Previously: Who Was The Poe Toaster?

What would you do if, one day, you were suddenly approached by two seemingly lost children? Would you try to find out from them information that might help reunite them with their family or carers? Where they were from, for instance? What their home was like? Who their parents were? Would you start making phone calls, reach out to community resources, or take to social media? Would you bring them home in the meantime, and try to feed them and otherwise make them comfortable?

But also: What if they were green? I mean literally green — as in, you were approached by a pair of green children, wandering around your town unattended. What then?

That’s what happened in the English village of Woolpit in the 12th century — or at least, that’s what a handful of written accounts from the time state: That the Green Children of Woolpit, as they came to be known, arrived from somewhere out in the wilderness near the village, dressed in unusual garments and with their skin tinted faintly green. No one knew who they were, or where they had come from — or why, precisely they were so green.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

They said they came from a place no one in Woolpit had ever heard of — perhaps a fairyland; perhaps the moon. Were they changelings? Aliens? And why would they eat nothing but beans?

The Green Children of Woolpit and their strange appearance are regarded even now, centuries later, as one of history’s strangest mysteries — although the precise mystery surrounding the Green Children may not be exactly what you think it is. The mystery isn’t quite who or what these curious young people were; it’s about what the story itself really is:

Is the tale of the Green Children of Woolpit a piece of folklore — that is, a fictional fantasy? Or is it a distorted retelling of factual events?

We still don’t really know — and, as is often the case, we likely never will.

But there’s a case to be made for both angles, and they both remain — again, as is often the case — infinitely fascinating. So: Let’s take a look, shall we? You can decide for yourself on which side you fall.

From St. Martin’s Land To Woolpit: The Green Children And Their Journey

The story usually goes a little something like this:

In the 12th century — the precise year isn’t always given, although it’s sometimes identified as around 1150, or even simply during the reign of King Stephen, which occurred between 1135 and 1154 — the population of the English village of Woolpit awoke to a curious sight: That of two children standing near the wolf pits — or, in the Old English, wulf-pytts — that gave the village its name.

This in and of itself was odd. Wolf pits — traps intended to ensnare wild animals, in this case for the purposes of both hunting and protection — are typically quite large and deep, measuring several meters by all dimensions; and yet, the children seemed to have risen out of one such pit. Precisely how a pair of small children would have been able to scramble out of a deep pit at least twice their own heights on their own was a question with seemingly no answer.

But odder still was this: The children were green. Not the kind of green achieved by painting oneself with dye, nor the kind achieved by simply dressing in green vestments (although it should be noted that their clothing was, apparently, “of unusual color and unknown material,” according to one account). No, these children were actually green, their skin tinged the color of fresh leaves and growing plants.

The villagers did what any well-meaning community would: They took the children in. But caring for them was rough going. A boy and a girl — siblings, it was later determined — they spoke a language unknown to the citizens of Woolpit, and for several days, they refused all offers of food. When they did eventually accept something to eat, they would at first consume only broad beans or fava beans — and only if they were raw, at that.

Slowly, though, the children began to assimilate. They broadened their diet, and as they did so, their skin began to lose the pale green tint the villagers had found so surprising. They also learned to speak English — and once they had a strong enough grasp on the language, they told the villagers their story.

They had come from a place they called St. Martin’s Land, a realm where it was always twilight, and where everything was green. They were not entirely sure how they had traversed from St. Martin’s Land to Suffolk, where Woolpit lay; according to one account, they were startled by a loud noise while they were herding their father’s cattle, and then suddenly discovered themselves to be in Woolpit, while according to another, the cattle had led them into a cavern, at which point they became lost, and emerged into Woolpit by following the sound of bells out from the cavern.

But regardless, both accounts note that the children had also stated that, at home in St. Martin’s Land, there was a river across which they could see a “luminous country.” Whether the land was Woolpit, and whether the luminosity was from the presence of the sun which was lacking in their own land, remains to be seen.

The decisions was eventually made to baptize the children (this was post-Norman Conquest, after all; at the time, Woolpit was under an Anglo-Norman bishop, Walter de Coutances). Unfortunately, only one of them survived long enough to undergo the process. The boy, who seemed to be younger than the girl, was sickly, and did not improve as the days passed. He died before the baptism could take place.

The girl, however, both survived and fully assimilated into the world and culture in which she had landed. It’s said that she worked as a servant in the household of Richard de Calne, to whose manor she and her brother had originally been taken when they were first discovered, for many years; later, she married, and lived out the rest of her days with her spouse in what is now King’s Lynn, about 75 kilometers (roughly 45 miles) north of Woolpit.

All’s well that ends well, it seems… except for the fact that the whole thing is just so weird.

Which, perhaps, is why, even now, we still can’t get enough of it.

And that weirdness? It goes all the way back to the earliest records we have of the incident.

What We Know About The Green Children, And Why We Know It

The complicated nature of the story of the Green Children of Woolpit and its potential veracity or lack thereof starts right at the source — or, rather, sources: There are two contemporaneous accounts of the incident — but two is, uh, not a large number, and even then, calling them “contemporaneous” is… a stretch.

The two accounts both come from historians working within church environments: William of Newburgh, an Augustinian canon — canons, also known as canons regular, being priests who live together in a community under a particular rule, typically organized into religious orders; Augustinian canons were first religious order in the Roman Catholic church to “combine clerical status with a full common life,” per Britannica — born in 1136 who lived at Newburgh Priory until his death in 1198; and Ralph of Coggeshall, a monk and later the sixth abbot of the Cistercian abbey of Coggeshall who died sometime after 1227. And while it’s true that both of them were alive and writing at around the time of the Green Children’s appearance, neither of them experienced the events first-hand.

William of Newburgh’s account appears in the 27th chapter of the first volume of his Historia rerum Anglicarum — or, translated into English, the History of English Affairs. Written between 1196 and 1198 (yes, he finished it pretty much right before he died), it covers the history of England from the year of the Norman Conquest in 1066 through what was then the present for him.

His chapter on the Green Children, titled just straight-up, “On the Green Children,” includes the detail of the events having occurred “during the reign of King Stephen,” as well as the version of the children’s origin story in which they simply found themselves to have been transported to Woolpit while herding cattle. William of Newburgh also states that the boy did survive long enough to receive the baptism, but died shortly thereafter.

Ralph of Coggeshall, meanwhile, recorded his account in the Chronicon Anglicanum, a collection of texts begun at Coggeshall Abbey prior to Ralph’s own arrival, but which he took up and contributed to later on. The Chronicon Anglicanum as it existed before Ralph’s additions began in the year 1066 — again, the year of the Norman Conquest — while Ralph covered the years 1187 to 1224. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ralph-of-Coggeshall The chapter regarding the Green Children is titled, “De quodam puero et puella de terra emergentibus,” or “Of a certain boy and girl emerging from the earth.”

Ralph’s version put a bit more focus on the girl than on the boy; according to his account, it was only the girl who learned to speak English, and therefore only the girl who was able to tell the villagers of Woolpit about the land from which she and her sibling had come. This account also features the story about the children following the cattle into a cavern and finding their way out — and subsequently into Woolpit — by following the sound of a bell.

Here’s the thing, though: Although both of these accounts were written the closest to the time at which the incident with the Green Children is said to have occurred, it’s still difficult to consider them contemporaneous.

Regarding William of Newburgh’s account: Assuming that the Green Children did, in fact, appear during the reign of King Stephen, William would have definitely been alive at the time of the events; whether or not he would have been a functional adult is up for debate, but you’ll recall that he was born in 1136, while King Stephen’s reign began in 1135, with the Green Children reportedly having appeared around 1150 — that is, towards the end of the King Stephen era.

However, note that, given the years in which he was writing the Historia rerum Anglicarum, the Green Children events were already many decades in the past. What’s more, Newburgh Priory, where William lived and worked, is in Yorkshire, some 350 kilometers (about 215 miles) away from Woolpit — quite far, indeed, particularly given the available modes of transportation in the 12th century. He also doesn’t name any of his sources — which, although common for the time, makes it difficult to assess the account’s relative veracity, let alone how contemporaneous we can really consider it to be in relation to the events themselves.

Ralph of Coggeshall, on the other hand, lived much closer to Woolpit — Coggeshall is only about 60 kilometers or just shy of 40 miles away — and does name a direct source: Richard de Calne, to whose manor the children are said to have been brought and in whose household the girl is said to have worked until she married and moved away.

But if William of Newburgh can only be considered contemporaneous at a stretch due to the timeframe in which he was writing — some 40 years after the Green Children reportedly appeared — then Ralph of Coggeshall’s timeframe is even more of a stretch: He didn’t record his chronicle of the Green Children until the 1220s, putting the writing of his account around 70 years after the events reportedly occurred.

All of this is why I hesitate to refer to these two accounts as truly contemporaneous: I think they’re just a little too far removed to be considered as such. But, they absolutely do form the basis for all versions of the story of the Green Children that follow; plus, the fact that they are just a little bit removed is fodder both for the theory that the story is just a story, and for the theory that they’re both garbled accounts of something that did actually happen.

The Green Children As Folklore

There’s a longstanding tradition of dismissing the Green Children story as fictional — and often laughably so, as 16th-17th century historian and antiquarian William Camden did in his most notable work, Britannia, which was initially published in Latin in 1586.

In the section on Suffolk, Camden writes of the “Market-town” of “Wulpett” — that is, Woolpit — and mentions William of Newburgh’s account of “how two little green boys, born of Satyrs, after a long tedious wandering through subterraneous Caverns from another world, i.e. the Antipodes, and the Land of St. Martin, came up here.” Camden declines to elaborate further, however, telling readers that if they would like to have “more particulars of the story,” they’re best off referring to William’s account themselves — which, writes Camden, “will make you split your sides with laughing.”

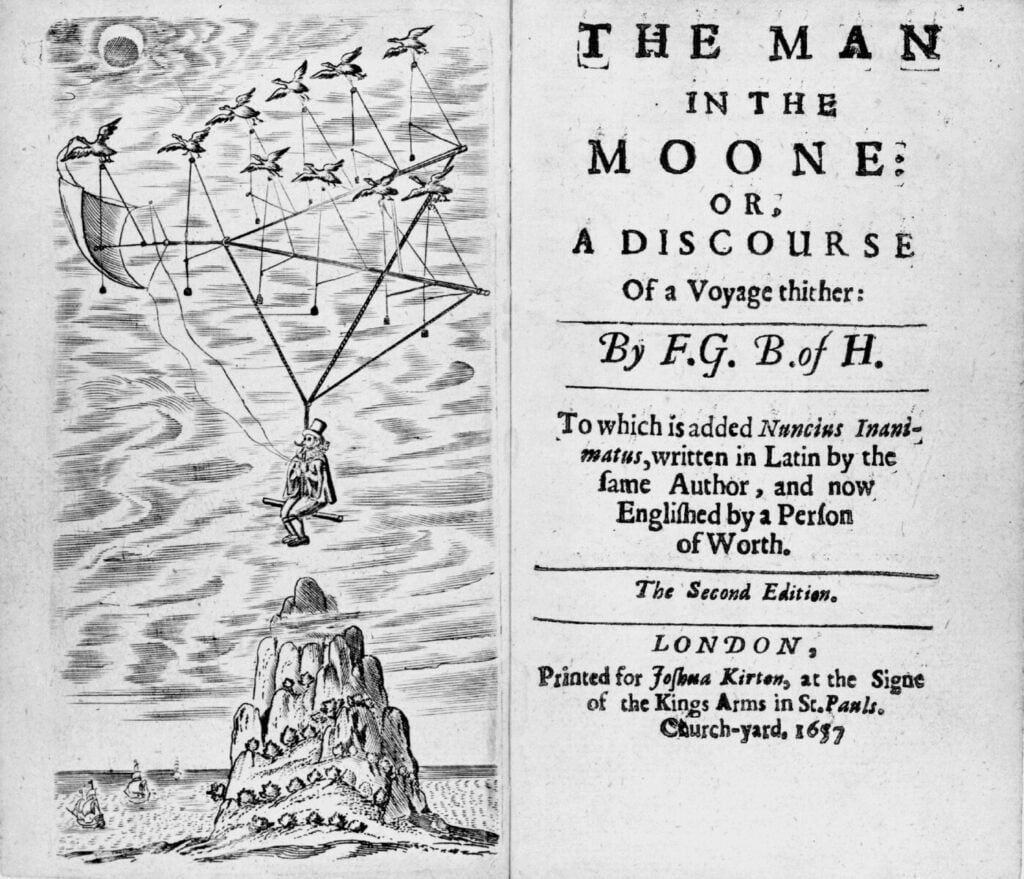

Bishop of Hereford Francis Godwin later used the story of the Green Children as fodder for what’s now acknowledged as one of the earliest works of speculative fiction. First published in 163 (although it was probably written in the late 1620s ), The Man In The Moon: Or A Discourse Of A Voyage Thither tells of a Spaniard, Domingo Gonsales, who travels to the moon and there meets the moon’s inhabitants, the Lunars.

Among the Lunars’ customs, Gonsales learns, is the way they handle children “who are likely to be of a wicked or imperfect disposition”: They exile them to Earth, swapping the miscreant Lunar children for seemingly more well-behaved Earth children, with Godwin putting an extraterrestrial spin on what’s otherwise a classic changeling story.

Typically, the Lunars tell Gonsales within The Man In The Moon’s narrative, they perform this swap in North America, although occasionally they “mistake their aime” and end up swapping Lunar children with Earth children on other continents — including “Christendom,” or Europe.

Then, Gonsales tells us:

“I remember some years since, that I read certain stories tending to the confirmation of these things delivered by these Lunars, as especially one Chapter of Guil. Neubrigensis, de reb. Angl. it is towards the end of his first book, but the chapter I cannot particularly resign.”

Guil. Neubrigensis, de reb. Angl. is William of Newburgh’s Historia rerum Anglicarum, and the chapter towards the end of the first book is Chapter 27 — that is, here, Gonsales directly references the Green Children of Woolpit, describing them as Lunar children who had been sent to Earth due to their “wicked and imperfect dispositions.”

Of course, the recorded “facts” of the Green Children of Woolpit’s story lack the swap that would make the children into changelings: No mortal children went missing when the Green Children appeared; nor do they appear to have taken the places of any of Woolpit’s own children. And yet, it’s not unreasonable to make that classic folkloric connection, as Godwin did — and although Godwin’s work is, and always has been intended to be, a work of fiction (the first edition includes the remark that the work to follow is “an essay of Fancy”), he’s not the only one to have made such a connection.

Indeed, it’s hard to miss all the elements of the Green Children story that line up with tropes and themes commonly seen in fairy tales and folklore — something that a number of writers, thinkers, and scholars have pointed out, particularly in 20th and 21st century analyses of the tale.

As John Clark noted in his article “Small Vulnerable ETs: The Green Children of Woolpit,” published in the journal Science Fiction Studies in 2006, translator, author, and poet Kevin Crossley-Holland presents the tale as much older than even William of Newburgh’s or Ralph of Coggeshall’s accounts position it — so old that, “for hundreds of years before that, it was passed by word of mouth from grandfather to father to son—and no one could say how, or where, it all began.”

Clark also highlights literary critic and novelist Herbert Read’s analysis of the story’s style and form as being indicative of the Green Children being folklore, rather than fact. As in traditional storytelling, Read states (via Clark) that the tale of the Green Children carries “a clear objective narrative … encumbered with odd inconsequential but startlingly vivid and concrete details.” (Read later wrote a novel based on the Green Children story; published in 1935, it was called, fittingly, The Green Child.)

Others, as Clark notes, point to the children’s refusal to eat anything but beans as a hallmark of the story’s folkloric grounding — beans being “fairy food.” Think Jack and the Beanstalk, although it’s absolutely worth noting that Jack as a folk hero and stock character didn’t appear in print until many centuries after the Green Children incident is said to have occurred.

It has also been suggested that the Green Children tale follows the structure of a “Babes In The Wood” story — although, like the connection between fairies and beans, the first known published version of “The Babes in The Wood” didn’t appear until 1595, several centuries after the Green Children’s alleged appearance.

Traditional English “Babes In The Wood” tales detail the tragedy of two children who are left in the care of a relative following the deaths of their parents. The relative, however, attempts to get rid of the children by in the hopes of stealing their inheritance, either by passing them off to a pair of murderers or simply abandoning them in the woods. Regardless, the children eventually end up alone, wandering the woods in which they have been left until they die.

The Green Children incident, of course, has a much happier ending than a traditional “Babes In The Wood” story, although both stories do contain the common trope of wandering children in an unfamiliar environment. We’ll come back to this connection in a little bit — because there might be a factual element to it, as well.

Which brings us to the next possibility: That the Green Children incident actually did happen, although not necessarily in the manner in which the two original accounts describe.

The Green Children As Garbled Fact

A handful of theories have been floated over the years regarding potential real events that could have, in fact, occurred in Woolpit at the time of the reported Green Children incident — but which were misunderstood, or perhaps recorded in a distorted or garbled fashion.

For instance, in “The Green Children of Woolpit: A 12th Century Mystery and Its Possible Solution,” published in 1998 in the now-defunct journal Fortean Studies, Paul Harris argues that the Green Children could have been the children of a family of Flemish immigrants who had become lost; a large wave of Flemish immigration occurred in the early 12th century, and (depressingly predictably) anti-Flemish sentiment rose in England as a result—meaning it wouldn’t be unreasonable to think that the children had been separated from their family due to xenophobia-fueled violence.

Harris also proposes that the seemingly fantastical “St. Martin’s Land” of which the children spoke could simply have been a village not too far away from Woolpit called Fornham St. Martin. And lastly, Harris offers an explanation of why the children’s clothing was perceived as it was: The Flemish style would have been unfamiliar to the English villagers of Woolpit — hence its description as “of unusual color and unknown material,” per William of Newburgh’s account.

Meanwhile, in the chapter “The Colour Green” of the 1997 book A Companion To The Gawain-Poet — an anthology of scholarly essays on the medieval poems Pearl, Cleanness, Patience, and Sir Gawain And The Green Knight — Derek Brewer argues not that the children were Flemish specifically, but rather simply children living in a nearby forest village who had wandered too far astray and become lost. Their trouble getting home was due to the fact that —“in modern terms,” as Brewer puts it — they “did not know their own home address.”

Brewer further posits that the Green Children’s unusual coloration could have been due to “chlorosis,” also sometimes referred to as “the green sickness,” due to the greenish tint that the skin of those with the condition occasionally took on. (I should point out here that Paul Harris also puts forth the “chlorosis” explanation, although I believe Brewer made the argument first. Just, y’know, FYI.)

First described in the 16th century by physician Johannes Lange, “chlorosis” was initially thought of an “hysteric” illness that affected only women (see also: The Yellow Wallpaper and the historic awfulness of women’s healthcare); these days, though, we (thankfully) know better. Now usually referred to as hypochromic anemia, “green sickness” is typically understood to be a symptom of iron deficiency; the unusual skin coloration is due to an insufficient amount of hemoglobin being present in the patient’s red blood cells. (It, uh, should probably also go without saying that it can affect anyone, not just “hysterical women.”)

Another proposal theorizing about the Green Children’s coloration, however, is a bit more violent: Arsenic poisoning. Interestingly, this theory connects the Green Children incident back to the “Babes In The Wood” tale; per the poisoning theory, the Green Children are supposed to have been dosed with arsenic by a nefarious relative, who then abandoned them in the woods near Woolpit to die. It was only by chance that they stumbled into the wolf pit, and were subsequently discovered by the villagers.

One of the symptoms of arsenic poisoning is changes in the skin’s pigmentation — and although these changes don’t typically include the skin turning green, remember that we are looking at these possible explanations for the Green Children incident as things that could have been misunderstood or otherwise distorted in the recording or telling of the tale.

Is it a bit of a jump to go from “skin pigmentation changes as a result of arsenic poisoning” to “kids with green skin”? Yes. Is it still conceivable that the villagers could have made that jump, especially in the context of 12th century medical knowledge? Also yes.

The State Of Things

So which is it? Folklore? Fact? Perhaps a bit of both?

Maddeningly, this remains one of those mysteries which we may never truly solve. Scholarship has gone back and forth on the matter for years, and will undoubtedly continue to do so.

For me personally, although I find the idea of the Green Children story being a garbled or distorted report of actual events, I’ll admit that I’m not fully convinced by any of the specific scenarios that have been proposed over the years. As such, I suppose I stand more on the side of folklore — but even then, things are a bit… wibbly.

Then again, it’s also perhaps worth noting that some, like historian Nancy Partner, consider the debate about what precisely the Green Children story is not to be entirely useful in the first place.

As Partner writes in 1977’s Serious Entertainments: The Writing Of History In Twelfth-Century England:

“I again want to admit quite fully and frankly that I consider the process of worrying over the suggestive details of these wonderfully pointless miracles in an effort to find natural or psychological explanations of what ‘really,’ if anything, happened, to be useless to the study of William of Newburgh or, for that matter, of the Middle Ages. Being convinced that the twelfth-century scholar did make use of the best critical methods available to him—and that is where the real point of discrimination lies — I simply, and at the risk of being accused of a different kind of credulity, accept whatever he accepted as the subject at hand.”

In other words: We can’t bend the sources to say or be what we want them to be; we have to meet them where they are — and that requires taking the writers at their word. They way they recorded the events is the way they perceived them — and that’s all we can work with, because we can’t work with what isn’t actually there.

And after all: Maybe the “truth” of the story isn’t the point.

What a story means can be more important — to those who recorded it, and to those who experience it years, decades, centuries later.

To me, what the story of the Green Children means is that the world is far larger and more unknowable than we sometimes think. It extends far beyond the borders we can see — and the lightbulb-over-the-head moment of realizing that’s the case is monumental.

There’s always something new to find.

You just have to be open to finding it.

Even if it’s something as seemingly impossible as green children.

Especially if that’s the case.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Bluesky @GhostMachine13.bsky.social, Twitter @GhostMachine13, and Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And for more games, don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via Rod Bacon, Helen Steed, Phil Catterall, AGGoH, Geographer, Paul Franks/Wikimedia Commons, available under CC BY-SA 2.0 and CC BY-SA 3.0 Creative Commons licenses; public domain (1, 2)/Wikimedia Commons]

Leave a Reply