Previously: Sad Satan.

(CW: Homicide, suicide, accidental death.)

In 2011, a short film was posted to the r/videos subreddit. “This is a true story about the internet,” it began. But that wasn’t all — it was also, the opening narration said, “the story of a treasure map, and a murder.” Called “Internet Story,” the film had been written and directed by Adam Butcher and posted to Vimeo in 2010 — and, as eerie and unsettling as it was, it looked like it could be real.

It wasn’t, of course; indeed, Butcher was fairly upfront about the film’s fictional nature right from the start. Yes, he laid out bits and pieces spread across the internet to enhance the storytelling, all of which blurred the lines quite a bit — but we’ve pretty much always known that the story itself isn’t real. If anything, the inclusion of a credits reel noting that the film was written and directed by Butcher, as well as identifying the voices heard in it — Shaun French and Duncan Wigman, with French portraying the narrator and Wigman playing the YouTuber character Fortress — lays out the story’s reality in no uncertain terms.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

But those bits and pieces also highlighted the kernel of truth at the center of the film — and, indeed, Butcher noted in a short interview with CBS at the time “Internet Story” went viral that his inspiration for the whole venture was “a side of the internet that we’ve all probably experienced at some point. The way searches can become rabbit holes into strange places. The sometimes faceless, heart-breaking loneliness of the internet. The sense of people talking but not connecting.”

All of this got me thinking: The murderous treasure hunt of “Internet Story” may never have happened — but has anything similar ever actually occurred in real life?

The answer, it turns out… is yes.

To an extent, at least.

Let’s explore.

“This Is A True Story About The Internet”

“Internet Story,” which you can watch here, isn’t quite found footage, but it’s not a typical narrative film, either. If I had to define it, I’d probably call it a mockumentary — but the beauty of it is that it sort of defies definition. Told through a combination of animation, narration, screenshots, still images, and, yes, found footage, it tells… well, it tells an internet story — a story that could only exist on and because of the internet.

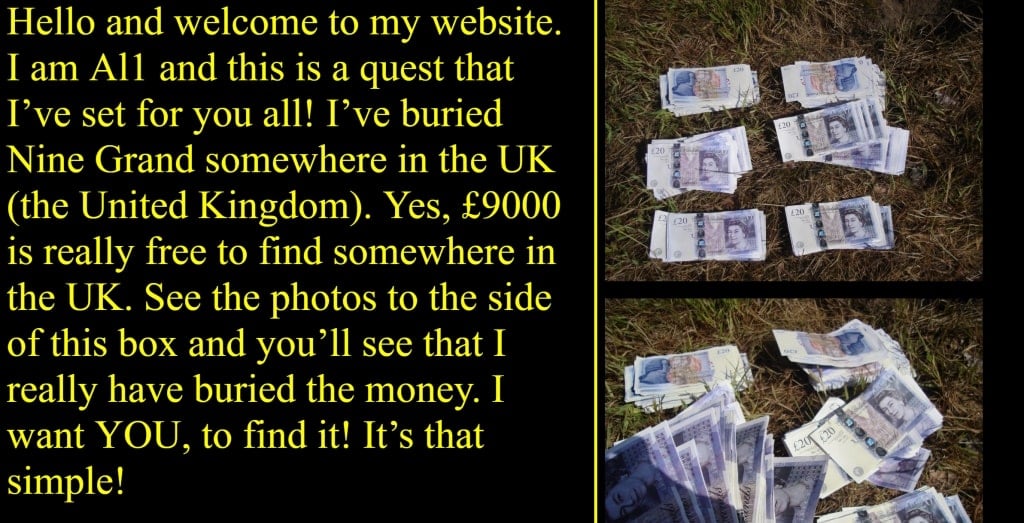

According to the film, someone going by the handle Al1 published a website on April 22, 2005 laying out a challenge called Al1’s Nine Grand Quest: Al1 — presumed by the narrator of the film to use he/him pronouns — said he had buried £9,000 somewhere in the UK. Solving Al1’s elaborate chain of puzzles would reveal where the money had been hidden — and if you found it, it was yours. Basically, it was a scavenger hunt with a big-ticket prize. As the narrator notes, “not that many people were paying attention” to Al1’s puzzle — a shot of the visitor counter reads a mere 25 hits to the page — but one person was paying attention: A YouTuber going by the name Fortress. Beginning a few weeks after Al1’s website first appeared, Fortress began documenting his efforts to solve the puzzle. He even seemed to be on the right track; however, like Al1, his videos mostly went unnoticed: A shot of the view count for one of them reads just 29.

Fortress eventually discovers that he has to take a trip to Wales in order to further his quest — and from there, things go from zero to 60 incredibly fast. There’s an enormous piece of the puzzle Fortress has missed; if he had followed certain patterns present throughout all the clues and taken a closer look at the final one, he would have seen a message from Al1 — one that reads, “I’ve been alone for so long. But you’ll find me now.”

Two days after Fortress departed for Wales, claims the film, a news item was published on the BBC’s website: A body of a man had been found in a Welsh field. Presumably, it was either Fortress or Al1.

Trouble is, we don’t know which. Or what happened in that field that may have led to a dead body in the first place.

“Internet Story” is all presented quite convincingly; however, we can debunk most of it pretty quickly, largely by tracking the film’s production timeline. The early development of “Internet Story” is a little difficult to pin down these days due to Butcher having substantially redesigned his website in the intervening years; however, viewing the page through the Wayback Machine can provide a rough timeline. The earliest mention I’ve been to find of “Internet Story” in Butcher’s News section is dated April 30, 2009, at which point the film was already in production. “We’re making some great progress with ‘Internet Story,’ having just finished recording the vocals,” wrote Butcher. “We went through the lines in almost microscopic detail but we got some great performances in the end, and still finished early! Rather unconventionally, we’re going the visuals after the audio, so we’ll be filming very shortly.”

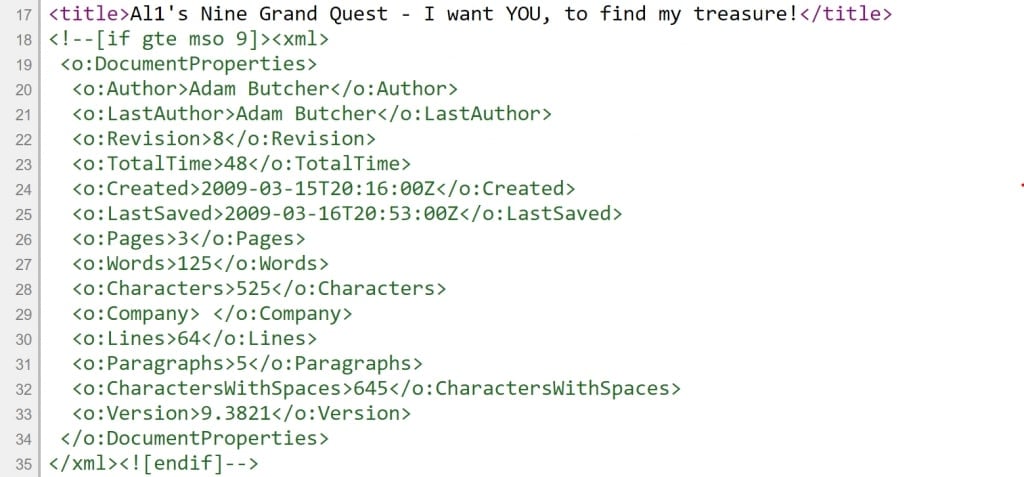

In June, he dropped the first “real life” clue: A link to the Al1’s Nine Grand Quest website. “Was very surprised recently when my ‘Internet Story’ research brought up a strangely similar — but actually real! — website. Here it is: Al1’s Nine Grand Quest,” he wrote. “Hmm. I’m very much considering adapting the script to include this sort of thing. I’ll let you know how it goes.”

By July 19, 2009, the film had entered principal photography; it was completed around Aug. 17, with the audio edit being done and the visual edit “rocketing along behind it.” The film was finally finished in April of 2010 and premiered a few months later in August.

The Al1’s Nine Grand Quest page, which was made using Angelfire, is still live, by the way — and if you take a look at the source code, you can see who actually created it and when: Its author is listed as Adam Butcher, and the page was created on March 15, 2009. Additionally, Fortress’ YouTube channel was created on Aug. 15, 2008, with the first upload — “I solve the £9000 quest! #1” — arriving on May 16, 2010. Both dates are long after Fortress was meant to be solving the puzzle, so again, although Butcher went above and beyond in actually creating Fortress’ account and videos, we know that they didn’t exist during the 2005 timeframe claimed by “Internet Story” itself.

But even if the plot is fabricated, the story itself? Well, that’s real. Or at least, it could be.

On The Hunt

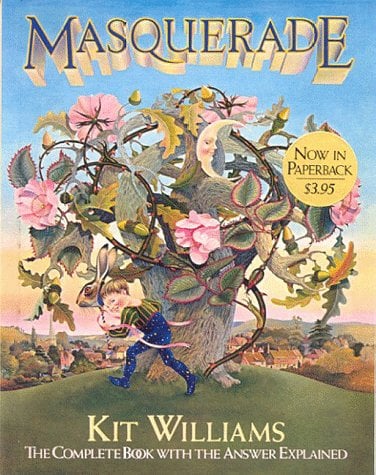

Treasure hunting as a practice has existed for centuries; it’s ethically dubious, but searching for and salvaging items of historical and/or financial value is nothing new. The same is true of scavenger hunts — according to Smithsonian Magazine, we can trace them back centuries to traditional folk games. But “armchair treasure hunts” — which is probably the closest analog to what Al1’s Nine Grand Quest really is — are a relatively recent invention: The 1979 book Masquerade is typically credited with being the first.

We talked a bit about Masquerade and other armchair treasure hunts last year in relation to the podcast Rabbits, but in case you need a reminder, these real-life adventures took the form of picture books with a secret: Embedded within them were deeply complex puzzles and riddles, which, when solved, yielded an actual prize worth many thousands of dollars. Armchair treasure hunts have rarely ended in the way they were intended to; Masquerade, for example, ended in scandal, and many others — 1982’s The Secret, 1993’s On The Trail Of The Golden Owl, 1998’s The Merlin Mystery, and more — have never been solved.

They did, however, get people up and about and exploring the world, despite their sedentary-sounding name — and in that sense, they’re very much the precursors to Al1’s Nine Grand Quest. Indeed, as the decades wore on, they began to change form somewhat. The 2002 television show Push, Nevada doubled as an armchair treasure hunt, for example — and beyond the world of published picture books, geocaching has been steadily on the rise since 2000.

Geocaching has its roots in letterboxing, an outdoor pursuit that dates back to the Victorian era. The very first — and, for quite some time, the only — letterbox was installed at Cranmere Pool in Devon, UK in 1854. Placed there by Dartmoor guide and walker James Perrot, it included Perrot’s calling card and instructions for others to leave their own if they pleased. A 1998 Smithsonian article brought the practice to North American attention, and today, the letterboxing community has spread far and wide. Letterbox locations are hinted at with clues; then, when letterboxers solve the puzzles and find where the boxes are hidden, the both stamp the box’s logbook with their own unique stamp and stamp their own logbook with the box’s stamp (it leaves the record of their find in not one, but two places). Then they hide the box again, leaving it for the next explorer to find.

Then, on on May 2, 2000, Selective Availability was removed from the Global Positioning System — or GPS, as it’s more commonly known — greatly improving its accuracy and inadvertently prompting the rise of geocaching. Computer consultant Dave Ulmer is generally credited as placing the first geocache; in order to test the accuracy of the newly-freed GPS, he created “The great American GPS Stash Hunt” by placing a container in the woods, noting the coordinates, and then allowing others to locate it using the coordinates and a GPS receiver. The idea took off, and almost 20 years later, the geocaching community has grown almost inconceivably: As of 2017, a whopping 3 million active geocaches are hidden across the globe, just waiting to be found.

There are a lot of different types of geocaches now, but the “original” type is a box or container with a logbook and maybe a few items inside. Once you find one, you write your name in the logbook, and if you feel like it, you can trade one of the items inside for something else you’ve brought along yourself. “Mystery” or “puzzle” caches require geocachers to solve a puzzle in order to find the coordinates to the cache; multi-caches involve a sort of chain of caches, with the first cache containing a clue leading to the second, and so on; and EarthCaches do away with the box entirely, consisting of “a special geological location people can visit to learn about a unique feature of the Earth,” according to Geocaching.com. There are even letterbox hybrid geocaches which hearken back to the days of clues and stamps.

You can see how the line from these real-life activities connects to “Internet Story,” yes? But here’s the thing: Armchair treasure hunts and geocaching don’t just provide the framework for the film. They also provide the tragedy of it, albeit in a slightly different form. The sad fact of the matter is that people have actually died on the search for armchair treasure hunt prizes and geocaches.

For example, the hunt for Fenn Treasure — the chest full of valuables assembled by Forrest Fenn, the clues to which can be found in a poem Fenn published in his book The Thrill Of The Chase — has resulted in four fatalities since it began in 2010: Randy Bilyeu, who went missing in 2016, only for his skeletal remains to be discovered along the Rio Grande a year later; Jeff Murphy, who was found dead on June 9, 2017 after having fallen about 500 feet in Yellowstone National Park; Paris Wallace, who also died in June of 2017 and was recovered downstream of the Taos Junction Bridge in New Mexico; and Eric Ashby, who fell off a raft in the Arkansas River in June 2017 and was found downstream a month later.

And as for geocaching, a bookmark list on Geocaching.com — one of the foremost geocaching resources online today — logs 14 instances of people dying while geocaching. Some had heart attacks; others fell or suffered other accidents; and in some cases, it’s not totally clear what happened. It’s not a complete list, but 14 is still not an insubstantial amount.

Nor, for that matter, is it out of the question for geocaches to be located — usually unintentionally, although not always — in places where dead bodies have been found: Another bookmark list logs 57 records of these kinds of incidents, many of which don’t appear to have been accidents. Consider, for example, the September 2010 incident in which a woman’s dismembered remains were found in a series of concrete containers near a cache in the Waitakere Ranges in Auckland, New Zealand. Or consider the fact that the remains of a man who had been murdered in a drug deal gone bad in 2003 were found near Pyramid Lake, Nevada in 2007 — not too far away from a geocache that had been set up in 2006.

From all of this — and much, much, more — it’s easy to see how something like “Internet Story” could happen in real life. However, to focus solely on the scavenge hunt aspect of the film would be a mistake; after all, as Adam Butcher himself noted, the story is also about “the sometimes faceless, heart-breaking loneliness of the internet” and “the sense of people talking but not connecting.”

Gone Fishing

There’s also catfishing — because ultimately, Al1’s Nine Grand Quest isn’t really an armchair treasure hunt. It looks like one; indeed, it uses the form quite successfully. But what it really is… isn’t that. It’s a catfish story with a terrible ending.

The term “catfishing” has actually been around for at least a century, but it was really the 2010 documentary Catfish and the followup television program that cemented its meaning in our cultural dictionary: It describes the act of creating a false identity and using it to pull a fast one on someone else. The motivations of a catfish might vary widely, which is one of the things that makes the phenomenon so interesting; they might have something nefarious in mind, or they might just be trying to deal with some personal issues and going about it in a less-than-constructive way.

Like the term itself, catfishing has also been around much longer than most people usually think; scammers have been conning marks for centuries, if not millennia. However, the internet has made it easier to catfish someone else than ever; the fact that Catfish: The TV Show has been on the air for seven seasons is a testament to that fact (and while we’re on the subject, who could forget Manti T’eo’s tale of catfishing woe?). That was even the case in 2005, when the events of “Internet Story” are meant to have taken place, and in 2009, when the film was made. It’s true that Al1 didn’t exactly pretend to be someone other than who he was; however, he did pretend that his Nine Grand Quest was for a different purpose than it really was.

The point of the puzzle was never the money.

The point of the puzzle was companionship.

Most of the catfishing stories we hear about — especially the ones on Catfish: The TV Show — don’t result in death; heck, sometimes they even have happy endings. But, like armchair treasure hunts and geocaching, catfishing, too, can be much more tragic than at first it seems.

Consider, for example, some of the most notorious pre-internet catfish: Herman Webster Mudgett pretended to be Dr. H. H. Holmes, wooed women, convinced them he loved them, and killed them both for their money and for the fun of it. Belle Gunness attracted husbands via the personal ads in various newspapers and, like Holmes, killed them for their money. Raymond Martinez Fernandez and Martha Jule Beck, romantically involved but posing as brother and sister, lured in single women with “lonely hearts” ads and killed them.

Obviously not all catfish are serial killers, but… well, you can see a pattern emerge from these particular catfish (and others like them) pretty clearly. It has continued in the digital age, too; you only have to look at Philip Markoff, the “Craigslist killer,” who preyed on sex workers advertising in the adult services section of Craigslist, to see that.

And, worse, there are stories like Megan Meier’s. In 2006, a fabricated account purportedly belonging to a 16-year-old boy called “Josh Evans” had been created to cyberbully Meier; after “Josh” sent her a series of cruel messages, she died by suicide. She was 13 years old.

Any number of situations could have occurred in “Internet Story” — many of which have occurred in some form in real life before. Maybe Al1 meant to lure someone in with the Nine Grand Quest expressly in order to kill theme. Maybe he lured them in intending to befriend them or romance them, only to have the final meeting go awry — Fortress rebuffed him, leading Al1 to kill him in retaliation, or Al1’s intentions affronted Fortress, leading the seeker to kill the puzzle master instead.

Or maybe there was an accident of some kind.

Or maybe something else happened entirely.

All of these possibilities are equally likely.

This Is A True Story About The Internet

Ultimately, what I’m getting at is this: The reason “Internet Story” is so freaky is because it’s a story we know. The different elements at play in the film? We’ve seen them all in real life before. We may not have seen them assembled together in quite the same way — I was unable, for example, to dig up any real-life news stories centering around killers using geocaches to lure in victims — but we know them all: We know armchair treasure hunts and geocaching. We know lonely hearts killers and catfishing and cyberbullying. It really is “a side of the internet that we’ve all… experienced.”

The film even tells us that this is what we can expect from it right from the get go. Consider the opening narration again: “This is a true story about the internet,” it begins. But then, it continues, “Please, don’t go” — as if it’s afraid that we won’t find it interesting enough to stick with it. But it’s got something up its sleeve it thinks you’ll like: “It’s also the story of a treasure map, and a murder,” it says, “and it’s a story that I stumbled upon, just like anyone else might.”

And then, finally: “Let me show you.”

It’s that attempt to reach out, hoping that someone will meet you at the other end, but not knowing who or what you might find when you actually get there.

And what could be more familiar — and more terrifying — than that?

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via AdamButcher/YouTube (3); Amazon; screenshot/Al1’s Nine Grand Quest (2); Lucia Peters/The Ghost In My Machine; Wikimedia Commons; chrisci/Pixabay]