Previously: A Ghost Story. A True One.

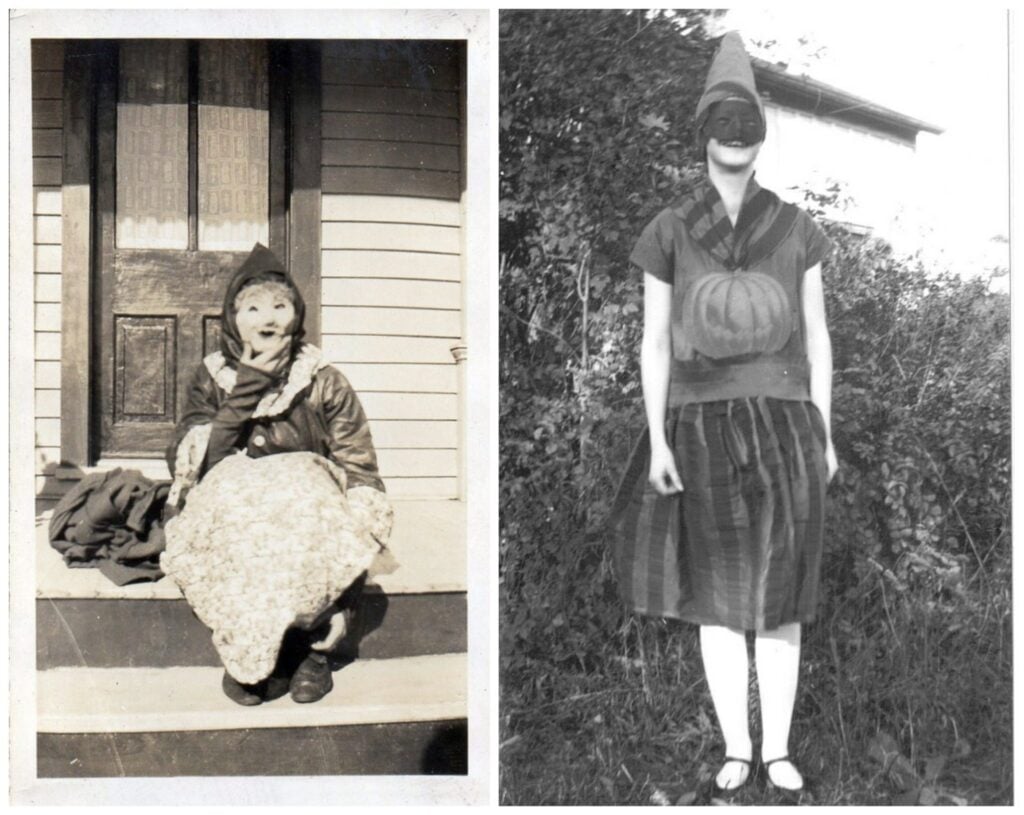

They make the rounds every year: Collections of black-and-white photos — typically depicting children, although the occasional teen or young adult also shows up from time to time — all dressed up in their Halloween best. But the photos are old: Decades old, some perhaps even depicting people who are no longer with us. And with their age comes a peculiar and unique quality — a truth which cannot be denied: Vintage Halloween costumes are straight-up terrifying — even when they’re not meant to be.

I love flipping through these slideshows and scrolling through these lists as much as the next person; indeed, roundups of old school Halloween costumes are one of my favorite parts of Spook Season. What I think these roundups usually miss, though, is an examination of exactly why vintage Halloween costumes are so creepy.

I have some ideas, though. I like to overthink things. Overthinking things is often legitimately my job.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available for purchase now!]

So, hey, if you, too like to overthink things, let’s take a look at one possibility for why Halloween costumes from decades ago send such a shiver down our spines, shall we?

Let’s take a look at the uncanny horror of vintage Halloween costumes. Because if not now, then when?

From Samhain To All Hallow’s Eve

The history of Halloween costumes is as hazy as the history of Halloween itself. Although it’s frequently repeated that Halloween is the modern incarnation of the ancient Celtic festival Samhain, it’s not really quite that simple; Samhain is certainly part of the equation, but Halloween as we know it today is more of an amalgam of many different festivals, observances, and traditions, with a hefty dose of capitalism and commercialism thrown in.

One of the four major observations that delineated the year in Celtic societies, Samhain, of which there are references in literature dating back to the 10th century, marked the end of the harvest season and the beginning of winter. It was when crops were stored. It was when livestock was settled in for the colder months. It was s when the days get shorter and shorter, while the nights get longer and longer. And it was when the veil between this world and the next was believed to be at its thinnest — a time to honor the dead, to pass messages to them, to feed them and to welcome them home through the use of ritual.

Of course, it was also when less friendly spirits than departed relatives were said to wander the earth; care was taken to guard against the faeries, goblins, demons, and other monsters that might be waiting to trick you or take you by surprise.

Christianity later co-opted many Celtic observances — and when it came to Samhain, the feast of All Saints Day in early November was, as folklorist Jack Santino observes in a piece for the American Folklife Center, “meant to substitute for Samhain, to draw the devotion of the Celtic peoples, and, finally, to replace it forever.” It didn’t succeed in this goal, but it did play a key role in Halloween’s development: The night before All Saints Day was referred to as All Hallow’s Eve — the name from which the word “Halloween” arose. The day after, meanwhile, became All Souls Day — a day to celebrate and honor the dead.

Several Roman festivals pre-dating both Samhain and All Saints Day are also sometimes cited as part of Halloween’s roots. The festivals of Feralia and Lemuria — held in February and May, respectively — both honored the dead, although they did it in different ways: Feralia was for honoring your ancestors, while Lemuria was for guarding yourself against dangerous ghosts or spirits — those who may have passed violently or before their times. During Feralia, offerings would be brought the tombs of the deceased, while during Lemuria, the head of the family would perform certain rituals to protect the household against spirits who might otherwise do them harm.

Some sources have also cited a day reportedly honoring Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruit and trees, as yet another part of Halloween’s history; according to these sources, Pomona’s celebration day occurred in late October — around the time during which we now celebrate Halloween — while her symbol, the apple, may account for the incorporation of apples in several Halloween traditions. However, other sources refute this possibility, stating that no evidence supporting the existence of a day honoring Pomona has ever been unearthed.

Trick Or Treat, Trick Or Treat, Give Us Something Good To Eat

Pomona aside, though, costumes factor prominently in a number of Halloween’s precursors: The observances undertaken during Lemuria required special clothing. By the 16th century, Samhain celebrations also included mumming — dressing up as the sorts of creatures said to roam freely during Samhain and performing in exchange for food or drink — which is often cited as one of the origin stories of the practice of trick-or-treating. And All Saints Day incorporated the tradition of dressing up by having participants take on the guise of saints, angels, and devils.

What’s more, costumes are also deeply embedded within some of the other traditions from which trick-or-treating eventually emerged — namely “souling” and “guising,” practices which date back to the Middle Ages in Britain, Ireland, and Scotland. Part of All Souls Day’s celebration of the dead, “souling” involved children going door to door begging for apples, nuts, soul cakes, and other foodstuffs in exchange for praying for the deceased relatives of those who gifted them these items. “Guising,” meanwhile, later arose out of “souling” roughly around the 16th century — and although it consisted of pretty much the same activities as “souling,” this time, they were undertaken in costume.

Trick-or-treating started to become A Thing in North America in the early 20th century, growing leaps and bounds between the 1920s and 1950s — and with it, the Halloween costume as we know it today emerged. Indeed, that’s also the time that companies specializing in Halloween costumes began selling their wares to children specifically for the purposes of the spooky celebration. Flag-making companies Collegeville Flag and Manufacturing Company and H. Halpern Company began manufacturing Halloween costumes in the 1920s, while theatrical designer Ben Cooper branched out into the Halloween costume market with a license for Disney characters in 1937. Together, these costume manufacturers became the Big Three of Halloween disguises.

But although costumes became commercialized around the 1920s and ‘30s, it’s worth noting that the Great Depression also occurred during that time: Between 1929 and 1939, the world suffered one of the greatest economic downturns in history. As such, even though costumes may have been available to purchase, many people didn’t have the means to purchase them. Homemade costumes put together using items you’ve already got and a little ingenuity, however? Those could be fairly easily accomplished — and if it helped get a little more use out of, say, a piece of clothing that might otherwise be too worn to use as actual clothing, so much the better.

By the 1950s, Halloween costumes from the Big Three were being widely sold at retailers like J.C. Penny, Woolworth’s, and five and dime stores — and as the decades went on, and the commercialization of the holiday ramped up, costumes from both these companies and others evolved. These days, the trend is toward costumes with a degree of detail on par with big budget Hollywood movie productions — but there’s something about the simpler, homegrown Halloween costumes of yore that scare the pants off of people in the way that no film-accurate Pennywise costume ever can.

Costumes, Dress-Up, And The Familiar Made Strange

I bring up the concept of uncanniness a lot here at TGIMM, mostly because personally, I find the phenomenon fascinating: Uncanniness will always be freakier to me than any amount of, say, blood or gore. And uncanniness is exactly what I think is at play when it comes to how unsettled simply looking at pictures of old Halloween costumes can make us feel. These costumes aren’t necessarily scary, even though some of them are meant to be just that; but they certainly aren’t cute, either — not in the way we usually think of kids running around pretending to be dinosaurs or witches or superheroes as.

They’re kind of… weird.

Odd.

Unusual.

They don’t look… quite right.

They are, in a word, uncanny.

There’s some pretty in-depth discussion of uncanniness as defined by Freud here and here, so I’ll send you over there for the details (particularly the piece on Hi I’m Mary Mary) — but to recap quickly, Freud identified the uncanny in a 1919 essay as “that class of the terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar.” Something that is uncanny, therefore, is usually described in Freudian terms as “the familiar made strange”: It’s something we know, but which doesn’t look quite right. Even something that’s just the tiniest bit off can inspire feelings of uncanniness — and that, I would argue, is one of the most interesting forms of horror there is.

[For some excellent photo galleries of vintage Halloween costumes, head to Imgur; a handful can be seen here, here, and here.]

In any event, I think this concept applies to vintage Halloween costumes in a few different ways. First, there’s the way it works with regards to pretty much all costumes, whether they’re vintage or not: They take something familiar — a human — and making them strange (that is, they appear as something human-shaped, but not necessarily human: A monster, a skeleton, whatever). This same principle operates on a different level when you see someone in a costume who you actually know in real life: The costume takes your friend and turns them into someone who’s a stranger to you.

But that explanation is admittedly less interesting to me, mostly because it just deals with the idea of Halloween costumes more generally — that is, it’s not specific to vintage-era costumes. The homegrown nature of old school Halloween costumes also has the advantage when it comes to uncanniness of using repurposed materials: Old sheets and discarded pillow cases; paper bags and cardboard boxes; brooms that are too beat-up to do their jobs; clothing that no longer fits properly or which is otherwise distressed or threadbare; that kind of thing. Again, we see items we know — but not in the context in which they usually appear, or in the way in which we’re used to seeing them used. The items are familiar; that they’re parts of costumes make them strange.

And then there are the costumes themselves. Unlike today’s costumes, they’re not necessarily realistic or lifelike: Bears don’t look like bears, pumpkins don’t look like pumpkins, and dolls don’t look like dolls; they look like not-bears, not-pumpkins, and not-dolls. They look both like the humans wearing the costumes and the things the humans are supposed to be, but also like neither — all at once. Everything about it is weird and unsettling.

Even characters with which we’re familiar don’t look quite right to our modern eye. Take the costumes of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck in the last photo of this slideshow, for example (click the arrow on the right to scroll to the photograph in question):

They don’t at all resemble the character designs Mickey and Donald sport these days — the ones we’re used to seeing virtually everywhere, every day, thanks to Disney’s dominance in a huge array of entertainment fields. Here, the designs are older, and although the masks are clearly store-bought (likely from Ben Cooper’s line of licensed Disney costumes), the rest of the costumes are simply assembled from everyday clothing. The combination of all of these elements come together to make something that, to today’s audiences, come across not as cute, as we’d expect a Disney costume to look, but terrifying — like something out of “Abandoned by Disney” or “Grad Night In The Haunted Mansion.”

We Are The Weirdos, Mister

Uncanniness, by the way, is also why horror movie villains look so freaky; again, it’s about the repurposing and recontextualization of items with which we’re otherwise familiar: Hockey masks, Halloween costumes, even William Shatner’s face. I do think, though, that the character of Sam in Trick ‘r Treat is a particularly interesting case; unlike Jason or Pamela Voorhees or Michael Myers, who are both (ostensibly) human and get their uncanniness from the various props that make up their costumes, Sam — even though he looks like a kid in a Halloween costume — isn’t human. His costume does, of course, provide a bit of uncanniness — like Jason prior to the donning of his now-infamous hockey mask, Sam’s mask is a burlap sack (e.g. it’s a familiar item put to an unfamiliar use) — but he’s also uncanny himself. He looks childlike, but he has abilities no child has — and the one time his mask is removed, we learn very quickly that Sam is no child. He looks a little like a sentient jack o’lantern — but ultimately, what Sam is, really… is the spirit of Halloween.

And so, too, I would argue are these ancient Halloween costumes — the Halloween costumes of 50, 60, 70, 100 years ago. They’re spooky and they’re creepy — but they’re also playful, reveling in the joys of pretending to be someone you’re not as you go from door to door in search of sweet treats or clever trickery. They’re the delightful frisson you experience when you hear a good ghost story. They’re the shiver you feel run down your spine when your back faces the cold and chilly night, even as the bonfire before you warms your face. They’re what you aren’t, or what you wish you were, or what you know you could be, given the chance.

They’re weird. But that’s okay. Because this is the time of year when weirdness reigns supreme.

This, as they say, is Halloween.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via Dlila, rich701 (1, 2), simpleinsomnia (1, 2)/Flickr, available under a CC BY 2.0 Creative Commons license; Imgur (1, 2, 3); Wikimedia Commons, available under the public domain.]