Previously: Bic Camera Namba, Osaka, Japan

I was delighted recently to stumble upon a Wikipedia page — both on the English language Wikipedia site and the Japanese one — titled “Japanese haunted towns.” (For the curious, in Japanese, the phrase is “日本の妖怪街おこし.”) I realized upon a closer look that I was familiar with some of the places highlighted by the pages — and then I became even more thrilled at the fact that there was actually a name for these kinds of places (at least colloquially, if not officially). They’re what I’ve hitherto referred to as the yokai streets and villages of Japan — streets or, in some cases, entire towns which aren’t exactly haunted, per se, but which have been leaning into a yokai-based culture and identity as a means of revitalizing the areas and bringing in tourism in recent years.

Are they kitschy? Yes. Do I love them anyways? Absolutely. And, in fact, I’d argue that they’re even more fun for their kitsch. Basically, they turn their respective streets or villages into fun art installations honoring the traditions, folklore, and history of their given areas, and I love it. So, since none of us are likely to be traveling much anytime soon — especially us Westerners — here’s an “armchair traveling” look at a few of Japan’s delightful yokai streets and villages.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

First, a rough definition: “Yokai” (妖怪) is a term that functions as a broad umbrella for a variety of supernatural figures and creatures in Japanese folklore, mythology, and fiction. Yokai can be a lot of things, from ghosts to monsters and from spirits to, hilariously, inanimate objects which have somehow come alive. Many of the creatures that fall under the yokai umbrella can be described by more specific terms, too; for example, ghostly yokai are often more accurately described as yurei (幽霊). For that reason, you might see yokai rendered in English as anything from “hobgoblin” to “spirit.” The world of yokai is vast, and every corner of it is utterly fascinating.

Most yokai streets and villages — the kinds of places described by those Wikipedia pages as “Japanese haunted towns” — started really pushing the yokai angle in the late ‘90s or early aughts. And, much of the time, it succeeded, offering a slightly spooky, slightly silly, off-the-beaten-path reason to stop by some spots in Japan you might not otherwise think to visit.

Note that, as is often (and increasingly) the case with subjects I cover about which not much has been previously written in English, I had to conduct most of the research for this one via Japanese sources — and since I’m not fluent in the language, that means that I’m working through the imperfect lens of Google Translate. I do my best to make sure I’m parsing everything correctly, both through context clues and by consulting and comparing different sources for commonalities; however, it is possible that I may have gotten something wrong somewhere due to a translation error. I welcome corrections from folks who are either familiar with these places or who speak the language fluently, so please do let me know (nicely, please!) if anything needs updating.

So, with that said: Let’s go yokai-hunting!

Oboke Yokai Village, Yamashiro-cho, Miyoshi-shi, Tokushima Prefecture

The town of Yamashiro-cho in Tokushima Prefecture (not to be confused with the Yamashiro-cho in Kyoto) doesn’t technically exist anymore — although it does have a long and somewhat complex history. Originally founded centuries ago, it was established as Yamashiro Tanimura in 1888 following the Great Meiji Consolidation and enactment of the Shisei-Chosonsei system of cities, towns, and villages; then, in 1957, it was Yamashiro Tanimura was merged with Sanmyo Village to form Yamashiro-cho. But in 2006, towards the end of the Great Heisei Consolidation, Yamashiro-cho was merged yet again with a number of surrounding villages to form a city: Miyoshi-shi.

Within its gorges and valleys, Yamashiro-cho also has a rich tradition of yokai legends — and in 1998, a local volunteer preservation group began a revitalization project incorporating these legends in order to bring a bit of life and tourism back to the area. Thus, the establishment of Yamashiro Oboke Yokai Village (山城大歩危妖怪村): A place located in the beautiful Iya Valley where visitors can become one with the yōkai. Among the attractions in the area are the Yokai House and Stone Museum (妖怪屋敷と石の博物館), also (and perhaps formerly — due to translation difficulties, it’s unclear to me which) known as Roadside Station Oboke (道の駅大歩危内), a small museum where visitors can learn of the legends associated with the area; the Yokai Highway (妖怪街道), which features sculptures of yokai set in their natural habitats; and an annual yokai festival held each year in late November.

Specifically, the area lays claim to the legend of the konaki-jiji (子泣き爺), a yokai that looks like a little old man, but cries like a baby at night to lure in human victims. Once he has convinced a human to pick him up, he then grows heavier and heavier until he crushes them. There’s some debate these days over whether the konaki-jiji actually does originate in Tokushima, or even that the legend ever truly existed in the first place; although it was documented by famed folklorist Kunio Yanagita, modern researchers have theorized that it’s a much more recent story that may have emerged from a combination of other legends. The figure is known primarily for its appearance in the Shigeru Mizuki manga GeGeGe no Kitaro (ゲゲゲの鬼太郎). Still, though; today, it’s purported to be one of the defining legends of the area — and a stone statue of konaki-jiji stands on the Yokai Highway as a testament to that fact.

Watch a video showing Oboke in all its yokai glory here.

Yokai Street, Kyoto-shi, Kyoto Prefecture

Located on Ichijo-dori (一条通) between Nakadachiuri-dori (中立売通) and Nishioji-dori (西大路通) and officially called Taishogun Shopping Street (大将軍商店街), the city of Kyoto’s Yokai Street (妖怪ストリート), or Monster Street, has an adorable surprise for those who choose to do their shopping there: Around 30 small sculptures and statues of yokai occupy the corners and sidewalks outside the stores. As you stroll down the street, you’ll meet such creatures as shokupan-jijii (食パンじじい), who guards a bakery and warns you of what will happen if you don’t eat all of your bread; Shizuka-nyan (しずかにゃん), who hangs out beside a kimono shop; and a chochin-obake (提灯お化け), a yokai that used to be a paper lantern.

Like Oboke Yokai Village, Yokai Street is the result of a relatively recent initiative intended to revitalize the area. Started in 2005, the initiative has not only dressed up the street with yokai sculptures, but also launched two yokai-themed events: Each year, both a ghost flea market called Mononoke Ichi, and a yokai costume parade, called Ichijo Hyakki Yagyo, take place during the summer.

My favorite part about this particular yokai spot is the origin story that goes along with it: Legend has it that one day during the Koho Era (964 through 968 C.E.), a city-wide cleaning initiative resulted in many old tools being tossed out and left by the side of the road—but the tools, it turned out, weren’t having it: Angry at having been discarded so callously, they transformed into tsukumogami — yokai which are tools which have gained a spirit — and marched down the street in a Hiyakki Yagyo (百鬼夜行), or Parade Of One Hundred Demons. The sculptures and statues lurking outside the shops on Yokai Street are meant to represent these tsukumogami. Yes, the story is manufactured — but it’s still delightful.

Watch a delightful video showcasing the wonders of Kyoto’s Yokai Street here.

Tono-shi, Iwate Prefecture

Tono is so well-known for its folkloric tradition that it’s got its own collection of tales: Tono Monogatari (遠野物語), collected and published by Kunio Yanagita (see also: Oboke Yokai Village) in 1910. Not all of these tales center around yokai, of course — there’s more to folklore than just ghosts and monsters — but many of them do, because, well… even if they’re not all there is to folktales, ghosts and monsters do often make up a large portion of them.

If you go to Tono, you’ll definitely want to keep your eyes peeled for one yokai in particular: Kappa (河童) are said to find the area quite comfortable. Reptilian and with shells on their backs, but bipedal and with beaks similar to a bird’s, kappa are, as the Japan Times noted in 2014, often referred to as “water sprites” in English — due, naturally, to the fact that they live in and around the water — but functionally behave more like “the carnivorous troll under the bridge in the Norwegian fairy tale ‘Three Billy Goats Gruff.’” They’re mischievous, but also a little dangerous; they love to eat cucumbers, but if they can’t get a hold of those, they might try snacking on a human child instead. If you encounter one, though, it’s said that bowing to it might help you escape; polite to a fault despite its tricky streak, the kappa will be compelled to return the bow, spilling out the fluid held within the indentation on the top of its head that gives its power.

Kappa can (allegedly) specifically be found at the Joken-ji temple (常堅寺) in the nearby Kappabuchi Pool (カッパ淵). According to WAttention Magazine, you can pick up a “Kappa Hunting License” as a souvenir from the Tono Tourism Association at the Tourism Information Center near Tono Station or at Denshoen Park near the pool itself for just a couple hundred yen; you also might be able to say hello to Harou Unman, who hunts kappa at Kappabuchi regularly.

Beyond kappa hunting, you might also want to check out the Tono Folktale Museum; it’ll give you a great overview of the rest of the folkloric landscape of the area, as well as introduce you to Kunio Yanagita, if this is your first time encountering his work.

Watch a video that is literally 10 hours of a cucumber hanging over Kappabuchi Pool in an attempt to catch a kappa here.

Mizuki Shigeru Road, Sakaiminato-shi, Tottori Prefecture

Remember Shigeru Mizuki? The manga artist whose long-running, yokai-centric series GeGeGe no Kitaro featured, among others, the konaki-jiji? Well, he grew up in Sakaiminato in Tottori Prefecture — and now, there’s a yokai street that stands in the city as a tribute to him and his work.

Mizuki was born in 1922. His artistic talent became apparent when he was a child, but in 1942, he was drafted into the Imperial Japanese Army. The only surviving member of his unit, he eventually made it home in 1946. After working a variety of odd jobs for many years, he published his first manga, Rocketman, in 1957 — and then, in 1960, he began work on a manga adaptation of a kamishibai (紙芝居), a form of puppet-based street theatre, called Hakaba Kitaro (墓場鬼太郎) or Kitaro Of The Graveyard. This manga focused heavily on yokai and other piece of Japanese folklore — and when it began serial publication in 1965, it would become a hit. In 1967, it received the name by which it’s been known ever since: GeGeGe no Kitaro.

Construction on the road honoring Mizuki’s work, Mizuki Shigeru Road (水木しげるロード), began in 1989 with loads of public support. When it opened in 1993, about 23 bronze statues featuring his yokai designs from GeGeGe no Kitaro were completed; more have arrived ever year since, with the number now totaling 177. Figures represented include betobeto-san (べとべとさん), who gets his name from the sound his wooden clogs make as he follows you in the dark; Sunakake-baba (砂かけ婆), also known as the Sand Witch; and, of course, Kitaro of the Graveyard himself.

Mizuki passed away in 2015 at the age of 93 — but his legacy is certainly alive, well, and haunting Sakaiminato still.

Watch a video tour of Mizuki Shigero Road here.

Yokaichi-shi, Higashiomi-shi, Shiga Prefecture

Like Yamashiro, Yokaichi doesn’t exist on its own anymore; it merged with several other towns in the mid-2000s to become a city — in this case, the city of Higashiomi. But it still honors its local flavor, including something unique about its name: As Philbert Ono noted at his Shiga blog in 2013, Yokaichi is written using the 八日市, meaning “Eighth Day Market” (that is, the town was named for the fact that its market was traditionally held on days of the month with 8 in the date) — but it can also be written as 妖怪地, meaning “Land of Yokai.” Accordingly, the Yokaichi Shotoku Matsuri (八日市聖徳まつり) festival, which is held every July, leans heavily into its yokai theming.

A local group called Honaikai (ほない会) began developing Yokaichi’s yokai culture around 1999, with several maps noting the area’s “mysterious spots” appearing in 2002. The matsuri, however, has been held for much longer — I believe since 1969, if I’ve understood my sources and done my math right. The matsuri features a night market (本町土曜夜市), a Hiyakki Yagyo costume parade (not unlike the one held on Kyoto’s Yokai Street), and a dance event called Goshu Ondo So-Odori (江州音頭総おどり). The festivities center largely around a local spirit called Gao, an ogre-like creature who is said to eat children who misbehave.

Watch a video of the 2013 festival here.

Ome-shi, Tokyo-to

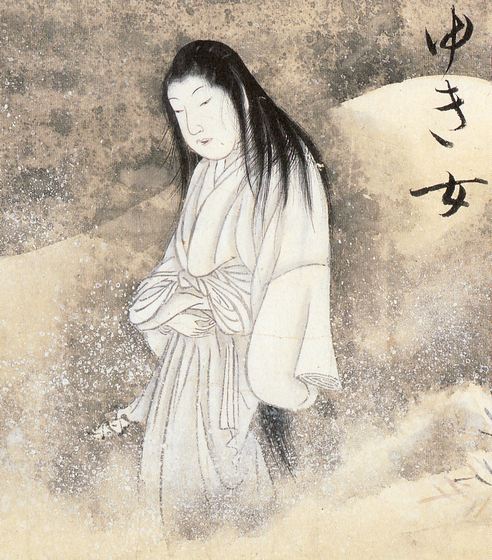

In recent years, city officials have been promoting the Ome area as “Tokyo’s center of folklore,” according to one news reported from 2012, with the yuki-onna (雪女) or “snow woman” story serving as the central focus of the initiative. Numerous version of the legend exist, but they all center around a woman who, it turns out, is essentially made of snow — and, one way or another, ends up melting or otherwise vanishing when introduced to something like a hot bath by her mortal husband.

But wait — if yuki-onna is a creature of the cold and snow, what’s she doing in the Tokyo metropolitan area?

That’s an interesting question. As Zack Davisson notes over at Japanese folklore-focused website Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai, yuki-onna tales do hail primarily from the snowy north of Japan, namely in Aomori, Iwate, Miaygi, Yamagata, Nagano, and Nigata. But, observes Davisson, she can also be found almost everywhere else in Japan, too. Indeed, as he puts it, “There are few prefectures in Japan without at least one yuki-onna story.” (The exceptions are Okinawa and, oddly, Hokkaido.) According to Davisson, the Tokyo connection likely came about via Lafcadio Hearn’s (likely highly embellished) 1905 yuki-onna story, the source for which was likely a father-daughter duo from Ome who served as domestic workers in Hearn’s Tokyo home.

In any event, Ome has been leaning into its version of the yuki-onna story recently; indeed, stamp rallies are sometimes held challenging participants to visit a map’s worth of folklore-related spots around the area, including Chofu Bridge, which plays host to a monument to the yuki-onna.

But yuki-onna isn’t the only folktale or yokai legend that Ome has been laying claim to lately; there are so many that people have begun conducting yokai tours of “psychic hot spots” in the area. You can watch a video of one such exploration here, although be warned that it’s in Japanese and only has auto-generated (and therefore often very garbled) subtitles in English.

And there you have it! Six yokai streets and towns in Japan worth visiting, either in person when it’s safe to do so again, or via the wonders of the internet from the comfort of your own couch. They’re probably not the only ones that exist, but they’re the ones that I was able to dig up the most information about, so, if anything, they’re a good place to start.

Where will you go?

What yokai will you seek?

What stories will you hear — and what stories will you tell?

Only you can answer that for yourselves. Keep an open mind, have fun, and travel well.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via sprklg/Flickr, available under a CC BY 2.0 Creative Commons license; Sawaki Suushi/Wikimedia Commons, available under the public domain.]