Previously: The Decatur Waterworks, Georgia.

In Rockland County, New York, a little more than 50 miles north of New York City, lies Bear Mountain State Park. Situated along the west bank of the Hudson River, Bear Mountain has all the activities you’d expect from a good state park: Fishing, swimming, cross-country ski trails, picnic spots, and, of course, hiking. Along those hiking trails, however, you can also find something that’s a little less common in state parks: The ruins of a small town — not even a town, really; a hamlet, officially — once called Doodletown.

It’s not habitable now; nothing but foundations, staircases, and a few cemeteries remain. No one has lived there since 1965. But before then, Doodletown had a long, long life — one that’s still buried beneath the greenery, for those who would care to look.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

Although the name “Doodletown” might imply some sort of graffiti park or art installation, that’s actually not the case. It’s also, however, not totally clear from whence the term did in fact come.

For what it’s worth, it’s sometimes — often, in fact — said that the name “Doodletown” is derived from “doddel” or “dooddel,” which are both usually identified in this context as Dutch words that translate to “dead valley.” However, I haven’t found any sources with credible citations for this factoid — nor even any Dutch-English dictionaries that contain translations for “doddel” or “dooddel.” At most, I’ve seen it repeated without citation, so it’s possible that this supposed etymology is apocryphal, or a folk etymology.

That said, “dood” is the Dutch word meaning “dead,” so there still might be something to it. (I can’t account for the “-el” portion of “doddel” or “dooddel,” however; from what I can tell, the Dutch word meaning “valley” is “vallei.” I’ve occasionally seen “tal” pointed to as the origin of the second half of the word, but similarly, I haven’t been able to find an actual Dutch-to-English dictionary entry for “tal,” so I can’t really say what it means one way or the other.)

In any event, Doodletown has a long history — one that goes back many thousands of years. And what all of those years have in common — what contributed to and ultimately caused Doodletown’s eventual abandonment — is land acquisition: It was repeatedly sought after and sold, over and over again, often without regard for what those who actually lived there wanted.

Like much of what’s now called the Lower Hudson Valley, the area that contains Doodletown is Lenape land; its indigenous inhabitants were the Munsee. But in 1683, this land was sold to Stephanus van Courtlandt as part of a purchase totaling 1,500 acres in and around what’s now referred to as Anthony’s Nose.

By the mid-18th century, a family named Tomkins was living in the area — and in 1762, the Tomkins family sold a number of acres to Ithiel June, Jr. and his spouse, Charity. These acres would, over time, become Doodletown, with the June family and its descendants as the primary force behind the development of the community. By 1780, the actual placename of Doodletown had even made its ways onto maps of the area.

Gradually, over the years, decades, and centuries, developments in the area led to the establishment of many of Doodletown’s primary landmarks. For instance:

During the Revolutionary War, trails were created by British troops to attack American forts; these trails remain today, and are (usually, though not presently — more on that in a bit) hike-able within the Palisades Interstate Parks system.

By the mid-1850s, John Beveridge had purchased what was then called Salisbury Island, and which is now Iona Island. Over the course of its history, Iona Island would serve a variety of purposes, from housing Doodletown’s church, to providing a recreation spot as an amusement park and picnic grove, to being the base for a naval ammunitions depot. Today, it’s a bird sanctuary; bald eagles often nest there during the winter months.

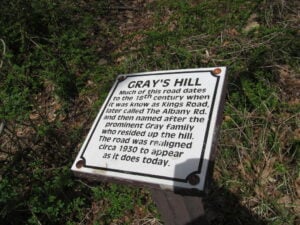

Sometime around 1900, the Gray family bought a sizeable chunk of land and built a mansion on it. That piece of land is now called Gray’s Hill. And nearby, construction on the Bear Mountain Inn was completed not too much later, in 1915; the inn is still operational today.

But when we talk about Doodletown’s abandonment, and the remains of the town which can still be found if you look closely enough, what we mostly mean is Doodletown as it was in the 1950s — its last iteration, if you will.

Doodletown was never a large community; at its peak in the 1940s, it had a population of around 300 — maybe 350 at the outside — filling around 70 houses and residences. But it still had its own church, and a school, and several cemeteries, and even though residents did have to venture outside the town for things like shopping or work, it was, according to those who lived there, thriving, despite its small and somewhat isolated nature.

Its days as a place to live, however, were numbered. Throughout the 1950s, Doodletown was in decline, with financing for homes drying up as the area fell more and more under the purview of the Palisades Interstate Parks system.

The Palisades Interstate Parks Commission formed at the turn of the 20th century as a means of combatting threats to the natural beauty of the area — things like quarrying along the Hudson River, a proposed plan for a prison to be built on Bear Mountain, and so on. The idea was to preserve the New Jersey Palisades and the Hudson Highlands and make them visitor-friendly. Bear Mountain became what Elizabeth Salter termed the “nucleus” for the park in her indispensable 1996 book Doodletown: Hiking Through History In A Vanished Hamlet On The Hudson, and as the years went on, more and more previously lived-upon land went to the park.

By the late 1950s, it had become clear that it was only a matter of time before the area had transitioned entirely into park land, rather than livable land — hence the refusal of lenders to offer financing for those who still hoped to move to or build housing in Doodletown. Residents eventually began to move out, one by one, with the final few leaving in 1965.

The remaining buildings and structures were subsequently demolished to make way for a winter sports recreation center — although that particular project never came to fruition. Doodletown was razed, and then left to its own devices.

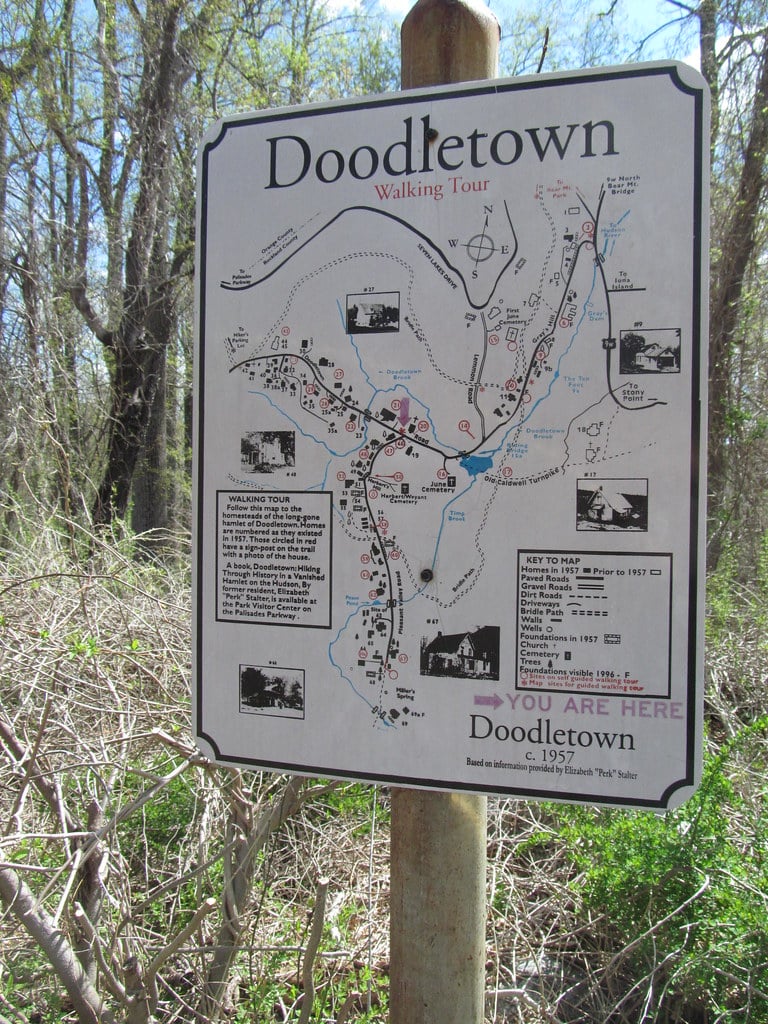

But even though the town is no longer a town, traces of the town remain — and, indeed, can even be visited, under the right circumstances. Doodletown’s former location was incorporated into the hiking trails that run through Bear Mountain State Park; following the 177E trail — which has, as its backbone, the previously-mentioned trails forged during the Revolutionary War — will take you to Doodletown Road, allowing you explore what remains of the former hamlet.

There, you’ll find foundations, staircases, and other remnants of Doodletown, many with signs detailing what used to be there. Highlights include the first and second June family cemeteries — the first having been in operation from 1762 to 1842 and the second from 1871 to the present — along with the second schoolhouse, in operation in its original function from 1887 to 1926, after which it became a community center; the second church, in operation from 1889 until the closing of the town in 1965; and numerous homes, including many belonging to members of the June family, as well as the house in which Doodletown: Hiking Through History In A Vanished Hamlet On The Hudson author Elizabeth Salter lived from 1950 to 1959.

The suggested hiking route is a loop totaling about 3.8 miles, although it’s of course longer if you choose to roam around Doodletown while you’re at it.

Unfortunately, though, if you want to make that hike, you’re going to have to wait. Doodletown has been inaccessible since the summer 2023; an extreme storm event in July of that year damaged huge swathes of Bear Mountain and Harriman State Parks, including the area where Doodletown’s remains are located. It’s still not fully open yet, and there doesn’t seem to be much of a timeline on when or even if it will have been restored enough to use.

Hopefully the last remnants of Doodletown will survive. But even if they do not, those who lived there — those who grew up there — still remember, and still tell the stories of what it was like in this small, tiny hamlet in the woods on Bear Mountain.

And as long as we have those stories, a place can never truly die.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Bluesky @GhostMachine13.bsky.social, Twitter @GhostMachine13, and Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And for more games, don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos available under CC BY 2.0 DEED and CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED Creative Commons licenses; see individual photos for specific credits.]

Leave a Reply