Previously: The “Cameraheads” Mystery And The Pitfalls Of Internet Preservation.

You wake up. You’re in a room — a room with red walls. And not just any red; the walls are a bold red — crimson, if you will. You are in a Crimson Room. You have no idea how you got there, and the door, when you try it, won’t open. What do you do now? You escape, of course — or at least, you try to escape. That’s the point of the Crimson Room game: It’s a room escape game. Your goal is simply to get out.

This setup will undoubtedly sound familiar to many of you; escape rooms are a proverbial dime a dozen these days — I can name two within walking distance of my own home, and another dozen within extremely easy access. But Crimson Room, along with three other games — Viridian Room, Blue Chamber, and White Chamber — are room escape games of a different sort: Ones you accessed on the internet, rather than in real life, playable directly in your web browser.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

They’re also, in a word, old — about 20 years old, at this point — and unless you’re… let’s call it of a certain age, you might not ever have heard of them, despite how influential they truly are.

Me? I am definitely of a certain age, so Crimson Room and its fellows really hit the nostalgia buttons for me. I played all of them around the time they were released; I have extremely vivid memories of sitting at my desk in one of my first apartments, clicking through each of them with my roommates close by. 20 years is an eternity in internet time, and back then, the internet still felt full of the beauty of possibility, rather than like the, uh, soul-crushing cesspool it has since become. These games exemplified that feeling — the sense that the internet could do some truly wonderful things, that it could give us a venue for immersive experiences and outside-the-box storytelling in ways we hadn’t seen before.

Despite my fondness for Crimson Room, though, I hadn’t thought about it or any of its sequels in years — not until a brief mention of them popped up in something I was skimming earlier this year, and memories of these weird little games came rushing back to me.

And I wondered: What had happened to these games? Were they still around? Could you still play them? What has Crimson Room’s creator been up to in recent years? Was he still making games?

But, y’know, hey — that’s what I do: I dig through weird stuff and try to find the hidden stories underneath. So, I got to searching — and friends, the story of the Crimson Room games is so much richer than I knew.

Strap in, friends. This one is a ride.

What Is Crimson Room?: An Introduction To Escape Rooms In Video Games

First, if you’re not familiar: What is Crimson Room, anyway?

Briefly, Crimson Room and its three follow-ups, Viridian Room, Blue Chamber, and White Chamber, comprise a series of browser-based, Flash Player-powered, point-and-click room escape games created by Toshimitsu Takagi under his Takagism banner in the early-to-mid-2000s.

Wildly popular during the era in which they were released, they’re also very much relics of their time: They were built on a platform long since discontinued, using file formats that are no longer supported; they can only be played today with the help of an emulator; and — perhaps most importantly — the room escape game market has since become so oversaturated with options, both in video games and in real life, that these four little curios are now essentially obsolete.

They also just… don’t hold up particularly well as games by modern standards. The puzzles can be quite obtuse, and with the need to click on one, extremely particular spot on the screen in order to “solve” many of them, it can sometimes feel as though getting through each scenario is more a matter of luck or pixel hunting than it is of logic or smarts.

But: They also occupied a highly specific period in internet history, and would go on to become enormously influential in the development of the room escape game subgenre. For that reason alone, they’re worth looking at.

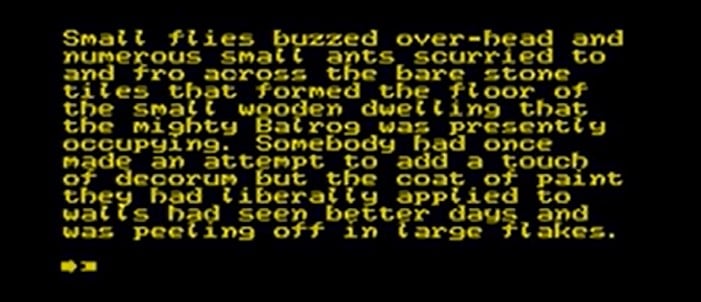

Now, the Crimson Room games weren’t the first room escape video games ever created; that credit usually goes to the 1988 text adventure game Behind Closed Doors, developed by John Wilson. It’s perhaps worth pointing out that elements of these kinds of games were also present in earlier titles, like 1977’s Zork (and, for that matter, most of the other subsequent text adventure games published by Infocom during the 1980s) — but Behind Closed Doors gave us the single-setting, player-is-trapped-in-a-solitary-room-and-must-get-out format that typifies the room escape game subgenre and sets it apart from general narrative puzzle-solving games.

As TV Tropes points out, though, the Takagism games — especially Crimson Room and Viridian Room — codified many of the characteristics and elements that now define a room escape video game: They’re typically first-person; traditionally, they’re point-and-click games, although in recent years, that’s not necessarily a given (the 2022 title Escape Academy, for instance, allows players to move around freely, rather than popping them down in front of static screens and making them click through each of them to change their view); and the puzzles mostly revolve around collecting objects and combining or using them in specific ways to reveal keys and codes that allow you to progress.

The final key is, of course, the one that opens the room’s door — although the “key” isn’t always a literal key, and the “door” isn’t always a literal door.

None of the Takagism room escape games are very long — they can each be completed in a matter of minutes, if you’re really clever — and, with the exception of Viridian Room, there’s basically no plot to speak of. But for the sake of argument, let’s talk details, shall we?

From Room To Room: A Takagism Room Escape Game Primer

As I previously mentioned, there are four Takagism games: Crimson Room, Viridian Room, Blue Chamber, and White Chamber. Not all of them are connected (although some of them are), and on top of their general brevity, some of them are even quicker to solve than others. They do, however, all have the same basic premise at their core: You’re trapped in single room, and you need find your way out by navigating the space, finding objects, and interacting with them or your environment in certain ways.

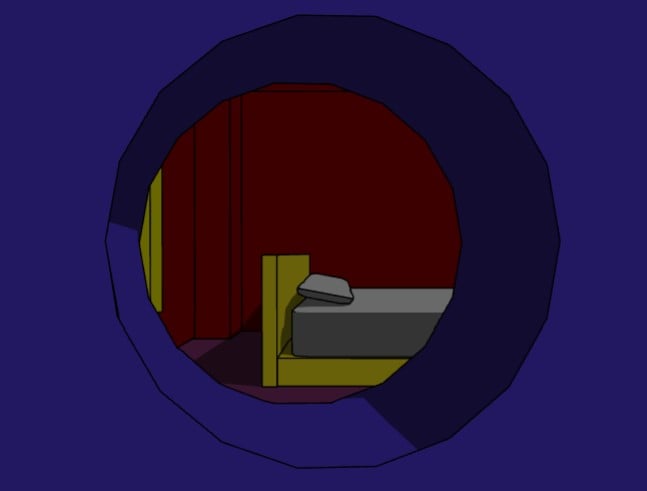

Crimson Room sees you waking up in a strange room, surrounded by red walls, with no memory of how you got there. A brief written prologue tells you that you may have overdone it a little the night before, but you can’t remember anything else. The room itself might be a hotel room — there’s a bed, a dresser, a stereo, and a window with a curtain in there with you, but not much else beyond that — but then again, it might not be; you don’t really know. All you know is that you have to get out.

Viridian Room functions as a direct sequel to Crimson Room. The relationship between the two is initially alluded to by the fact that the one item you pick up in Crimson Room that you never use — an empty CD case — is still in your inventory in Viridian Room; however, it’s made more directly apparent if you look through the empty doorknob hole in one of the room’s two doors: You can see the Crimson Room itself through the hole, meaning this particular door is the one you exit through at the end of Crimson Room.

As for the plot in Viridian Room, insofar as there is one? Well, you discover fairly quickly that there are the remains of another human inside the room with you — just a skeleton, nothing too graphic — and, as you explore the room, you both learn who this other human was, and realize that you must perform a ritual to set their soul free. Doing so will (presumably, at least) allow you to escape the room, as well, although by what mechanism the escape is made is never quite explained. Without giving away too much, the ending is what I might describe as abstract.

We also never learn exactly how or why we ended up in this whole situation in the first place. So, although Viridian Room fleshes out more of a story for both it and its predecessor, it still doesn’t answer most of the questions Crimson Room raises to begin with.

Blue Chamber is perhaps the shortest of the games. It’s also standalone; it has no tangible connection to either Crimson Room or Viridian Room, other than the obvious thematic ones: It’s a room escape game that gets its name from the color of the room from which you’re trying to escape. You’re not told how you got there — or even where “there” is — and there’s no plot or story to this one.

Interestingly, though, Blue Chamber introduces outside characters — ones that, unlike in Viridian Room, are still alive, albeit unseen, and with whom you must communicate in your attempts to get out. The puzzles revolve around two communication tools: A telephone, and a pneumatic tube system.

(I’m a sucker for pneumatic tube systems. Love those things. The thought of physical objects zooming through little tubes on their way to somewhere else entirely to be received at the other end by someone you can’t see is just endlessly amusing to me. I have a particular fondness for Blue Chamber as a result, despite it being pretty bite-sized as an experience.)

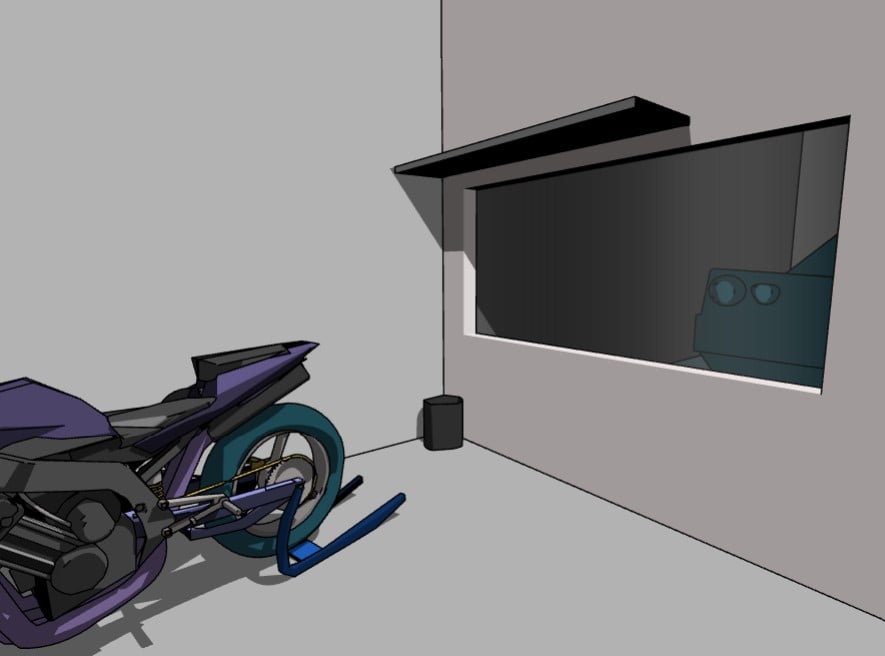

Lastly, there’s White Chamber. This one is a bit of a departure from the previous three games, at least in terms of its setting; instead of being trapped in a room that looks like it could be inside a home or a hotel — that is, a room with furniture like chairs and beds and shelves and dressers — you seem to be in some kind of garage. There’s a motorbike in the room with you, and through a large window in one of the walls, you can see a car.

Like Blue Chamber, White Chamber is also standalone, although you’re given a rough framing of the type we last saw in Crimson Room as well: You were apparently on the road during a snowstorm and you blacked out. When you wake up, you’re in the White Chamber’s garage, and you determine that you need to escape.

At this point, you might be asking, but Lucia, why are you so fascinated by these games? Why are we talking about them here, at TGIMM, where we usually talk about ghost stories, or unsolved mysteries, or urban legends, or dark history? And why, especially, are we talking about them during the Halloween season?

Those are all fair questions. These games are not, after all, horror games — not really (although you could make the argument that Viridian Room flirts with horror, even if it’s not overtly horror). Sure, they’ve got some creepy sound cues and a bit of a weird sensibility, but they’re otherwise fairly conventional puzzle-solving games. We’re not looking at Hotel 626 here, after all.

But they have always felt horror-adjacent to me, and not just because one of them straight-up has a skeleton lying on the floor in the room with you. They’re inscrutable in a way that’s vaguely unsettling, even if it’s difficult to articulate why they feel as such, and the atmosphere that they all plunk us down into is, in a word, eerie.

And, as it turns out, trying to put together the history of the games and their creation is as much of a puzzle as the games themselves are. Here, the mystery deepens and the plot thickens — and uncovering the story of these iconic games and their creator is as rewarding as escaping from the Crimson Room itself.

Humble Beginnings: Toshimitsu Takagi, Takagism, And Early Interactive Online Media

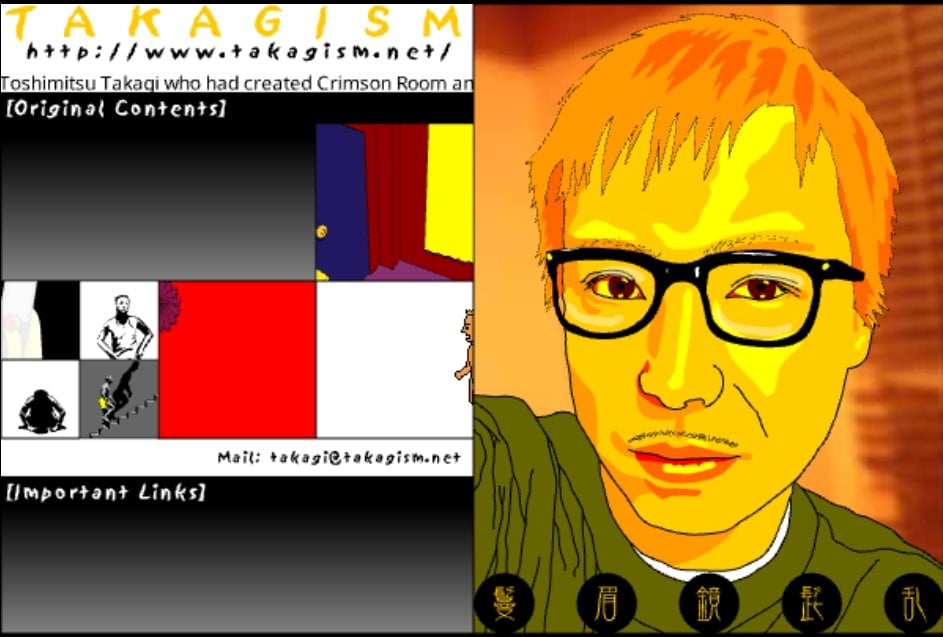

There isn’t a ton of information available about Crimson Room creator Toshimitsu Takagi available online, and what there is, I had to dig pretty deep to find. His online presence has always been fairly scant, and in recent years, it seems he’s cut down on it even further; his Twitter account, for instance, hasn’t posted anything since 2018, and although he also has a YouTube channel, he hasn’t published any videos on it since 2022.

His website, meanwhile — Takagism.net — went down sometime in 2020: Its last operational capture on the Wayback Machine is February of that year, and by June, it was gone completely.

It’s obviously Takagi’s right to exit the internet; honestly, the way things are going these days, he’s probably smart to do so. I bring this up mostly for anyone who’s been curious about what he’s been up to recently, because, well… you might be disappointed, as he’s not really making much — if any — of that public.

After a bit of sleuthing, though, here’s what I’ve been able to put together:

Toshimitsu Takagi (高木敏光) was born in 1965 on Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost island. He left Hokkaido as a young adult to attend Waseda University, whose main campus is located in Tokyo’s Shinjuku ward on the largest island of Honshu; there, he earned his degree in Western art history, after which he returned to Hokkaido.

According to a profile of Takagi that appeared in the Digital Front Line publication of the Computer Graphic Arts Society (CG-ARTS) sometime in the latter half of 2005 (I think, at least — the article references Crimson Room having been live for about a year and a half at the time of publication, which would place it in the fall of 2005), he joined Sapporo-based digital content company DataCraft Co., Ltd. as a copywriter in 1991. He was later seconded to a weather information company located in Chiba City, however — which ultimately became a turning point for him.

During this secondment, Takagi — who had no background in programming or web design — began learning about digital animation and the possibilities computers provided when it came to creating art. Upon beginning the secondment, he told Digital Front Line, the weather information company supplied Takagi with a Macintosh IIfx. Then considered a highly advanced machine, with a sky-high price tag to match, the computer afforded him a substantial amount of learning opportunities.

Said Takagi (via Google Translate):

“Inside [the computer] was a software called Director. At the time, there was only an English manual, so at first, I thought it was an image database. I eventually learned that it had a layer function, and I could use it to create animations. I realized that it could be used to create cel-style animation and feature films! I thought it was a great discovery. From there, I was hooked on Director.”

The Director program Takagi is talking about here is Macromedia Director, previously known as MacroMind Director, and eventually much later as Adobe Director. (Adobe bought Macromedia in 2005 for $3.4 billion.) With its ability to incorporate lots of different file formats — bitmap, audio, and video — along with support for vector graphics and 3D interactivity, it made for a powerful tool for creating animation sequences. If you ever interacted with any early internet media — animation, a browser game, something like that — using Shockwave Player, that media was probably built using Director. By the time the eighth version of Director was released in March of 2000, it could also handle Flash animation files, which by then had become the dominant format for interactive media on the internet. (Raise your hand if you were once a frequent visitor of Newgrounds.)

In any event, Takagi’s interest in digital art and animation continued after he finished his secondment, and he made it a goal to use Director and its assets to make “one movie a day” in order to keep learning. He also began creating games, videos, and other experimental projects — and eventually, out of all of this fascination and learning came Crimson Room.

Going Viral: Crimson Room’s Release, Re-Release, And Runaway Success

It’s hard to find launch dates for most of Takagi’s games and other projects these days, partially because most of the sites at which they were originally hosted are no longer live, and partially because these sites never had a ton of dates on them in the first place. But, from what I’ve been able to piece together, the first version of Crimson Room launched in or around February of 2004 on Takagi’s personal site at DataCraft.

Although you’ll sometimes — often, even — see April 2004 listed as the launch month for Crimson Room, there’s plenty of evidence that the game was actually live a few months earlier. The most important piece is Takagi’s own DataCraft site; the Feb. 12, 2004 Wayback Machine capture of it bears a page title of “CRIMSON ROOM.” (The snapshot of the page itself isn’t viewable in its complete form, unfortunately, but it’s pretty clear that at the time, we would have been able to play Crimson Room right then and there.) Additionally, I found a thread on the online forum WebHosting Talk dated Feb. 17, 2004 that’s full of people discussing Crimson Room, complete with a link to Takagi’s DataCraft site — where the game itself would have been hosted at the time.

According to Digital Front Line, Takagi built the game in about a week: He spent three days modeling; another three were used for scripting; and then, he spent one final day putting the finishing touches on everything. After that, he put it on his DataCraft site, emailed it around to some of his coworkers, and asked them to tell him when they had solved it.

Although the game spent its first week live languishing in obscurity, it went viral — to use the modern parlance, at least; the term “going viral” was still in its infancy then — not too long after that. Soon, it became so popular that the DataCraft server crashed from the traffic the game was receiving. Takagi subsequently moved Crimson Room to its own server — and, eventually, off of DataCraft altogether.

Remember that April 2004 launch date I mentioned earlier? I believe that’s when the server switch happened. The timeline is wibbly and there’s not a lot of solid information available here, but it would make sense if that were the case.

In any event, Takagi left DataCraft not too long after Crimson Room’s runaway success. By the end of 2004, he had departed the company to strike out on his own, continuing to create games, animations, and other experimental content under the banner of his own brand, Takagism. His original DataCraft website closed up shop on Dec. 20, 2004 and began redirecting visitors looking for his work to his new website, Takagism.net. From there, Takagism.net instructed visitors looking specifically for Crimson Room to head to yet another website, FASCO-CSC[dot]com — the place Takagi had moved Crimson Room to after its initial home at DataCraft, which would then go on to host the whole series of color-coded room escape games Takagi subsequently created.

Next Steps: Viridian Room, Blue Chamber, And White Chamber

The first of these follow-up games was Viridian Room, a direct sequel to Crimson Room developed over about a month and a half, according to Digital Front Line. It was published in the spring of 2004 — around April, assuming the month-and-a-half development timeline started after Crimson Room’s original mid-February release. Blue Chamber followed shortly after, arriving in May of 2004.

It’s worth noting that Blue Chamber was initially only available as a bonus for folks who spent actual money on Viridian Room. Now, as far as I know, Viridian Room itself was always free to play — but Takagi also made a premium version of it available for purchase. I’m not actually sure whether the premium version was any different from the free version; I didn’t pay for it at the time, and now it’s obviously no longer an option to do so. It didn’t cost much, though — just 500 yen, which even now is only a few U.S. dollars — and may even have just been a “Hey, we’ve made this game available to play for free, but if you want to help support us, you can toss us a few bucks here” kind of situation.

If you did throw in for Viridian Room, though, you got access to Blue Chamber for those first few months it was live. And if you didn’t pay for it then, you only had to wait a few months for open access to arrive: Blue Chamber hit the web for free on Aug. 30, 2004, according to an announcement on FASCO-CSC made on that date.

At this point, the history of Takagism and its colorful room escape games starts to get a little patchy. Takagi did have plans to keep going with the series; at the time that Blue Chamber became free to play, he announced that he had two further installments, Pink Prison and Tangerine Room, in the works. However, I don’t believe either of these two games was ever actually released, and possibly may never even have been completed. There’s no record of them in playable form on any of the sites Takagi hosted his games — not even when you dig through the sites’ archives via tools like the Wayback Machine. There’s just that one mention of them in the Aug. 30, 2004 FASCO-CSC post.

Indeed, Takagi seemingly spent most of 2005 taking a break from his room escape games. Instead, he put his time towards developing an episodic “comic game series,” as FASCO-CSC put it, called Smile Ninja Picomaru. Four Smile Ninja Picomaru episodes launched between April and July of 2005 before the next — and, as it would turn out to be, the final — Takagism room escape game arrived.

This game wasn’t Pink Prison, however. Nor was it Tangerine Room. Instead, it was titled White Chamber. Takagi published it on Dec. 20, 2005 — more than a year and a half after Blue Room’s original May 2004 release — and then after that?

Nothing.

FASCO-CSC’s servers went down briefly for scheduled maintenance in March of 2006, according to a handful of updates posted to the homepage at that time — but after they were restored… crickets. The website remained dormant for many years, with no further updates made — and eventually, it went down altogether.

No further Takagism room escape games have been released since.

A Blessing And A Curse: The Legacy And Downfall Of Crimson Room

So: What happened? Why did Takagi cease development on his room escape games? That, I can’t answer, although it seems not unlikely that a combination of burnout and wanting or needing to focus his artistic attentions on other projects could have contributed.

It’s also worth noting that Adobe’s acquisition of Macromedia occurred in 2005, right around the time Takagi was developing his games — and not too long after that, technology started to move on. As Richard C. Moss put it at ArsTechnica in his excellent 2020 story chronicling the rise and fall of Flash:

“But for all that market dominance — all that success as a technology — Flash never made the transition from a de-facto standard to an actual one. Gradually, the real Web standards caught up. HTML and CSS got more powerful. Implementations of these and other Web standards like SVG and JavaScript got more consistent between browsers. And over time, Flash lost some of its competitive advantage on the Web.”

Although Adobe attempted to keep Flash chugging along for a time after that, it was a struggle, and by 2011, the company had pretty much given up on it. Flash Player wasn’t totally sunset until the end of 2020, but it was basically a zombie for most of that last decade.

The point is this: The tools and the platform that Takagi used to create Crimson Room and its sequels may have been cutting edge in the early 2000s, but by the mid-to-late 2000s, they no longer were — and, indeed, had started to become liabilities, rather than assets.

Furthermore, the online landscape had started to change, with the characteristics that made browser games popular shifting to an entirely different venue: Smartphones and mobile apps. And although Takagi did dabble briefly in bringing Crimson Room to mobile platforms in the early 2010s (more on that in a bit), the competition there was much steeper, with much more advanced games like The Room, released for iOS in 2012, and Rusty Lake’s Cube Escape series, which began in 2015, dominating the landscape.

And then there’s this: The mid-2000s and early 2010s are also when actual, real-life escape rooms started to appear. What’s typically credited as the very first one — Real Escape Game (リアル脱出ゲーム) — was launched by the Japanese company SCRAP Entertainment in Kyoto in 2007; word spread quickly after that, and within a few years, escape rooms had begun to appear in other countries, including the United States. I played my first escape room in 2014, for instance, and I’ve participated in about a dozen more since then.

SCRAP Entertainment president Takao Kato did note on the company’s website in 2011 that online room escape games as a general concept served as the primary inspiration for that first 2007 Real Escape Game; it therefore seems possible — likely, even — that Crimson Room may have been part of that inspiration. At the time, after all, the Takagism games — along with Mystery Of Time And Space (MOTAS), an episodic online room escape game that began running in 2001 and kept things up until 2008 — would have been at their height in terms of popularity.

And with the ability to play room escape games in real, physical space now not only possible, but steadily growing in accessibility? Well, it’s also conceivable to think that the online point-and-click versions of those kinds of games may just have stopped holding people’s attention in the way they once had. Why do it in a browser window when you could do it real life instead?

It’s an interesting twist: While Crimson Room’s legacy is clear, that legacy may also have been responsible for its own downfall. Without Crimson Room, we probably wouldn’t have mobile games like The Room series or the Rusty Lake games. Without Crimson Room, we probably also wouldn’t have real-life escape rooms. And yet, both of those developments in the landscape of room escape entertainment also rendered their forebear obsolete.

Crimson Room walked so those future experiences could run — but unfortunately, that also means it was soon outstripped and left far, far behind by its successors.

Where Are They Now?: The Current State Of Takagism And Crimson Room

As the years went on after the release of White Chamber, the Takagism games fell prey to link rot and the decay of the early internet. One by one, the original websites that hosted Takagi’s work went offline or changed hands, with pretty much all of them now rendered inaccessible except by archival methods like the Wayback Machine.

The DataCraft site, as I previously noted, was shut down by Takagi himself at the end of 2004 when he left the company. Takagism.net, meanwhile, was originally created in 2004 and began hosting Takagi’s animations and other projects in 2005; however, updates to the site ceased sometime in the first half of 2020, and according to its DNS records (accessed through this tool), the domain was completely dropped in 2021 and its nameservers removed. It remained parked for some time after that.

As of March 2024, visiting the URL brings you not to the parking page, but to a page stating that the domain was no longer available; as such, it’s possible that something is in the works over there, although whether it’s Takagi himself behind or not remains to be seen. (The ownership is obscured in the domain’s WHOIS record, so it’s not clear in whose hands the domain currently sits.)

And what about the FASCO-CSC site? Well, it’s changed hands a few times since it stopped operating as the base for the Takagism games. Its last Wayback Machine capture as a Takagism-associated site is dated Jan. 7, 2012; after that, it 403’d for several years until it reappeared in 2015 under the purview of a Russian domain registration company. It was then parked and the domain marked as for sale. By the early 2020s, it had become a Japanese adult site, which is what it remains today. (So, uh… visit at your own risk.)

There are a couple of other bits and pieces associated with Crimson Room that are worth mentioning here, as well. There was, for instance, a Crimson-Room.com website, although it seems only to have operated as a mobile site (so, technically, it was m.Crimson-Room.com, not just Crimson-Room.com); I believe this site was built specifically to market the no-longer-extant mobile app version of Crimson Room that launched in 2011. The app was titled Crimson Room Eleven, presumably referring to the year it launched. The mobile site was in operation between 2011 and 2016, per its Wayback Machine captures, although it is no longer live today.

Takagi also wrote a tie-in novel for Crimson Room, which he published in 2008. Although it, too, is titled Crimson Room, it seems to be more of a semi-autobiographical story about the creation of the Crimson Room game, rather than a story set within the reality of the game. It’s still described as a “thriller” and a “mystery & detective” novel, though, so do with that what you will. It’s available for purchase via Amazon.jp, although you’ll need to be fluent in Japanese to read it. (I haven’t read it myself, but, y’know, it’s there if you want to check it out.)

And, perhaps most notably — although also most disastrously — an expanded, reimagined version of Crimson Room was developed for PC and released on Steam in 2016. Titled Crimson Room Decade, it definitely takes its cues from the original game; the same basic items are present in the room when you begin, although it all looks much grimier and less modern in style, and many of the early puzzles are beat-for-beat recreations from the source material. It does, however, depart from the OG Crimson Room rather quickly — and not in ways that really make any improvements.

There’s a rather convoluted story to go along with this one. You assume the role of Jean-Jacques Gordot, a French inspector who has been sent to investigate the recently-discovered remains of an ocean liner, La Crimson, which went missing in 1926. Incidentally, you are also a descendent of one Francois Gordot, who was aboard the ship when it went down. Scattered throughout the stateroom you’re investigating are letters and journal entries detailing the plight of the elder Gordot — a sordid tale that seems to have involved Soviet history, and human experimentation, and brainwashing, and a whole bunch of other weirdness. Your goal, as always, is to escape — but, at the same time, it’s also to put together the pieces you find in order to put the bizarre family mystery of what precisely happened to Francois Gordot to rest.

I’ll be honest: It’s… not great. Very little of Crimson Room Decade makes any sense, largely because it falls into the trap of trying to overexplain itself. In some ways, it seems like it’s trying to do what real-life escape rooms do now, with the elaborate backstory, the historical setting, and the addition of multiple environments to solve before you can fully escape; the trouble is, it just… doesn’t work very well. It’s overwrought and confusing, as well as simply unnecessary. I am much more willing to roll with “I have no idea how I got in this room or why I’m trying to get out, but sure, let’s escape” than I am with… whatever is going on in Crimson Room Decade.

The mechanics of the way the game’s physical space works are also at odds with the setup. The backstory we’re given is quite concrete and framed realistically, but the space works functionally by magic. The juxtaposition clashes, rather than gels, and the whole experience ends up feeling nonsensical and arbitrary.

The ending of Crimson Room Decade is reminiscent of Viridian Room’s — which, out of all of the original games, is notably weird and a bit supernatural — but Viridian Room at least is internally consistent with itself; as such, the ending is perhaps odd, but doesn’t feel out of place. Crimson Room Decade, however, has no internal consistency or cohesive reality, so the ending feels like it comes totally out of left field.

Add to that the fact that the game has a price tag of $9.99, but only about 30 minutes of gameplay, and, well… I wouldn’t recommend it. You’re better off playing the original four games, as aggressively mid-2000s as they are.

Playing Crimson Room Now: How To Access The Takigism Games In 2024

But wait! How can you play the original games now, if all of the original websites are offline or no longer functioning? I have good news on that front: A handful of folks have taken it upon themselves to preserve these unique little pieces of internet history — and as long as you don’t mind downloading the Ruffle extension for your browser, you can still play them in all their interactive glory.

The original FASCO-CSC site may no longer exist, but a fan-made recreation of it is available under a slightly different domain: FASCO-CS.net. This recreation was launched around November of 2018, per both its WHOIS record and the date of its first Wayback Machine capture. It’s not run by Takagi — it was put together by someone calling themself CoolJRT, about whom I know absolutely nothing — but it was made using the old FASCO-CSC assets, and it looks just like the old site used to. All four Takagism games are playable at FASCO-CS.net; you’ll just need to download Ruffle, a browser extension that emulates Flash, to experience them. I’ve done it, and in my experience, it works great.

The version of Crimson Room available here, by the way, also makes a slight adjustment to one particular clue — because, in its original form, the game is actually unfinishable.

At one point in the game, you find a note with something written on it that helps you progress. In the launch version of Crimson Room — the February 2004 one — a URL was written on this note; you had to visit the webpage it pointed to in order to retrieve a code needed to continue the game. This URL was part of Takagi’s DataCraft page, though, so once that website went down, that version of the game was rendered unplayable unless you already knew the code.

Now, though, the note just has the code itself written on it. It makes the experience less expansive, perhaps, but since the FASCO-CS.net version of the game is self-contained, it’s also fully solvable again. So, there’s that.

There are also two different versions of each of the four Takagism games available via the Internet Archive: One in Japanese, and one in English. The versions of Crimson Room archived here are the versions containing the note with the URL — which, again, points to a page that’s no longer live. There’s a workaround, though: A snapshot of the page is accessible via the Wayback Machine. I’ll do you a solid and drop the link here. You’ll still have to solve the actual puzzle yourself, but the clue you need is there. You’re welcome.

As for Toshimitsu Takagi himself? As I mentioned, he’s cut down on his online presence in recent years — and although I did manage to unearth one social media account that hints a bit at his current activities, I’m not going to link to it here out of respect for his privacy.

Whatever he’s doing with himself now, I hope he’s enjoying it. And I hope he knows that he holds a special place in the history of the internet.

You wake up.

You’re in a room.

A room with red walls.

A Crimson Room.

You have to escape.

And… go.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Bluesky @GhostMachine13.bsky.social, Twitter @GhostMachine13, and Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And for more games, don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via screenshots/FASCO-CS.net (1-2, 4-6, 9-12); Spectrum Adventurer/YouTube (3); screenshot/Takagism.net (7, 14); Crimson Room Decade (15)]