Previously: The Missing Man In The Paris Catacombs.

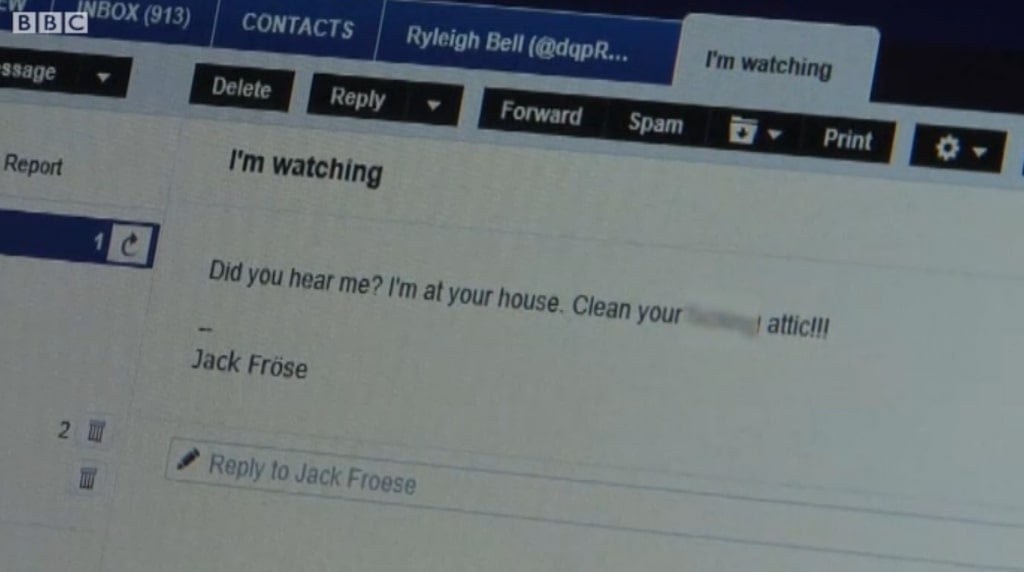

The message appeared in Tim Hart’s inbox one night in November, 2011. Addressed from Hart’s friend, Jack Froese, the email had a somewhat ominous subject line; it read, “I’m watching.” The text of the email was similarly menacing, reading, “Did you hear me? I’m at your house. Clean your fucking attic!” But the tone of the message wasn’t what made the email unsettling; Hart and Froese had been friends for 17 years and were well accustomed to each other’s sense of humor. No, what made Tim Hart’s stomach drop was one simple fact:

Jack Froese had been dead for five months.

On June 10, 2011, Froese, who lived in Dunmore, Pa., suffered a heart attack at his home. The loss was — and is — deeply felt by his friends and loved ones; quick with a snappy comeback and a master of sarcasm, he was well-known for his sense of humor and his kindness. His obituary, which ran in the Scranton Times on June 14, 2011, described him as having a “bigger than life” personality. He loved his kids, then three and four years old; he loved music; he loved tattoos and tattoo artwork; he loved motorcycles; and he loved animals. “He could make you laugh even on your worst day,” read the obituary. “He will be deeply missed by all whose lives he touched.” He was just 32 years old.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

And then, months later, the emails came, according to a report by the BBC in 2012. “One night in November, I was sitting on my couch, going through my emails on my phone and it popped up: ‘Sender: Jack Froese,’” Hart said to the news outlet. “I turned ghost white when I read it.”

It’s the attic reference that made the message so cryptic — because according to Hart, it was “a point that only Jack and I could relate on.” The second to last time Froese had visited Hart at his home prior to his death, they had gone up to the attic together. “We were up here looking at what we would have to do if we ever wanted to finish it,” Hart told the BBC. “And the floor is just dusty, and he’s like, ‘Better clean this attic before I get up here.’” There was no else in the attic with them at the time; “Just he and I up here — that’s it,” said Hart.

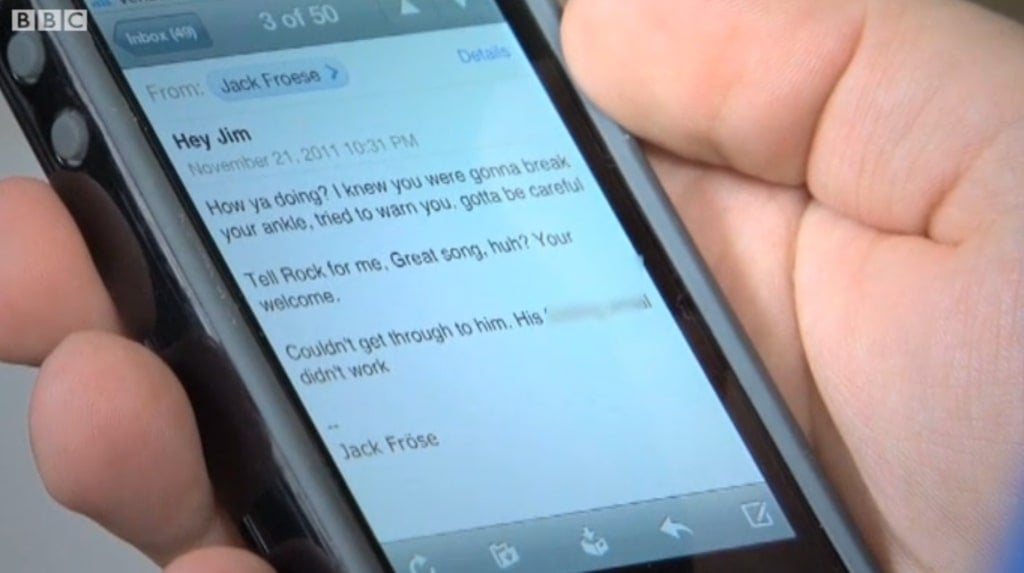

What’s more, Hart wasn’t the only person who received this kind of email from Jack Froese that November — or at least, an email from Jack Froese’s account. Froese’s cousin, Jimmy McGraw, also found something odd in his inbox on Nov. 21 at around 10:30pm. The subject heading was “Hey Jim,” and the message read as follows:

“How ya doing? I knew you were gonna break your ankle, tried to warn you. Gotta be careful.

Tell Rock for me. Great song, huh? Your [sic] welcome.

Couldn’t get through to him. His… email didn’t work.”

McGraw had, in fact, broken his ankle the week prior as he was heading out the door to work — but he’d seen or told very few people about the accident.

You can imagine the question that rose up from these odd and mysterious messages: Was it possible? Could Froese himself somehow be communicating with his friends and loved ones after his death?

The answer was, is, and remains: We don’t really know.

Exactly what happens to our online presence when we die remains a subject of great interest, although the policies for specific services have been slow to arrive. Facebook, which launched in 2004, only began offering the option to memorialize profiles and pages belonging to deceased users in 2015; Gmail did a little bit better, launching in 2004 and only (or, y’know, “only”) taking until 2013 to roll out the “Inactive Account Manager” protocol; but Twitter has lagged behind, offering only two options: To deactivate the account upon the provision of verified proof of death, or to leave the account as is — which means that, should anyone else gain access to it, they can tweet freely from it.

Indeed, if we were to apply Occam’s razor to the situation surrounding Froese’s emails, that’s the explanation for the account’s continued activity that’s most easily assumed: Rather than Froese’s spirit sending the messages “from beyond the grave,” as it were, someone else could have gained access to Froese’s account. The means by which this access could be granted are many; someone could already know the password to the account, or they could have hacked their way, or they could have requested and been granted access by the service itself. Odd behavior emanating from email addresses and social media isn’t an uncommon occurrence; you only have to look at what happened to the email and Twitter accounts of journalist David Carr following his death in 2015 to see that: They were famously taken over by spambots, both shocking the general public and distressing those who knew and worked with the man.

But there’s also this: If you want access to a deceased loved one’s account or simply to shut it down, many services will make you jump through an extraordinary number of hoops to do so. On the one hand, that makes sense; you wouldn’t want it to be easy for someone to shut down someone else’s account as a prank or a malicious act if that person is, in fact, still alive. At the same time, though, it’s also problematic: Grieving people (understandably) may not have the wherewithal to put themselves through everything that’s required to access or close down the accounts of someone who is no longer with us. Knowing that, then, is the idea that someone else could have gained access to Jack Froese’s email as plausible as it first seems?

Maybe… but maybe not. Indeed, many of those who have received emails from Jack Froese after his death aren’t convinced that the messages are actually coming from someone else, reported the BBC. According to Hart, some of them banded together to look into the possibility — but they don’t believe anyone else knew Froese’s password, nor do they suspect his account was hacked.

Besides, even if the messages were coming from a prankster, how do you explain their content — the references to moments no one else knew about?

Could the emails have been set up by Froese while he was still alive and scheduled to send out later on? Again, it’s a possibility; as Vice reported in 2016, there are a plethora of apps and services that will do just that. These kinds of services usually depend on their users checking in periodically to confirm that they’re still alive; if they miss a check-in and another predetermined space of time goes by without response, they’re assumed to be dead and the messages are sent automatically.

But although there’s record of such services existing long prior to Froese’s death — the Last Message Club received a writeup in the Independent in 2009, for example — this explanation, too, falls short. McGraw’s broken ankle occurred long after Froese’s death, so — unless we’re looking at one heck of a coincidence — there’s no way Froese would have known to make such a reference so many months down the line.

Whether or not you believe the emails are supernatural or simply natural depends, of course, on how you feel about ghosts more generally; I’m inclined to believe that we’re dealing with a prankster or hacker, myself, but that’s just me.

Froese’s loved ones, meanwhile, are happy just letting the messages speak for themselves. “We spoke to his mother,” said Hart to the BBC, “and she told us, ‘Think what you want about it, or just accept it as a gift.’” Added McGraw, “I would like to say Jack sent it, just because I look at it as, he’s gone, but he’s still trying to connect with me — he’s still trying to tell me things, to move along, to feel better.”

In this respect, the emails almost feel akin to the Otsuchi phone booth: Whether or not there’s someone on the other end remains to be seen; however, for those who are grieving a painful loss, there’s still comfort to be found in it.

Even though I don’t believe in ghosts, I do believe in the power of memory. And memory gives us life — whether or not we’re still technically around.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via anaterate, pedrofigueras/Pixabay; screenshot/BBC (2)]

Leave a Reply