Click here for content warnings.

It’s 2011. You’re browsing Reddit. You see a link posted there — a web comic, hosted at a site called Naver. It’s drawn in the style you associate with anime, although the text is in Korean, not Japanese. Depending on whether you speak Korean, you may or may not be able to read the comic’s title — “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost” — and you may or may not know that, in its official parlance, it’s not called a comic, but a webtoon.

Regardless, As you scroll down — because that’s the way this comic is read; it scrolls vertically, rather than having you click through the panels horizontally — you follow the story of a young woman walking home alone in a city at night. You realize the story might be a horror story as you see the young woman catch sight of someone behaving… oddly further down the sidewalk. Your hackles rise just a bit, and your teeth set slightly; you’re on edge — and yet, you continue scrolling.

Again, you might not know it at the time, depending on your knowledge of Korean as a language or of Korean web culture, but “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost” is drawn and written by a Korean webtoon creator who publishes under the name Horang — and although this particular webtoon is far from the only webtoon Horang has published, it’s about to go down in history as one of the most memorable webtoons ever to hit the internet.

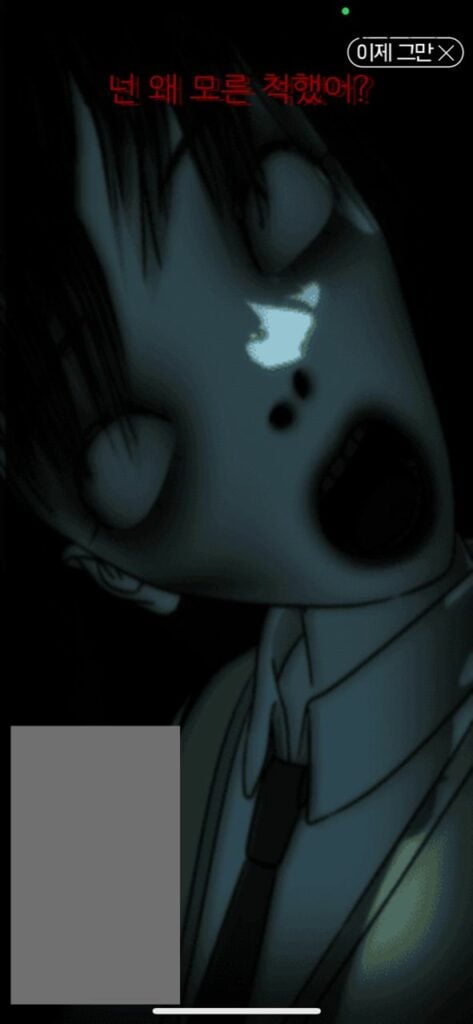

What you’re not expecting, you see, is for the comic to come alive as you read it — but that’s exactly what it does: You scroll, and you scroll, and you scroll… and suddenly, the strange figure’s head spins 180 degrees, Exorcist-style, while a creaking, clacking, bone-chilling sound emerges from your device’s speakers.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

You jump. You might, depending on whether you’re the type to scream when startled, make an involuntary noise. Your heart pounds. You’ve just been jumpscared — but the fact that you were jumpscared by a comic, which doesn’t typically move or make sounds, strikes you as enormously clever.

You love it.

You can’t wait to send this thing to everyone you know.

You can’t wait to see it catch them by surprise, too.

***

Does this scene feel familiar to you? If it does — and if you’re anything like me — odds are you still remember when you first encountered “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost” all those years ago, and haven’t stopped thinking about its nifty, terrifying tricks even after all this time.

But although “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost” is certainly the most well-known horror webtoon Horang has produced, I have good news for anyone who loved it back then, but hasn’t kept up with the webtoons scene since for whatever reason: There’s more where it came from. Much more — and these days, nearly all of it is widely accessible in both Korean and English.

Welcome to the horror webtoon world of Horang.

Come on in.

There are plenty of chills waiting for you… if you dare.

Meet The Tiger Writer: Horang And His Early Work

Horang, which translates to English as “Tiger,” is a pseudonym as well as a mononym, of course; it’s the name under which artist and writer Choi Jong-ho creates and publishes his work. Born in 1986 and educated at Gyeonggi Commercial High School and Sungkonghoe University in Seoul, Horang began publishing comics online in 2007, first at Korean web portal Daum before making the move to Naver a few years later. The pseudonym, he has said, comes from the fact that he was born in 1986 — the Year of the Tiger, according to the Chinese zodiac — along with the presence of the character 虎 in his given name.

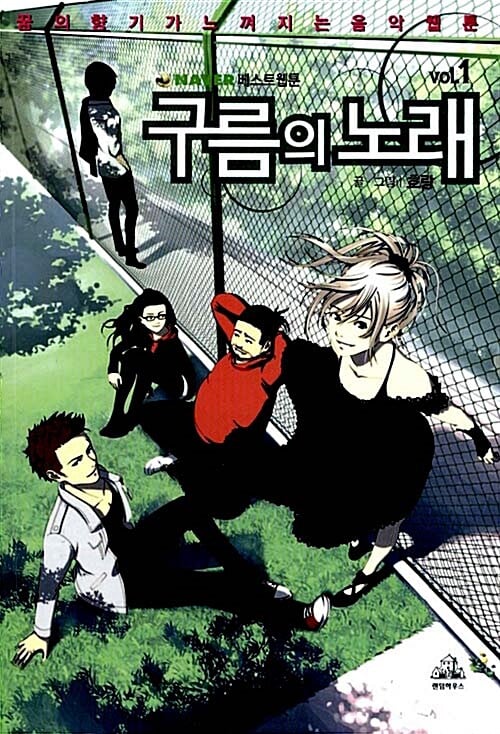

Horang’s earliest works, “천년동화” — a title Google Translate renders as “A Thousand Years Fairy Tale” or “A Millennium Fairy Tale” — and “구름의 노래,” or “Song Of The Clouds,” both saw their initial publication over at Daum. Unlike the works for which Horang would later become known, these two pieces were not horror stories; my understanding is that the first was a collection of retellings of traditional fairy tales and folktales, while the second was a coming-of-age story centered around a band of teenage musicians. Both were later serialized on Naver, as well as traditionally published as physical volumes by Random House Korea.

2011, however, was something of a turning point. That year, Horang contributed two comics to Naver’s annual summer horror webtoon collection, titled 2011 Mystery Shorts — and shot more or less to instant fame, thanks to the innovative techniques he used to tell his set of extremely effective ghost stories.

And the internet has never been the same since.

A Haunting Beginning: “Oksu Station Ghost,” “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost,” And The 2011 Mystery Shorts

Published over the course of about two months, between the middle of July and the middle of September, 2011 Mystery Shorts comprised around 30 horror stories from a wide variety of writers and artists working within the webtoons space. Horang’s contributions — “옥수역 귀신,” or “Oksu Station Ghost,” and “봉천동귀신,” or “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost” — made up episodes five and 20 respectively.

“Oksu Station Ghost” was among the earliest arrivals, hitting the internet on July 21 and taking off in Korea immediately, thanks to its innovative and effective technical tricks.

The webtoon tells the story of a young man waiting for a train at Oksu Station, located on Line 3 and the Geyongui-Jungag Line of Seoul’s subway system. While waiting on the platform, the young man spots a woman behaving strangely, wandering to-and-fro across the platform and staggering about. Believing her to be drunk, he begins posting about what he’s witnessing in a thread on an online message board system or web forum — only to look up from his phone and find that she’s seemingly vanished. Concerned, he wonders if she’s fallen onto the tracks.

One participant in the message board thread urges him not to examine the tracks; according to this participant, there’s something weird in the background of the photograph of the woman the young man had previously posted — something potentially… unearthly. But the young man approaches the tracks anyway — at which point a huge, bloody, disembodied hand springs out of the tracks and drags him down, right into the path of an oncoming train.

The story finishes with a postscript: “The next day, there were several headlines about a man and a woman that died by suicide at Oksu Station,” the first of the final two panels reads. “People assumed they had been lovers,” the second panel begins, before concluding with this last statement: “But the police found no connection between the two.”

Unlike standard web comics that read from side to side, often requiring readers to click through from panel to panel, webtoons are designed with smartphone browsing in mind: They scroll vertically, without the need to click or tap through to view each panel. Horang makes great use of this characteristic, hiding some clever Javascript triggers within his stories. That’s what animates the ghost’s spinning head in “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost” — and in “Oksu Station Ghost,” it’s what causes the ghost hand to seemingly spring out of the panel directly us, animated and active, as an eerie, chilling sound suddenly blares out of the speakers of whatever device you’re using to view the webtoon.

It’s a jumpscare, yes — but although jumpscares are often maligned, a good one can be used to great effect. That’s exactly what’s happening here: The sound and motion break our expectations about comic strips — that is, that they’re silent and composed entirely of static panels — which, in turn, offers an unexpected and incredibly successful moment of fright.

It was this jumpscare — and the cleverness of its execution — that entranced readers upon the webtoon’s initial publication; subsequently, it spread rapidly among Korean audiences, offering the perfect chill to temper the hot summer weather.

Then came Horang’s second contribution to the 2011 Mystery Shorts collection — the one that would launch the webtoon creator to international fame. “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost,” about a young woman who encounters the spirit of a woman looking (horrifyingly) for her lost child in the Bongcheon-dong area of Seoul, was first published in its original Korean on Aug. 23, 2011 — and this time, it spread globally, appearing on Reddit, YouTube, the blog of influential American cartoonist and comics theorist Scott McCloud, and more. Utilizing the same tricks as “Oksu Station Ghost,” it surprised readers at two key moments with unexpected movement and startling, spine-tingling sounds — and for Western readers in particular, where the webtoon format itself was a novelty? That was something many of us had never seen before. And boy, did it make an impression.

Fan-made English translations of “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost” followed quickly on the heels of the webtoon’s original publication; official English translations of both it and “Oksu Station Ghost” were also produced not too long after that, appearing in September as additions to the original 2011 Mystery Shorts collection. Both of them — but especially “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost” — remain popular, spoken of in almost mythical terms as Redditors and other Extremely Online folks reminisce about what it was like to encounter it for the very first time, not having any idea what was in store for you as you scrolled.

But there is far, far more to Horang’s work than just these two webtoon. For the curious, here’s the full list of all of Horang’s horror webtoons — or at least, all of the ones for which I’ve been able to locate links — that have been released at the time of this writing:

- In 2013, “Ghost In Masung Tunnel,” set in a haunted motorway tunnel also known as Maseong Tunnel, appeared in the Legendary Home collection in both Korean and English.

- In 2015, “Wall-Knock Ghost,” also known as “Knock Knock,” appeared first in the Creepy collection — which I’ve also seen referred to as the Goosebumps collection — in Korean, then in the collection’s English language translation, Chiller. (I previously covered the urban legend game seen in the story in our Most Dangerous Games feature.)

- In 2016 and 2018, two stories arrived as exclusives to the Webtoons KR app (and are, therefore, available only in Korean), in collections titled Phone and Do Not Play.

- In 2020, Horang released a full collection of his own work in both Korean and English, featuring six new stories — “The Ghost In The School Stairwell,” “The Ghost In The Fridge,” “Street View Ghost,” “The Ghost In The Elevator,” “The Ghost Of Turtle Playground,” and “Ghost on the Highway” — plus remastered versions of both “Oksu Station Ghost” and “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost.” In English, the collection was called simply Horang’s Nightmare.

- And then in 2022, the No Scroll collection — translated as Scroll If You Dare in English — included “Busan Karaoke Ghost,” set in a seemingly haunted karaoke joint in Busan.

With each new story, Horang’s particular world of horror grew, underlining as it did how resonant it is for modern, digital-age audiences. Typically written from the first-person perspective, they have a classic creepypasta-type feel to them, with the kind of immediacy of storytelling we’ve come to expect from these kinds of tales — but Horang’s stories? They’re more than just immediate.

They feel like they could happen to us.

Despite — or, perhaps, because of — the fact that they’re relayed using a heightened form of storytelling (e.g. webtoons), they feel like they could be real.

Beyond Jumpscares: The Uncanniness Of Horang’s Horror

It’s tempting to refer to Horang as Korea’s answer to Junji Ito, Japan’s infamous horror mangaka — but although both artists work within comics as a medium and horror as a genre, their stories speak to very different things. Horang’s tales, I would argue, are smaller and quieter, more intimate and less cosmically vast than Ito’s; whereas Ito’s work presents the universe as a whole as fundamentally unknowable — something beyond human comprehension in its strangeness — Horang focuses more on the horror in the everyday, in the familiar made strange. To put it in Western terms: If Junji Ito is cosmic horror, Horang is the uncanny.

Make no mistake, though: By “smaller,” I don’t mean “lesser.” Horang’s stories are positively chilling, even without taking into account the webtoon tricks that bring them to literal life. By “smaller,” I mean that all of these stories begin with something we know — something commonplace, something we’re likely to encounter in our own lives, often on a mundane or day-to-day basis: A train commute, as in “Oksu Station Ghost”; a walk home at night, as in “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost”; an off-limits staircase, as in “The Ghost In The School Stairwell,” which appeared in the 2020 collection Horang’s Nightmare; moving into a new apartment alone, and a refrigerator that just won’t stay shut, as in “The Ghost In The Fridge,” also in Horang’s Nightmare; getting stuck in an elevator, as in “The Ghost In The Elevator,” another Horang’s Nightmare tale; even just browsing Google Street View, as in “The Street View Ghost,” again in Horang’s Nightmare.

Then, crucially, the stories ask: What if? What if there’s something more going on with that person’s behavior than just public intoxication? What if that person on the sidewalk isn’t just coincidentally walking home at the same time we are? What if that staircase is off-limits for a reason? What if there’s something wrong with the fridge that isn’t a mere mechanical issue? What if the elevator isn’t just suffering a standard malfunction? What if that glitch in Street View is more than just a glitch?

We’ve all been there, the stories say — but what if, when we were there, something had happened that just… nudged the needle a little? Something that tipped the event over from odd but understandable to dangerous and potentially ghostly?

These events, the stories say, could very well have happened to us — if things had gone just a tiny bit differently.

In some cases, the stories actually did happen to real people, at least in part: Several of Horang’s tales are loosely based on tragic true events. In the case of “Oksu Station Ghost,” for instance, the events in question occurred in 2009; on Feb. 14 that year, at approximately 5:30am, a man died by suicide on the tracks at Oksu Station — and then, just a few hours later, a hospital worker who had gone to collect the body also died after being struck by a train.

Less is known about the inspiration for “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost,” but according to Aju News, Horang has reportedly said that the webtoon is “a fiction based on a suicide case that took place in an apartment complex in Bongcheon-dong, Seoul in 2007.”

And then there’s “The Ghost In Masung Tunnel,” which is set within a motorway tunnel in Yongin known for its treacherous nature: Per Zum News, the tunnel, a particularly narrow one originally opened in 1994, has been the site of “so many traffic accidents” each year that it ranks among the top 10 locations for such collisions.

Of course, there are no reports of actual ghosts or hauntings in any of these locations — but, again, the point is the grounding in reality, and the asking of the what-if. Together, these two qualities drive the stories home for us, hitting us right where it counts: It could happen. It did happen. What might happen now?

With each story, Horang has further developed his craft. The animations are present in most of them; later stories, however, also incorporate photorealistic imagery, sometimes placing illustrated characters within backgrounds or environments that look more like photographs than illustrations themselves. This is especially true for the webtoons in Horang’s Nightmare, where this technique can be seen in stories like “The Street View Ghost” and “The Ghost Of Turtle Playground.”

Additionally, the app-only stories make great use of the fact that they can specifically only be read on smartphones; the one in the 2016 collection Phone, for instance, features AR capabilities that make it seem as if you’re FaceTiming with a ghost. (Think Yotteno, but for real.)

These techniques all add to the feeling that the events told in the webtoons could happen to us — that they could be real, if only, if only, if only.

But the most recent Horang horror webtoon is, to me, the most exciting of the bunch. Titled “Busan Karaoke Ghost” and published in 2022 in the Scroll If You Dare collection, it has all the hallmarks of a classic Horang tale — but it’s also a little bit… different. And from where I’m sitting, those differences tell us a little bit about what we might be able to expect from Horang’s horror webtoons going forward. TL;DR? The direction he’s moving in is quite an exciting one, indeed.

Horang’s stories frequently have some kind of reveal or reversal at the end that changes how we view everything that happened prior: In “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost,” we learn about the apartment building’s history, which reveals to us the identity of the ghost; in “Knock-Knock,” we learn who the culprit of the murder is; in “Street View Ghost,” we discover that an alibi previously believed to be airtight is, in fact, yet more deception; and so on.

With “Busan Karaoke Ghost,” however, the nature of the reversal is something we haven’t seen before. Up until the very end, what we seem to have read is a story about a young man who visits an old friend — a young woman — only to have a horrifying experience at the karaoke parlor her family owns. Whereas in an earlier Horang story, we might have expected to find something out about the karaoke parlor itself, or the land on which it had been built, or even about the friend or her family.

Instead, though, we learn that our narrator is not a trustworthy one — that the young man’s perception of the events we just witnessed through his eyes doesn’t reflect reality: His family has been dead for some time, lost in a house fire years ago. He’s spun the situation inside his own head in order to tell himself a different story. He hasn’t yet come to terms with the loss of his own family, and his mind is trying desperately to protect him from the trauma of that realization.

Viewed another way: It’s not the karaoke place that’s haunted.

It’s our narrator.

This difference in the nature of the reversal here is subtle — but despite its subtlety, it’s still quite a major one. Because of it, the narrative reaches an additional level of complexity to which the earlier webtoons don’t quite get. This, I think, bodes well for future Horang stories; it’s development not just in the technology used to tell the stories, but in the depth and complexity of the stories themselves. It’s evidence of Horang’s maturation as both an artist and a writer — that is, as a complete and whole storyteller. And I, for one, am looking forward very much to seeing where he goes from here.

What Lies Beyond: Modern Nightmares & Looking To The Future

And time, indeed, marches on: The original versions of “Oksu Station Ghost” and “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost” no longer “work” in the way they did upon their initial publication. Both required Adobe Flash to run, and with the discontinuation of support for Flash at the end of 2020, they now function (ironically) as purely static comics.

But that doesn’t mean you can’t still experience them in all their glory. When webtoons with the kinds of motion and sound effects that Horang utilized early on began to pick up steam, Naver developed a set of tools intended to make it easier for artists to incorporate these kinds of effects into their works; they launched in 2015 as the Webtoon Editor. As Horang continued to publish, he has continued also to make great use of the tools available, perhaps most notably in the 2020 Horang’s Nightmare collection. In addition to its hitherto unseen stories, this collection also included remastered versions of both “Oksu Station Ghost” and “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost” which definitely, definitely still work now.

It’s worth noting that both of these remasters, along with all of the other webtoons Horang has created using the updated technologies, are automatically muted when you first load them — that is, readers must actively turn on the sound effects to experience the jumpscares in their fullest forms. (The motion still plays whether or not the sound is on, so even if the webtoon is kept muted while being viewed, the visuals will still move at key points regardless. Just, y’know, heads up about that, if you’re startled by unexpected movement.)

While some might argue that this takes away from the surprise of the whole thing, I think it’s both a smart and necessary decision on Horang’s and Naver’s part; it lets people choose to opt in, rather than opting them in without their consent. Being scared because you want to be scared is fun. Being scared because someone has sprung it on you without your consent is not — and, in fact, can be deeply traumatic. Consent matters, always.

It’s been some time since Horang has published a new webtoon; as of late 2022, his Studio Horang blog indicated that he has been working on other projects, including the development of a webtoons image slicing tool and an adorable mobile game that sees you trying to stop a whole bunch of incredibly cute cartoon mice from stealing a cake. “Oksu Station Ghost” also received a feature film adaptation, which was released in April of 2023.

We can only hope that there’s more to come — but in the meantime, we’ll always have “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost,” right?

For further reading, here’s where you can find all of Horang’s published horror webtoons:

- Mystery Shorts (2011): Original Korean and English versions of “Oksu Station Ghost” and “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost.”

- Legendary Home (2013): Korean and English versions of “The Ghost In Masung Tunnel.”

- Creepy/Goosebumps (2015): Original Korean version of “The Wall-Knock Ghost.”

- Chiller (2015): English version of “The Wall-Knock Ghost,” translated as “Knock Knock,” plus a republication of “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost.”

- Phone (2016): WebtoonsKR app exclusive collection.

- Do Not Play (2018): WebtoonsKR app exclusive collection.

- Horang’s Nightmare (2020): Six new stories, plus remastered versions of “Oksu Station Ghost” an “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost.” Available in Korean and English.

- Do Not Scroll (2022): Original Korean version of “Busan Karaoke Ghost.”

- Scroll If You Dare (2022): English translation of “Busan Karaoke Ghost.”

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And for more games, don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via LERK/Wikimedia Commons, available under a CC BY-SA 4.0 Creative Commons license; Fred Ojardias/Flicker, available under a CC BY 2.0 Creative Commons license; StockSnap, 652234/Pixabay; screenshot/WebtoonsKR, taken by yours truly.]

*Content warnings: Suicide, homicide.

Thank you for posting this. I have always wondered about the history of this Korean comic.

So i was looking around on here to see if one of my favorite creepypastas was on here and it wasn’t so I recommend you check out Cold War relics there’s about 4 of them i think

Thanks for the suggestion – we’ll take a look!