Previously: The Yokai Streets And Villages Of Japan.

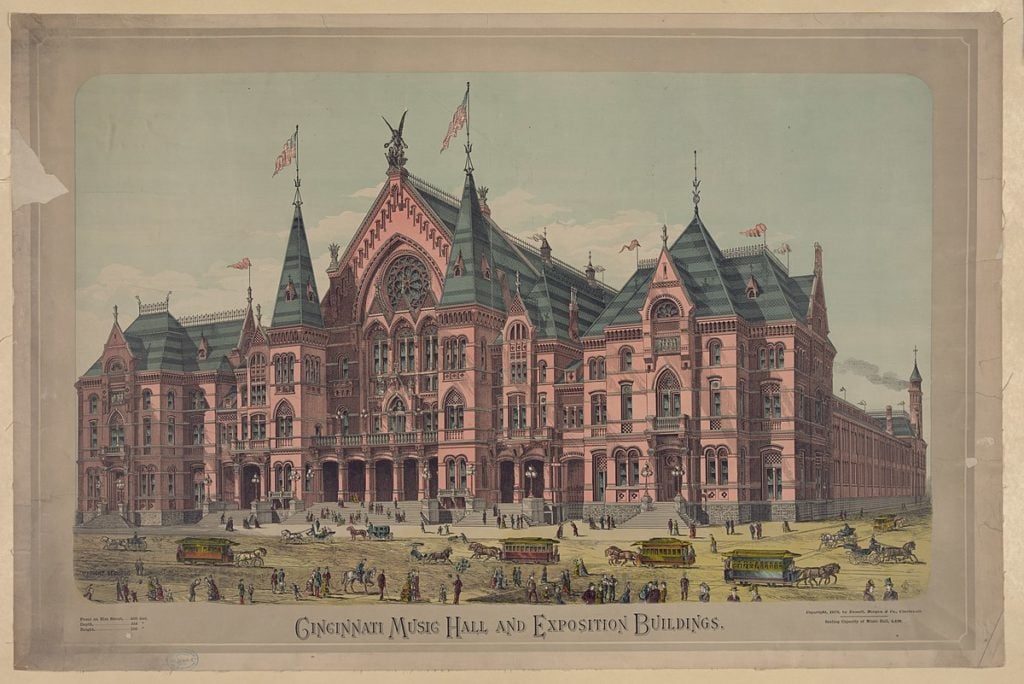

On Elm Street between 12th and 14th Streets in Cincinnati, Ohio, there’s a beautiful, red brick building in the High Victorian Gothic style popular during the mid-late 19th century. It has a gabled roof, pointed arches, and a stunning rose window. Nor is its beauty limited to the exterior; inside is just as lush — and it sounds just a lush, too. It’s a concert hall, you see — but not just any concert hall. It’s Cincinnati Music Hall, home to the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra, the Cincinnati Ballet, the Cincinnati Opera… and also a few ghosts. In fact, according to some, Cincinnati Music Hall is downright haunted.

The music hall’s official name is stylized without the article “the,” making it Cincinnati Music Hall, not the Cincinnati Music Hall. When shortened, the article is similarly missing; it’s Music Hall, not the Music Hall. But no matter what you call it, it’s worth noting that it’s not just a place that happens to have a bunch of unsubstantiated urban legends attached to it. There’s a lot of history behind Music Hall — and digging through that history actually reveals some very, very good reasons the building could be home not to one or two spirits, but a whole crowd.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

Assuming, of course, you believe in ghosts. Maybe you don’t — but many who have spent considerably amount of time within the concert hall’s walls would likely beg to differ.

A Palace Of Song

Legend has it that both the idea and a huge chunk of the funding for what would eventually become Cincinnati Music Hall came about as a result of… well, bad weather. According to a frequently-cited origin story, businessman and philanthropist Reuben Springer was in the audience during Cincinnati’s second-ever May Music Festival, held in 1875, when a massive storm interrupted the performance of selections from Wagner’s Lohengrin. The storm wasn’t just a passing patch of rain, though; it was so violent that it became difficult to hear the actual music, causing the music director, Theodore Thomas, to halt the performance.

The audio issues, seemingly, had rather a lot to do with the venue in which the concert was taking place: Both the 1875 May Music Festival and its predecessor, the 1873 festival, were held in the Exposition Hall — a building previously known as the Saengerhalle, which was originally built in 1869 before being enlarged in 1872. The trouble was, neither Saengerhalle nor the Exposition Hall was ever meant to be a permanent structure in the first place. Made of wood and with a dirt floor, the building, just six years old in 1875, was already in poor shape — and when the rain started beating down on the tin roof, it just proved to be too much.

Springer, it’s said, had a brainwave right then and there: Why not build Cincinnati its own, proper music hall? Clearly, there was a need for one — and a desire for one, too. So, he got to work.

Whether the rain storm story is true or not, Springer did, in fact, put the gears in motion to construct a music hall in Cincinnati almost immediately following the 1875 music festival. In a letter dated May 1875 and addressed to John Shillito, the wealthy owner of the Cincinnati department store John Shillito and Co., Springer laid out “some views about a Musical Hall building,” including plans for where it should be located, how it should be run, and — perhaps most importantly — how he proposed it should be funded. Springer wrote that, assuming the music hall could be constructed for about $250,000, he would donate $125,000 — half the required sum — as long as the land holding the hall was “secured in perpetuity for the uses of the Society at a nominal rent and free of taxation as before named” (“the Society” being an abbreviation of Springer’s proposed name for the music hall, the “Cincinnati Musical Hall Society”), and the other $125,000 was “secured by donations from our citizens.”

The conditions weren’t quite met; the city was only able to raise $106,000. But Springer rose to the occasion anyway, adding $20,000 to his original $125,000. He also offered $50,000 more to add to an additional fundraising goal of $100,000, to be used for additional wings meant for industrial expositions. All in all, Music Hall’s price tag came in at about $300,963; the exposition wings, meanwhile, cost about $146,332.

In 1876, the commission to design the hall was awarded to local architect Samuel Hannaford. The goal was for the music hall, which would be built upon the same site on which the Exposition Hall stood, to be completed in time for the 1878 May Music Festival — and, yes, they managed to achieve that goal. Cincinnati Music Hall opened on May 14, 1878 to a crowd of thousands while the May Festival Chorus and orchestra — conducted again by Theodore Thomas — played on.

But the Exposition Hall and Music Hall weren’t the first tenants to occupy that site — not even during Cincinnati’s then relatively short tenure. (What would eventually become the city of Cincinnati was established in 1788, after a combination of white European colonists and the Iroquois Confederacy forced indigenous tribes out of the area.)

In the early 1860s, the plot of land located on Elm Street between 12th and 14th Streets was owned by the city — circumstances which facilitated first the construction of the Saengerhalle, and then Music Hall itself. Prior to that, however — sometime around 1842 — the lot was home to the Cincinnati Orphan Asylum. And before that, it was home to something… else. Something a little spookier, and also a little sadder: According to the Friends of Music Hall preservation society, a map dated 1830 indicates that, prior to the orphanage, a potter’s field occupied the lot.

And we have the bones to prove it.

A Tragic History

In case the term is new to you, a potter’s field is what’s sometimes known as a pauper’s burial ground. It’s a public cemetery where, historically, people who are unable to pay for their own burial or simply people who die with no one to identify them or claim their remains are interred. The phrase itself is literally Biblical in origin; in the gospel of Matthew, the burial ground is purchased by the church with money given to them by Judas Iscariot — the same 30 pieces of silver for which Judas betrayed Jesus — because, as the priests put it, “It is not lawful to put [the coins] in the treasury, since it is blood money.” Continues Matthew 27:7, “So they took counsel and bought with them the potter’s field as a burial place for strangers.” The field in question is Akeldama in Jerusalem, which is rich in clay and is therefore believed to have once been a supply source for potters — hence, “potter’s field.”

Despite sounding somewhat Dickensian in nature, there are quite a few potter’s fields in the United States even now. What’s more, in recent years, there’s been a push to formally identify all of the previously unidentified occupants of these potter’s fields — something which is finally possible due to advances in DNA analysis technology and techniques. But, of course, identifying the “lost souls of America’s potter’s fields,” as Atlas Obscura put it in 2016, can only happen if we find the remains of those souls in the first place.

That’s why uncovering piles of bones when you’re getting started on a major construction project can actually be quite important discoveries — even though they can also be somewhat shocking if you’re not expecting it.

Such discoveries have been made multiple times over the course of Cincinnati Music Hall’s history — although, interestingly, it only started with the construction of Music Hall itself, not with its predecessor. (It’s thought that the Saengerhalle construction didn’t uncover any bones due to having been built without a foundation — that is, no digging occurred that would have unearthed anything from the ground.)

When construction on the new music hall began in October of 1876, it started, necessarily, with the demolition of the Exposition Hall. During the digging of the building’s foundation, “human remains” emerged from the ground, according to newspaper reports of the time; some of these reports stated that crowds stood by, observing, as “boxes were filled with skeletal remains,” although as the Friends of Music Hall note, it wasn’t uncommon for newspapers to exaggerate or sensationalize their reports to appeal to their reader base. (That is, we should probably take the reports with a grain of salt, as it’s possible — and, indeed, probable — that what actually happened wasn’t quite as dramatic as what the papers said happened.) These remains were later interred at Cincinnati’s Spring Grove Cemetery.

Then, in 1927, renovations and remodeling work unveiled more remains not once, but twice — three coffins were found in February and a 65-grave “Valley of Death” later that same year. Instead of being moved to a cemetery elsewhere in the city, these bones were all reburied where they were found. In 1988, drilling for a new elevator shaft revealed a whopping 200 pounds of bones, many of which were brought to the University of Cincinnati for study. And just recently, during restoration work undertaken between 2016 and 2017, more bones were discovered buried both under the orchestra pit and in the north carriageway. These remains were, like the first batch, re-interred at the Spring Grove Cemetery.

The thing is, no one is really quite sure how many people were buried in the potter’s field upon which Cincinnati Music Hall was built — and, as such, we also don’t really know how many people’s remains might be left, still sitting there in the soil underneath the structure.

What’s more, a handful of other sources have identified further events that may have affected the area surrounding the Elm Street lot. Cincinnati Magazine, for instance, pointed in 2015 to the 1838 explosion of the riverboat Moselle; the accident was so bad that, according to the Cincinnati Whig newspaper reporting the time, “heads, limbs, bodies, and blood were seen flying through the air in every direction.” (Again, it’s worth noting that newspapers of the era tended towards sensationalism — but the fact remains that the explosion was truly disastrous.) An additional article in the Cincinnati Commercial cited by Cincinnati Magazine claimed that the remains of those who died in this incident were buried in the potter’s field formerly located where Music Hall now stands. (It’s not clear whether this is actually the case, but it certainly does spice up the story somewhat.)

And in 2016, Cincinnati-based ABC affiliate WCPO pointed out yet another historical tragedy worth noting with regards to the music hall’s alleged haunting: A cholera epidemic swept the city in 1832, killing 832 people and leaving a huge number of children without parents or guardians. This, in fact, is positioned as the reason the orphanage was built on what would later become Music Hall’s lot. Furthermore, according to WCPO, the orphanage eventually became known as “the Pest House” due to having evolved into an isolation unit for patients at the nearby hospital with infectious diseases. The building was turned over the city after a new hospital was commissioned and built, therefore rendering the old hospital and the orphanage-turned-isolation-unit obsolete.

No wonder the place has a reputation for being haunted.

Haunted Happenings

The alleged activity spans much of the music hall’s history. Cincinnati Magazine quoted an old report from the Commercial extensively, including the observations of a former night watchman:

“The weirdest and strangest noises would occur at intervals all night. Rappings on the ceiling, under the floor, on the doors and windows, the sound of stealthy footfalls behind me, or of loud tramping before me; the crash of heavy timbers thrown from the ceiling of glass dashed upon the floor, of heaving bodies being dragged over the planking — these never ceased except during Exposition time.”

And although the watchman stated that he never saw any full-body apparitions, the spirits made themselves known to him regularly in other ways. He continued:

“They never touch me, but I always know when they are around, by an icy chill, a thrill as of electricity, a feeling like what the French call peau de poulet — goose flesh. They never annoy me now by mere knocking and rapping, for I have got used to it. So used to it that sometimes when people have really knocked at the door I didn’t open, because I thought it was only the dead that kept knocking, knocking, knocking.”

But lest you think, “But wait! Didn’t you say that newspapers back then tended towards exaggeration? How can I trust this account?”: Well, yes, I did, and ultimately, you probably can’t — but it’s worth noting that many more recent experiences have been documented, as well.

Erich Kunzel, who founded the Cincinnati Pops in 1965 and conducted the orchestra until his death in 2009, observed once, “They are definitely in this building, some sort of spirits. If anybody thinks I’m nuts, come here at 3:00 in the morning, 4:00 in the morning,” according to the Friends of Music Hall.

Patricia Beggs, the CEO and general director of the Cincinnati Opera, also described to the preservation society an experience relayed to her by another employee of the opera in the 1990s:

“One of our employees came down here one day during our season when we were dark and he brought his little three-year old son Charlie with him. They went out on stage and Charlie was enjoying pretending like he was performing and all of a sudden, he looked over and said, ‘Daddy, who’s that man in the box?’ That was [then Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra Music Director] Jesus Lopez-Cobos’ box, which is box 9, and his father Tom said, ‘’There’s nobody in the box, Charlie.’ ‘Yes, there is. He’s waving at me right now.’ And so with that, they packed up and left very quickly.”

And, yes, there’s a story from another night watchman, John Engst — this time dating back to 1987, according to CityBeat. Engst stated in his account that, one night, he heard music when he was alone in the building, but was unable to identify the source. “I re-entered the elevator and closed the doors,” Engst wrote, according to the Friends of Music Hall. “The music was still there and I’m starting to tingle now. I opened the rear of the elevator, entered the adjoining hall, no sound. Returning to the elevator to proceed to Corbett Tower and closed it up, the music was as beautiful as ever. For nearly two weeks I could not approach [the] elevator shaft on the first floor late at night without my whole body tingling.”

In 2009, CityBeat chronicled other accounts of spooky activity within the music hall’s walls, as well, including “shadowy figures [roaming] the halls and night and ghostly dancers … seen in the ballroom on the second floor.” In one account, a “young, pale woman in old-fashioned clothing” appeared to an exhibitor at a business fair, then turned transparent before disappearing entirely. Kitty Love, who at the time had been a member of Music Hall’s private police force for more than two decades, told writer John B. Kachuba, “I hear them when I’m on duty alone at night. Footsteps, doors slamming, and music playing, and I know I was the only one in the building.”

And, lastly, they say a picture is worth a thousand words — so take a look at two images captured by Matthew Zory, who is both a photographer and a musician who plays regularly at Music Hall (he’s the assistant principal bass of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra and the rhythm section bassist of the Cincinnati Pops) at the link here. Zory snapped the photos in 2016 during the most recent renovation of the building, writing in their captions on his Facebook page, “As you can see in these first two long exposure pictures, Music Hall clearly has some apparitions.” And, indeed, the images do depict something… odd: A sort of golden aura hovering around certain areas of the music hall.

Can it be explained by other means? Probably.

Is it spooky all the same? Absolutely.

Cincinnati Music Hall actively leans into its haunted reputation; the venue regularly hosts ghost tours, during times when it’s safe to do so.

Will you see anything if you go? Maybe; maybe not.

But keep an ear out for the faint strains of music — especially if it’s a day the orchestra has off.

You never know who — or what — might be responsible for it.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via islandborn/Pixabay; Wikimedia Commons, available under the public domain; Ohio Redevelopment Project/Flickr, available under a CC BY 2.0 Creative Commons license; Larsonj3/Wikimedia Commons, available under a CC BY-SA 4.0 Creative Commons license.]

Leave a Reply