Previously: Doveland, Wisconsin.

They called him the “Poe Toaster,” because, well… that was what he did: Annually, on the anniversary of Edgar Allan Poe’s birthday, he would quietly yet publicly toast the late author at the site of his original burial. But who was the Poe Toaster, exactly? Well… that, we still don’t know — much like the many other mysteries surrounding the life and death of Edgar Allan Poe. It’s unlikely we ever will learn the Toaster’s true identity, too; even so, though: The allure of the mystery endures and continues to fascinate after all this time.

Once a year, on January 19, he — at least, most people thought it was a “he”; it may not have been, but no one really knows for sure — would approach the former grave of Edgar Allan Poe in Baltimore, Maryland in the wee hours of morning, shrouded in black and carrying a silver-tipped walking cane. He brought with him a bottle of cognac — Martell, typically — and a glass, along with three red roses. He would pour himself a glass of cognac; then he would raise the glass to Poe, and drink. Finally, he would arrange the roses at the grave site, and situate the remainder of the bottle of cognac along with them.

All this completed, he would then depart, leaving behind the roses and the cognac, not to be seen again until the next year — and only by those awake early enough to witness him.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

The Toaster performed this somber ritual every year from at least 1949 — although possibly as early as sometime during the 1930s — until the 1990s, after which the tradition was seemingly carried on by a descendant, or possibly descendants, plural, of the original until 2009.

But even if it’s unlikely that we’ll ever learn precisely who the original Poe Toaster was, or who carried on the tradition for that last 10 years or so, the mystery is still worth considering. Let’s take a look, shall we?

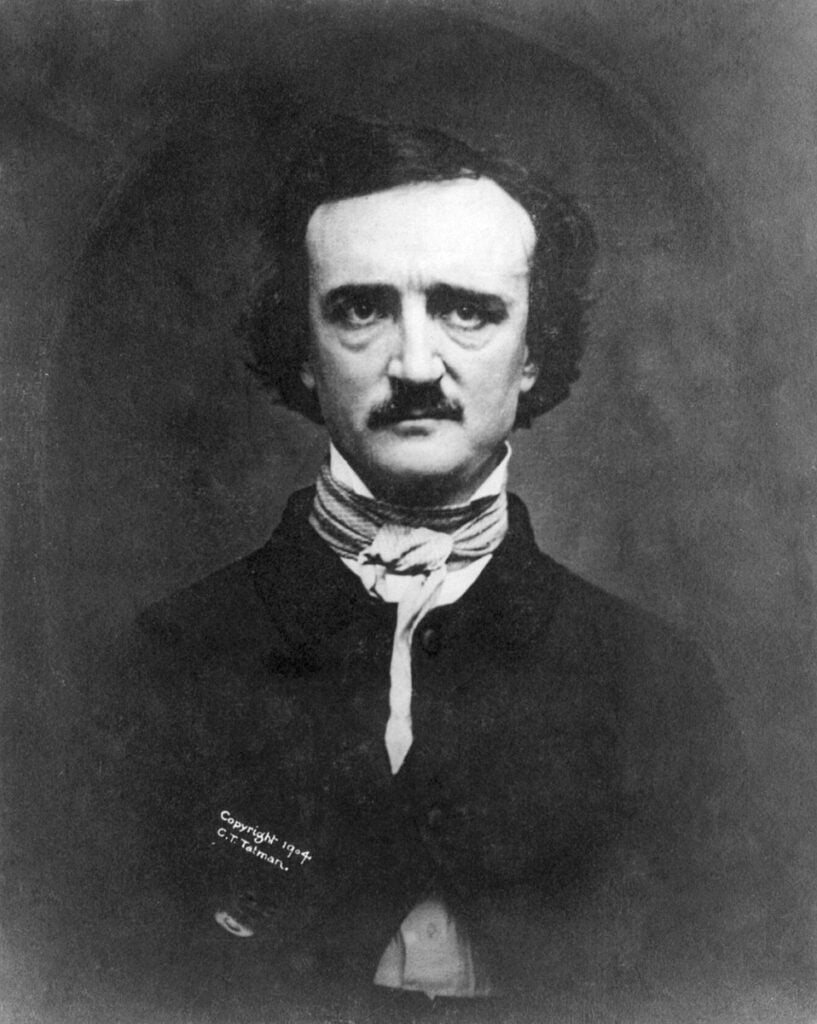

The Troubled Life Of Edgar Allan Poe

First, some literary history:

Poe’s biography has always been somewhat troublesome — as the Edgar Allan Poe Society puts it, “there is a great deal of information, but very few verifiable facts” when it comes to piecing together the timeline of the author’s life — but at this point in time, we’re fairly certain about the rough outline.

Edgar Poe was born on Jan. 19, 1809 — a Thursday, for the curious — in Boston, Mass., although just a few years later, following his father’s abandonment of the family and his mother’s untimely death from tuberculosis, he found himself in Richmond, Va. Fostered by merchant John Allan — from whence the “Allan” portion of “Edgar Allan Poe” originates — and his family, Poe moved around fairly frequently as a child; in 1815, the Allan family sailed to the UK, with Poe attending several schools in Scotland and London over the next five years. The Allans, with Poe in tow, returned to Richmond in 1820.

As a young man, Poe’s life continued to be tumultuous: He was perhaps engaged to be married, but also perhaps not; he attended the then-fledgling University of Virginia for a year, then dropped out; he fell out with the Allans, possibly over money, although possibly not; he moved around, from Richmond to Baltimore to Boston; and, eventually, with no other viable means to support himself, he joined the Army in 1827 at the age of 18. He had already begun writing by this time, as well, and that same year, he produced and anonymously published a poetry collection, Tamerlane and Other Poems. (If you’re familiar with the Christopher Marlowe play Tamburlaine, Poe’s poem is about the same guy.)

After leaving the Army in 1829, he made a brief stopover in Baltimore, staying with a handful family members who lived there — an aunt, a cousin, his older brother, and his grandmother — and publishing another book of poetry while he was at it. From there, he entered and subsequently dropped out of the West Point military academy, further fell out with the Allan family, spent some time in New York, and published a third collection of poems. In March of 1831, he returned to his family in Baltimore, just a few short months before his brother died.

In the years that followed, Poe continued publishing, now choosing to focus on prose rather than poetry; additionally, he gained then lost a job as an assistant editor of the Richmond-based Southern Literary Messenger in just a few short weeks. (He did later regain the position, however.) In 1836, he also got married, a union which was… problematic for more reasons than one. For one, his new wife was none other than the cousin from Baltimore, Virginia Clemm — a first cousin, at that; and for another, she was 13 years old, while he was 26. (Yes, yes, I know, times were different then, yadda yadda yadda — but it’s still… not great.)

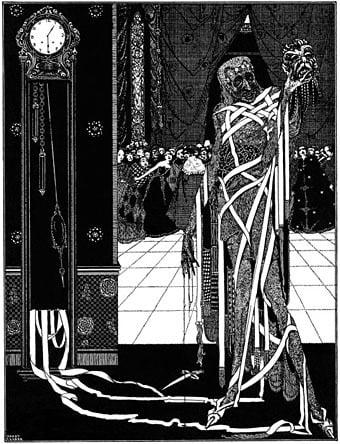

Over the next 13 years, Poe published the works for which he’s now best known: The novel The Narrative Of Arthur Gordon Pym was published in 1838; in 1839, he put out the two-volume short story collection Tales Of The Grotesque And Arabesque, which includes “The Fall Of The House Of Usher” (side note: Check out T. Kingfisher’s 2021 novel What Moves The Dead for a super fun riff on this story); and, while on staff at publications such as Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine, Graham’s Magazine, the Evening Mirror, and the Broadway Journal, wrote and published what we might refer to as his greatest hits — works like “The Murders In The Rue Morgue,” “The Pit And The Pendulum,” “The Tell-Tale Heart,” “The Masque Of The Red Death,” and, of course, “The Raven.”

Virginia died of tuberculosis in 1847 at just 24 years of age. Poe subsequently spent the next several years moving around again — New York, Richmond, Boston, Providence, and so on.

And then came the… oddness, and the author’s unusual and inexplicable death.

The Death Of The Author, And The Mysteries Therein

It began with a disappearance.

Poe vanished for a week between Sept. 27 and Oct. 3, 1849. He left Richmond on the former of those two dates, then reappeared in Baltimore on the latter, in what some might refer to as “a state.” Disheveled and delirious, he was taken to the Washington Medical College and attended to by physician John Joseph Moran. He died four days later, on Oct. 7, 1849, at the age of 40. His last words were reportedly, “Lord, help my poor soul.”

Moran was the only person to see Poe in his final days — the author was not allowed visitors — and his account of what transpired during those days changed frequently enough so as to render it unreliable at best. The cause of death has not been determined, although many theories — and conspiracy theories — exist. A death certificate has not been found.

And, crucially, the mystery of where precisely Poe was during his last, lost week has never been solved.

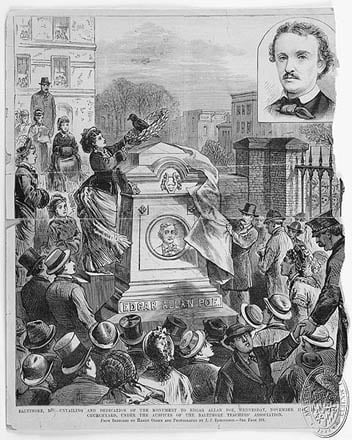

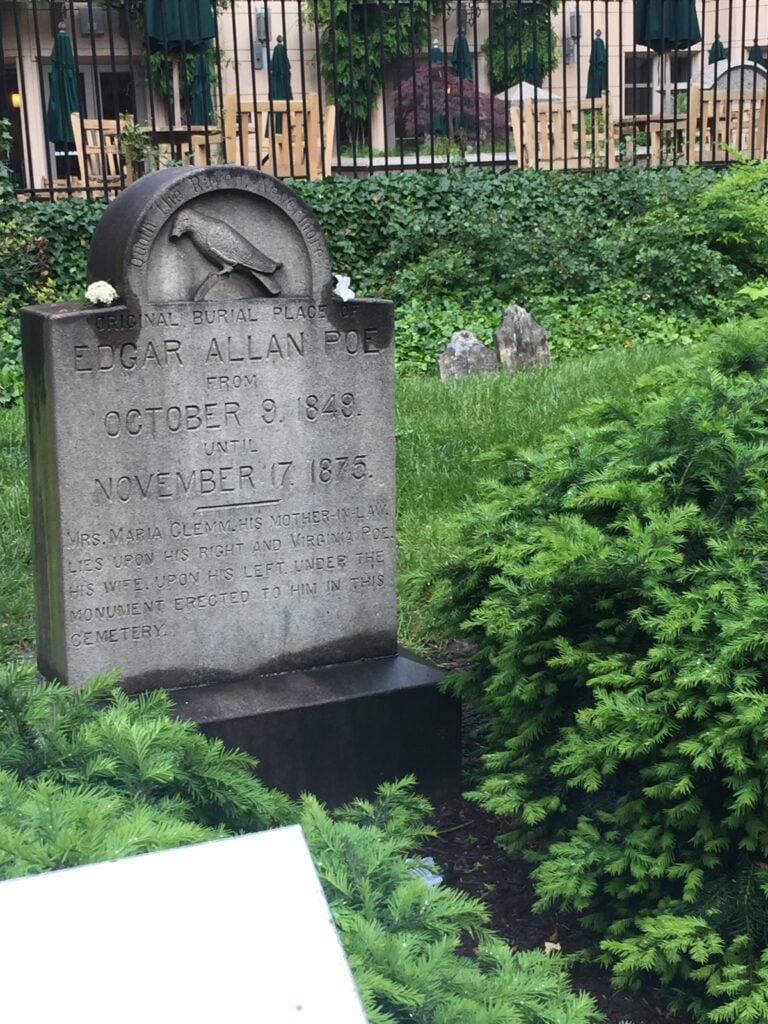

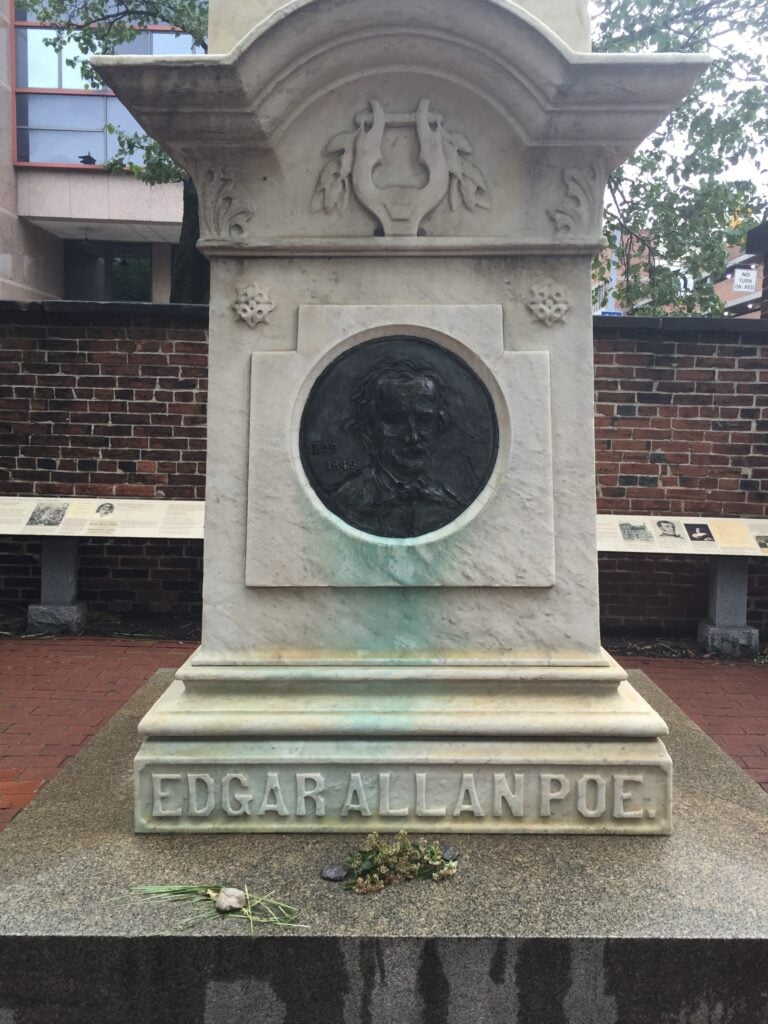

Poe was initially buried in an unmarked grave in the cemetery of Baltimore’s Westminster Presbyterian Church, now the Westminster Hall and Burial Ground. A sandstone marker bearing the number “80” was placed there some years later, with a marble headstone commissioned in 1860 to more formally mark the place; however, following a disaster at the railyard that resulted in the destruction of the marble stone, many more years went by without a proper marker. A local schoolteacher launched a campaign to raise funds for a full memorial in 1865, with the finished piece being installed in 1875.

Poe’s remains were exhumed and reburied at the site of the monument, with a cenotaph later being placed where his former gravesite was. The remains of both his wife, Virginia, and his aunt, Maria Clemm, were also later brought to the memorial and reinterred alongside Poe himself.

The memorial is open to the public, by the way; you can go see it pretty much whenever you want — it’s visible from the street. If you want to get up close and personal with it, or wander to the back of the burying ground to see Poe’s original resting place, the cemetery’s hours are 8am to 8pm daily. Guided tours of the cemetery are also available on the first Saturday of every month at 10am and 1pm. If you’re curious about the layout of the place, a map can be found here; Poe’s original grave is in the lower right corner, and the memorial in the upper left.

But the memorial is not where the Poe Toaster carried out his annual tradition. He did it at the original gravesite — the one at the back of the church, marked by a cenotaph.

And he did it for decades without ever being caught.

The Poe Toaster Raises A Glass

Precisely when the Toaster began appearing isn’t clear, but we do know that he had begun his curious ritual at least by 1949. We know this because of the first known reference to it that occurred in print, and when that reference was published: In the Sept. 22, 1950 edition of the Baltimore Evening Sun, an article by James H. Bready titled “Westminster Presbyterian Church Marks Two Milestones This Year” made note of “the anonymous citizen who creeps in annually to place an empty bottle (of excellent label) against the tomb of Poe, on the anniversary of his death.” Logic states that, if the tradition had already been observed more than once by the fall of 1950, then it had occurred at least twice before, making its latest possible start date Jan. 19, 1949.

(Per the Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore, Bready later said that his reference to Poe’s death date, rather than his birthday, was probably an error on his part. Mistakes happen.)

However, it’s been suggested that the Toaster could have begun his annual toast sometime in the 1930s. Members of the Westminster Presbyterian Church reportedly stated in the 1970s that they recalled it occurring then; however, as Trevor J. Blank and David J. Puglia noted in the 2014 book Maryland Legends: Folklore From The Old Line State, “supporting evidence is lacking.”

If the Toaster had made his first appearance in 1949, the year was a significant one: It marked the 100th anniversary of Poe’s strange death. But as the record is lacking, alas, there’s no way to know for sure.

Regardless, the Toaster — the original one, at least — was a creature of habit. He made his appearance every year, always on the same date, and always within the same window of time—typically between midnight and 6am, reported Laura Lippman (yes, that Laura Lippman) for the Baltimore Sun in 2000. He always brought the same cognac; he always performed the same gesture; and he always laid the three roses he carried with him in a particular pattern.

The significance of both the cognac and the roses has never been fully determined; the accepted explanation is that the cognac was simply the Toaster’s drink of choice (cognac does not factor prominently into any of Poe’s stories — not like some other tipples I could mention), while the roses are believed to represent the familial trio buried at the grave site together: Poe, his wife Virginia, and his aunt and Virginia’s mother, Maria Clemm.

What we know of the Toaster’s regular routine is largely thanks to Jeff Jerome, who was the curator of the Edgar Allan Poe House and Museum in Baltimore for several decades. Jerome has recounted his “origin story” as an observer of the Poe Toaster many times over the years, although what I’ve found to be the most complete version was published over at Baltimore radio station WBAL’s website in 2013.

The way he tells it there, Jerome — prior to his time at the Poe House — became a tour guide for Westminster Hall and Burying Ground itself in 1976, at which time he found the clipping from the 1950 Baltimore Evening Sun article making note of the Toaster. After hearing other church members and the caretaker corroborate the story, he made sure to pay attention the next time the Toaster was due to come around — and sure enough, on the morning of Jan. 19, 1977, Jerome found the half-finished bottle of cognac and the three roses placed at the foot of the original grave at the back of the church.

Each year thereafter, Jerome stayed on the lookout; he eventually caught his first glimpse of the Toaster himself a few years later, camping out in the church catacombs overnight to do so. From Jerome, we get the description of the Toaster’s attire — well-dressed, all in black, with a wide-brimmed hat and a white scarf, walking stick in hand — and the details of precisely what the Toaster does at the grave.

But over time, others contributed as well; watching for the Poe Toaster also became a tradition in and of itself, especially after 1990, when Life Magazine published a photograph purported to be of the Poe Toaster in action. (The photo can be seen here, although note that it’s grainy and very low resolution. Note, too, that the original site that hosted it, HouseOfUsher.net is now offline; however, Peter Forrest, who ran the site for many years, is currently in the process of moving some of the more popular contents of HouseOfUsher.net to his own website for posterity.)

The vigil grew, year after year, as the Toaster continued his routine — until one year, he informed us that things were going to change, and soon.

He was, after all, only human; he would not live forever.

And what then? What, after he had shuffled off this mortal coil and left this world?

The Poe Toaster: The Next Generation

The Poe Toaster had planned for this eventuality. (Of course he had; how could he not?) He even informed Jeff Jerome, and the public at large: After the 1993 visit, he left a note at the grave stating that “the torch will be passed.”

The implication, those who watched were to understand, was that the Poe Toaster, then getting on in years, would soon be retiring; he had, after all, been toasting Poe for at least 44 years, and was undoubtedly not a young man when he began the tradition in the first place. But after his time had passed, the note suggested, someone else would take over, although who they were or how they would be chosen was not specified.

In 1999, another note was left, this time confirming that the original Toaster had died in 1998. The note stated that the tradition had been passed on to “a son,” however; indeed, it was this “son” who had performed the 1999 toast.

Over the next decade, the new Toaster continued the tradition, although it became clear through several other notes left during that time that he — or perhaps “they”; some believe that multiple people switched off on Toaster duties from year to year — did so reluctantly. He frequently forewent the distinctive style of dress his predecessor had made famous, showing up in street clothes instead, reported the Herald-Citizen (via Smithsonian) sometime after the changeover occurred. He also periodically left notes that, for the first time in the history of the Toaster ritual, commented on current events.

In 2001, for instance, about a week and a half before Super Bowl XXXV, which saw the Baltimore Ravens face off against the New York Giants, the letter predicted a win for the Giants while cursing the Ravens in the same breath:

“The New York Giants. Darkness and decay and the big blue hold dominion over all. The Baltimore Ravens. A thousand injuries they will suffer. Edgar Allan Poe evermore.”

Notably, the prediction for the Giants riffed on the final line of “The Masque Of The Red Death”: “And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.” The prediction turned out to be incorrect, however, with the Ravens winning 34-7.

Then, in 2004, the Toaster seemed to take issue with France, whose political leaders had expressed criticism of the U.S. involvement and aggression in the Iraq War. Read the note that year:

“The sacred memory of Poe and his final resting place is no place for French cognac. With great reluctance but for respect for family tradition the cognac is placed. The memory of Poe shall live evermore!”

According to Jeff Jerome, a final letter was left sometime between 2005 and 2008, as well, although its contents upset him so much that he decided not to make them public. What precisely this note said remains unknown to the world at large, although Jerome did state to WBAL in 2013 that it seemed to announce the impending end of the Poe Toaster tradition.

And, indeed, the 2009 toast, which coincided with Poe’s 200th birthday, turned out to be the final toast. The Toaster failed to appear in each of the three years following, prompting Jerome to declare in 2012 that the tradition had officially ended.

The Poe Pretender

At this point, it’s worth talking about the many theories about the Poe Toaster’s identity. But although we can’t really talk about who the Poe Toaster was, since, y’know, we still don’t know, we can talk about who the Poe Toaster was (probably) not.

The Toaster was (probably) not Jeff Jerome. Although some have theorized that it was him all along, he is adamant that it was not; nor does he know the true identity of the Poe Toaster. True, we more or less just have to take him at his word — but I’m content to do so. For one thing, he’s not old enough to have been the original Toaster; also, I’m fairly certain that others holding vigil over the years would have observed the Toaster and Jerome existing simultaneously in the same place, putting the kibosh on any “WELL, HAVE YOU EVER SEEN THEM IN THE SAME ROOM?” theories that might be floating around out there.

He’s also (probably) not Sam Porpora. Porpora, then 92 years old, came forward in 2007, claiming to have been the Toaster. He told the Baltimore Sun that he had invented the tradition in the 1960s in order to raise funds for the Westminster Presbyterian Church. “It was a great promotion,” Porpora said in a piece published on Aug. 15 of that year. “I restored Poe to greatness.”

Porpora did rescue the church from falling into decay through his efforts to raise awareness and begin tours of the catacombs; he was also a longtime friend and mentor of Jeff Jerome. “He deserves a medal for what he did for that place,” Jerome told the Washington Post in 2007. “He kept it in the public eye when no one else was paying much attention to it.” Indeed, it was under Porpora’s watch that Jerome first became a tour guide for the church, and it was Porpora who ignited the passion for Poe that would eventually lead Jerome to his position at the Poe House.

But Jerome was also quick to point out the many inconsistencies in Porpora’s story — not the least of which is that there’s an actual record of the tradition existing long before Porpora’s claim of starting it in the late ‘60s. Said Jerome to WaPo, “It’s not Sam. He’s like a mentor to me and I love him, but, believe me, it’s not him.”

The Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore further refuted Porpora’s claim. Reported the Associated Press in 2007, “Members of the Poe Society insist they recall members of the old congregation — all now dead — talking about the Poe Toaster before Porpora says he made it up.” The Society also states on their website that they, like Jeff Jerome, have no insider knowledge about the Toaster and are not privy to his true identity.

And lastly, there are the “Faux Toasters” — those who, in the spirit of the original, took it upon themselves in the years following the final toast to leave cognac and roses at Poe’s grave. They, too, are were none of them the original Poe Toaster or the Toaster’s chosen heirs — and yet, as Michael Madden wrote for the Baltimore Sun in 2011, who or what is the Poe Toaster, really, but a concept or an idea — something bigger than any single person.

It didn’t matter that the Faux Toasters weren’t the original Toaster, or even chosen by the Toaster himself to carry on the tradition. “What mattered,” wrote Madden, “was that, on that cold, rainy night, [they] delivered the passion, the respect, and the tribute that our beloved poet richly deserves.” Concluded Madden, “The Poe Toaster failed to appear? I was there. The Poe Toaster came.”

The Legacy Continues

Indeed, it was in that spirit that, in 2015, the Maryland Historical Society decided to revive the tradition: They held a competition of sorts in the waning months of that year to choose a new Poe Toaster, who would carry the annual ritual into the next year and help it evolve into something new.

As Katie Caljean of the Maryland Historical Society told CBS News in October of 2015, “We’re not looking for somebody to replace the Toaster or try to do exactly what the Toaster used to do; we’re looking for a new spin on the tradition to celebrate and honor the past and our dear friend, Edgar.”

Elaborated Jeff Jerome, “[The new Toaster] will not be coming here in the middle of the night and climbing over the fence. This will be a public event for Baltimore to celebrate, and any time Edgar Allan Poe is celebrated is good with me.”

Those who wished to throw their (wide-brimmed) hats into the ring were encouraged to submit applications to audition; around a dozen finalists were then select to perform on Nov. 7, 2015 at the Historical Society’s headquarters. “Celebrity judges” were present, but, as Caljean said to CBS News, the real judges were the audience — the people of Baltimore — who selected the winner. Votes were taken via secret ballot.

Then, on Saturday, Jan. 16, 2016 — three days before Poe’s actual birthday, which fell on an inconvenient weekday that year — the celebration commenced and the new era dawned.

First, reported the Baltimore Sun, there was a dramatic reading of “The Cask Of Amontillado” (one of my personal favorites!), followed by an apple cider salute to Poe and a raffle for a themed cake. Then, bystanders and participants gathered outside by the Poe monument at the front of the cemetery — rather than the original grave at the back — and watched as a bearded man, dressed in the traditional black and sporting the trademark Toaster’s hat and scarf, arrived.

He carried with him the appropriate accoutrements — the cognac and the roses — but also something new: A violin. He played “Danse Macabre” as he approached; then, after setting the violin and bow on the monument, he spoke a few words in Latin: Cineri gloria sera venit — an epigram from the Roman poet Martiall that translates to, “Fame comes too late to the dead.”

He drank the cognac.

He arranged the roses.

And then, with a nod, he was gone.

The new Toaster returned in 2017, although I’ve been unable to determine if he’s made any appearances since then.

UPDATE, Jan. 10: Jeff Jerome reached out to TGIMM on Facebook with some additional information about what the Poe Toaster has been up to over the past few years — and now! The Poe Toaster actually did make several appearances during the pandemic, even when no one was present to witness him, in order to “illustrate his commitment to the tribute,” Jerome says. And, even better, there will be festivities for 2023! Information about the planned event this year can be found at the Facebook page Edgar Allan Poe: Evermore.

PREVIOUSLY: Regardless, though, it seems the Toaster is always there, even if he’s not there.

Maybe the mystery has been solved after all:

For we are, all of us, the Poe Toaster.

[Photos via Wikimedia Commons (1, 2, 3, 4, 5), available via public domain and CC BY 3.0 Creative Commons license; Lucia Peters (2)/The Ghost In My Machine.]

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And for more games, don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!