Previously: Blub Water Park, Germany.

When you think of subway and rapid transit systems in the United States, which cities come to mind first? New York? Boston? Chicago? DC? Whichever one it is, I’m willing to bet that it wasn’t Cincinnati, Ohio. Yes, a Cincinnati subway system was in the cards for the city at one point — but, as you may have noticed, it’s not operational today. It wasn’t just abandoned, though; it was never finished in the first place. The Cincinnati Subway was abandoned midway through construction, when the money to build it ran out and a plethora of other problems plaguing it grew to be too much.

The pieces that were built are still there, though — or at least, some of them are. You just have to know where to go to find them.

Like many cities, Cincinnati’s early public transportation system centered around streetcars — first of the horse-drawn variety; later, cable cars; and later still, electric streetcars. These various iterations of the streetcar operated in Cincinnati from 1859 onward, carrying millions of passengers each year over what would eventually come to encompass 250 miles’ worth of track.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

But as the city grew, a common problem for burgeoning urban landscapes reared its head starting around the late 19th century: Street congestion. Rapid transit had already begun to spring up in other cities across the United States in response to similar issues; the 1897 opening of Boston’s Tremont Street Subway marked, as the Verge noted in 2016, the arrival of the country’s first functional subway tunnel, with New York’s Interborough Rapid Transit line following in 1904 and Philadelphia’s first elevated line opening up in 1907.

So, naturally, that was the direction Cincinnati started moving in, as well. They even had a clever idea for where to put this hypothetical rapid transit system: In the bed of what had once been the Miami-Erie Canal, which was abandoned for commercial use in 1913 after years of steady decline.

The first proposed plan for a subway system in Cincinnati, then called the Rapid Transit Loop, was produced in 1912 by Bion J. Arnold, then refined in 1914 in the Baldwin-Edwards Report, according to local Cincinnati writer Jake Mecklenberg. (Mecklenberg is, at this point, probably one of the foremost experts on the history of the Cincinnati Subway; he has written and run the transit-focused website Cincinnati Transit, which includes an extremely in-depth section on the subway, since 1999. He expanded this section into a full book, Cincinnati’s Incomplete Subway: The Complete History, in 2010.) The Baldwin-Edwards Report included several possible route options — and by 1916, near-unanimous political and popular support for a rapid transit system in Cincinnati had led to a $6 million (nearly $150 million in 2020, accounting for inflation) bond issue for the fourth route, which would have covered nearly 16 and a half miles of ground. 6.4 miles of that would have been subway; 0.15 miles would have been tunnel; 1.44 miles would have been elevated; and the remaining 8.47 miles would have simply been above ground in the open.

But then, in 1917, the United States entered the First World War, which, for a variety of reasons, delayed the project for a number of years: The canal wasn’t drained until 1919 and construction didn’t commence until 1920. Furthermore, by the time things finally could get under way, the original $6 million was no longer believed to be enough for the route as planned, which resulted in modifications being made in order to reduce costs.

And unfortunately, the money problems would only get worse. By 1921, post-war inflation had gotten so bad and construction costs so expensive that it was determined the money allotted for the rapid transit line would only cover 11 miles of the planned 16; accordingly, the entire eastern part of the loop was eliminated. Additionally, writes the Verge, poor planning led to houses along the route suffering severe damage during construction, leading to a slew of lawsuits. And with Prohibition shutting down the many breweries, pubs, taverns, and bars that helped fuel the city’s economy, Cincinnati’s financial situation as a whole was increasingly shaky — which, in turn, meant that the massive rapid transit project was also on increasingly shaky ground.

Alas, this perfect storm of poor management and the larger economic context did its worst: Construction halted in 1925 with only seven miles of the route having been completed. Although a 1927 report compiled by a New York consulting firm laid out a solid plan for how the project might eventually reach full completion, the $10 million bond it would cost to do so was not issued; then, once the Great Depression arrived in 1929, circumstances simply didn’t allow for any new construction to begin.

And so, the unfinished remnants of what would have been the Cincinnati Subway were abandoned, closed up and left alone below (and, in some cases, above) the city streets. Of the stations that had actually been built, the Clifton Avenue, Ludlow Avenue, and Marshall Avenue stations have been completely demolished; meanwhile, the Brighton Place, Linn Street, Liberty Street, and Race Street stations remaining standing but disused; meanwhile. The city has spent years covering up or removing any entrances to these stations, or to elsewhere within the system still left — and although the Cincinnati Museum Center used to run the occasional tour into the tunnels, these tours were discontinued in 2016 due to the results of a risk assessment carried out after the previous year’s tour.

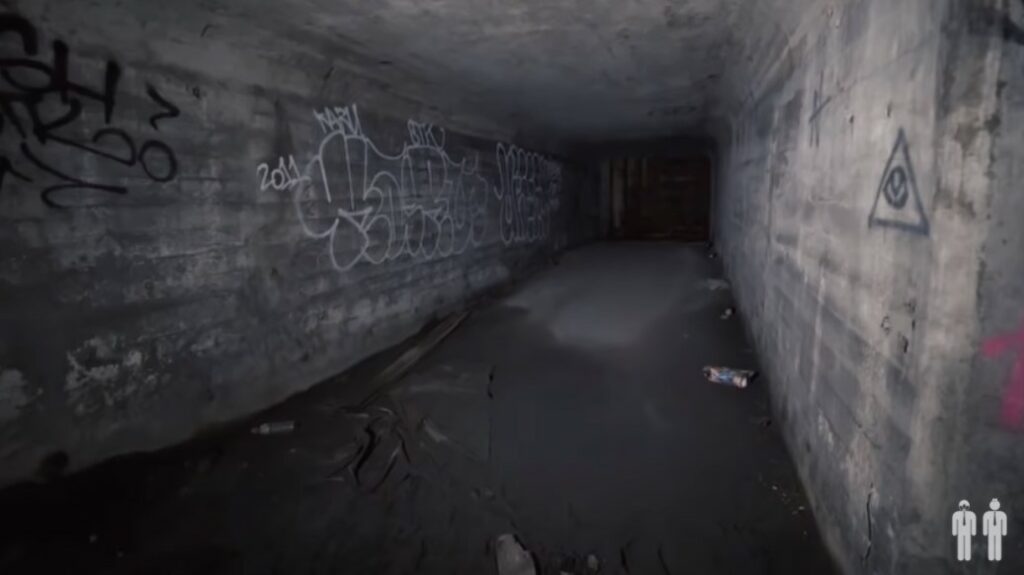

But that hasn’t stopped intrepid urban explorers from venturing into the tunnels when possible, despite the fact that it’s extremely dangerous (and, depending on how access is attained, legally dubious) to do so.

As architect and photographer Zach Fein points out in his feature on the Cincinnati Subway, each of the stations that are still standing “have their eccentricities.” Brighton seems to be the most interesting, architecturally speaking; it’s quite complete, although — as is the case for all the stations — no track was ever laid there. Linn Street, meanwhile, is the least interesting, from a visual standpoint; the station itself has actually been walled up, meaning that the platform isn’t even visible from the tunnel anymore — all you see is a long line of concrete. Race Street was meant to have been one of the system’s main hubs, so it’s the biggest of the stations — and also one of the darkest and dampest.

And then there’s Liberty Street. Liberty Street is by far the most infamous of these remaining abandoned stations — a reputation it holds largely due to the brief, disastrous attempt to turn into a fallout shelter that occurred in the 1960s.

The idea of retrofitting the abandoned subway stations and tunnels into a facility suitable for housing Cincinnati’s residents in the event of a major disaster was first floated during the Second World War, according to Cincinnati Magazine; at the time, the suggestion was to use the underground infrastructure to shelter from air raids. By the early 1950s, the purpose of such a retrofit had morphed from air raid shelter to bomb/nuclear fallout shelter — and in the early 1960s, with the Cold War looming large in the landscape, the project was finally put in motion. Construction began at the end of April in 1962, with plans for the Liberty Street station including first-aid rooms, kitchens, generators, decontamination showers, and, uh… well, the news reports called it “dead body storage,” but I suppose a slightly better name for it might be morgue space. The idea was for the shelter to be capable of housing 500 people for up to two weeks at a time.

Issues, however, cropped up almost immediately. For one thing, plans to dig a well and install a pipe system to supply the shelter with running water went sideways when the digging began, and no water — literally none — was to be found. Vandals also repeatedly managed to find their way in and wreak all kinds of havoc before their access point was found and blocked. And — most pressingly — the organization and management of the shelter was a disaster: No one knew who held the key for the place, so in the event of an actual emergency, no one knew who was supposed to be responsible for unlocking the place.

By the end of 1963, the whole thing had proved to be such a misstep that the Liberty Street station was abandoned once again. To this day, Cincinnati remains subway-less, with all of its traffic — automobile, foot, and public — occurring on the city’s sureface.

But buses aren’t the only public transportation option in Cincinnati today; perhaps somewhat surprisingly, the streetcar system, which had shut down in its original form in 1951, made a comeback in 2016. Now called the Cincinnati Bell Connector, the light rail system operates on a 3.6-mile loop that hits such landmarks as Fountain Square and the Banks.

Will the subway ever see another revival? That remains unknown. But for now, perhaps it’s enough to know that there’s a secret hiding just below your feet — as long as you know where to look.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[All photos available via Flickr or Wikimedia Commons under CC BY 2.0, CC BY-SA 2.0, CC BY-SA 3.0, or CC BY-SA 4.0 Creative Commons licenses or in the public domain. For credits and source links, see captions of each individual photo.]

Leave a Reply