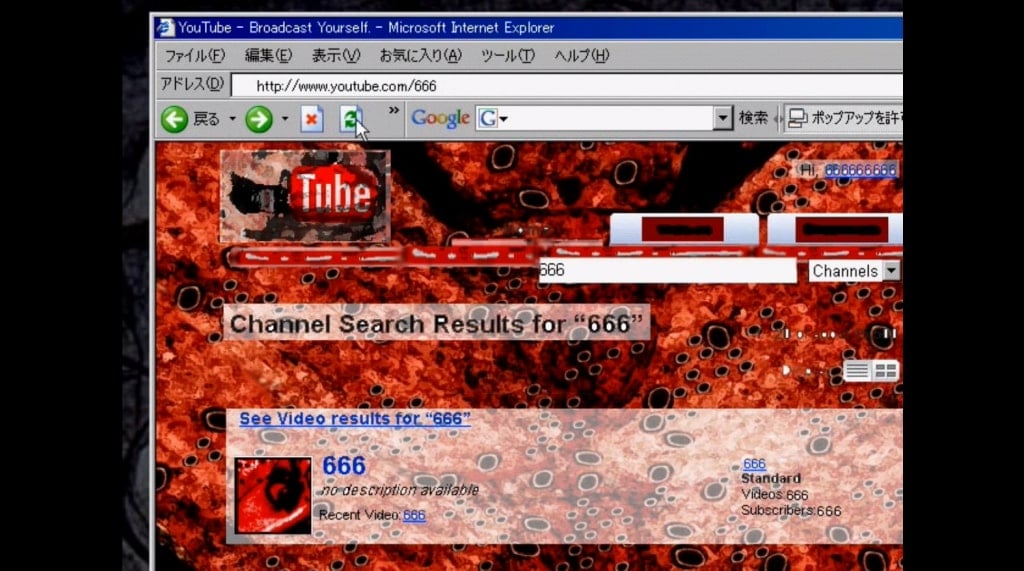

PiroPito is probably best known for the video “Username:666” — or, in its original form, “SM666.” First posted to the Japanese video-sharing site niconico (then called Nico Nico Douga) under the “SM666” name in March of 2007, it made its way to YouTube with the English language title for which it would eventually become widely known on Feb. 26, 2008. (The original niconico video had been deleted by early 2008, although it had been re-uploaded by another user at the very end of 2007.) Best described as a creepypasta in video form, “Username:666” showed what allegedly happens if you search for a user on YouTube going by the name “666” — a user who doesn’t exist. However, the video suggested that if you manually input the URL that would take you to user 666’s channel if it existed, then refresh the page a number of times, you’d experience… something untoward. Once the video hit YouTube, where it was posted by the channel nana825763, it took on a life of its own; a number of English speakers retroactively put together a written story to go along with it, although the written story — nor its many drafts — isn’t actually part of the original lore.

Eventually, folks figured out that the YouTube channel nana825763 belonged to Japanese artist PiroPito. Not much is known about PiroPito; he’s never made much information about himself public. He’s never even revealed his face online — or at least, not his face as it appears now. He regularly uses a photograph of a small child as his profile image, although whether this photograph is actually of PiroPito in his childhood or not remains to be seen. He apparently lives in Kanagawa Prefecture, which is south of Tokyo; he’s been self-producing his own videos since 2000; those videos are occasionally screened at film festivals in Asia and Europe; and… that’s really about it.

For a time, PiroPito did have a website; however, it was hosted at Geocities, which was discontinued in its final form as a product of Yahoo! in March of 2019. You can access PiroPito’s website through the Wayback Machine, of course — but between the imperfect manner in which Google Translate handles Japanese and the clunkiness inherent in sites made with Geocities, it’s a challenge for English speakers to navigate. It does at least give us a window into PiroPito’s work — you can see a list of his pieces here which range from animated GIFs to full videos — which is fairly easy to parse, though, so at least there’s that.

But just because PiroPito doesn’t talk a lot about himself biographically speaking doesn’t mean he’s uncommunicative. On the contrary; he actually engages with the public quite a bit. His Geocities site featured a diary section where he wrote frequently about what was he working on, as well as chatting about the more mundane aspects of day-to-day life. He’s also been quite active on Twitter since 2009, which is where most of his regular updates occur at the present.

What I like so much about PiroPito’s work is that it’s often incredibly story-driven, but not necessarily plot-driven. And because it’s not plot-driven — because it doesn’t spell everything out, step by step — it challenges viewers to determine what the story of any given piece actually is.

So here’s an idea of what might be going on in “My house walk-through.”

Tonight, I Want To Introduce My House

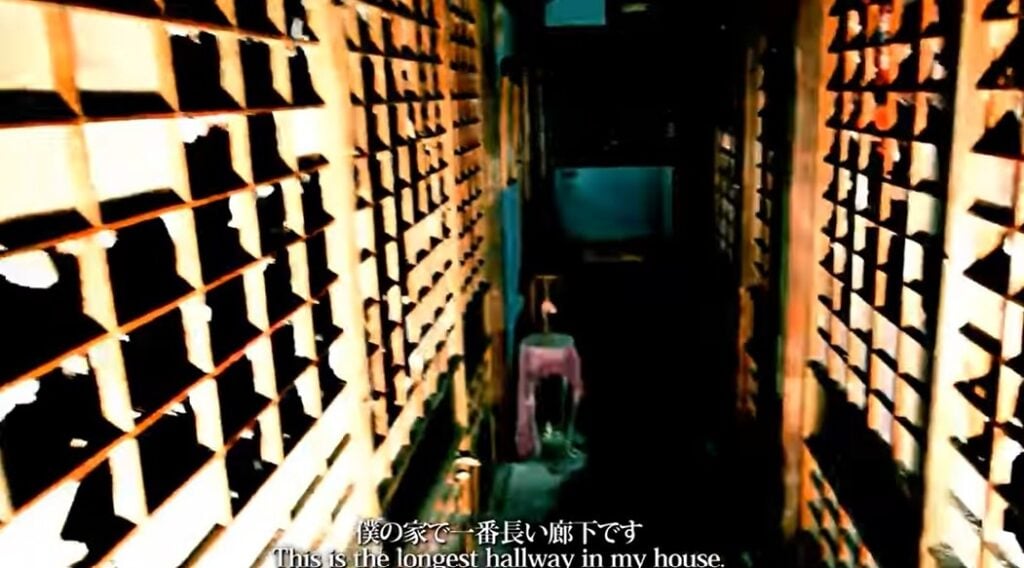

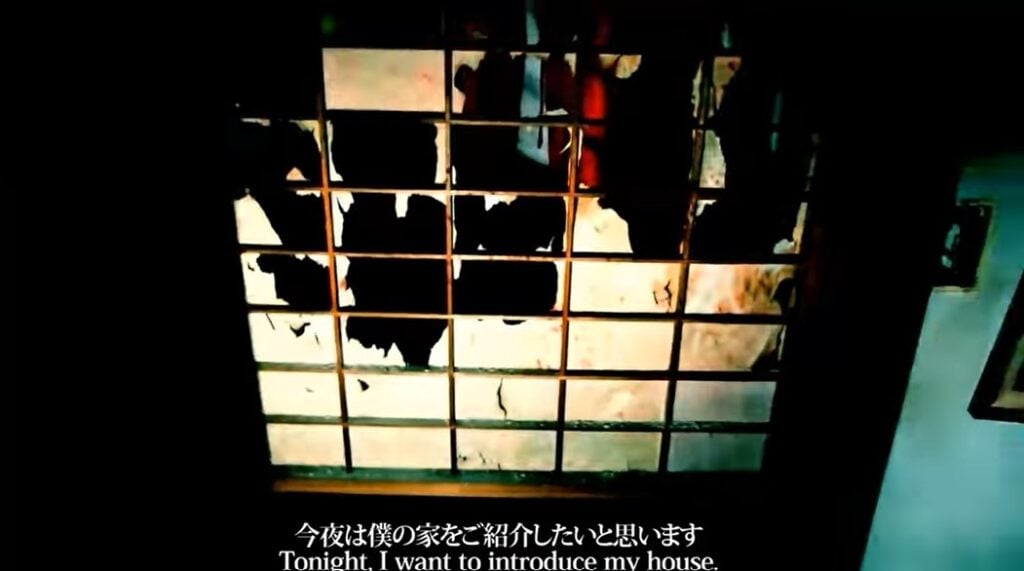

“My house walk-through” is fairly long by PiroPito’s standards; most of his videos clock in at around two or three minutes, but this one is 12. Shot from a first-person perspective, it takes the form of — as the title might suggest — a walk-through of someone’s house. It’s a traditional Japanese house, with tatami mats, shoji walls, and sliding fusuma doors throughout. An altar and a handful of photographs and portraits make homage to the homeowner’s ancestors.

But all is not well here, in this house, this dark, damp abode — a very un-home-like home. Like most of PiroPito’s videos, “My house walk-through” burns slowly. There are no jumpscares; no monsters; no ghosts or yokai or onryo; just… a house. A house behaving as a house should not, and becoming more and more decrepit over time.

We start in a bedroom.

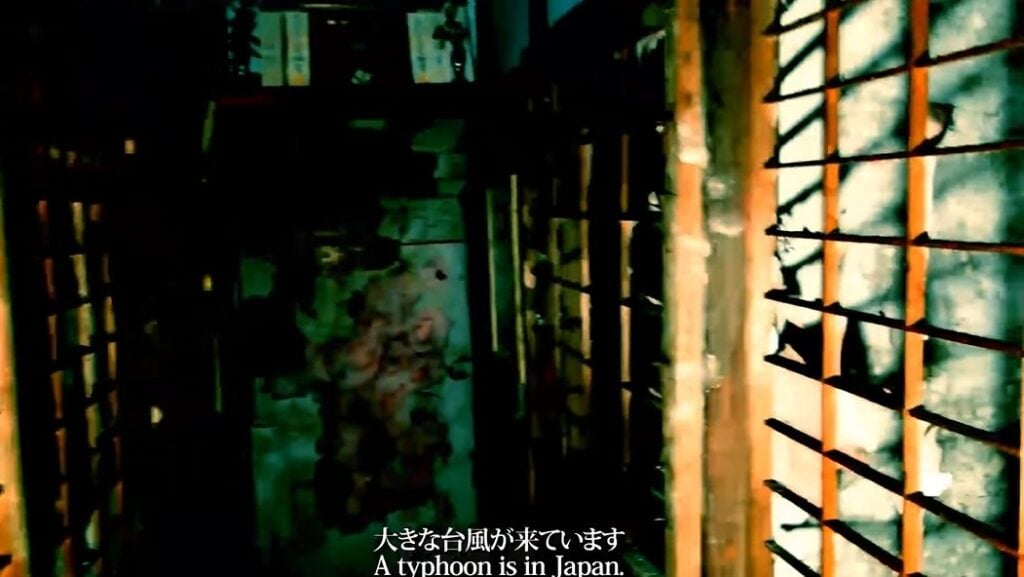

“The sound of the wind woke me up in the middle of the night,” the narrator of this strange house tour tells us — not through speech, but through subtitles. There is no spoken language featured at any point in the video; we find out about the various rooms of the house only through written text. “A typhoon is in Japan,” the narrator says. It sounds like an explanation — the reason the house appears dark and a little bit damp, the reason the narrator is up at this hour.

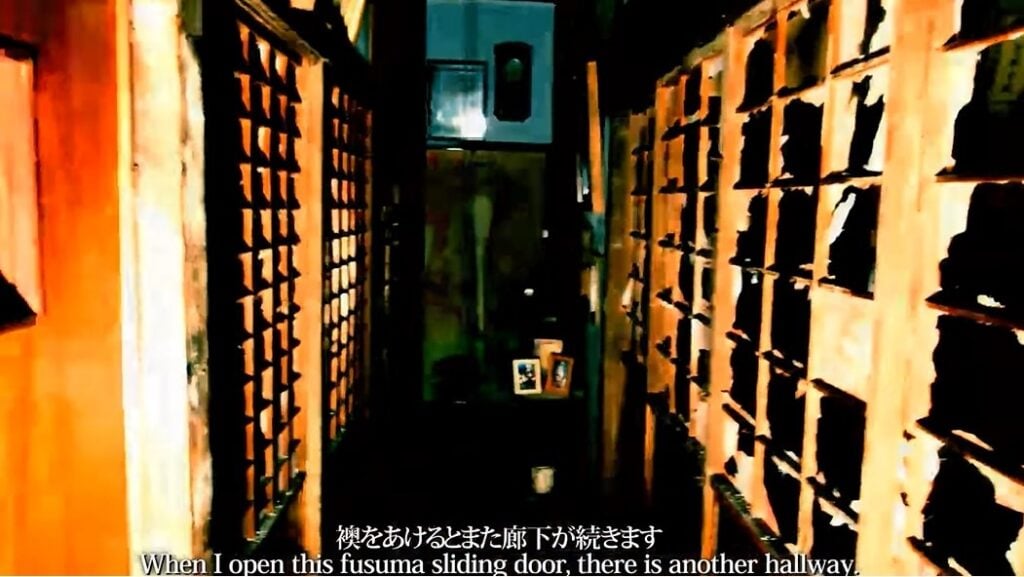

They begin to take us on a tour of their home: We see their bedroom, where “the tatami mats are terribly damaged”; the “longest hallway” in the house; the “Hina Doll room”; an altar and portraits of ancestors, at least one of which our narrator tells us is “from around the time of WWII”; a fusuma sliding door, behind which lies another hallway; a “doll room” — not to be confused with the Hina Doll room — which “was closed up by my grandfather”; more photographs and portraits, this time of the narrators mother when she was a child and the narrator’s great grandmother; another hallway, seen after turning left at the end of the first hallway; and bathroom.

“I hear a sutra,” the narrator says — a sutra being a religious text. In Japan, it would be a Buddhist one. “My grandfather is always listening to sutra from the radio,” they say; the way they describe sounds similar to hearing a sermon play from an evangelical radio station.

“The wall peels off from the ceiling when it rains,” they say, tilting the camera up to show us. Then: “This is the longest hallway in my house”— a repetition of something we’ve already heard. And: “A typhoon is in Japan” — another repetition. And: “This is my room.” And: “The tatami mats are terribly damaged.”

And: “When I open this fusuma sliding door, there is another hallway.”

You may not notice it at first, but quickly, you begin to realize that behind that fusuma sliding door is a hallway that looks… familiar. One that we may have already seen. But how? We’ve gone through a fusuma sliding door, traveled down one hallway, turned left, and gone down another before moving through another fusuma sliding door. That’s an L-shape — not a long enough circuit to have come back where we began, if we assume the house to have an interconnected, square-shaped layout.

And yet, here we are: Back at the narrator’s room.

Back at the start.

Back where we shouldn’t be — not quite yet.

We make a second circuit of the house. During this circuit, we hear again about the picture from WWII, the hallway seen after turning left at the end of the previous one, and the longest hallway in the house; new, however, are views of a “dress room” and the narrator’s grandmother’s bedroom. We don’t go into either room — in fact, we haven’t been into any rooms so far, other than the one we started out in — but the narrator tells us that both rooms were closed up by their grandfather.

We arrive at the end of the hallway. “When I open this fusuma sliding door,” the narrator says, “there is another hallway.”

And there is — but it’s the same hallway.

All told, we make eight circuits throughout the house — this impossible house, this house with hallways folding back on itself

During each circuit, we view new rooms, and sometimes go into rooms we’ve seen before, but haven’t entered.

We go into the bathroom, where “the ceiling has rotted and fallen away” and where “there are rats’ nests above the ceiling.” We go into the dress room, where there lots of dresses belonging to the narrator’s grandmother, all with “holes eaten by insects” which have “turned black like bloodstains.” “My grandmother is not here,” the narrator says.

We go inside the doll room. The dolls have been there for decades.

We go into the Hina Doll room. “No one has been in this room for a very long time,” the narrator says.

During each circuit, the repetitions of phrases we’ve already heard grown more frequent — and also, the house begins to… change. It gets wetter. More damp. Sections of it seem to be covered with living tissue. Red appears — smeared on walls, overflowing on floors, tinting the world in raw, bloody shades.

The new circuit always begins after the narrator slides open the fusuma door.

We go into the narrator’s grandmother’s bedroom. We go into the bathroom again.

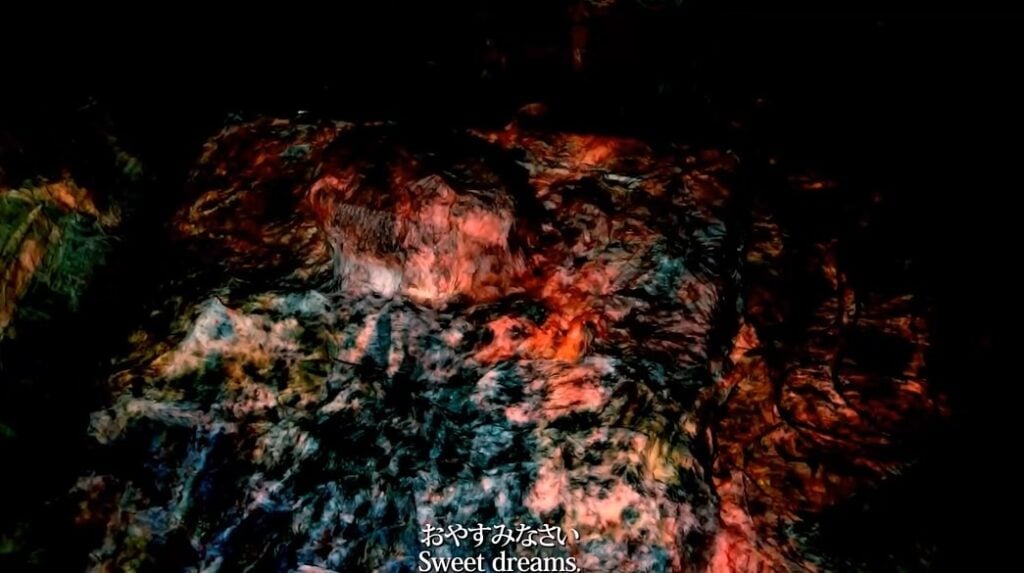

In grandmother’s bedroom, the narrator tells us, someone is actually present: “Grandmother is here,” they say.

On the bed, there’s a human form, mummified in the same, tissue-like material we’ve seen begin to creep over the edges of the house.

In the bathroom, there is now a doll in the sink. There is now red water on the floor.

There is now someone in the bathtub.

“Grandfather is here,” says the narrator.

In the bathtub, soaking in water stained the color of blood, is another human figure

The next trip through the fusuma door reveals the house to have been overtaken entirely by the tissue-like substance.

“The sound of the wind woke me up,” the narrator tells us.

“A typhoon is in Japan,” they remind us.

“The ceiling has rotted and fallen away,” the say. “There are rats’ nests above the ceiling. The holes eaten by insect have turned black, like bloodstains.”

“No one has been in this room for a very long time.”

We end, finally, back in the narrator’s room.

“This is my room,” they say.

“A typhoon is in Japan,” they say.

And, lastly, just before the video blacks out: “Sweet dreams.”

A Typhoon Is In Japan

For a video that doesn’t expressly tell us a whole lot about itself, there are actually quite a lot of details about the situation we can glean from it anyway. First, we’re somewhere old: The architecture is traditional, and the house has likely been in the family for several generations. Second, it’s raining. And third, we’re at least few years removed from the Second World War. These details frequently emerge in the repetitions seen in the subtitles — references are made time and time again to the narrator’s grandparents, for example, as are comments that “the walls peel away from the ceiling when it rains” and that one particular portrait dates back to World War II. But what I would argue is the most important detail is spoken only four times — twice during the first circuit, and twice during the last: “A typhoon is in Japan.”

As an island nation in the Northwest Pacific Ocean, Japan is prone to typhoons. The term is actually one of several terms used regionally to refer to tropical cyclones; in the Northwest Pacific, the term “typhoon” is in use, but in the North Atlantic, central North Pacific, and eastern North Pacific, they’re called hurricanes. In the South Pacific and Indian Ocean, they’re just called tropical cyclones. No matter what you call them, though, they consist of “rotating, organized systems of clouds and thunderstorms that originate over tropical or subtropical waters” with “closed, low-level circulation,” per the National Ocean Service. They form when warm, moist air from the ocean rises while colder air moves in below, creating pressure and leading to quickly rotating winds. When the winds reach about 61 kilometers per hour (about 39 miles per hour), the systems are classified as tropical depressions, but when they reach 118 to 156 kilometers per hour (about 74 miles per hour or higher), they’re officially typhoons.

Typhoon season in Japan typically runs from around May to October, but the peak months are August and September — and in 1959, September brought with it one of the most destructive typhoons on record. Referred to as Typhoon Vera, the Isewan Typhoon, and T5915, the storm system hit the Ise Bay region of Honshu on Sept. 26, absolutely devastating the nation.

Remember how storm systems are officially typhoons when they reach 118 kilometers per hour/74 miles per hour or higher? Well, when they reach about 240 kilometers/150 miles per hour, they’re called super typhoons.

The winds of the Isewan Typhoon reached 306 kilometers, or about 190 miles, per hour.

5,000 people were killed during the storm. Nearly 39,000 went missing. More than 1.5 million were made homeless. The total cost of damages ranged between 500 and 600 billion yen, which at the time was equivalent to about $261 million USD, but adds up to nearly $2.3 billion in today’s money — this, in an economy already in shambles following the end of the Second World War. It’s true that Isewan led to wide-scale disaster and emergency management reform; however, the cost of that reform, literally and figuratively, was enormous.

Japan is still frequently beset by typhoons today; that hasn’t gotten any better (and, indeed, thanks to climate change, will probably end up continuing to get worse). Just this past October, Typhoon Hagibis struck the Kanto region, killing at least 90 people; it also triggered both a tornado and an earthquake, adding to the destruction and chaos.

With this as our backdrop, the details of the video — the commentary on the rain, the increasing dampness of the house’s interior, the repeated note that there’s a typhoon in Japan — begin to take on a more distinct shape. They take on the shape of a story — a story of a family who stays at home as a storm approaches. The story of a grandmother, a grandfather, and a grandchild who do not evacuate — or, perhaps, who do not get the chance to evacuate — as the storm becomes worse. The story of a family who become trapped in their home as the storm grows in strength, transforming from mere rainfall first into a tropical depression, then into a full-blown typhoon.

The story of a family who dies in that typhoon — drowned, perhaps, or crushed as sections of their home’s roof collapses, or both.

The story of a family who is still stuck there, in their home, in the place they died, cycling through and through and through their final night on loop, replaying the memory that no one holds but themselves.

The story of a family of ghosts.

The story of a haunted house.

The connection to World War II also strikes me as interesting. Again, the house tour seen in “My house walk-through” occurs sometime after the war: The narrator points out several times that one portrait on the wall is “from around the time of WWII.” And we know that one of the reasons the Isewan Typhoon was so difficult to recover from was because Japan’s economy was already a mess from World War II.

So: What if the occupants of the house didn’t die in just any typhoon, but specifically in the Isewan Typhoon?

It’s worth noting here that there seems to be a generational gap at work within the family who occupies the house — one which may be relevant in terms of placing the house’s story within some sort of historical context: We know the narrator, their grandmother, and their grandfather live there, but although we do see a photograph of the narrator’s mother as a child, we hear nothing of her as an adult; there’s no indication that she lives in the house with the grandparents and her child — nor, for that matter, any indication that she’s even alive. The narrator’s father, too, is absent; he isn’t mentioned at all.

At least 123,000 children in Japan were orphaned during the Second World War — and likely even more than just that: The Japanese government ignored the “war orphan situation,” as it’s been termed, for several years; the figure we have is just what they were able to count by the time they finally got around to investigating the situation in 1948. It’s not out of the realm of possibility that the narrator could have been one of these orphaned children, taken in by their grandparents following the death or disappearance of their parents — who then, as a young adult, perished along with their grandparents when Isewan struck Japan in 1959.

Sweet Dreams

Could the typhoon depicted in the “My house walk-through video” be a more recent typhoon? Of course. Would it make more sense if it was a more recent typhoon? Perhaps; it is, after all, unlikely that a family living in Japan in 1959 would have access to the kind of camera required to record this quality of footage — not to mention the fact that YouTube specifically and the internet more generally obviously weren’t around at the time. There’s also the question of how and why a ghost would record this video nearly 60 years after the face, and post it online, and, and, and…

…There are numerous reasons why this theory may not pan out. But at the same time, I also think it’s one of those situations where thinking about what might be going on, but not overthinking it, is key. Everything detailed here is the story that I, myself, take away from the video. It might be different from the story you take away from it — and, most importantly, your version, my version, and any other version of the story anyone might come up with can absolutely be the “truth” of the piece depending on who’s viewing it.

For what it’s worth, I think PiroPito would approve of this particular standpoint. As he told YouTuber ReignBot in 2017, he purposefully “avoids giving his artwork any solid meaning or purpose” and “chooses to embrace chaos and nonsense” — which, in turn, means that any interpretation of his work, no matter how outlandish, is valid for whoever believes it.

As for what PiroPito himself has been up to lately? Well, mainly… playing Minecraft. Yes, really. Since the summer of 2017, he’s been making and uploading short vides of his very first Minecraft playthrough — but he’s doing it in a way that only PiroPito could: He’s made a point of keeping himself isolated from any and all knowledge of what Minecraft is, how it works, what the lore might be, and how you might strategize playing it — that is, it’s a completely cold playthrough, and it is delightful.

Does part of me hope that his Minecraft project is all part of some massively long con that will, like so much of his other work, pay off in some beautifully creepy fashion later on down the line? Yes. Is that likely to be the case? Probably not. But honestly, it’s still as enjoyable as everything else PiroPito has created, even without the spookiness and uncanniness. You can watch it all here, if you like; just, y’know, watch out for those Creepers.

Oh, and make sure you keep an eye on the weather report.

Head to high ground if necessary.

Don’t forget your umbrella.

And stay dry.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via nana825763/YouTube (4)]