Previously: The Sallie House.

It’s a fixture of the landscape: 45 feet high and 350 long, stark white against the surrounding brush of Mount Lee, yet harmonious with the blue of the sky above it. It imparts one message, but also many — so much conveyed in just one word: “Hollywood.”

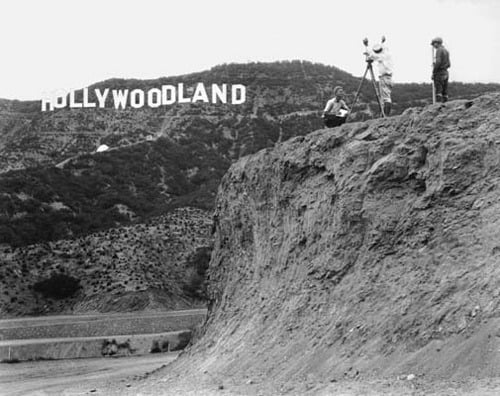

Of course, the Hollywood sign wasn’t always the Hollywood sign; it’s fairly common knowledge by now that originally, it was the Hollywoodland sign. It also wasn’t necessarily meant to stand the time in quite the way it has: It was, after all, originally just an advertisement for a real estate development. But it has become iconic — if there’s one thing people think of when they think of L.A., it’s the Hollywood sign — and, as is often the case with iconic places and things, it’s also gotten a reputation for being haunted. Given Hollywood’s long, storied, and often seedy history, it’s not surprising that its most notable landmark might have this sort of reputation — but if you had to pinpoint where it all began, it always comes back to one person: Peg Entwistle.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

In the early 1920s, the American motion picture industry was still somewhat fledgling, although it was steadily on the rise. Filmmaking companies had begun to set up shop in Southern California roughly a decade prior, seeking to escape the jurisdiction of Thomas Edison’s Motion Picture Patents Company in New Jersey; they flocked to Los Angeles, particularly the area known as Hollywood, formerly a municipality which had merged with L.A. in 1910. Interest in the movie industry had prompted the building of a real estate development in Hollywood meant to capitalize on the cinema’s glitzy image. This was Hollywoodland.

The sign may never have happened had Los Angeles Times publisher Harry Chandler not decided to invest in the Hollywoodland development in 1923. $21,000 from Chandler and his partners went towards the sign, which was illuminated with 4,000 bulbs. It flashed in four parts: First “Holly,” then “Wood,” then “Land,” and finally the entire word. It was only meant to stay up a year and a half — but by the time came for the sign to come down, it had become too recognizable for anyone to want to do away with it. The sign stayed.

In contrast, by the time Peg Entwistle arrived in Hollywood in the early ‘30s, the Golden Age of Hollywood was well underway. The release of The Jazz Singer — the first talking picture — in 1927 had marked its beginning, and the studio system, controlled by the Big Five of MGM, Paramount, RKO, Warner Bros., and 20th Century Fox, would reign supreme for the years to come.

Peg wasn’t her given name, by the way; when she was born in Wales on Feb. 5, 1908, her parents named her Millicent Lillian Entwistle. She came from a theatrical family: Her father, Robert, was an actor and occasional set designer, and her uncle, Charles — somewhat more successful than Robert — was a manager and actor. Her mother, Emily, is often reported to have died when Peg was young, but that’s actually not the case — records show that Robert divorced her when Peg was two for reasons unknown. Robert gained sole custody of Peg; she spent her early years in London before she and her father emigrated to the United States sometime around 1913. Though sometimes referred to as “Babs,” particularly as a young girl, the name “Peg” came to her later on, through the play Peg O’ My Heart.

I won’t go into a blow-by-blow account of Peg’s family history and her early life — for that, I’ll recommend you check out James Zeruk Jr.’s excellent Peg Entwistle and the Hollywood Sign Suicide, recently brought to my attention by the podcast You Must Remember This. But suffice to say that Peg eventually — perhaps inevitably — made her way to the stage; indeed, in an oft-cited anecdote, her performance as Hedvig in Ibsen’s The Wild Duck at the end of 1925 inspired Bette Davis to pursue her dreams of a life in show business. Her first professional role actually happened a few months earlier, a walk-on role in Hamlet on Broadway; she then appeared in The Rivals, Rip Van Winkle, the aforementioned production of The Wild Duck, and Enter Madame at the Repertory Theatre of Boston. More roles throughout the rest of the ‘20s and the early ‘30s followed, including a number of Broadway credits; she was also briefly married to actor Robert Keith from 1927 to 1929, although she divorced him quickly on the grounds of cruelty and deception. More or less in tandem with the divorce, Peg moved to Los Angeles.

It’s tempting to say that that’s where it started to go wrong, but as is often the case, that’s only part of the picture. Although Peg had been to L.A. before — pieces of her show biz family had made their home there — she had never intended to make Hollywood her goal, preferring the stage to the screen. But her tumultuous relationship with Keith had left its mark: Constantly needing to bail him out of jail for everything from drunkenness to late alimony payments (for a child from a first marriage Peg had no idea about until after she had married Keith) had left Peg in dire financial straits, and the drama caused by the relationship itself while performing on tour with Keith had resulted in her being more or less blacklisted from the prestigious touring company (which she had hoped to continue working with). She wasn’t in good shape, and when she settled in Los Angeles after the tour wrapped up, she was showing signs of depression. It likely wasn’t the move itself, but everything that had led up to it that signaled the forthcoming tragedy.

A struggling Peg eventually landed a role in the film Thirteen Women, produced by RKO, only to have most of her scenes end up on the cutting room floor. Afterwards, she was nearly broke and unable to find more work; she lacked the money even to leave Los Angeles and return to New York.

We don’t know a lot about what prompted her next decision, and honestly, I don’t think it’s helpful to speculate. What we do know, though, is this: On Sept. 16, 1932, Peg wrote a note, put it in her purse, hiked up Mount Lee to the Hollywood sign, and climbed to the top of the letter H using a ladder for assistance. Then, she jumped.

She was found by a hiker on Sept. 18, deceased at the age of 24 years old. The note she had written read, “I am afraid I am a coward. I am sorry for everything. If I had done this a long time ago it would have saved a lot of pain. P.E.”

The ghost stories started a few years later, perhaps spurred on by the collapse of the H in the 1940s — the letter Peg had climbed that last night of her life. The sign had begun to fall into disrepair, and after the H toppled away, the city of Los Angeles almost scrapped the sign completely. However, a deal was struck instead: The Hollywood Chamber of Commerce would restore the H in exchange for the removal of the L, A, N, and D. (Contrary to popular belief, the last four letters were not, in fact, the victims of a landslide.)

Thus, the Hollywoodland sign became the Hollywood sign.

According to the stories, a blonde woman — pretty, sad, and wearing clothing similar to the styles worn in the ‘30s — will sometimes appear on the paths of Griffith Park on foggy nights. The scent of gardenia accompanies her, but should you approach, she’ll vanish. She’s reportedly been seen by everyone from park rangers to visitors who have no idea who Peg Entwistle is. She doesn’t always walk directly on the path; speaking to Vanity Fair in 2014, Megan Santos reported that the mysterious blonde figure “seemed to be, like… walking on air.” Animals, too, are apparently sensitive to her presence: Reportedly, a couple walking their dog along one of the park’s trails noticed their pup beginning to whimper and behave oddly shortly before they spotted a woman appear in front of them — a woman who then vanished as quickly as she appeared.

Sometimes I wonder what it is about Hollywood history that lends itself so strongly to stories cloaked in darkness. I suspect, though, that it has something to do with the disconnect between the image presented by Hollywood and the reality of it all. When we think “Hollywood,” we think glitz and glamour; deep down, though, we know that it’s not real — that it’s paint and clever lighting, flats, not real landscapes. Particularly during the Golden Age, the goal of movies produced in the Hollywood system was to help audiences escape from the reality they lived every day: One of the most devastating wars the world has ever seen. We might smile and sing and put on a happy face, but it’s mostly to distract ourselves from what’s lurking underneath it all. As the saying goes, we laugh, because we’ll cry if we don’t.

That knowledge, I think, is what spurs our interest in these stories. We know the image of Hollywood is too good to be true. So, we seek out its underbelly, trying to prove to ourselves that we are not fooled — that we know the truth.

But I’m not sure we’re actually succeeding in that goal. Our tendency is to take these tragic histories… and then turn them into ghost stories, building yet another level of unreality into the whole thing. I can’t help but think that these layers upon layers of stories ultimately obscure things even further. We’re not really getting to the bottom of it; we’re just telling ourselves another fiction.

There’s one last chilling detail to Peg’s story, though. The day before Peg made her fatal climb, a letter had been put in the mail for her. It was from the Beverly Hills Playhouse, offering her a role. The letter was delivered the day following her death; if she had received it, it would have put an end to her working dry spell.

The mere fact of the letter is tragic and ironic enough on its own — but it’s the role itself that really clinches it: The character was a young women who, in the final act, dies by suicide.

Resources:

Peg Entwistle and the Hollywood Sign Suicide.

You Must Remember This, episode 93: “Peg Entwistle (Dead Blondes, Part 1).”

Is The Hollywood Sign Haunted?

The Woman Who Jumped Off The Hollywood Sign.

The Hollywood Sign Originally Read “HOLLYWOODLAND.”

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!