Previously: Zener Cards.

If you’re the kind of person who’s interested in the strange and spooky, I can all but guarantee you’ve seen at least one spirit photograph in your lifetime. Maybe you’ve seen the picture of the Brown Lady of Raynham Hall. Or maybe you’ve seen the Amityville ghost boy photo. Or maybe you’ve just seen one of the many, many photographs of so-called “orbs” that often dominate the conversation about paranormal photography these days. No matter what you’ve seen, though, you might have wondered how spirit photography works, exactly — whether you’re skeptical of these kinds of images or whether you think there might be some truth to them.

So let’s take a look, shall we?

Spirit photography grew up in tandem with two other notable moments of the 19th century: The development of photography, and the growth of the Spiritualist movement. Although a few techniques for capturing photographic images were developed in the 18th century, it wasn’t until Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre introduced his daguerreotype process to the world in 1839 that photography became widely available; other processes soon followed, with the first Kodak camera hitting the market in 1888. Meanwhile, the Spiritualist movement was kicked into high gear in 1848 by the Fox sisters’ séance shenanigans in Hydesville, New York; it continued to gain steam throughout the 19th century, especially as the United States reeled from the loss of a generation of young men due to the American Civil War.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now!]

And when the two came together? That’s how we got spirit photography — although unlike Spiritualism and early photographic methods, spirit photography has proved to have a surprising degree of lasting power. Although the equipment, techniques, and technology used to capture ghost photographs has changed in the centuries since spirit photography was first developed, the goal of the practice remains the same: To capture with the camera what we miss with the naked eye.

But before we can talk about how it actually works, we need to talk about where spirit photography came from. So — let’s get to it.

A Brief History Of Spirit Photography

Given that photography itself is only about 200 years old — small potatoes, in the grand scheme of things — it’s unsurprising that spirit photography is also similarly recent. Its discovery is usually credited to William H. Mumler, who took what’s considered to be the very first spirit photograph in the early 1860s. (This claim is contested; according to some sources, a photographer in New Jersey named W. Campbell took a photograph of an empty chair in 1860 which showed the ghostly figure of a small boy seated in the chair when the image was developed. However, as the Paranormal Encyclopedia notes, “Campbell was never able to replicate this event and it is not well remembered by historians of the art.”)

Mumler wasn’t a photographer by trade — he was a jewelry engraver — but he dabbled in photography in his spare time, experimenting with the emerging technology and seeing what this new art was capable of accomplishing. He was surprised one day to find that a self-portrait he had taken contained more than just his own visage; he also saw the faint image of a girl — a girl he identified as his cousin, who died more than a decade earlier.

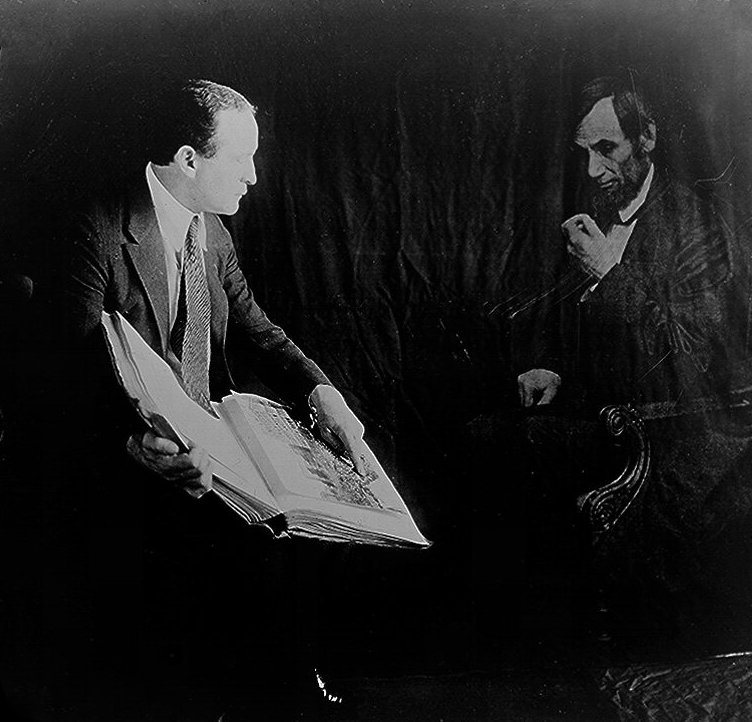

Mumler already had ties to the Spiritualist community in Boston, where he lived at the time; his wife, Hannah, was known as a “healing medium.” As such, it’s somewhat unsurprising that Mumler’s photograph of his “cousin’s spirit” would make its way to Spiritualist circles, although he would later claim that he’d merely stumbled into the community. Spiritualist papers such as The Banner Of Light trumpeted Mumler’s seemingly miraculous image — as well as successive images — as totally legitimate . Mumler soon went into business shooting spirit photographs, charging visitors to his studios the extravagant fee of $10 — the equivalent of more than $280 today — and opened up mail orders for $7.50 (around $212 today). His most famous subject was Mary Todd Lincoln — with her husband, the late Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States, hovering in the background.

Of course, Mumler’s work didn’t convince everyone; indeed, these days, it’s pretty clear that he faked his photographs by re-using photographic plates, which created afterimages of the subject depicted in the first photograph created with the plate in subsequent photographs of other subjects made with the same plate. And although he had plenty of supporters, the growing number of detractors convinced him to move from Boston to New York — where the law finally caught up with him.

Ultimately, his undoing was sloppiness: As Joe Nickell wrote for the Skeptical Inquirer in 2008, “Mumler was exposed as a fraud when people recognizes that some of the supposed spirits were still among the living.” He was tried for fraud in 1869, with P.T. Barnum — noted showman and master of “humbug,” as he called it — among those who testified against Mumler, providing proof of how easily such images could be falsified.

Even so, though, the prosecution failed to produce the evidence necessary to convict Mumler. He was acquitted, although he had ceased his activity in the world of spirit photography within a few years following the conclusion of his trial.

But Mumler was far from the only spirit photographer working at the time; others included Albert von Schrenck-Notzing, who specialized in photographing séances, and William Hope, who was later exposed as a fraud. Nor would any of these creators be the last to claim to have captured evidence of the supernatural on camera: Spirit photography continues to be a commonly used paranormal investigation technique today — and the argument about whether the photographs produced by it really do show supernatural activity wages just as fiercely as it did nearly two centuries ago.

So how does spirit photography work? As always, it depends who you ask.

The Believer’s Argument

Many who believe in the camera’s ability to capture spirits and other entities on film (or in image files, as the case often is today) cite Mumler’s work as credible. After all, Mumler was exonerated; during his trial, the prosecution was unable to prove beyond reasonable doubt that his photographs were deliberately perpetrated hoaxes, leading to his acquittal. And although many had accused him of forgery, none of the investigations of his work that were carried out at the time were able to explain exactly how he captured the images he captured.

Indeed, Mumler welcomed investigators to come take a look at his studio, his techniques, and his photographs — and many who did so came away from the experience believing wholeheartedly in Mumler’s abilities. For example, wrote photographer William Guam in The Journal Of The Photographic Society Of London in 1863:

“Having been permitted by Mr. Mumler every facility to investigate, I went through the whole of the operation of selecting, cleaning, preparing, coating, silvering, and putting into the shield the glass upon which Mr. M. proposed that a spirit-form and mine should be imparted, never taking off my eyes, and not allowing Mr. M. to touch the glass until it had gone through the whole of the operation. The result was, that there came upon the glass 3 picture of myself and, to my utter astonishment — having previously examined and scrutinized every crack and corner, plate-holder, camera, box, tube, the inside of the bath, &c. — another portrait.”

But when it comes to explaining exactly what goes on when a spirit photograph is taken (especially in the modern day), there isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. As Dale D. Kaczmarek of the website Ghost Research told How Stuff Works in 2012, authentic spirit photographs “don’t fall into the category of easily explained”; as such — not unlike a number of other modern ghost hunting and paranormal documentation and investigation techniques — those who believe in spirit photography don’t necessarily agree on exactly how or why it works. They just know it works.

There are, however, a few different theories. One is sort of based on the same principal that might explain spirit boxes: Much the same way the radios used to make spirit boxes provide raw audio out of which an entity might construct a “voice” for itself, photography might provide another kind of raw material which an entity can manipulate in such a way as to give itself something else it otherwise lacks: It provides light which can be used to create a physical form — or at least, the impression of one.

Another school of thought suggests that, because spirits and other entities largely occupy the portions of the electromagnetic spectrum that aren’t visible to the human eye, cameras can catch what we don’t. Humans are only capable of seeing a small portion of this spectrum, appropriately termed the visible spectrum; anything outside of that, we can’t detect unaided. That’s where the camera comes in: It can “see” what we can’t and translate it into an image we can see.

According to the website Ghostly Activities, digital cameras are particularly good for spirit photography due to their range of settings and capabilities — including being able to “capture different light ranges.” Per the site, the key is to set your camera to take RAW format photos, as opposed to JPEG or PNG format, the reason being that “JPEG and PNG files drop a lot of light data when the camera makes these image formats.” RAW files, however, “[capture] the most light ranges,” thereby giving it the best chance of picking up something we might otherwise miss.

The entities that manifest in photos today are less likely to appear as the perfectly-presented, full apparitions seen in the spirit photographs of the 19th century (which some might argue is actually proof that Mumler’s photos, and spirit photography as a whole, is bunkum — just, y’know, for whatever that’s worth); indeed, they might appear in any number of forms. If you see white, grey, or black clouds of mist or fog that swirl about or hover in such a way as to suggest sentience, for example, you might be seeing ectoplasm or ecto-mist. A swirling spiral of mist or light, meanwhile, is what’s referred to as a funnel ghost. There are orbs, of course — balls of light that range in size from very small to very large and which move about seemingly with a mind of their own. Sometimes, you might in fact see an apparition of some sort — a hazy outline of a person; a strange shadow; a face emerging out of the darkness; and so on and so forth.

An entity may not fall under any of these specific categories, though; Kaczmarek told How Stuff Works that it’s common for true spirit photographs to merely display “a streak of light, a strange light, or fog.” But regardless as to what you see, what each and every spirit photograph bears in common is this: Whatever you’ve found in your photograph wasn’t present at the time you took the photo — or at least, it wasn’t visible to your naked eye. According to Kaczmarek, the key to determining whether an image is authentic is to rule out any and all possible natural explanations for what you’re seeing before entertaining the idea that it’s an actual spirit.

And that’s where the skeptic’s argument comes in.

The Skeptic’s Argument

Those who don’t believe in spirit photography are well-versed in the myriad natural explanations for the kinds of phenomena observed in these images. Multiple exposures, motes of dust, reflections, flare, flash, fog, or even your own breath condensing in the air could account for any of the “entities” you might see in a so-called spirit photograph — particularly if the photographer is an amateur who doesn’t know how to otherwise counteract these kinds of errors in their shooting technique. Orbs are particularly contentious; indeed, many who do otherwise believe in spirit photography do not consider orbs to be a reliable indication of paranormal activity. They’re almost always what’s called backscatter — bits of dust, pollen, precipitation, bugs, or anything else that might be floating through the air which have caught the light of a camera flash and reflected it back into the lens. It looks cool, but it’s rarely — if ever — evidence of paranormal activity.

It’s also worth considering that sometimes when we see “ghosts” in photographs, it might just be our brains spotting patterns where there aren’t any — that is, it’s a result of the psychological phenomenon known as pareidolia. I’ve spoken about pareidolia at length before — the human mind’s tendency to impose order over chaos is well-documented — so I won’t go over it again now; it is, however, a very, very common phenomenon, so when you think you’re seeing a face in the window in a photograph of a spooky, abandoned house, know that it’s a distinct possibility your brain might just be trying to make sense out of some visual noise.

And, of course, there’s no shortage of hoaxes — faked photographs manufactured with the use of in-camera editing tricks or with photo manipulation software.

Even though Mumler was acquitted, we know that such tricks were employed even during the early days of spirit photography. It’s well-documented; they’re frequently discussed in books and writings from the era. In 1856, for example — several years prior to Mumler’s production of the first acknowledged spirit photograph — scientist Sir David Brewster wrote in his book The Stereoscope: Its History, Theory, and Construction:

“For the purpose of amusement, the photographer may carry us even into the realms of the supernatural. His art… enables him to give a spiritual appearance to one or more of his figures, and to exhibit them as ‘thin air’ amid the solid realities of the stereoscopic picture. While a party is engaged with their whist or their gossip, a female figure appears in the midst of them with all the attributes of the supernatural. Her form is transparent, every object or person beyond her being seen in shadowy but distinct outline.”

Brewster’s technique made use of the long exposure times required to actually take photographs at the time, having a “spirit” (that is, a living person posing as a spirit) enter the frame for the last few seconds of exposure and exiting again before the exposure completely finished. The resulting image featured both the living subjects and a spectral figure — that is, a spirit photograph.

Inventory and photographer Walter Woodbury described a similar technique in Photographic Amusements in 1896; in Woodbury’s version, the living subject and the “spirit” were both positioned in the frame at the start, with the “spirit” being removed early on:

“It is a very simple matter to make quite convincing ghost pictures…We must first prepare our ‘ghost’ by dressing someone in a white sheet. Then we pose the sitter and the ghost in appropriate attitudes and give part of the required exposure. Then, leaving everything else just as it is, we remove the ghost and complete the exposure. On developing the film, we find the sitter and the background properly exposed and only a rather faint image of the ghost, with objects behind it showing through on account of the double exposure.”

And in 1897, magic historian and amateur magician Henry Ridgely Evans wrote of double printing and double exposure as methods by which one could produce fraudulent spirit photographs in The Spirit World Unmasked: Illustrated Investigations Into the Phenomena of Spiritualism and Theosophy:

“There are two ways of producing spirit photographs, by double printing and by double exposure. In the first, the scene is printed from one negative, and the spirit printed in from another. In the second method, the group with the friendly spook in proper position is arranged, and the lens of the camera uncovered, half of the required exposure being given; then the lens is capped, and the person doing duty as the sheeted ghost gets out of sight, and the exposure is completed. The result is very effective when the picture is printed, the real persons being represented sharp and well defined, while the ghost is but a hazy outline, transparent, through which the background shows.”

In the age digital photography, photo manipulation is easier and more accessible than ever. You don’t even need expensive software like Adobe Photoshop to do it — there are loads of free yet powerful Photoshop alternatives available for download at the click of a button, with even more tutorials to teach you exactly how to make these spooky images just a Google search away. The images you can produce by these means can be quite effective (hi there, Dear David); a number of artists and graphic designers even specialize in creating these kinds of works, which function as fun and chilling, short, pieces of visual storytelling (check out Trevor Henderson, aka SlimySwampGhost, for some particularly good stuff).

What Do You Believe?

Given how many other explanations there are for an “entity” seen in a spirit photograph — especially these days, when technology that can be used to fake such images to great effect is so prevalent — it takes a lot for me to believe that I’m genuinely looking at something paranormal. In fact, I might even go so far as to say that until I take a photograph in which something appears which I honestly can’t explain myself, I’m an out-and-out spirit photography skeptic. And since that hasn’t happened… well, you do the math.

But you might feel differently — and, indeed, it’s possible that both the skeptic’s argument and the believer’s argument might be right at different times/ Sometimes, so-called “spirit photographs” might just be an instance of dust motes reflecting in some odd ways, and others, they might really have captured something inexplicable. As American Hauntings notes, this might even be true of Mumler himself: It’s possible that Mumler “may have actually captured something genuine in some of his photos,” while also “[supplementing] his authentic photos with fraudulent ones” in order to bring in more money.

The jury’s still out on this one. In the meantime, I’ll send you over here to look at some of the most famous spirit photos in history. What do you think?

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via congerdesign (1, 2)/Pixabay; Wikimedia Commons (1, 2, 3, 4), available via public domain; Balliballi, Llamnuds/Wikimedia Commons, made available in the public domain by the photographers]

Leave a Reply