There are so many things I love about the Halloween season: The cooling weather; the fiery foliage; the sense that, finally, it is socially acceptable for me to watch a horror movie literally every day for two months; and, of course, haunted houses. Or trails, or mazes, or whatever you like to call your favorite haunted attractions. But it’s not just the chance to immerse myself in spooky environments that I love about good old-fashioned haunts (although that’s certainly a big part of the draw); it’s also about tapping into something… bigger. The history of haunted attractions goes back a long way — and even though the adrenaline-pumping experiences we think of as haunts today are fairly recent, they, like so many Halloween traditions, have their roots in something much older.

Like a lot a lot of spooky kids who grow up to be spooky adults, I spent a number of autumns during my childhood building homemade haunts in a friend’s basement — a tradition my pals and I had inherited from our older siblings — and leading any trick-or-treaters who felt up to the challenge through it on Halloween night itself. We had, of course, virtually no budget, but we pushed ourselves to get as creative as we could with the minimal resources we had available to us — and although what we came up with was a far cry from the polished technological marvels on display in the professional haunt industry today, we still managed to fill that basement with screams and shrieks well into the night.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

We were, of course, just one small drop in the vast and spooky ocean of haunters — but we had our place in haunt history, just like every home haunter that came before us, and everyone who would come after us, too.

Here’s a look at where we came from, where we are, and where we might be going in the future.

It’s finally spooky season, after all.

What better way to usher it in?

The Early History Of The Immersive Haunt

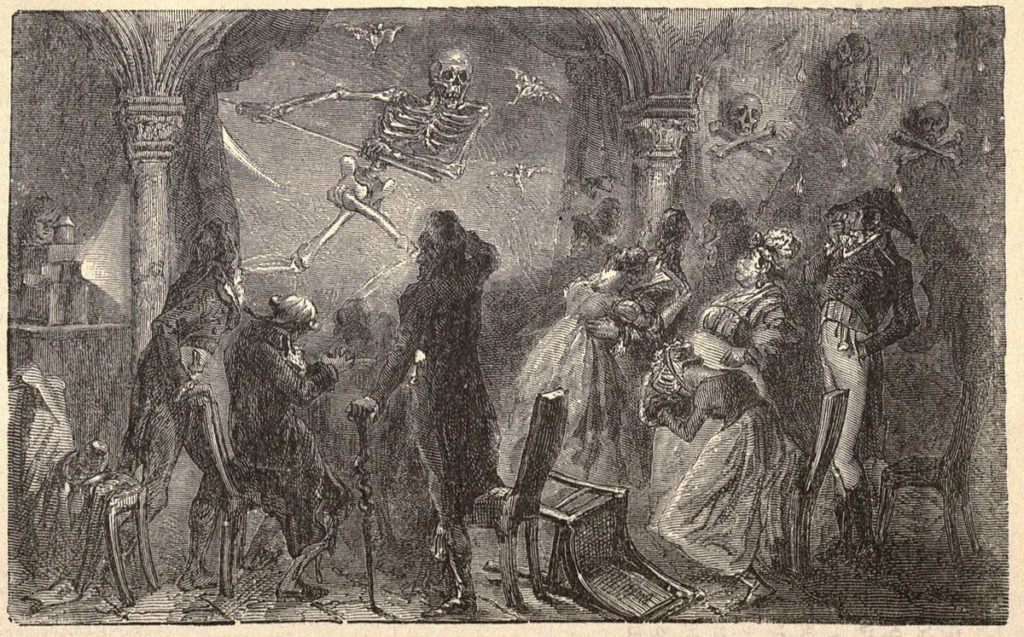

If haunted attractions have always struck you as not dissimilar to immersive theatre, there’s a reason for that: Their closest precursor, was in essence, a piece of live theatre. Phantasmagoria shows, as they were called, used the recently-invented magic lantern, along with other theatrical tricks and techniques, to create elaborate, seemingly supernatural spectacles to frighten and astonish audiences willing to suspend their disbelief.

Although early phantasmagorias first took the stage in Europe in the late 18th century, it was in the early 19th century that they really came into their own. This was thanks largely to developments made by Étienne-Gaspard Robert, the Belgian physicist and showman more commonly known by his stage name, Robertson. In Robertson’s phantasmagoria shows, which utilized an advanced magic lantern he had invented himself called the fantascope, audiences were first ushered into dim, somber settings before given a speech by Robertson setting the scene. After locking the doors and extinguishing the lights, wrote X. Theodore Barber in the journal Film History in 1989, “the audience then heard the noise of rain, thunder, and a funeral bell calling forth the phantoms from their tombs.” Ghostly images projected by Robertson’s fantascope followed, bolstered by appearances of live actors dressed up as ghosts. Throughout the show, a Franklin’s Harmonica produced a chilling soundtrack that also hid the noise of the machinations going on behind the scenes.

At around the same time that the phantasmagoria show was wowing superstitious audiences across Europe (and, later, America), Marie Tussauds — or Madame Tussauds, as you might better know her — had begun exhibiting the impressively lifelike wax sculptures of famous (and infamous) real-life figures she had been making since 1777. Following in the footsteps of her mentor, Philippe Curtius, who had added what he called the Caverne des Grands Voleurs — the Cavern of the Great Thieves, featuring the wax figures of a variety of French criminals, the royal family, and the aristocracy, all of whom had met with a sticky end courtesy of the friendly neighborhood executioner — to his own exhibition in 1782, Tussauds included a “Separate Room” section of her first London exhibition for some of the more gruesome figures in her collection. This “Separate Room,” which was first displayed in 1802, eventually evolved into the walk-through attraction that’s been a mainstay of Madame Tussauds wax museums ever since: The Chamber of Horrors, originally opened in 1835 along with the very first Madame Tussauds wax museum on Baker Street. (The museum was relocated to its current location on Marylebone Road in 1884.)

With the dual popularity of both attractions in which stationary audiences enjoyed immersive “haunted” experiences and attractions in which moving audiences walked through a succession of terrifying (and often gory) scenes, it was only a matter of time before someone combined the two ideas — and that’s exactly what happened around 1915: That’s when wheelwright and coach builder George Orton and woodcarver Charles Spooner, who had partnered up to create fairground rides in 1894, built the Orton and Spooner Haunted Cottage, thus creating the first documented haunted house attraction in history.

Powered by steam, the Haunted Cottage utilized a number of features common to funhouses at the time, including a labyrinthine layout, rocking floors, unexpected blasts of air, and walls that shook. The difference was the theming — and the fact that it all happened in the dark. The attraction traveled fairgrounds throughout the UK and elsewhere in Europe for many years; since 1991, though, though, it’s made its home at Hollycombe Steam In The Country, the collection (Britain’s largest, apparently) of working steam devices located in Hampshire.

But although technology would become a hallmark of the modern haunt, the beginnings of the haunt industry in the United States were much simpler: They started — where else? — at home.

Homegrown Haunts In The United States

In the United States, which also got its fill of phantasmogia shows and funhouses during the 19th century, the nature of Halloween celebrations underwent a bit of shift at the beginning of the 20th century. Mischief-making steadily rose in popularity, with pranks becoming the name of the game As Lisa Morton noted in her excellent book Trick Or Treat: A History Of Halloween, it wasn’t unheard of for turn-of-the-century craft guides geared towards boys to include tips such as the following:

“This is the only evening on which a boy can feel free to play pranks outdoors without danger of being ‘pinched,’ and it is his delight to scare passing pedestrians, ring door-bells, and carry off the neighbors’ gates (after seeing that his own is unhinged and safely placed in the barn). Even if he is suspected, and the next day made to remove the rubbish barricading the doors, lug back the stone carriage step, and climb a tree for the front gate, the punishment is nothing compared with the sport the pranks have furnished him.”

But although some pranks carried out in the name of Halloween merriment were relatively harmless, many others were less so — and, as the 1920s arrived, moved from mischief to straight-up vandalism. By the 1930s — when tensions were already high due to the stresses caused by the Great Depression — things had gotten so bad (think turned-over cars, sawed-off telephone poles, and other such damage) that many cities started to take one of two tacks: Ban Halloween all together — or encourage parents and adults to provide alternative activities to keep kids busy and out of trouble on the night itself.

Many of those alternative activities have gone on to become institutions in their own right: Trick-or-treating, costume parades, and Halloween parties all kicked up in the United States during this period. They were, however, homegrown, rather than the huge blow-outs and sponsored events that became the norm in the latter decades of the 20th century — and so, too, were the haunted attractions that emerged at this time, as well.

Guides for how to create simple home haunts, “house-to-house” parties in which children “could spook themselves by traveling from basement to basement and experiencing different scary scenes,” per Smithsonian Magazine, and “trails of terror” circulated along with other party planning suggestions in the 1930s. One such guide, dated 1937 and highlighted by Lisa Morton in Trick Or Treat, describes the set-up for a potential home haunt as follows:

“An outside entrance leads to a rendezvous with ghosts and witches in the cellar or attic. Hang old fur, strips of raw liver on walls, where one feels his way to dark steps. …Weird moans and howls come from dark corners, damp sponges and hair nets hung from the ceiling touch his face. … Doorways are blockaded so that guests must crawl through a long dark tunnel. … At the end he hears a plaintive ‘meow’ and sees a black cardboard cat outlined in luminous paint.”

But, noted the guide, that was just one possibility; other suggested themes included “Ghouls Gaol,” “Tunnel of Terrors,” “Dead Man’s Gulch,” and “Autopsy.” They were simply executed with whatever the intrepid adult had on hand — not unlike the haunts my friends and would make decades later — but the possibilities were endless; you just needed to get a little creative about it.

And, if you went about it in the right way, it could be a powerful tool for something else: Fundraising.

Fundraisers And The Standardization Of The Haunt

By the late 1950s, many businesses and organizations had realized the potential haunted attractions held as fundraising events. As Noah Wullkotte noted in the exhaustive history of haunts at City Blood, which was originally published in 2017 and receives regular updates, haunts that operated as fundraisers — either for the businesses or organizations themselves, or for causes they supported — during this time include, but are not limited to:

- The San Mateo Haunted House in California, sponsored by the Children’s Health Home Junior Auxiliary, which first opened in 1957 and emerged each Halloween season for 20 years;

- The San Bernardino Assistance League Haunted House, also in California, which originally opened in 1958 and would become sponsored by the Junior Women’s Club in 1960;

- The Children’s Home Society Haunted House, which opened in 1964;

- And the Children’s Museum Haunted House in Indianapolis, which also opened in 1964. Run by the Indianapolis Museum Guild, this haunt still operates seasonally today, making it the oldest, continuously-operating haunted attraction in the country. (Note, though, that the 2020 edition has been cancelled out of safety concerns arising from everything that’s been going on this year.)

There was one organization, however, that really ramped up the fundraising/charity haunt: The United States Junior Chamber, aka the Jaycees. A non-profit leadership training and civic organization, the Jaycees have been in operation since 1915 — and sometime in the 1960s (it’s not totally clear when), individual chapters began putting together Halloween haunts to raise funds. Some of the earliest ones included the Hunting Jaycees Haunted House in Indiana and the Alliance Jaycees and Jay-C-Ettes Haunted House in Ohio, both of which opened in 1967. The Hunting haunt actually still operates today; however, it’s no longer a Jaycees haunt. It’s run under the name Haunted Hotel: 13th Floor.

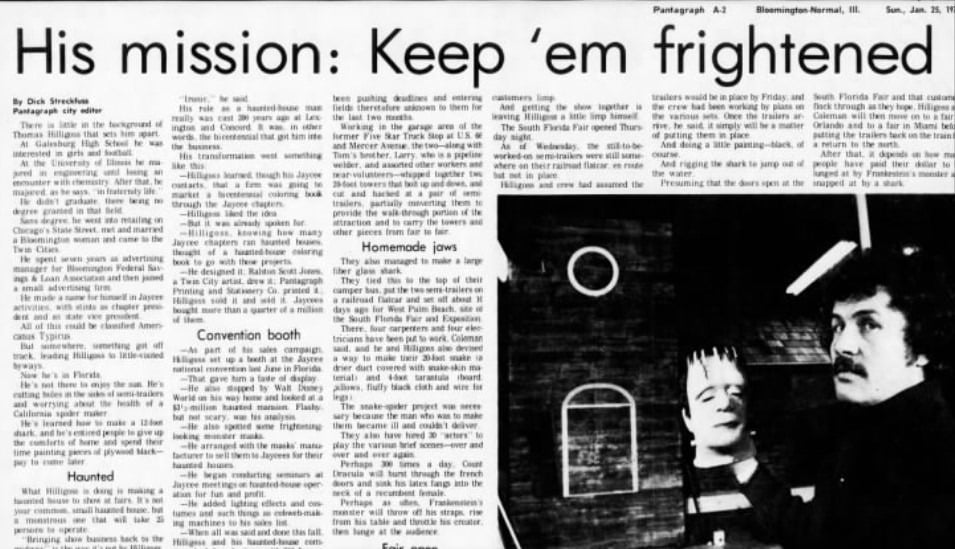

Throughout the ‘70s, Jaycee haunted attractions popped up with increasing frequency, aided by Bloomington, Illinois chapter head Tom Hilligoss. In 1975, Hilligoss wrote a Jaycees-approved manual on how to put together a haunt; then, he began touring the country, giving talks and seminars teaching Jaycee chapters about all the nitty-gritty involved in creating and running a haunt, from construction to makeup application for actors. He conducted these activities under the banner the Haunted House Company.

The Haunted House Company and the Jaycee haunts it taught people to make were, by all accounts, a huge success. As Larry Kirchner, who owns St. Louis high-octane haunt The Darkness and runs the expansive haunted attraction website and database Haunt World, put it to Popular Mechanics in 2016, “When I got started (in the late 1970s), there were, like, 10 Jaycee haunted houses [in every city].” They represent one of the earliest efforts to standardize and professionalize haunts; I’d even go so far as to say that they planted the seeds of what would become the haunt industry as we know it today.

Evangelical Haunts And Hell Houses

While all of this was going on, a particular subset of haunted attraction arose, following a similar template: The evangelical haunt, or what are commonly known as today as “hell houses.”

Although many early haunts mounted by evangelical Christian organizations did end with religious messages or bible study, descriptions of the events themselves suggest that they weren’t necessarily the gruesome showcases of “sinners” getting their “comeuppance” that hell houses are today. Per Noah Wullkotte at City Blood, an experience at Word Of Life Fellowship’s Operation Nightmare event, which ran from 1962 to 1980, went something like this:

“Teenagers would gather together at a parking lot before being transported to an undisclosed location. The bus was escorted by police and would follow an old hearse with a corpse in the back. The hearse would suddenly stop and arrive at a location which was usually in the woods. The students were then escorted in small groups to take a tour of the haunted trail “Nightmare Alley” which included various spooky scenes. They would eventually come face to face with the corpse that was inside the hearse’s casket. After they exited the haunted trail, they joined others to hear the gospel.”

Meanwhile, in 1968, the Campus Life division of Youth for Christ launched the Scream In The Dark program, whose enormously successful events Lisa Morton writes in Trick Or Treat

“combined many of the techniques of the ‘trails of terror’ with heavy amounts of gore and many enthusiastic actors.” Morton further elaborated to the Washington Post in 2019: “I went through one when I was, like, 12, and it was kind of traumatic at that point. You would sit down on a bench to watch an operation, and the bench had actually been wired to give you little electrical zaps.” Those who attended these events would “typically [queue] for one to three hours for an experience that lasted between 15 and 30 minutes.”

The hell house itself, with its emphasis on “sin” and strict, conservative, moralistic (and typically homophobic, transphobic, slut-shame-y, victim-blaming) message, seems to have emerged slightly later. The Liberty University Scaremare event, which was introduced by Jerry Falwell, Sr. in 1972, is usually credited with popularizing hell houses, while Keenan Roberts of Colorado’s New Destiny Christian Center pushed the idea further in the 1990s by selling “ready-to-go hell house kits,” as the Washington Post described them in 2014.

Modern hell houses are fairly insular; they’re also not terribly innovative, largely borrowing their techniques from the haunt industry at whole and repurposing them. But Operation Nightmare and the Campus Life events are notable: As Noah Wullkotte at City Blood put it, “Operation Nightmare’s Nightmare Alley could possibly be the first haunted trail in the United States. … Without Operation Nightmare, the modern-day haunted trail might not exist”; meanwhile, what Lisa Morton writes about the Campus Life events — including the long wait times for a relatively brief experience — sounds quite similar to the way many modern haunts operate.

Mazes And Scare Zones: The Amusement Park Haunt

The 1960s and ‘70s were boom years for haunts, so it should perhaps be unsurprising that yet another advancement occurred during this period, as well: The birth of amusement park haunted events.

When Disneyland’s Haunted Mansion opened in 1969, it had less in common with the walk-through fundraising haunts that had been growing in popularity throughout the previous two decades than it did with carnival dark rides — but it was still a game-changer in terms of how people thought about haunted houses.

I’ll be honest: Although some cite the Haunted Mansion as “the haunt that started it all,” I don’t totally agree with that assessment. Although planning for the ride began in the 1950s — prior, even, to Disneyland’s grand opening in 1955 — the Haunted Mansion didn’t begin welcoming visitors until 1969. By that point, haunted attractions had already begun to pick up a great deal of steam in the United States; indeed, as Theme Park Tourist’s extensive history of the Haunted Mansion notes, the plan for the attraction was “to celebrate the classic Haunted House attractions that were already well-established by the early 1950s” — not the other way around.

Still, though — the Haunted Mansion’s influence on the evolution of haunted attractions can’t be overstated. Trick Or Treat observes that the ride’s “use of startling new technologies and effects” showed what haunts could accomplish if they really pushed the envelope; in fact, notes the book, many contemporary “haunters” point to the Haunted Mansion as one of their primary inspirations.

Besides, it was just a handful of years later that another Southern California theme park launched an event that (eventually) took the walk-through haunt to a whole new level: In 1973, Knott’s Berry Farm held its first Halloween Haunt event — and although this particular event was relatively tame, consisting mainly of a handful of costumed monster roaming the park and some general spooky décor put up throughout the environment and on a handful of rides, it would, in time, grow into Knott’s Scary Farm. The 1977 edition saw the arrival of the event’s first standalone, walk-through maze — and today, Knott’s Scary Farm offers around a dozen highly detailed mazes, numerous scare zones, a variety of shows, and plenty of walk-around characters over the course of about a month and a half between the middle of September and early November.

Universal Studios, of course, would take up the Halloween haunt mantle later on; the first Fright Nights event was held at Universal Studios Orlando in 1991. At the time, it took place over just three nights — but, like Knott’s event, it would grow in scope, with, again, about a dozen mazes, a number of scare zones, walk-around characters, shows, and more. Universal Studios Hollywood, Singapore, and Japan would also eventually begin offering Halloween Horror Nights during the fall — Hollywood sporadically throughout the ‘90s and early 2000s before falling into a more regular, annual pattern, Singapore in 2011, and Japan in 2012.

These days, amusement parks across the United States offer similar Halloween events following the same basic format as that set by Knott’s and, later, Universal — but something else also occurred at an amusement haunted attraction in the meantime that had a huge and lasting effect on the haunt industry: The Six Flags Haunted Castle fire.

The Six Flags Fire And The Rise Of The Modern Haunt Industry

In October of 1979, Six Flags Great Adventure in Jackson Township, New Jersey, leased a walk-through haunted attraction made from a series of trailers from the now-defunct Toms River Haunted House Company. The Haunted Castle wasn’t meant to be a permanent installation; indeed, it was just a temporary attraction intended to help bolster attendance throughout the Halloween season (which, historically, can be slow for amusement parks in geographic areas that experience colder autumns and winters). Its surprising popularity, however, prompted the attraction’s return to the park in subsequent seasons, along with a renovation that lengthened the maze considerably. The Haunted Castle eventually became a permanent attraction, despite the structure still being considered temporary by the township.

But on May 11, 1984, a terrible tragedy occurred: A fire that began in the Haunted Castle resulted in the deaths of eight teenagers.

The aftermath of the fire and the deaths of the teenagers brought about sweeping reform and a dramatic increase in safety regulations for haunted attractions — which, in turn, may have put an end to the homegrown fundraising haunts that had dominated the previous decades. Wrote Chris Heller for Smithsonian Magazine in 2015, “Volunteer organizations struggled to compete against new competition under tougher rules. Soon, many were forced out of business.”

At the same time, others who had seen how popular these haunts had grown and had bigger plans for the idea — and more resources to execute them — which may have been the final nail in the proverbial coffin. Said Larry Kirchner to Smithsonian Mag, “The Jaycees got pushed out because their haunted houses were fairly basic. It was based on the premise that people would volunteer, but when you have people opening big haunted houses with lots of advertising, that’s hard.”

Thus, the haunt industry became… well, the haunt industry. As a result of these changes — and, in recent years, more changes (Popular Mechanics posits that the rise of CGI in the film industry caused special effects artists who worked in practical mediums to look elsewhere to employ their talents, arriving on haunts as a suitable seasonal gig) — the creation and operation of haunted attractions increasingly became the territory of professional haunters, with each year bringing bigger haunts, pricier haunts, and more technologically advanced haunts. By 2013, haunts had become a $300 million industry, according to NBC News.

Even today, though, the modern haunt allows us to see its roots in numerous ways. Some of the biggest, most well-known, and best-funded haunts began essentially as home haunts; Bates Motel in Pennsylvania, for example, began in 1991 as a way for Arasapha Farms to bring in some extra money during the Halloween season, while California’s Pirates of Emerson fright park began in a literal backyard. Fundraising haunts still exist, too; the Indianapolis Children’s Museum haunt is still going strong, for instance, as are some Jaycees-affiliated haunted attractions.

But haunts continue to distinguish themselves in new ways, as well. Some do so by upping the intensity beyond what many would be comfortable with. Some offer other experiences alongside more traditional haunts, such as spooky escape rooms or zombie-themed laser tag. Some are more like pieces of immersive theatre, letting you loose to explore a complete environment and allowing you to make your own story, rather than keeping you on rails the entire time. Some are less immersive and story-driven, more “selfie museum” than a traditional haunt. I’ll be interested to see if any virtual haunts — whatever the phrase “virtual haunt” might mean — pop up this year in lieu of in-person experiences, too.

These days, there are as many ways to haunt as there are people in the world — and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Welcome to the Halloween season.

I’m glad you’re here.

Let’s get spooky.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via Tama66/Pixabay; Wikimedia Commons (1, 2, 3); screenshot/Newspapers.com; Orange County Archives/Flickr, available via a CC BY 2.0 Creative Commons license]

Leave a Reply