Previously: Yotteno Wants To Call You.

Decades ago in the UK, there were rumors about what might happen if you went to a public phone box and dialed a specific phone number. The rumors didn’t always agree on what the number itself was (although often, it’s remembered as 20202020)— but what they did agree on, mostly, was what you’d hear on the other end, echoing back at you down the line: A woman’s strangely monotone voice saying, repeatedly, “Help me. Help me. Susie’s dying.” Over and over, as if it were a recording playing back at you: “Help me. Help me. Susie’s dying.”

But what’s the truth of the story? Did the Susie’s Dying phone number and message actually exist? And if so, what were they, really?

It’s a mystery that’s spanned decades, and even now, it still inspires speculation. Heck, I’ve even covered it myself here at TGIMM twice in the past — once in 2016 for our long-running Encyclopaedia Of The Impossible feature, and again briefly in 2021 as part of a larger roundup of scary stories and urban legends based around allegedly “haunted” phone numbers.

The interesting thing about this story is that there is… no new information available. Not really. What you see is what you get with this one — although, as it turns out, there’s more to be found with what we already have if you examine it closely.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

For that reason, I think it’s worth taking another look at the Susie’s Dying phone number story—a closer one that builds out the bigger picture a bit. Because even though we still don’t really know what the real story was — and, in all probability, we never will — there’s enough out there that we can make a few educated guesses about it all.

Ready?

Here we go.

The Haunted Phone Box: A Legend Begins

There are four primary accounts of the Susie’s Dying legend that are passed around so frequently, they’ve more or less become pieces of copypasta. They’ve been posted to a not-insubstantial number of online forums and message boards over the years, including Reddit and 4chan, and pretty much always in the same format: A short paragraph describing a memory, followed by the name of the person in possession of the memory, where they live, and the year they wrote the recollection down.

The first of the accounts, though, is probably the most notable, largely because it’s the least garbled and contains the most information. Dated 2000 and written by a Rob Dickinson located in Worsthorne, Lancashire, it reads as follows:

“Back around 1975 when I was nine, some of the kids I knocked around with insisted we all pile into the nearest phone box to hear a spooky message. By dialing a number — I think it was made up of zeros, twos and ones — and without needing to insert two pence, a woman, speaking in a curiously monotone voice, could be heard saying ‘Help me, help me, Susie’s dying’ over and over. Some of the lads said she sometimes said ‘Help me, help me Susie’s drowning’ — always in the same slow, seemingly bored tone of voice. Was it some weird engineer’s test signal (hence no money needed)?”

The other three accounts, which were all recorded circa 2000-2003 and recount events that took place either in the 1970s or in the early 1980s, built off of this one, adding more details as the conversation continued on. Between these four stories, we get the following information:

- That the phone boxes used to make the calls were located in villages in and around the UK town of Burnley, up north in Lancashire;

- A few possible phone numbers that were dialed to access the message, described variously as a combination of zeros, twos, and ones; a combination of threes and twos; and the number 20202020;

- A timeframe during which this strange phone message existed (1970s – 1980s);

- And, of course, the message and its delivery: “Help me. Help me. Susie’s dying,” spoken by an emotionless, female-sounding voice and seemingly playing on a loop.

Upon further examination, it becomes evident fairly quickly that these four accounts are not only the primary accounts typically pointed to as evidence of the Susie’s Dying phone number’s existence, but also very close to the only accounts. (They’re not the only accounts, but others are very few and very far between. We’ll get to that in a bit; all in due time.) Furthermore, there’s very, very little information about the Susie’s Dying phone number available from sources outside these four accounts — that is, basically everything we know about it comes entirely from people’s memories. And, as Leonard Shelby once told us, memory is unreliable.

To get at what might be something resembling the truth of the story, we have to start by tracing those memories. And that trail both begins and, more or less, ends in the same place: The Fortean Times.

It Happened To Me! Or, True Stories From The Fortean Times

Founded in 1973 and named for noted researcher and writer Charles Fort, the Fortean Times is a magazine that specializes in reports of the odd, the mysterious, and the unexplained — topics that might be referred to as paranormal, or otherwise classified as anomalous phenomena or high strangeness.

Originally produced independently as The News by Bob Rickard before gaining its current title in 1976 with issue #16, the magazine has had a number of publishers over the years. In 1991, it fell under the publishing umbrella of John Brown, followed by a stint with I Feel Good in 2001 after IFG’s acquisition of many of John Brown’s consumer titles. Then, in 2005, Dennis Publishing acquired IFG, gaining the Fortean Times as it did so. Dennis Publishing was itself then acquired in 2021 by private equity firm Exponent, which quickly turned around and sold a number of Dennis titles to Metropolis International. These days, the Fortean Times is published by Metropolis’ consumer arm, Diamond Publishing.

Like many magazines, the Fortean Times has long had a practice of publishing letters submitted by readers in addition to its regular articles and journalistic features. These letters frequently describe strange events their writers experienced firsthand; as such, they’re typically compiled in a section bearing the title, “It Happened To Me!” (The section is so popular that it spawned a board on the Fortean Times‘ Forteana forums with the same title; it, too, is dedicated to real, reader-submitted stories.)

And the four most frequently cited Susie’s Dying stories? Those were originally letters published in the “It Happened To Me!” section of the Fortean Times.

I haven’t been able to determine the precise issues in which the latter three letters appeared, but the first one, Rob Dickinson’s, was in either the October or September 2000 issue — issue #138 or #139.

Unfortunately I’m uncertain as to which, as I haven’t been able to get a hold of either issue to check myself — they’re old enough that haven’t been digitized (I’ve only found digitized issues dating back to 2012), and I don’t currently have access to hard copies of them.

For what it’s worth, though, I suspect it might be the October issue. A newsgroup discussion about the phone number which began on Oct. 7, 2000 — right around the time when the Dickinson letter was first published — cites the October issue of that year as the source, minus the actual issue number. A later post on the Forteana forums from November of 2020 does refer to it as “Issue 138 (October),” but as issue #138 seems to have actually been the September 2000 issue, I’m not totally sure who’s correct here.

(Concerning the discrepancy: The cover of the September 2000 issue can be seen here bearing the issue number of 138, while this timeline of FT covers published by the Guardian back in 2013 shows August 2000 as being issue #137. Just, y’know, citing my sources here.)

In any event, that letter from the fall of 2000 kicked off the small chain of recollections that would follow for the next few years, with at least three more letters being submitted to the “It Happened To Me!” section of the magazine.

And, as it turns out, there’s also a reason these four accounts are so often lumped together, despite the fact that they bear different dates: They appeared as a group in one of FT’s spinoff projects.

In the late 2000s and early 2010s, when it was still under the publication umbrella of Dennis Publishing, the Fortean Times put out six books — or “bookazines,” as I’ve sometimes seen them called — assembling collections of “It Happened To Me!” letters originally submitted to the magazine and publishing them in standalone volumes. Also titled It Happened To Me! and featuring the subtitle “Ordinary people’s extraordinary true stories from the pages of Fortean Times,” the books in this series came out roughly once a year starting around 2008 or 2010. (Again, there’s some confusion here; I’ve seen both dates on actual copies of the first book, so I suspect that the hard copies might have started publishing in 2008, with digitized versions coming along in 2010.)

The four Susie’s Dying stories all appear in the very first volume — something I can confirm without a doubt this time, as my local library turned out to have the first three It Happened To Me! books available in its digital collection. (Yes, I checked them all out, and yes, I read all of them. Libraries are great! Support your local libraries!) The Susie’s Dying letters are filed under Chapter 9: Down The Line, as part of a collection of about a dozen total letters centered around telephone-related oddities.

So: That’s where the core four Susie’s Dying stories come from. But are there any others? And if there are, can they supply more information about the phone number itself?

Further Exploration: Other Accounts And Recollections

The FT letters may be the accounts that are passed around most frequently — but, to answer the question I just posed, yes, there are a few others scattered across the internet. There aren’t many, but there are a few. And that, as they say, isn’t nothing.

The newsgroup thread I mentioned further up — the one started in 2000 shortly after the publication of the Dickinson letter — contains an account posted in 2015 (yes, a full decade and a half after the thread kicked off) which describes an experience with the phone number:

“I can absolutely confirm that this actually happened! This is how it worked. You’d dial a few numbers by tapping the receiver holder, not dialing the number via the dial. This is due to the signal being analogue and numbers were literally tones. You’ve then heard a male voice say ‘start test,’ which would repeat until you put the receiver down. The phone then rings and depending on the test you’d hear either tones or messages. The Susie message was the only one I could remember and it actually said it in a low, female, stern voice: ‘Susie’s dying, help me’ and repeat. The voice DIDN’T say ‘help me, help me, Susie’s dying.’”

The account continued:

“This was in a phone box around 1979 in a village called Fence near Burnley. Strangely enough there are other stories like this that are from people in Burnley. I can hand on heart remember this clearly, so all I’ve stated is fact and not blurred memories!”

This poster’s experience lines up with much of what the previous letters described: A timeframe between the 1970s and 1980s; a phone box in a village near Burnley; and a female voice repeating a message about someone named Susie dying and asking for help. This poster also corroborated something posited by Rob Dickinson in his original FT letter: That the message was part of a test system.

The new information here, of course, is how the number was actually dialed: Via taping on the receiver, rather than using the dial. We’ll come back to that in a little bit, but just… keep it in mind for now.

It should be noted, by the way, that another account in this newsgroup thread recounting an allegedly recent experience with the phone number — one dated 2018 and written by a YouTube going by the name MrDachshund99, who also published a corresponding video supposedly “documenting” the experience on his channel — was later debunked. Another YouTuber exploring the Susie’s Dying legend, Shrouded Hand, got in touch with MrDachshund99 as part of the process of putting his own video together in 2019 — and MrDachchund99 confirmed that it was just a short film he had made for fun. MrDachshund99’s video allegedly documenting the call — which, again, was a straight-up fabrication — has since been removed or otherwise hidden from his channel.

However, the Shrouded Hand video about the Susie’s Dying number is also worth paying attention to for another reason beyond the debunking: A viewer writing in the comments detailed their own experience with the number when they were young. Wrote YouTube user midnightmosesuk:

“I tried this with a friend during the ‘70s. I lived in Thamesmead at the time. It must’ve been around ‘75 or ‘76. There was a phone box not far from where I lived and we cycled over to try out this rumour. I guess you can guess what happened next, we rang the number and got the ‘help me, Suzie’s [sic] dying’ message. We jumped on our bikes and cycled for dear life. … What scared me wasn’t the message itself so much as the feeling that I’d done something that felt forbidden and wrong. There was a real sense of a line being crossed, if you’ll forgive the pun.”

In a follow-up comment, midnightmosesuk described using the tapping method also used by the writer of the 2015 newsgroup post: “It had to be tapped out on the phone cradle, so my memory of the number is sketchy; it did contain 010, though. I remember that because to get to 0, you had to tap the cradle 10 times, so going from 0 to 1 then to 0 again made it easy to make a mistake.” (They did also state that they weren’t the one who actually tapped out the number; a friend they were with did, so do with that what you will.)

Again, we have the timeframe (the 1970s); the number (something involving zeroes and ones); the tapping method; and the message itself, which midnightmosesuk described as being a monotone woman’s voice that sounded “like a looped tape recording,” rather than someone speaking live. We do, however, have quite a departure in location here: Thamesmead is a part of London, and is, therefore, much further south than Burnley — roughly 420 kilometers, or about 265 miles, a distance that’s at least a four-and-a-half-hour drive.

But what are we to do with this new information? Was the Susie’s Dying number really a test of some sort, as both the Rob Dickinson letter and the 2015 newsgroup post suggest? What about the inconsistencies in how the number was actually called — whether dialing or tapping the receiver?

For all of that to start making sense, we have to talk a little about how telephones worked in the UK at that time — and, in particular, how public phone boxes worked.

Stay with me, now.

You Know My Name, Look Up The Number: A Brief Look At British Telecoms

First, a little history, just for context:

Prior to 1969, British telecoms were part of a government department called the General Post Office, or GPO. Thanks to the Post Office Act of 1969, however, the GPO became simply the Post Office, which was no longer a department of state, but a public corporation. Two divisions were set up under the Post Office umbrella: One which continued to handle the actual mail, and another — Post Office Telecommunications — which handled the telephone network.

In the early ‘80s, however, things changed again. Post Office Telecommunications was separated out from the Post Office and became British Telecom (BT), with the telephone network transferring away from the Post Office and over to BT with the British Telecommunications Act of 1981. In 1982, BT’s telephone monopoly was broken by the arrival of the now-defunct telephone company Mercury Communications, and shortly thereafter, BT began privatizing.

During the period of time all this was happening — that is, from 1969 through the early 1980s — the telephone network as a whole saw massive modernization and development, with both subscriber trunk dialing (which didn’t require calls to go through an operator at a switchboard in order to be made) and international dialing (call the rest of Europe! Call the United States! Call Canada! Call everywhere!) picking up steam, along with digital exchanges being installed as well.

It’s also, interestingly, the period of time during which all of the Susie’s Dying phone number stories reportedly occurred: The accounts pick up shortly after the changes brought out by the Post Office Act of 1969 kicked in and faded away around the time the telecoms industry in the UK began privatizing. I don’t know that we should make too much out of this particular connection — but I do think it’s usually worth paying attention when particular stories or urban legends proliferate around times of change or upheaval. They often function as ways to cope with uncertainty or doubt in the face of the unknown — even if “the unknown” in this case is just changing telephone technologies.

In any event, knowing this context, I wanted to see what I could find out about testing procedures for public phone boxes during this period. The frequently-brought-up proposal that the Susie’s Dying message could have been part of a test of the phone system seemed not unreasonable — and, as it turns out, there’s a website out there that goes into exhaustive detail about the British telephone system pre-1990 that does, in fact, have some relevant information. Called, appropriately, BritishTelephones.com, it’s not an easily navigable site —but if you manage to find your way to the right page, there’s a wealth of primary documents available as PDFs detailing engineering instructions for the installation and maintenance of CCB, or coin collecting box, phones — that is, the kind of telephone you’ll find in public phone boxes.

There’s one specific document I want to look at here — one discussing testing procedures to be carried out by engineers make sure the phones and their coin collecting boxes are functioning properly. The document is dated 1961, so it’s a little earlier than most of the Susie’s Dying stories (and alas, this 1961 document is the latest one I could find, hence why we’re looking at it and not at a document from, say, 1975) — but there are a number of details in it that seem to corroborate a few of the details from the accounts we have of the Susie’s Dying number.

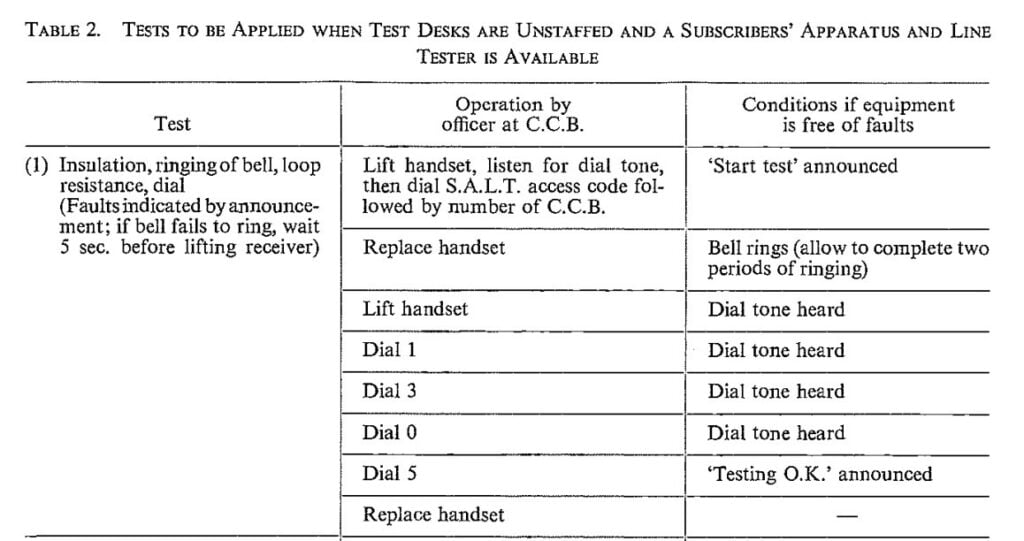

The document is divided into a couple of different parts: “Tests To Be Applied When Testing Facilities With A Test Desk Are Available,” “Tests To Be Applied When Test Desks Are Unstaffed And A Subscribers’ Apparatus And Line Tester Is Available,” and “Tests To Be Applied When Testing Facilities With A Test Desk Or A Subscribers’ Apparatus And Line Tester Are Not Available.”

The first section isn’t what interests me here; the tests performed when testing facilities and a test desk are available means a live person picks up on the other end when you’re performing your tests, and it’s pretty clear that the “Susie’s Dying” message is a recording of some sort. Nor is the third, which just… doesn’t really have anything we need in it.

So, we go to section two: Tests performed when you don’t have a staffed test desk available. And, lo and behold, the very first test listed under this section — a test for “insultation, ringing of bell, loop resistance, [and] dial” wherein “faults [are] indicated by announcement” — contains some incredibly familiar-looking info.

In the column describing the actions the engineer should take within the phone box in order to perform the test — the column headed with “Operation by officer at C.C.B” — we have, “Lift handset, listen for dial tone, then dial S.A.L.T. access code followed by number of C.C.B.” (The acronym S.A.L.T. stands for “subscribers automatic line test”; meanwhile, the “number of C.C.B.” just means the number you’d dial to reach this particular phone box.) And then, under the next column over, “Conditions if equipment is free of faults” — that is, what the officer can expect to happen if the phone box is in working order — we have, “‘Start test’ announced.”

That’s right — just as the writer of the 2015 newsgroup post said happened when they dialed the Susie’s Dying number.

Further instructions include the officer replacing the handset, waiting for the phone to ring twice, picking up the handset, listening for a dial tone, and then dialing the numbers 1, 3, 0, and 5 for more test tones, followed a “Testing O.K.” announcement.

The sequence of events and resulting sounds in this test are, of course, a little bit different from those detailed in the Susie’s Dying stories — namely, there’s no mention of a recorded message playing at all, let alone one relaying the phrase, “Help me, help me, Susie’s dying” — but again, this document is from 1961. It’s not outside the realm of possibility that between changing times and changing phone box technology that the procedures may have changed a little bit between then and the ‘70s, when most of the Susie’s Dying stories take place. Just, y’know… food for thought.

And what about the actual act of accessing the Susie’s Dying message in the first place? Some accounts stated they simply dialed the number — which is also what the maintenance document guides engineers to do in order to conduct their tests — while others described forgoing the dial and tapping the receiver to make the call. What are we to make of that?

The “tapping the receiver” method does seem to have been a popular way to get around having to pay to make a call at the time; you might know it better as phone phreaking. Because of the differences between the systems, UK methods for phone phreaking were a little different than those used in the United States, but the end results were more or less the same. Here, tapping the receiver mimicked the clicks or tones that usually resulted from using the dial, thereby sending the correct signals to make the call without using the dial itself.

You could do this both with regular phone numbers, and to call phone numbers typically used for testing purposes. But although you could make test calls using the tapping method, you didn’t have to make them that way — so I suspect that the seeming inconsistencies around access in the Susie’s Dying stories are less actual inconsistencies and more just people describing the different methods available of accessing the same number.

So: Where does all of this leave us? Here’s one possibility of what may have actually been going on with the Susie’s Dying phone number:

“Help Me, Help Me, Susie’s Dying”: Towards A Working Theory, And The Questions That Remain

As several accounts suggest, what was basically happening could very well have been regular people accessing a test message not originally intended for public consumption. This test message could be reached by dialing the correct test number — either by using the actual dial or by using the tapping method, both of which could be done without needing to pay — hence the slight discrepancy in how those who recall hearing the message remember actually reaching it. Eventually, the message became unreachable, either due to changing telephone technologies making it harder to access or the message itself being retired. Now, all we have are stories — the memories and recollections of those who recall hearing it.

Of course, there’s still a lot left unexplained. Although most of the stories seem to come from the Burnley area, there’s one outlier — the Thamesmead story. Initially, I’d wondered if the Susie’s Dying message had been specific to Burnley; however, given how far away Thamesmead is from Burnley, we have to consider the possibility that it might have been nationwide, not just regionally available. But if that were the case, then why aren’t there more stories about the Susie’s Dying message from elsewhere in the UK?

And — most importantly, I’d argue — there’s this: If the “Help me, help me, Susie’s dying” message was a test recording, why the heck was something so unsettling not only considered, but actually put into practice?

A post in a thread on the Forteana forums from 2004 discussing the original Rob Dickinson letter drew attention to one possible theory: That the recording was saying not “Help me, Susie’s dying,” but “Hold please, user dialing,” with the poor quality of the recording causing it to be misinterpreted. Without access to the original recording, though, we’ve got no way to confirm whether or not this theory could be the case.

I suppose it’s also possible that the message could have been part of not just a general test, but more specifically some sort of emergency response test. Again, though, I don’t currently have a way to make a ruling on this theory either way, so it remains just that — a theory.

Regardless, what is interesting about this one is that — unlike a number of urban legends about phone numbers — I currently fall on the side of thinking that it did actually exist. But unfortunately, this is where we have to leave it for now — and, I suspect, for good. Documentation is scant; unless something previously undiscovered emerges, all we really have to go on is theories. Furthermore, we are none of us getting younger, and with the heyday of the Susie’s Dying phone number nearly a half-century behind us… well, even those who remember calling it won’t be around forever.

Still, though.

Maybe —

Just maybe —

If you dial the right number —

You, too, might hear a curiously flat voice coming at you down the other end.

Help me.

Help me.

Susie’s dying.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via wenzlerdesigns, 652234, e_klloyd, Alexas_Fotos/Pixabay; screenshot/Google Maps; NotFromUtrecht, Dewi/Wikimedia Commons, available under CC BY-SA 3.0 and CC BY-SA 2.0 Creative Commons licenses]