Previously: Haunted Phone Numbers With Scary Stories.

In 2020, if you spent enough time in the right corners of Facebook, you might have come across a profile with a curious avatar — one that looked like a cartoon girl with a white face and long red hair. Her eyes, though… if you looked closely, you’d see her eyes — or rather, her lack of them. In their place were what looked like black pits. Her name, according to her Facebook profile, was Yotteno.

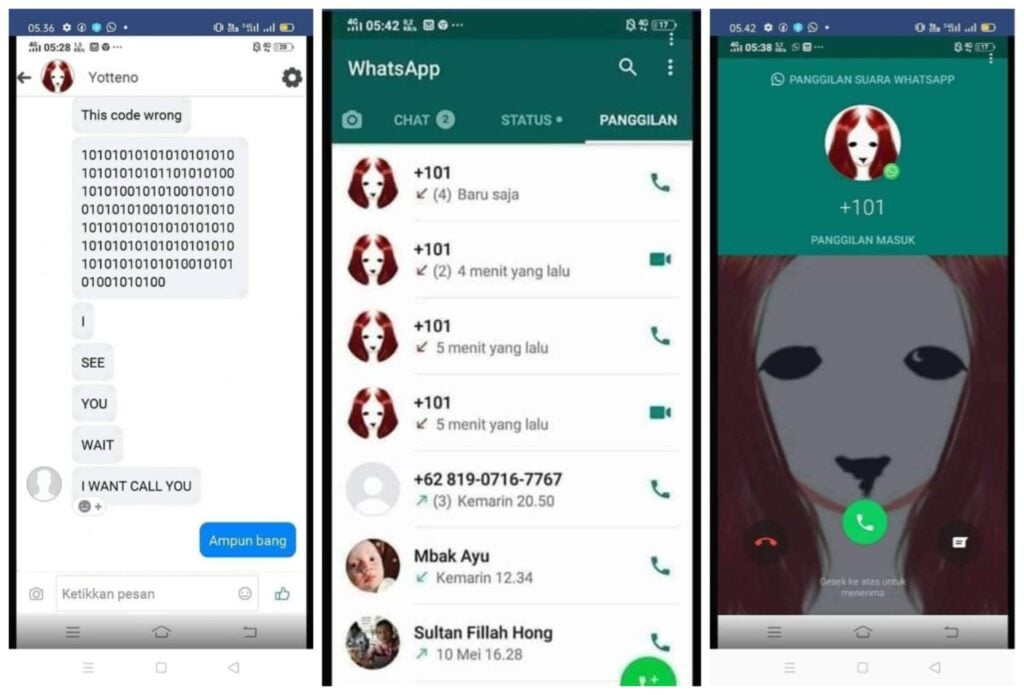

Maybe you were curious. Maybe, amid the sea of illustrated profile pictures, something about this illustrated profile picture piqued your interest. So, you messaged her — and what followed was a conversation that confused you. She sent you a code. You couldn’t solve it. And when you failed, she wrote to you, “I SEE YOU.” She wrote, “YOU DIED TODAY.” She wrote, “I WANT TO CALL YOU.”

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

And then, a notification from your phone: You had a video call coming in on WhatsApp — from Yotteno.

You hadn’t given her your number.

Did you pick up the phone?

Or did you just let it ring until she gave up?

I hope you let it ring — because when Yotteno wants to call you…

…Well, answering it might be the last thing you ever do.

***

Or at least, that’s what the stories would have you believe — assuming, that is, you’ve even heard of them. Tales of Yotteno, her allegedly haunted Facebook profile, and her mysterious WhatsApp calls swept the internet in 2020, but only in Indonesia. For roughly a week in May of that year, Yotteno was all the Indonesian branch of the community of Extremely Online folks could talk about — but, somewhat remarkably, the legend stayed local. It didn’t travel outside of the country, so it’s only by chance that I, as a non-Indonesian person, even found out about it.

It’s a fascinating one, though — a legend that’s all smoke and mirrors, seeming to be more substantial at first than it ultimately is, but worth exploring all the same. Yotteno fits within the pantheon of technology-based urban legends, internet-based urban legends, and phone-based urban legends, all in one go, echoing some common themes and reminding us again of our preoccupations with them.

So: Let’s explore, shall we?

Before we start, I do need to preface this one by acknowledging the limitations of both myself as a researcher and the nature of the research itself. Since Yotteno never made it out of Indonesia, that means that (of course) the only the only sources discussing the legend are in Indonesian, a language I don’t speak. Thanks to the wonders of the internet, I’m able to access some of these sources via Google Translate; however, what Google Translate produces is frequently imperfect (and sometimes downright incomprehensible), so there’s still a language barrier at work here that’s difficult for me to surmount.

And that’s just when it comes to the written word. There’s a not-insubstantial amount of video content about Yotteno floating around YouTube and TikTok, but again because of the language barrier, I’m unable to access most of the information within these videos. (YouTube’s auto-translate function is, to put it bluntly, a mess, and TikTok doesn’t have one at all.)

Additionally, much of the conversation around Yotteno occurred on social media, which has its own set of limitations: Some of the early posts have been deleted already; some of them I can’t access because of various accounts’ and pages’ privacy settings; and so on and so forth.

All of this is to say that I’ve done the best I can with what I have to work with — both in terms of what sources actually exist in the first place and with regards to my own limitations — but it’s possible (likely, even) that I’ve missed something somewhere, or misunderstood something, or what have you. Do let me know (gently, please!) if I’ve missed something — or, even better, if you’re Indonesian and remember when Yotteno was making the rounds, and you’d like to share your experience with the legend, feel free to reach out via our contact form, on social media, or by leaving a comment.

But, now that we’ve gotten that out of the way: Let’s talk about Yotteno.

The story goes a little something like this:

Yotenno Wants To Call You

In May of 2020 — the exact date is unclear — rumors began circulating Facebook’s Indonesian users concerning a mysterious profile belonging to someone (or something) calling themself “Yotteno.” Yotteno’s profile picture signaled something unusual about the profile right off the bat: A piece of art drawn in the Japanese kawaii style, the image depicted a white-faced young person with long, red hair — along with black holes for eyes and something black oozing from the character’s mouth. Kawaii, yes — but also just a little bit… off.

If you were to message the bizarre-looking Yotteno Facebook profile, the rumors stated, you’d proceed to have an equally bizarre conversation with its owner — one in which they’d send you a code you were clearly meant to crack. If you failed to solve it, you’d then be sent a string of ones and zeroes — something that looked like it could be a message written in binary, but may just have been a bunch of nonsense — followed by phrases like “I SEE YOU,” “I WANT [TO] CALL YOU,” and “YOU DIED TODAY.” Interestingly, these phrases were reportedly written in English, although the grammar would sometimes be incorrect.

Then, you’d supposedly receive a video call on WhatsApp from a mysterious number — +101 in the early tellings; 669-444-1925 in the later ones; and, still later, quite a few other numbers — whose profile image matched the one on the Facebook account. (This development was assuming, it seems, that you had WhatsApp installed on your phone. For what it’s worth, there were around 68 million monthly WhatsApp users in Indonesia as of 2020, which amounts to around 25 percent of the country’s population.) You could choose not to answer it, of course; if you did pick up, though, you’d supposedly see a real-life, monstrous version of the Yotteno illustration — one that was about as far from kawaii as you could get.

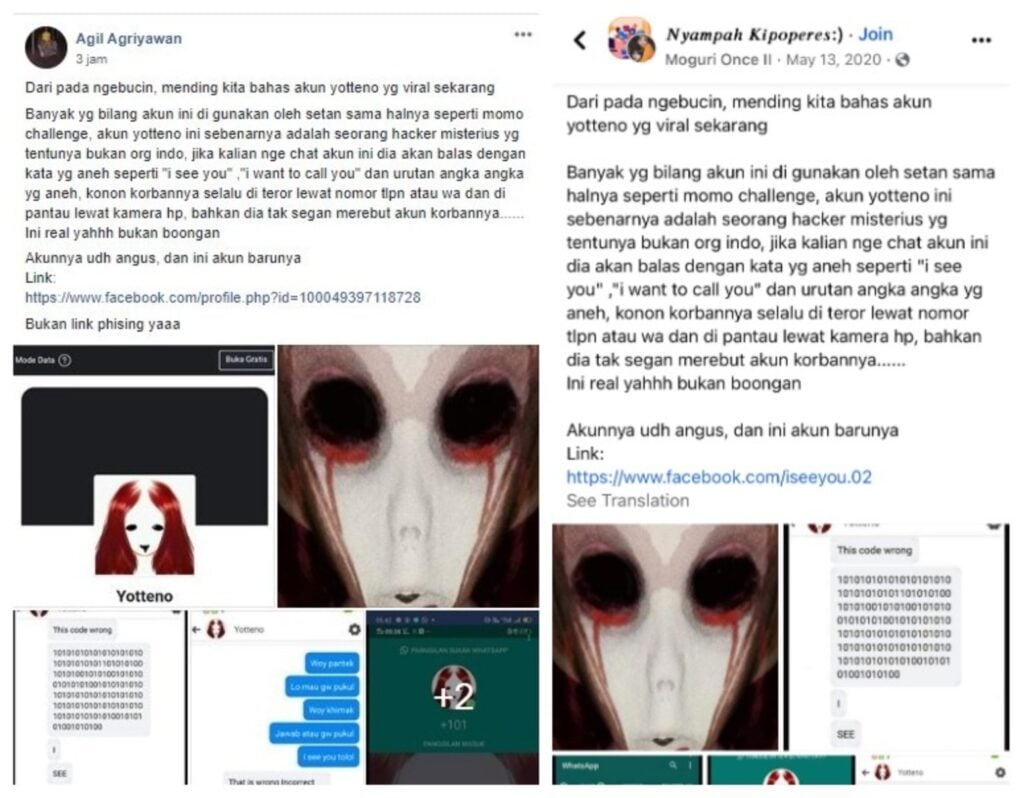

That’s how the story went originally. By May 13, however, things had taken a turn. At that point, those discussing the Yotteno phenomenon began claiming that Yotteno wasn’t a ghost, but a hacker — and that, by engaging with the Yotteno Facebook profile and WhatsApp number, you were opening yourself up to having your banking information and potentially your entire identity stolen.

This particular take is usually credited to a Facebook user named Agil Agriyawan, who created a post in a Facebook group around this time containing the following text:

Dari pada ngebucin, mending kita bahas akun Yotteno yg viral sekarang.

Banyak yg biland akun ini di gunakan oleh setan sama halnya seperti Momo challenge, akun Yotteno ini sebenarnya adalah seograng hacker misterius yg tentunya bukan org indo, jika kalian nge chat akun ini dia akan balas dengan kata yg aneh seperti “I see you,” “I want to call you” dan urutan angka angka yg aneh konon korbannya selalu di terror lewat nomor tlpn atau wa dan di pantau lewat kamera hp, bahkan dia tak segan merebut akun korbannya…

Ini real yahhh bukan boongan

Akkunya ugh angus, dan ini akun barunya (in some versions, Akun lma ny sdh hangus ini akun barunya)

Link: [here, there was a link to a now-defunct Facebook profile]

Bukan link phising yaaa“

The text was accompanied by a number of screenshots, as well, all seemingly depicting message exchanges with Yotteno on both Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp, a call log showing numerous inbound calls from Yotteno, and a screenshot of Yotteno’s illustrated avatar calling in on WhatsApp.

In English, the post translates approximately as follows:

“Instead of bucin, let’s talk about Yotteno’s viral account now.

Many say that this account is used by the devil just like the Momo challenge, this Yotteno account is actually a mysterious hacker who is certainly not Indonesian, if you chat with this account, they will reply with strange words like “I see you,” “I want to call you,” and a strange sequence of numbers, it is said that the victim is always terrorized via the phone or WA number and monitored through the cellphone camera, they do not hesitate to take the victim’s account…

This is real, not a lie

The old account is dead, this is the new account

Link: [here’s where that link would go again]

Not a phishing link!”

(“Bucin” is an Indonesian slang term usually used derogatorily, but lately being reclaimed; the group in which the post appeared was, it seems, centered around bucin. This tidbit is mostly irrelevant to the story, though.)

You’ll note, by the way, that I don’t have an exact date for Agil Agriyawan’s post; that’s because I’ve been unable to locate it. You can see a screenshot of it in this article at Kompirasi, though. We’ll come back to this point in a bit, by the way — hang tight.

In any event, this is also the point at which news coverage of Yotteno began: Starting May 13 and continuing for several days thereafter, a variety of Indonesian news and entertainment websites ran story after story about the mystery, mostly just repeating the same pieces of information gleaned from the same social media posts over and over and over again. Additionally, people now started claiming that they were reaching out to the WhatsApp nmbers associated with the legend themselves, deliberately, with the goal of getting in touch with Yotteno.

The discussion of the legend died out quickly, but the story is still an odd one. The details don’t always add up — or, perhaps more accurately, if they do, they don’t add up to the narrative they seem to want us to believe.

They might, in fact, reveal a very different story.

What’s Wrong With This Picture?

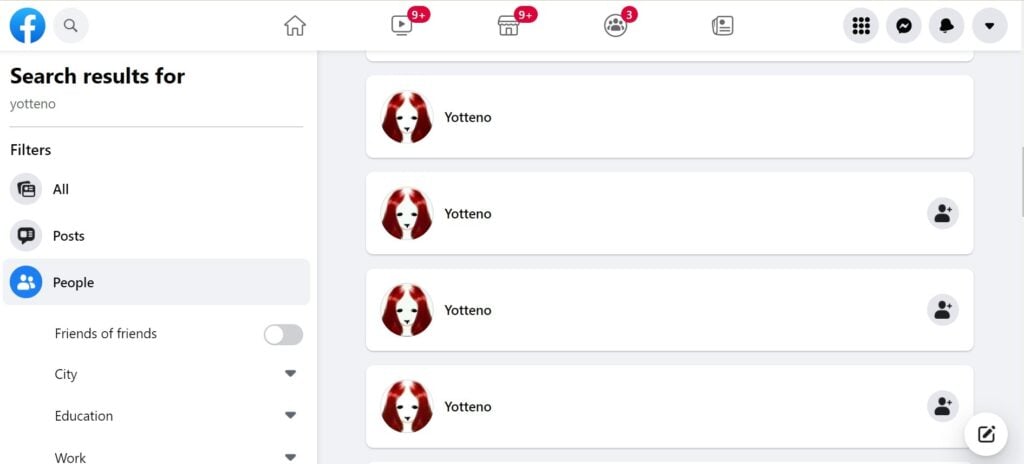

Let’s start with one of the story’s original claims: That Yotteno began life as a Facebook profile. There’s really no way to tell which Yotteno profile is the original one; there are so many copycats on the platform these days that trying to find the one that’s allegedly at the root of the story is like trying to find the proverbial needle in the haystack.

I did dig up two profiles that are commonly said to belong to Yotteno — profiles which are sometimes pointed to in social media posts about the ghost/hacker — but neither one of them is currently accessible. One of them, the “Iseeyou02” profile you’ll sometimes see mentioned in Facebook posts about the legend, is locked down; these days, it also just seems to belong to regular human. There’s no mention of Yotenno on the small portion of the profile available for the public to view. The other profile, meanwhile, simply “isn’t available at the moment,” according to the error message you’re greeted with if you attempt to view it. So, I can’t confirm whether or not either of these profiles really was the original Yotteno profile.

And that’s, of course, assuming there even is an original Yotteno profile. There may not be, although that’s another thing we’ll come back to.

But remember how Yotteno seems to have arrived on the scene sometime in May of 2020? And remember how I was unable to pin a date to the Facebook post from Agil Agriyawan that’s credited with the hacker angle? And remember how May 13, 2020 is when the discussion of Yotteno really seemed to kick up? That’s all notable. What follows is why.

I can’t pin a date on Agil Agriyawan’s post because, as I’ve already noted, I was unable to find a direct link to it. I’ve only seen screenshots of it within reports from Indonesian news sites. I did locate Agriyawan’s Facebook profile based on the distinctive, Lego minifig-style profile picture visible in the screenshots of his post (although I won’t link to the profile here, due to its being a personal profile, not a public page) — but hunting down the correct Facebook group in which he posted proved to be virtually impossible with the resources I have available. (There are so many bucin-oriented Facebook groups, y’all. So. Many.)

But you know what I can pin dates on? Numerous other posts that contain not just the exact same information, but the exact same text.

The text that makes up Agriyawan’s post, you see, can also be seen in numerous other Facebook posts published to various groups and pages — here, for example. And here. And here. And here. And here.

In all cases, the posts are essentially word-for-word reproductions of the post that’s so often credited to Agriyawan — maybe with a few changes; a different word choice here, the exclusion of a sentence there — but, more or less, the exact same thing.

That’s right: The text is a piece of copypasta. And since I can’t find a link for the post from Agriyawan, I can’t actually verify whether that post was the original source of the text, or just another copy-and-paste job — let alone whether the text is telling the truth, or whether its story is simply made up to frighten people. Interesting, no?

It’s also worth noting that all of those Facebook posts featuring the same piece of copied-and-pasted text were posted on the same day — which just so happens to have been May 13, 2020. In fact, I’ve not been able to find anything about Yotteno — anything at all — dated earlier than May 13, 2020; nor have any of the sources I have been able to find consisted only of the ghost story portion of the story, without mention of the hacker theory.

As was the case with Momo, I’m not entirely sure what to make of the fact that was no Yotteno discussion at all one day, and then, suddenly, there was an explosion of Yotteno discussion the next. But, tenuously: As far as I can tell, the Yotteno story arrived on the internet whole cloth, with all of the key elements — the Facebook profile, the WhatsApp call, the claim that it’s a ghost, and the claim that, actually, no, it’s a hacker — already present.

That’s… curious.

Furthermore, the Facebook page Dark Ice, which specializes in dark and weird news, posted what it referred to as a “clarification” on May 13 — the same day all those other posts appeared. According to Dark Ice, the Yotteno account is neither ghost, nor hacker; just “someone who feels bored and lonely.” Wrote Dark Ice:

“That person sent a message to DARK ICE and clarified everything. They deliberately locked their original account because many of you sent SPAM messages to them. If you find another account that uses Yotteno’s name, please block them.”

If this is true, then it’s possible that there may, in fact, have been an original Yotteno profile — and that it may have been the “Iseeyou02” profile I mentioned earlier. It all lines up: The profile as it currently stands is locked down and has removed any reference to Yotteno from the few portions of it that are publicly visible currently — so it’s not out of the realm of possibility that the person who owns the profile started the whole Yotteno phenomenon for the lulz, then backtracked and shut it all down when it started to spin out of control. Any Yotteno profile or activity that kicked up after that could easily have been done by unrelated randos who decided to ride Yotteno’s coattails to internet fame — which, in turn, helps to explain the sheer variety of WhatsApp numbers that have been seen in association with the legend.

Dark Ice also noted that many readers had contacted them about what happened when they tried to interact with Yotteno — which ultimately amounted to not much. “Since Yotteno’s appearance, many people have told me about this,” the page’s post stated. “Some of them claimed to have sent messages to Yotteno, but did not receive any response.” A few, wrote Dark Ice, claimed to have received replies in the “I SEE YOU” vein, while one person even claimed to have received a call, although they didn’t answer it due to fear.

I should repeat here that there is the possibility that I’ve missed something somewhere, or misinterpreted something, or that there are parts of the story that aren’t accessible to me which counter this idea. But from where I’m sitting, I’ve found no truly convincing evidence that Yotteno was truly as active as the stories claimed. I’ve not even really found convincing evidence that people have actually interacted with Yotteno; screenshots are easy to fake, and most of the videos I’ve seen allegedly texting Yotteno look like the kind of manufactured skits for which this particular corner of YouTube is notorious (see also: “3am challenges”).

I’ve only found people talking about Yotteno’s MO from a level of remove — the “this happened to a friend of a friend, I swear” framing that’s so common for urban legends, rather than any first-person accounts.

Yotteno feels, to me, like a manufactured story that ran amok when unleashed into the wild. But that doesn’t mean that it’s not interesting; indeed, there’s a lot here to unpack when it comes to the bigger picture.

Let’s widen the viewport a bit.

Variations On A Theme

Here’s what strikes me about Yotteno: The commonalities between it and other, similar stories. The Yotteno tale incorporates numerous tropes, themes, and motifs we’ve seen before in modern, internet- and technology-based urban legends — tropes, themes, and motifs which I’ve no doubt we’ll see again as stories of this nature continue to evolve.

I’ve mentioned this one a few times already, so let’s start here: Yotteno is often mentioned in the same breath as the earlier legend of Momo — and it’s little wonder why. Momo not only had become an international phenomenon just a year or so prior to Yotteno’s arrival; the “mother bird” creature’s earlier story variations also have much in common with the Yotteno story, and likely served as direct inspiration for Yotteno.

The first two iterations of the Momo phenomenon, which occurred in 2018, spread across Facebook and focused on the unusual conversations you might have if you messaged a couple of suspicious WhatsApp numbers. The Yotteno story, too, spread across Facebook — this time in 2020 — and involved unusual conversations pegged to suspicious WhatsApp numbers and profiles.

Arguably, though, Yotteno has more in common with the second iteration of the Momo story than the first one.

The first Momo variation just saw people who dared to message the (person behind the) monster receiving some weird, spooky, and occasionally NSFW/NSFL texts back, but nothing more. Speaking to Momo in this iteration was mostly harmless, if a little unsettling. The second Momo variation, however, added a “challenge” aspect to the story: It claimed that Momo, as I put it back in 2019, “didn’t just send you weird messages; she challenged you to perform a series of increasingly dangerous tasks and actions, culminating in self-harm and eventual suicide.” (Note that this wasn’t actually the case, though; there’s no evidence that the “Momo challenge” actually existed, or that anyone engaged in it. It’s basically the “Blue Whale Game” story in another form. But it quickly became part of the story, and the panic that surrounded it.)

It’s true that the Yotteno story doesn’t claim that the titular spook attempts to get people to perform dangerous actions — but it does claim that simply getting in touch with Yotteno is itself a dangerous action: If you speak to Yotteno, the legend warns, your bank accounts will be emptied and your identity stolen. Unlike the first Momo variation, speaking to Yotteno is not mostly harmless; it is, in fact, actively harmful to the people who dare to do it.

(For more on Momo, have a look at the deep dive into the legend I published in 2019.)

Speaking of the hacker theory, here, we again see shades of an earlier, phone number-based urban legend in the Yotteno story: That of the so-called “red numbers.”

The red numbers legend, which dates back at least as far as 2004, claims that answering phone calls from specific numbers — numbers which display as red on your device — can harm you in some way: Answering the call will make your phone explode; answering the call will cause brain damage to you; answering the call will transmit a virus either to your phone or to you yourself; and so on. None of that is possible, of course; the technology just doesn’t work that way. (This deep dive, which I also published in 2019, explains why.)

The Yotteno legend makes a similarly-formatted claim: That answering a call from Yotteno will grant hackers access to your phone and all the data you’ve stored on it — including important stuff like your banking information, your social media accounts and passwords, and so on and so forth. But, the same way you can’t be killed simply by answering a phone call — and despite what one YouTuber claimed in a video he posted to the platform on May 16, 2020 — your phone cannot be hacked simply by answering a phone call, either.

That’s not to say that phones can’t be used to “hack” you, of course; they can, and in fact often are — although not necessarily in the way the Yotteno legend would have you believe. Think of your garden variety phone scam: Say that someone calls you claiming to be your bank, and tells you that they’re investigating fraudulent activity on your debit card. They then tell you that they need you to confirm your account number, your PIN, your password, or any other sensitive information to them. If you give them this information yourself? I’m sorry, but you have just allowed yourself to be “hacked.”

Remember, banks never, ever ask you for this information over the phone. If you receive a call from someone asking you to reveal it, it is not your bank; it’s someone posing as your bank, and 100 percent a scam. But the key point here is that the person who’s scamming you can’t just get that information through the simple act of you picking up a phone call; you have to actually tell them what they’re asking for in order for them to pull their scam off.

But what about hacking in the traditional sense? You know, the whole “someone else gets into your phone and steals all your info from it” type of hacking? Yes, that can happen, too — but only if you do something that results in malware getting installed on your phone. If you’re texted a suspicious link and you open it, for instance? That’s a good way to get hacked; opening the link could start a download and install process which will put malware on your phone. If you’re asked to download a suspicious app or other piece of data? Same thing; still a good way to get hacked. Even connecting to an unsecured Wi-Fi network can allow someone to plant malware on your phone. Once that software is installed, it can very easily give someone access to all the data you’ve got stored on your device.

However, the Yotteno story includes no mention of anything that would result in malware getting downloaded and installed on your phone. The claim the story makes is that the hack happens if you just answer a call from Yotteno — and that simply can’t happen. The technology just doesn’t work that way.

The point here, though, is this:

The stories? They’re always about the same things, even as the details and the technology moves on.

The form changes; the fears remain the same.

What Now, Yotteno?

Ultimately, I don’t think Yotteno ever truly active, and if they were, it was only for a brief period — a day, maybe more, before they shut it down. But there are still a few mysteries that remain—including the details about the WhatsApp numbers associated with the legend.

As I mentioned earlier, the screenshots you’ll see floating around purporting to show conversations with Yotteno feature a huge number of phone numbers — which, again, suggests that most of them were copycats, or created by the people who posted the screenshots specifically to create a hoax. But one number pops up repeatedly — more often than any of the others: 669-444-1925.

This, you’ll note, is not an Indonesian number; it’s a U.S. number. Specifically, it’s a California number servicing the San Jose area; it’s based in Fremont County, in the city of Alameda. It’s not a landline; nor, though, is it a mobile phone number assigned by a mobile carrier. It’s a VOIP number — a Voice Over Internet Protocol number. That means that whoever is behind it doesn’t have to be in the United States to use it.

They could be anywhere.

And even though calls to it are unlikely to connect these days — an Italian YouTuber tried calling it in May of 2021, about a year after Yotteno’s heyday, and not only didn’t get through, but found the number didn’t even ring — well, that doesn’t necessarily mean Yotteno is gone for good.

Yotteno still might see you.

And Yotteno still might want to call you.

Consider yourselves warned.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And for more games, don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via MiRUTH_de (remixed by Lucia Peters), Didgeman/Pixabay; screenshots/Facebook (5)]

I love the Yotteno Story!

❤️❤️❤️