Previously: Automatic Writing And The Unconscious Mind.

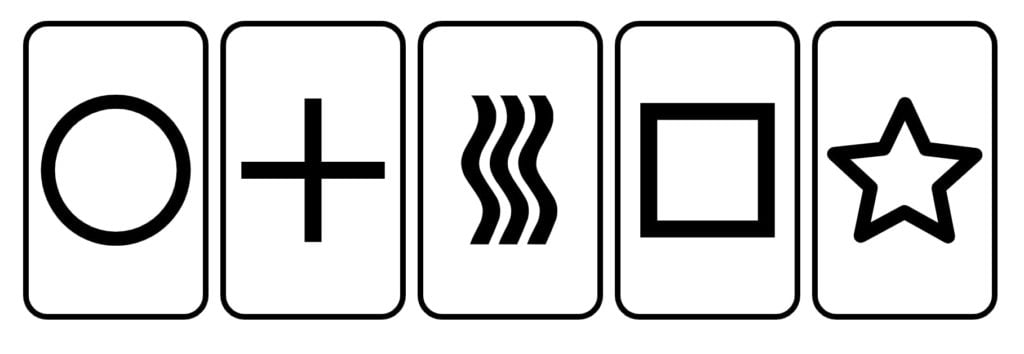

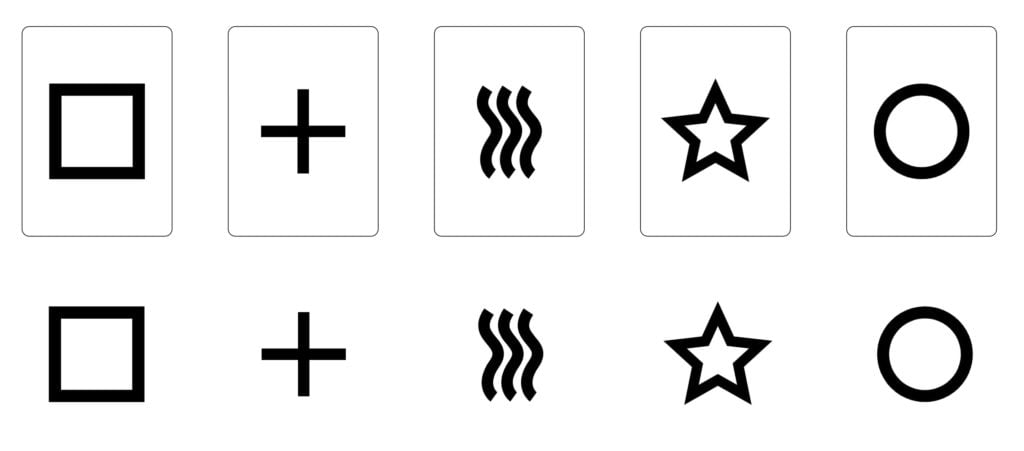

Even if you don’t recognize the name, I’d be willing to bet you know what Zener cards, also known as ESP cards, are: They’re those sets of cards marked with five symbols — a star, a circle, a cross, three wavy lines, and a square — which are ostensibly used to test how psychic you are. You remember that one scene in Ghostbusters? Or the one in episode five of The Prisoner? How about the character Shiki’s battle convention in the video game The World Ends With You? Those all show Zener cards in action. But if you’ve ever wondered how Zener cards work? Well, that depends on how you feel about extrasensory perception, or ESP.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

The concept of ESP has been around for centuries; it’s been a tenant Jainism for many thousands of years, although the term itself didn’t exist in English until much later on. The English term is often said to have been coined by British explorer Sir Richard Francis Burton in 1870, although it’s not clear whether that little tidbit is apocryphal or not. In any event, by the 1890s, it was in use by researchers into psychical phenomena to describe abilities ranging from hypnotism to mediumship — but it wasn’t until the 1930s that it became widely used, due largely to the creation of and research into Zener cards.

As with many paranormal topics, there are those who believe in ESP and those who don’t — and, accordingly, those who believe in the efficacy of Zener cards and those who don’t. We’ll take a look at both arguments today — but first, let’s talk a little about where Zener cards came from in the first place.

A Brief History Of Zener Cards

Zener cards got their name from their inventor: Perceptual psychologist Dr. Karl Edward Zener. Born in 1903 in Indianapolis, Indiana and educated at the University of Chicago and Harvard — he received a Ph.B (Bachelor of Philosophy) from the former and an MA and Ph.D. from the latter — he spent the majority of his career at Duke University, whose faculty he joined in 1928. He spent 20 of his 36 years at the university as its Director of Graduate Studies in Psychology and chaired the department from 1961 until his death in 1964.

Meanwhile, Joseph Banks Rhine, more commonly known as J. B. Rhine, had previously arrived at Duke in 1927. Born in 1895 in rural Pennsylvania, Rhine spent two years during the First World War as a marine before earning both an MA and Ph.D. in botany from the University of Chicago. However, after hearing Sir Arthur Conan Doyle speak about psychical research and spiritualism in 1922, along with learning of an experience a neighbor of a U Chicago professor allegedly had of having what turned out to be an accurate vision of her brother’s death, he switched gears: Beginning in 1926, he devoted himself to psychical research and parapsychology, with a particular interest in the field of mediumship. When he came to Duke University in 1927, it was to work under British psychologist William McDougall, a former president of the British Society for Psychical Research (BSPR) who both established Duke’s psychology department and made it one of his goals to conduct psychical research within a university setting.

Earlier in his career, Zener focused primarily on classical conditioning of the sort exemplified by Pavlov’s dogs. Indeed, throughout the 1930s, Zener operated one of the only Pavlovian conditioning labs in the United States. But during this time, he also connected with J. B. Rhine, who had begun his own series of experiments in which participants attempted to guess numbers or letters written on cards sealed in envelopes. Using playing cards for this purpose, however, turned out to be something of an issue; since the participants typically had a great deal of familiarity with 52-card, French-suited decks, Rhine found that his participants often had “favorite” cards they would guess more frequently than any others. In order to account for this bias, Rhine determined that he needed a new deck — one with which none of his participants would have any degree of familiarity.

So he reached out to Karl Zener, who created what’s now known alternately as Zener cards or ESP cards: A deck of 25 cards — five each of five different symbols. The symbols included in the original deck were a star, a circle, a cross, a set of three wavy lines and a rectangle, although the rectangle was later changed to a square. Together, Rhine and Zener began using these cards in their experiments in the hopes that it would stamp out the issues brought on by using standard decks of 52 playing cards.

Rhine and Zener’s cards and the experiments they conducted with them were themselves actually variations on an existing technique. Card-guessing, in which participants attempted to identify characteristics of cards drawn out of ordinary, 52-card, French-suited playing card decks, had been used in psychical research for some decades prior to Rhine and Zener’s research; particularly popular in the 1880s, the technique again gained prominence between in the mid-1920s, courtesy of Ina Jephson of the BSPR. Jephson’s experiments involved drawing cards from a deck of 52 and having participants make five sets of five consecutive guesses before returning the card to the deck. Employing a system created by statistician R. A. Fisher, Jephson sought to “evaluate the varying degrees of success that might be observed in card guessing: to determine, in effect, how much more improbable it would be to identify the four of hearts as the five of diamonds than as the king of clubs,” as Michael McVaugh and Seymour H. Mauskopf put it in their 1976 article “J. B. Rhine’s Extra-Sensory Perception and Its Background in Psychical Research,” published in the University of Chicago Press’ journal Isis.

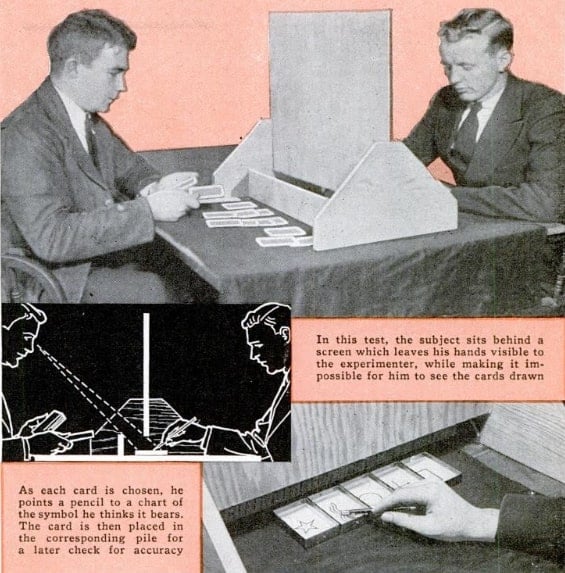

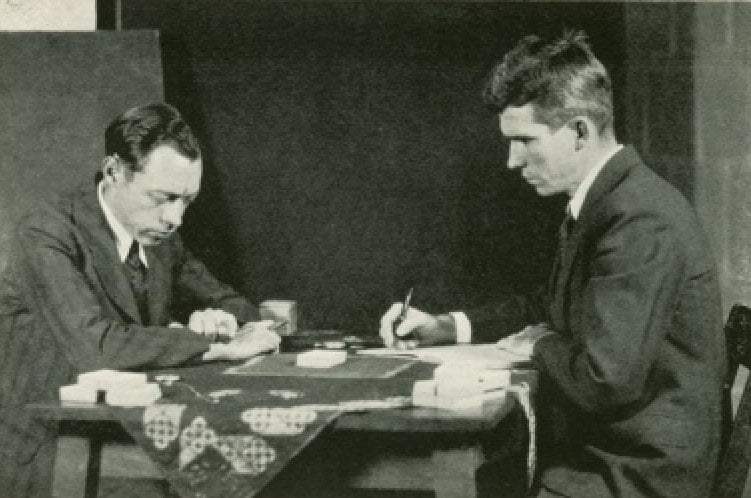

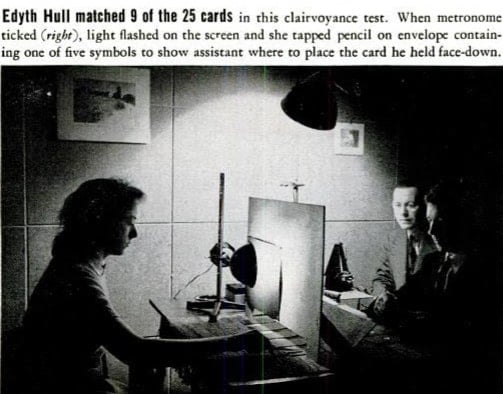

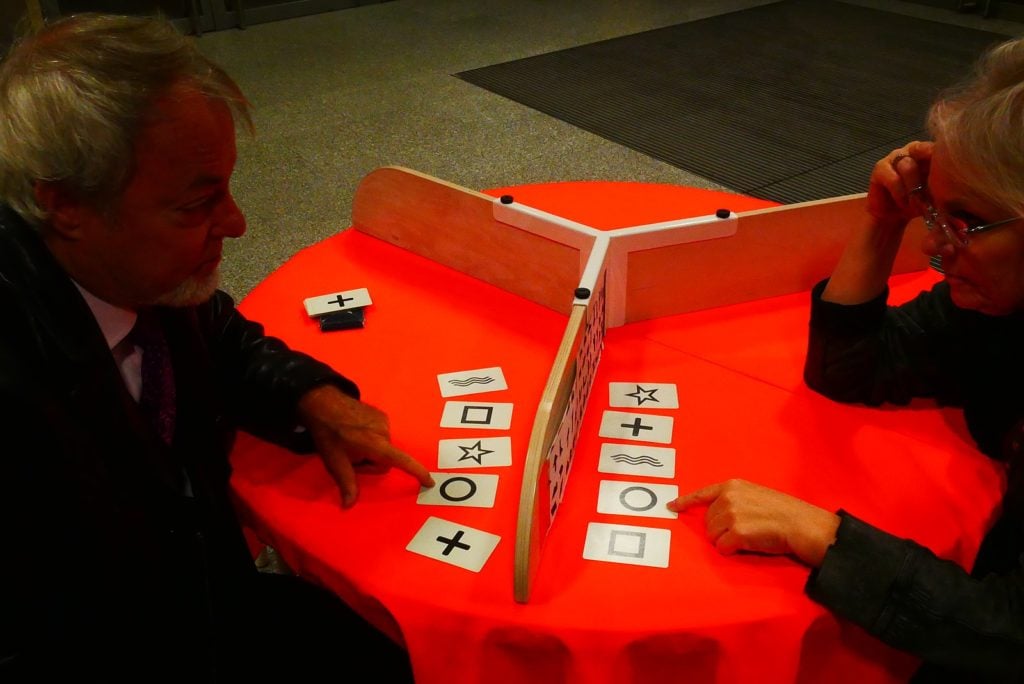

Rhine and Zener were both familiar with Jephson’s work, so according to Rhine himself, they based their own methods off of the technique she had established. For a typical clairvoyance test, the deck of Zener cards would be shuffled and hidden from the participants, either by a screen or by sealing them in envelopes. The participants would then guess the order of the cards, one by one, until they had worked through the full deck of 25 cards. As they made each guess, their responses were recorded by a researcher; then, after the participants had finished all their guesses, the researcher checked the order in which the participants believed the cards had been dealt against the actual order while the participant looked on. Later, the method was adapted to test telepathy, rather than clairvoyance; in these tests, one participant, termed the “sender,” would look at the cards one by one, either screened off from another participant (the “receiver”) or in a different room entirely, and attempt to “send” an image of the card telepathically to the receiver. The receiver would then try to guess what the sender was attempting to communicate with them. As Atlas Obscura noted, the probability of guessing the first card correctly was one in five; however, the probability of guessing 10 or more cards correctly was only about one in 20.

Between 1931 and 1933, Rhine and Zener identified and studied eight participants who had seemingly demonstrated extraordinary results — like, for example, AJ Linzmayer, a sophomore at Duke who guessed 404 cards correctly out of 1,500. Chance accounted for about 300 of those correct guesses, leaving 100 as what the researchers believed might be evidence of extra-sensory perception, or ESP.

So: How were the cards supposed to work? There is, as always, a believer’s argument and a skeptic’s argument. Let’s start with the believers.

The Believer’s Argument

Although I’ve been referring to participants “guessing” the shape on the cards in each of Rhine and Zener’s trials, believers wouldn’t call it “guessing” for those with a particular success rate. Statistically, it’s to be expected that any one person working their way through all 25 cards would get five cards correct — 20 percent of the deck — purely by chance. If you’re able to get more than five cards correct — that is, if you’re able to identify more than 20 percent of the deck — then you may have achieved a statistically significant result. And if you’re able to get more than seven cards correct, or about 28 percent of the deck, then your results may not be guesses; they may be a result of ESP. (As an instructor at the Association for Research and Enlightenment — an organization founded by clairvoyant Edgar Cayce in 1931 — put it to skeptic Michael Shermer back in 1992, “anything above seven is evidence of ESP.”)

Defined as any kind of perception that “involves awareness of information about events external to the self not gained through the senses and not deducible from previous experience” — that is, a “sixth sense,” so to speak — ESP can take a lot of forms. In Rhine and Zener’s original method, where single participants simply attempted to guess the order in which the deck of Zener cards was dealt out, the form tested was clairvoyance, or the ability to “see” things distant in time, space, or both to the clairvoyant. (The word “clairvoyance” literally means “clear vision.”) In the case of the later method, where pairs of participants worked together, with one trying to “send” an image of a card to the other, the form tested was telepathy, or the transmission of information from one person to another without using any of the traditional five senses.

Having ESP-related abilities might explain how a given individual might get more cards correct than the average — they’re not “guessing” them; they’re, say, “seeing” them in their mind’s eye. But how does ESP work, more broadly? That’s… a little less clear-cut. As How It Works notes, there isn’t really a consensus on it.

According to one theory, ESP is thought of as “energy moving from one point to another point”; more specifically, it’s believed to be a type of electromagnetic wave that’s capable of traveling and transmitting in similar ways to light and radio waves; we just haven’t figured out a way to detect it or measure it scientifically yet. According to another theory, though, ESP is a result of a sort of “spillover” of information from an alternate reality or universe that’s bumping right up against our own. Yet another posits that time flows not just in one direction, but in both directions — backwards and forwards — which allows us to sense things that haven’t technically happened yet in our own timeline. There are countless theories out there, none of which has either been conclusively proven or disproven — although that whole “time flows in both directions” thing did make the news a few years ago as proof not that ESP exists or how it works, but as evidence that science is, in a word, broken.

There isn’t a consensus on who might have ESP-related abilities or how they access them, either. Some believe that everyone has the capacity for ESP — and, indeed, that we often access these abilities without realizing it all the time. Others believe that only some people — psychics, mediums, and the like — have these kinds of abilities, and that they must enter a trance-like state in order to access them, similarly to how mediums conducted seances during the height of the Spiritualist movement. And still others think the answer is somewhere in the middle — that everyone has the capacity for ESP, but that some people are more sensitive to it than others.

But even if believers don’t necessarily all have the same ideas about how ESP works, they do agree that it works, full stop. The 33 original studies conducted by Rhine and Zener are often pointed to as evidence. Of these original studies, 27 were initially interpreted as statistically significant, which the Parapsychological Association calls “an exceptional record, even today.”

The Skeptic’s Argument

To skeptics, meanwhile, Zener cards don’t prove anything about the existence of ESP; all they demonstrate are flawed science and how probability works.

On the subject of flawed science, Rhine and Zener’s original experiments have actually been largely discredited now due to issues with the methods they used. One of the biggest problems, for example, was sensory leakage — that is, the participants who guessed a high number of cards correctly could have received the information in any number of standard ways, even inadvertently, as opposed to through ESP. As the Skeptic’s Dictionary notes, we know for a fact that some of the decks of cards Rhine used were thin enough for participants in the experiments to actually be able to see the images through the backs of the cards. The participants could very well have either seen through the cards without realizing it and unconsciously based their guesses on what they didn’t know they’d seen — or they could have known quite clearly what they were seeing and straight-up cheated.

On the subject of cheating, it’s worth noting that people didn’t generally think Rhine was cheating to get his results; however, “many thought he had been duped by his subjects several times,” observes the Skeptic’s Dictionary. Continues the resource:

“According to Milbourne Christopher, ‘there are at least a dozen ways a subject who wished to cheat under the conditions Rhine described could deceive the investigator.’ … Also, once Rhine took precautions in response to criticisms of his methods, he was unable to find any high-scoring subjects to match his early phenoms. … Rhine even used a magician to observe [Hubert] Pearce [who once correctly guessed all 25 cards]; his performance sunk back to chance levels. When not so observed, his scores were significantly higher.”

Rhine also just kept finding ways to explain away some of the less-than-stellar results. For example, when Hubert Pearce’s scores went back to normal chance levels after the experiments he participated in were controlled for a few issues, Rhine wasn’t content to take that as evidence of regression toward the mean — a demonstrable phenomenon that’s been observed time and time again in luck- and chance-based situations — but rather as “the decline effect”: The idea that “continued investigation” can result in a reduction of psychical abilities due to boredom or fatigue. He had a tendency to shape the facts such that they fit his beliefs, rather than letting his beliefs be informed by what the facts were saying.

It’s also worth noting that most Zener cards test fit within the normal distribution — that is, they make a bell curve. If we calculate the results according to probability, most people — around 79 percent — will get between three and seven cards correct. The probability of guessing at least eight cards correctly is 10.9 percent — that is, if you test 25 people, you can probably expect a few of them to end up with scores of eight or more. The chances of getting 15 cards correct are about one in 90,000, while the chances of getting 20 out of 25 correct are about one in five billion. If you guess all 25 correctly — as Huber Pearce claimed to have once — then congratulations: You had a chance of about one in 300 quadrillion of doing so, and you did it.

But just because something is unlikely to happen doesn’t mean that it can’t happen — so assuming that, say, Pearce didn’t cheat or leverage sensory leakage that time he guessed all 25 cards (and that’s a big assumption to make), his results still could have arisen from pure chance. Would that be an incredible instance of luck? Heck yes. Is it impossible? Nope — just improbable.

Although the Parapsychological Association’s page on Rhine claims that 20 of 33 “independent replication experiments” conducted at other labs within five years of the publication of Rhine’s results in the book Extra-Sensory Perception statistically significant — a figure of 61 percent, where a figure of five percent “would be expected by chance alone,” per the Parapsychological Association — others have noted that replication of the results has been inconsistent at best and “a failure” at worst.

What Do You Believe?

As for what I think? Well, I am either extremely un-psychic, or Zener cards don’t work. I’ve never done especially well on Zener cards tests; indeed, the last time I took one, I scored six — right within the expected range of cards guessed correctly by chance.

Regardless, there’s no denying the legacies both Rhine and Zener have left. Duke University, for example, did actually have a Parapsychology Lab for a number of decades — and although it was originally started in 1919, almost a decade before either Rhine or Zener arrived on campus, its most heavily documented years span from 1930 to 1965 — right when Rhine and Zener were beginning their work with the Zener cards. After Rhine left Duke in 1965, he founded the Foundation for Research on the Nature of Man, which later became the still-operating Rhine Research Center; it’s considered to be the successor to the Duke Parapsychology Lab. Rhine’s book, Extra-Sensory Perception, remains highly cited by those who believe in ESP, and the peer-reviewed journal he established, the Journal of Parapsychology, is still published today. He’s considered to be the founder of parapsychology as we know it, and his influence has spread far and wide.

Zener, meanwhile, distanced himself from the research he and Rhine worked on together, even requesting that Zener cards be renamed ESP cards in order to separate his name from them. He went on to work with Mercedes Gaffron on research surrounding theories of perception and perceptual experience. He also edited three journals over the course of his career: The Journal of Psychology, the Journal of Personality, and Character and Personality. His obituary made no mention of Rhine or the cards that once bore his name.

More broadly, card-guessing is no longer used as a method of research in parapsychology. Still, though — they continue to fascinate us, whether we’re convinced that they work or not.

Want to give Zener cards a shot? It’s easy to do so now; you can find tons of digital versions of the original test online.

How well did you do?

And, more importantly, was it due to chance… or to something else?

You’ll have to decide for yourself.

Good luck.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via Wikimedia Commons (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8), available under the public domain and CC BY-SA 4.0 Creative Commons licenses.]