Previously: ‘In The Dark’ & The Louise Paxton Mystery.

Have you ever woken up one day and felt that your surroundings… weren’t quite right? They may have looked the same as always — but something about them seemed… different. Bad. Wrong. For a young woman known only as Mary, that’s what every day is like — but when it comes to what the web series Hi I’m Mary Mary is really about, there’s much, much more at play than just a feeling that something is off. Everything is off — and if she’s not careful, it could end up costing her life.

I’m not always a big proponent of Freud, but there is one concept of his that I keep coming back to again and again: That of the uncanny. In his 1919 essay on the subject, (called, fittingly, “The Uncanny”) Freud defines the uncanny as “that class of the terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar” — that is, what makes something feel uncanny to us is when we’re familiar with it, but it’s been twisted in some way, shape or form. Something that’s uncanny often retains its original appearance (or something close to it, at least); however, it no longer feels right. It feels wrong. It is, in short, something familiar that’s been made strange.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

Hi I’m Mary Mary is awash with the uncanny — and ultimately, that’s also what reveals what the whole story is actually about.

“Hello, My Name Is Mary”

Mary uploaded her first video to YouTube on July 9, 2016. Called “hello,” the video is short; it’s just two minutes and 44 seconds long. It consists of clips of Mary herself wandering around an affluent-looking suburban house. It’s mostly silent; she doesn’t speak. Instead, she communicates through text that she’s overlaid on top of the footage. The text and the footage both occasionally glitch out, although it’s unclear if the glitching is caused by something otherworldly or whether it’s simply Mary’s aesthetic.

“Hello,” she writes. “My name is Mary.” She doesn’t know much, but here is what she does know:

Her name is Mary.

She thinks she’s in her parents’ house.

She thinks it’s possible that she might be in a copy of her parents’ house.

She doesn’t know how she got here. She woke up here a week prior to the video’s date with no memory of how she arrived.

She also doesn’t remember much about who she is.

She’s stuck inside. The doors won’t open. It’s not clear whether they’re locked or if they… just don’t open. She can’t break the windows, either; she’s tried (unsuccessfully).

There don’t seem to be any other people around.

She found a camera in the house. She started filming things “to keep [herself] occupied.” It’s a Canon, for the curious.

She has long, brownish blonde hair. She hides behind it a lot. She doesn’t typically show her full face in the videos because, as she puts it, she’s shy.

The computers in the house work, and she can connect to the internet. But she can’t see anyone else online — she says it’s “like [she’s] completely alone on the internet.”

Everything in the house is normal during the day; at night, however, she says that “things are very different.”

There might not be any people, but she doesn’t think she’s alone.

She doesn’t know what’s going on.

She doesn’t know what to do.

She needs to get out.

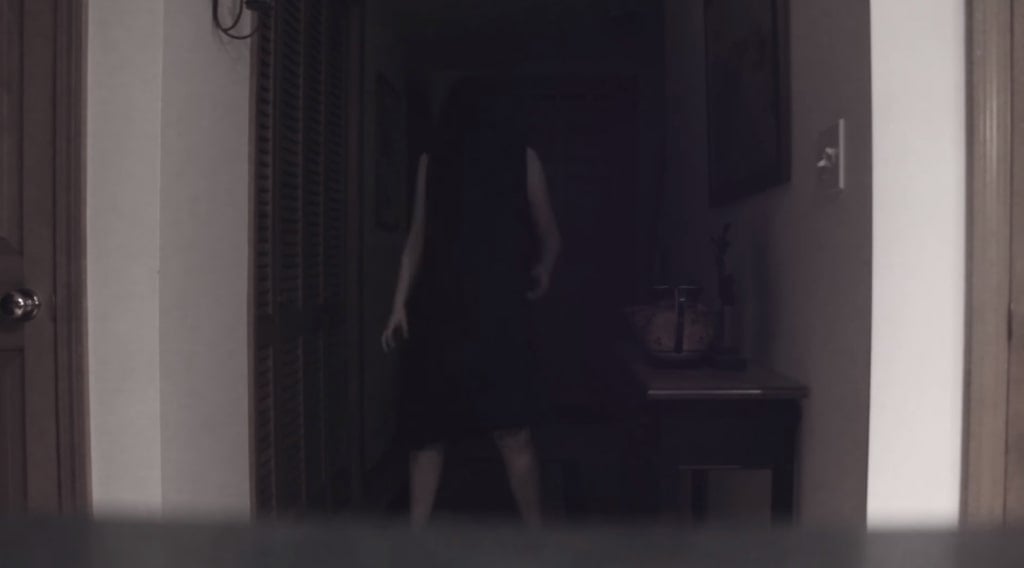

That’s the setup. At the time of this writing, the channel holds 10 more videos, making a total of 11; more, however, are almost certainly to come. She posts a new video roughly every one to two months, the majority of which are three or four minutes long (although there are some exceptions, like the 14-and-a-half-minute epic “DO NOT TOUCH”). They track her as she learns to live in this isolated house. As she meets — and runs from — four different entities who only come out at night: A woman with a black cloth covering her face and head, a masked woman, a creature made of darkness, and the long fingers of disembodied, sentient shadows. As she learns to adjust to this new normal.

So: How does the uncanny fit in with all of this?

Un-Home-Like

Let’s start with the house.

In “The Uncanny,” Freud spends a great deal of time discussing the German words heimlich and unheimlich. Unheimlich is the word for “uncanny” — but its root makes for some interesting analysis, particularly in Mary’s context. Heimlich can mean a great many things (one of which we’ll return to later on), but one of its primary definitions, Freud points out, is “home-like.” Heimlich doesn’t mean a house; the word “house” simply refers to the building itself. The fact that heimlich deals specifically with the word “home” means it brings to mind something more: A place of comfort, familiarity, warmth, and love. To be heimlich is to have all of these home-like qualities. To be unheimlich, therefore, is to be un-home-like, lacking in warmth and comfort. Something that is unheimlich feels… off, somehow.

Mary establishes in “hello” and its successor, July 24’s “dislikeness,” that the house in which she’s found herself does not behave the way a house should: The doors don’t open (although whether they’re locked or simply inoperable remains to be seen), the windows can’t break, and food Mary eats regenerates all on its own. Mary also observed on Twitter that her camera’s batteries never seem to run out, and that her wardrobe offers forth whatever she needs, whenever she needs it. All she has to do is wish for it, and it appears.

All this is very much an example of the familiar made strange, of course; the house is absolutely uncanny in this respect.

But there’s also the idea of unheimlich. Consider the fact that Hi I’m Mary Mary takes place primarily in a home — or at least, it takes place in a house, and since it’s Mary’s parents’ house, there’s also a good chance that it’s where Mary grew up. With this history, the house might also be seen as her home. But it’s… not quite right. It might even be a copy, rather than the real thing.

The setting of the story itself is quite literally unheimlich — it is a home made un-home-like.

There are other things in Mary’s life, too, that don’t behave as they should. The internet, for example: She can connect to it — that’s how she’s able to upload her videos and use social media — but she can’t see anyone else on it. The internet’s sole function is to connect people with each other, but in Mary’s world, it fundamentally fails in its purpose: She can send messages out, but she can’t receive any, and although we, the viewers, can receive the messages she sends out, we can’t send any back to her.

It’s the familiar made strange again.

And there’s more. The lights don’t always work; ergo, they are the familiar made strange. The house appears “normal” during the day, but it’s totally different at night; ergo, it is the familiar made strange. Mary’s reflection when she looks in the mirror isn’t always her own; ergo, it is the familiar made strange. Even the basic structure of Mary’s day has been subverted: By the third video, Aug. 24, 2016’s “goodnight,” she’s sleeping during the day and staying awake at night in order to make sure she never gets caught sleeping by the entities again — ergo, her patterns of sleeping and waking are the familiar made strange.

And, of course, we have Mary herself: She knows her name, but she has no idea who she actually is. She, too, is the familiar made strange.

However, there’s a second definition of heimlich’s worth considering, particularly in relation to Hi I’m Mary Mary: It can also mean a secret — meaning that unheimlich can also refer to a secret that’s been dragged out into the open.

And if we’re going to talk about secrets being unearthed, we need to talk about the entities inhabiting the house with Mary. They’re the key to everything.

The Woman In The Mirror

While it’s true that the woman with the black cloth over her face — a figure I’ve come to think of as “sack lady,” due to the cloth’s sack-like appearance — makes her presence known for the first time at the very end of “hello,” we know absolutely nothing at that point about why she and the other entities are terrorizing Mary. Granted, there are a lot of whys we don’t know at this point: Why Mary is here, why she doesn’t remember who she is, and on and on and on. I suspect all these whys are connected, though — and I would argue that the first solid clue we get about why the entities are after Mary arrives not in “hello,” but in “dislikeness.”

That’s when the masked woman makes her entrance.

Prior to the masked woman’s arrival, Mary, who has been spending a lot of her time searching the house for information about who she is, finds a photograph of herself tucked away in a book. In the photograph, she’s standing in a room or hallway with blue carpeting, wood paneling, and cream-colored walls. She’s wearing a black sleeveless dress and black pumps, and she’s posing with both hands on her hips. It’s a formal occasion; she looks nice.

But Mary doesn’t think so. The text she writes for the image is, bluntly, “I don’t look good in it.”

Then, later on — presumably that night, although not necessarily so — the masked woman appears in the bathroom mirror as Mary gets ready for bed. She wears a black dress (which, honestly, looks quite similar to the one Mary was wearing in the photograph); her hair is dark; the mask she wears presents her face as a cartoonish exaggeration of femininity: Smokey eyeshadow, contoured cheekbones, well-defined eyebrows, a pouting mouth. She strikes similarly exaggerated, model-like poses — and she laughs. She laughs cruelly and continually, pointing at Mary and cackling as though she were the most hilarious joke she had ever heard.

Spliced with this scene, however, is another one — a scene showing Mary taking a pair of scissors to the photograph of herself. Although we’re viewing this scene simultaneously with the mirror scene, it’s clear from the lighting and the angle of the shot that the footage is actually from the earlier, daytime scene in which Mary showed us the photograph. And what that means is that the masked woman didn’t appear until after Mary had destroyed the photograph — a photograph in which, you’ll recall, Mary harshly judged her own appearance.

It seems possible — likely, even — that the masked woman is somehow connected to all the feelings Mary had about both the photograph and herself. What’s more, in “daily life update,” which was posted on March 4, 2017, Mary attempts to beat the masked woman at her own game by dressing up and applying a face full of makeup — only to end up curled up in a ball in tears in front of a full-length mirror while the masked woman continues to laugh at her. It’s clear that Mary’s view of herself is not favorable — and that the masked woman might be a manifestation of those feelings.

The Hunter And The Hunted

I’ll admit that I’m somewhat less interested in the two shadow entities (who, honestly, might just be the same entity in two different forms. Mary does note in a tweet that “there are 4 of them. I think that’s it,” which I’ve taken to mean four entities; however, it’s possible that I’m misinterpreting the tweet). The creature made of darkness and the sentient shadow fingers don’t actually appear to be that dangerous; in each of their appearances — “goodnight?” on Aug. 24, 2016; “the darkness moves” on Oct. 1, 2016; “sleepwalker” on May 5, 2017; and “DO NOT TOUCH” on Oct. 1, 2017 — they seem frightening, yes, but they don’t seem to harm Mary in the same way the two women do. They appear only to want her attention — and, indeed, “sleepwalker” suggests that the creature made of darkness might even be Mary’s own shadow.

The sack lady, however?

She’s something else.

She is, as the video titled “worse” posted on Nov. 18, 2016 calls her, the worst.

Like the masked woman, she wears a black dress similar to the one Mary wore in the photograph she destroyed. We don’t know what color her hair is or what her face looks like; her head is always covered with that black cloth. She is barefoot, and her movements are unnatural.

And each time she appears, she hunts Mary. In “worse,” in “Discovery” on May 27, 2017, in “DO NOT TOUCH” on Oct. 1, 2017, in “hide and seek” on Nov. 7, 2017; and in “check in” on Dec. 31, 2017, she stalks her, chasing her through the house, intent on catching her. The sack lady speaks from time to time, either in a low, rasping growl or in terrifying roar. In “Discovery,” she warns Mary not to try to trick her. In “DO NOT TOUCH,” she screams, “MARY, I HATE YOU” — and, seeming to echo her words, the phrases “how could I let myself get like this,” “I’m so ashamed of myself,” “I’m a failure,” “what is wrong with me,” and “I’m a monster” also flash across the screen in glitched text at various intervals.

But it’s in “hide and seek” that we learn the most — and because of what we learn here, it’s also the point at which my theory fell into place.

“Hide and seek” seems to pick up where “DO NOT TOUCH” leaves off, picking up with Mary in the dark hiding from the sack lady. But then, the sack lady offers a proposal: “Wait,” she says. “Don’t you get tired of running? Let’s play a game. You ask a question, and then I’ll answer… unless I catch you first.”

Mary’s first question, of course, is “Who are you?” — and, as she asks, her figure glitches just a bit. The answer: “You know my name. You know all my names.”

“Where is this place?” Answer: “This is where you desire to be.”

“Who am I?” Answer: “You are nothing.”

“What do you want?” Answer: “I want you to understand.”

“Understand what?” Answer: “That you are worthless. You’re repulsive. That you are not worthy of happiness.”

“Why are you doing this to me?” Answer: “You deserve it.”

And, lastly: “YOU MADE US.”

For me, it was the sack lady’s answer to “Who are you?” and her assertion that Mary made them — all of them — that clinched the idea: All of the entities are aspects of Mary herself. They are all named Mary, and Mary is responsible for creating each and every one of them.

Strangeness And Familiarity

I kind of hesitate to peg a definitive reading to each of the entities — but if I must, I’d argue that they roughly correspond to the following aspects: The masked woman represents both what Mary wishes she looked like, and what she worries others think of her when they look at her. (It’s very Carrie White in that respect — “They’re all going to laugh at you.”) The sack lady represents Mary’s self-loathing. The shadow creature represents how Mary typically feels — that is, invisible. And the sentient shadow fingers are reaching out for attention in the same way that Mary wishes she could. The house, meanwhile, represents the way Mary has isolated herself from everyone around her: She feels alone, and so she is alone.

The reason I hesitate to ascribe fully to these interpretations is because I think the entities are all more complicated than that; they don’t necessarily have to represent just one thing. Complicating the reading of the masked woman, for example, is what we see under her mask briefly in “DO NOT TOUCH”: Her skin veiny and pale and bloody, and her teeth are yellow and decayed. This suggests that her beauty is only surface; what’s more, it suggests that she’s really as ugly outside as she has demonstrated herself to be inside. (She is by far the cruelest of the entities, with “daily life update” perhaps being the clearest example of her cruelty.)

When taken all together, though, the entities paint a pretty thorough picture of how Mary feels about herself. On this level, the uncanny touches Mary in a second way: Not only does she not know who she is, but also, the entities themselves are Mary herself made strange.

And that, I think, is what this whole thing is ultimately about: Hi I’m Mary Mary is a classic story of fighting one’s own demons.

I will readily admit that the entities being aspects of Mary seems like kind of an obvious interpretation — but being obvious doesn’t stop something from being true. Besides, it’s not even the story itself that’s unique here; it’s the way in which the story is being told that is. The uncanny is the primary narrative device, and it nails it in both meanings of the word: There are secrets being brought out into the light — that is, Mary’s true thoughts and feelings about herself — and there are un-home-like figures who give bodies to them all. The meat of the story is all the ways in which the uncanny expresses itself — all the ways in which the familiar is made strange as Mary navigates her situation.

I suspect that if — or when — Mary wins her fight, the strange will be made familiar again; perhaps then she will see herself clearly for the first time.

What’s more, I believe that change is already beginning to happen. Mary stumbled upon a garden in “Discovery” — a beautiful, green, outdoor world where none of the four entities can follow her and where she can be at peace. She can’t get to it all the time — closet door she uses to access it only leads to it sometimes — but according to “check in,” it’s been appearing to her more and more frequently now; she can spend entire nights there when it appears. She gets into it by tricking the sack lady, placing the camera down elsewhere to draw her attention and sliding through the door when she’s not looking. (This is interesting to me; if the camera is a very literal representation of Mary’s point of view, she’s tricking the sack lady by making her think that all she can see is her self-loathing — and then slipping away to a better vision instead.) There’s a new figure in the garden, too — a woman dressed not in black, but white. She still makes Mary feel uneasy, but she hasn’t proven herself as either friend or foe yet. Mary can also take items back from the garden with her, but she can only keep them if she physically holds onto them.

This has some… interesting implications regarding lessons about herself Mary could conceivably learn in the green world.

Oh, and also:

She can see and talk to the rest of the world now.

At midnight on New Year’s Eve, as the calendar ticked over from 2017 to 2018, suddenly, the entire internet became available to her.

Her isolation is lessening.

She’s talking up a storm on Twitter. Why not reach out? Follow along on YouTube at hiimmarymary and on Twitter @hithereiammary.

Oh, brave new world, that has such people in it!

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via hiimmarymary/YouTube (8)]