Previously: A History Of Haunted Attractions In The United States.

Wax museums are fun, but they’re also undeniably creepy. But creepier even than your standard wax facsimiles of Marilyn Monroe, Michael Jordan, and Elton John are wax facsimiles of… well, death. The kinds of waxworks that made one particular area of Madame Tussauds — arguably the most famous wax museum in the world — especially notable: The Chamber Of Horrors.

It’s true that many wax museums have exhibits focused specifically on eerie or frightening figures. But as the history of Madame Tussauds’ Chamber Of Horrors demonstrates, there’s a reason that specific Chamber Of Horrors was so gut-wrenching: Many of the severed heads and mutilated bodies, although made out of wax, were modeled after actual severed heads and mutilated bodies.

This, it seems, it what happens if you grow up in 18th century France and learn wax figure-making shortly before the French Revolution.

I was maybe nine years old the first time I set foot in a Madame Tussauds. I was fortunate enough as a child to have been able to travel internationally with my family fairly extensively; as such, the Madame Tussauds I visited then was the original one, in London — a city to which I would return several more times later on in life, including for an extended period to live and study in my early 20s.

During that first trip, in the early ‘90s, the London Madame Tussauds location wasn’t just the original one; it was also one of the only ones: The Amsterdam location had opened a few decades prior, in 1970, but the next international one — the Las Vegas location — wouldn’t open until 1999. Given that the network now features a whopping 26 wax museums, all in different cities around the world, that’s… really saying something.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

In any event, this visit to Madame Tussauds London also marked the first time I had ever visited a wax museum, period — and I was entranced. Until I got to the Chamber Of Horrors, that is; at the time, I took the chicken exit, still too afraid of, well, everything to go through that portion of the museum. But for years, I remained fascinated by the exhibit, this land of nightmarish dioramas, the very idea of which I found so frightening I couldn’t actually make myself go through it.

I was lucky enough to be able to see it properly years later — and by then, I knew much more about it. I had read up on it. And the history of the Chamber Of Horrors is as fascinating — and gruesome — as the exhibit itself.

So, this Halloween season, let’s take a look, shall we? Because sometimes, nothing is scarier than reality.

Madame Tussaud’s Early Years And Le Caverne Des Grands Voleurs

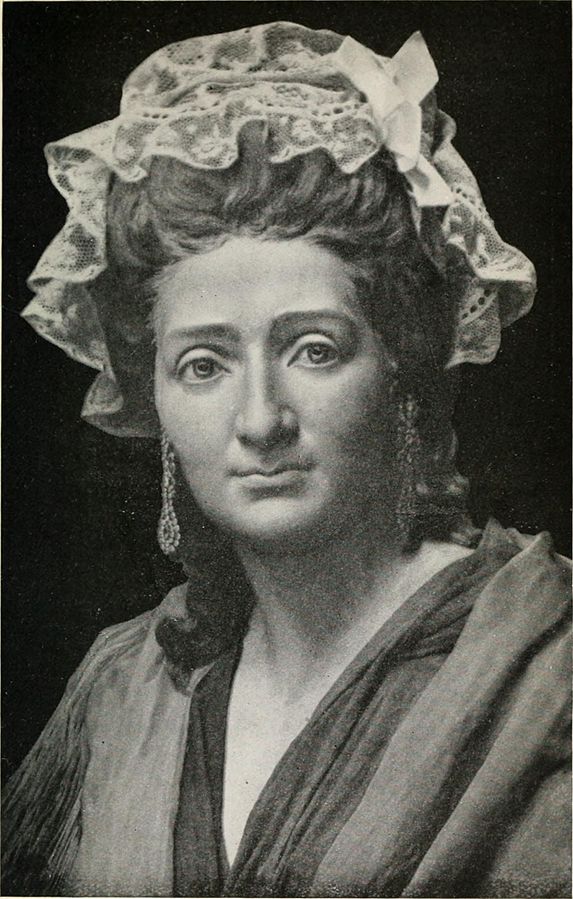

Madame Tussaud’s biography is a little hazy — it’s difficult to know how much of it is mythologizing from the company versus documented fact — but the following is generally accepted as true:

Anna Maria Grosholtz, called Marie, was born on Dec. 1, 1761 in Strasbourg, France, right on border of Germany. Her father died shortly after her birth while fighting in the Seven Years’ War; subsequently, she traveled with her mother to Bern, Switzerland, where they lived with physician Philippe Curtius. Marie’s mother, Anne-Marie Walder, was Curtius’ housekeeper. (Some sources omit the bit about her father dying in the Seven Years’ War; one even posits that Curtius might have been her father. This is what I mean by her bio being hazy.)

In addition to his skills as a doctor, Curtius also had a talent for sculpture, which he used to create anatomical models out of wax for use in his profession and as teaching tools for medical students. He did, however, also occasionally create extraordinarily life-like, three-dimensional portraits of actual people out of wax — and in 1665, he left medicine and moved to Paris to focus on wax sculpting full-time, thanks to the patronage of Louis François I, Prince de Conti.

Marie and her mother followed, and in Paris, Curtius soon took on an avuncular role for Marie. When he realized she, like he himself, had a talent for sculpture, he began teaching her how to create waxwork figures herself. She learned quickly, and soon demonstrated her own skill: In 1777, when she was just 16, she completed a sculpture of writer and philosopher François Voltaire celebrated for its accuracy. Her skills would be lauded enough that the royal family eventually hired her to teach them art.

Curtius began displaying his work around this time, opening several exhibitions between the late 1760s and the 1790s. One, his Salon de Cire, which featured famous figures of the time such as writers, thinkers, and members of the royal family, quickly became a fashionable form of entertainment — but it was a later venture that became a true hit. Noticing how morbidly entranced people from all social backgrounds and strata were by public executions, noted historian and writer Geri Walton at her website in 2018, he wondered what might happen if he created a wax exhibit that allowed people to get up and close and personal with what the court system deemed the dregs of society. So, he created le Caverne des Grands Voleurs — the Cavern of the Great Thieves. Here, visitors would see figures of convicted criminals who had, as I put it back in 2020, “met with a sticky end courtesy of the friendly neighborhood executioner.”

People ate it up — and it’s something that would stick with Marie for years to come.

Then the French Revolution began, and heads literally started to roll — heads which, famously, Marie would immortalize in wax, although not always by choice.

As Emma McEvoy points out in the 2016 book Gothic Tourism, quoting from Pamela Pilbeam’s 2003 book Madame Tussaud And The History Of Waxworks, Marie “undertook the gruesome labor of modelling the severed heads of enemies of the Revolution for the Convention” for both propaganda and record-keeping purposes — death masks which, often, belonged to people she actually knew personally. Perceived as a royalist, she herself was eventually arrested, although she did manage to escape the revolution with her own head still firmly attached to her shoulders.

Curtius died in 1794, leaving his extensive collection of wax figures to Marie. Marie then married a year later, in 1795. Although the marriage wasn’t a strong one — the couple was estranged for most of their lives — Marie’s husband, François, did give her the name by which should would eventually be remembered: Tussaud.

Madame Tussaud In London: From The “Separate Room” To The Chamber Of Horrors

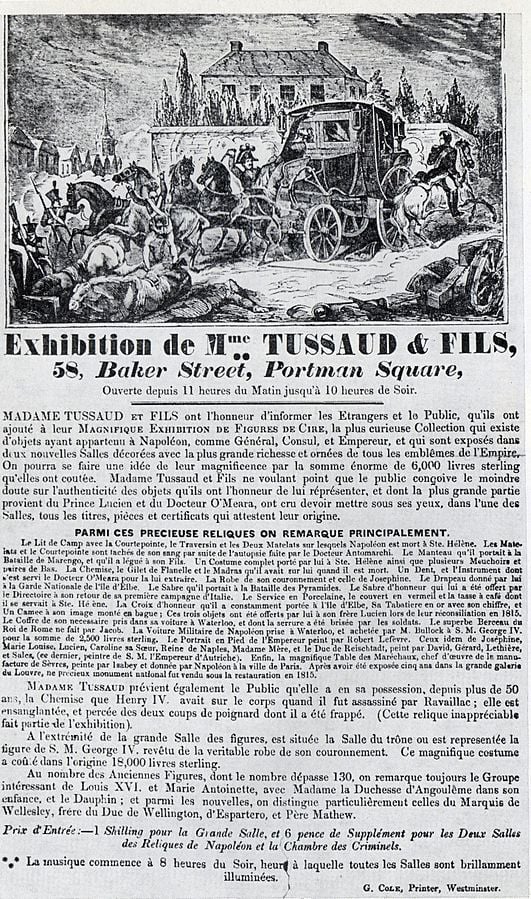

In 1802, the recently-minted Madame Tussaud left France with one of her two sons, then-four-year-old Joseph, for England, where she would reside for the rest of her life. She also began displaying her wax figures at this time — first in tandem with phantasmagoria performer Paul Philidor, then on her own in a touring exhibition, which she would travel with throughout the UK for 33 years.

Like many wax figure exhibitions at the time, part of her collection encompassed well-known public figures — politicians, musicians, writers, and other celebrities of the day — but what set Tussaud’s show apart was the extensive collection of figures of the French Revolution, nearly all of whom were depicted not as they had been in life, but how they looked at the moments of their deaths. Writes Emma McEvoy in Gothic Tourism, “Tussaud’s bleeding heads were spectacles of mortality, records of a very bloody, and very recent history.” Furthermore, continues McEvoy, “Tussaud did not present this narrative in the mode of tragedy, but in the mode of horror — the reduction to pulped flesh.” Her figure of Robespierre, for example, “showed not only the severed head, but the bloodied broken jaw, result of a gun-shot wound, that had him screaming at the guillotine.”

Initially, all of Tussaud’s figures were displayed in the same room. Eventually, however — not dissimilar to her mentor Curtius’ Caverne des Grands Voleurs — she began displaying the more gruesome figures in a second room. Called, variously, the Separate Room, the Adjoining Room, the Other Room, the Dead Room, and the Black Room, this second space required an upcharge of six pence to see. Visitors who shelled out the additional fee witnessed the death masks of figures such as Robespierre, Jacques Hébert, Antoine Quentin Fouquier-Tinville, Jean-Paul Marat, and Jean-Baptiste Carrier.

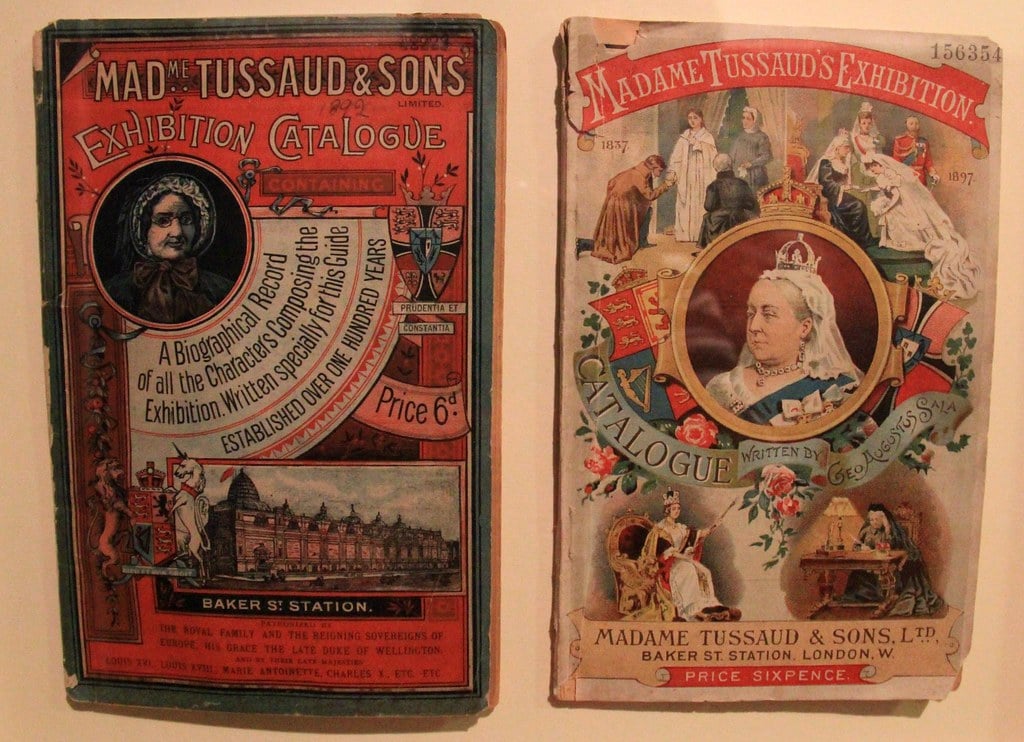

In 1835, Madame Tussaud, along with her then-grown sons, Joseph and François, set up the first permanent exhibition of her work in London. Located on Baker Street, this exhibition, too, included the “Separate Room”; soon, though, it would earn a different name: The Chamber Of Horrors. Tussaud herself coined the phrase — it first appeared in one of the catalogues that accompanied the exhibit around 1843 — but when the magazine Punch utilized it a few years later, it quickly became a household name.

Over the years, Tussaud modeled more subjects for her Chamber Of Horrors: Colonel Edward Marcus Despard, who was caught plotting with six co-conspirators to take over the Bank of England and the Tower of London and assassinate George III in 1802; Burke and Hare, the infamous body snatchers and murderers responsible for killing 16 people and selling their bodies to anatomist Robert Knox in Edinburgh in 1828; and Catherine Wright Stuart, who poisoned farmer and merchant Robert Lamont in 1829, among others. The Chamber Of Horrors also contained a working model of a guillotine — and, eventually, an authentic guillotine blade used for executions during the Revolution was displayed on the wall, as well.

The blade is often said to have been the one to have executed Marie Antoinette, although as the Madame Tussauds Archive website now notes, there’s actually “no solid evidence of its connection to the ‘let them eat cake’ queen’s death.” (Also, fun fact: Marie Antoinette probably did not actually say, “Let them eat cake.”) Regardless, it did have quite the bloody history; Madame Tussaud’s son Joseph purchased it sometime in the mid -1800s from Clement Henri Sanson, the grandson of Reign Of Terror executioner Charles Henri Sanson.

The Chamber Of Horrors fascinated visitors of Madame Tussaud’s Baker Street exhibition — and continued to do so after her death in 1850, and after the exhibition’s move to its current location on Marylebone Road in 1884. It was even updated regularly, just as the rest of the museum was — and in 1996, it received an extensive refurbishment, giving it the appearance it would maintain for the next two decades.

The Chamber Of Horrors Through The Years

As I noted in my introduction, I regretfully didn’t actually see the Chamber before the refurbishment, despite the fact that my first visit to Madame Tussauds occurred when it was still up. Happily, though, a 1975 guidebook to Madame Tussauds which has (perhaps somewhat improbably) wound up on YouTube includes a detailed section on the Chamber Of Horrors at that time, giving us a peek at what it looked like.

There is, as you might expect, a particular emphasis on the French Revolution; Marat in his bathtub, the guillotine model, and Marie Antoinette’s death mask occupy the first few pages. Next, we enter the serial killer section, followed by a display of a gallows used at Hertford Gaol that dates back to 1824. Lastly, there’s a section on the Battle of Trafalgar, the scene of which was originally put into the Chamber Of Horrors in 1966.

The images of this version of the Chamber Of Horrors suggest something a little bit different than what would be on display after the 1996 refurbishment. There’s blood, of course — but the environments in which the models are displayed seem to be a bit tamer than they would later become: For instance, serial killer John Christie is displayed in his kitchen. Of course, if you’re familiar with Christie’s history, you’ll know that this kitchen is where he hid the bodies of the eight people he killed in the 1940s and ‘50s — but all we see is the kitchen. Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen, meanwhile (who may have been innocent after all?), is shown in the dock at court.

Post-1996, though, I had several opportunities to witness the refurbished version. Located (where else?) in the basement, all done up in blood reds, deep blacks, and expressionistic angles, this version seemed engineered for maximum horror.

After descending a dizzying array of stairs, a figure of Vlad the Impaler greeted you at the entrance. As you continued on, you’d see someone being garroted, someone else stretched on a wheel, and various other people suffering horrible forms of torture. You’d watch pirates being executed, and see Guy Fawkes hung, drawn, and quartered. You’d encounter murderers and serial killers, including Christie and Crippen, this time trapped behind bars and headed for execution. And, of course, you’d see scenes and artifacts from the French Revolution: A young Marie Grosholtz sifting through a pile of bodies at the base of a guillotine; heads on stakes — Robespierre, Marie Antoinette, Hébert, the lot; the guillotine blade, claiming to be the one responsible for Marie Antoinette’s death, hanging on the wall behind glass.

The whole space was like a penny dreadful come to life, bold, unflinching, and, above all, bloody. Very, very bloody.

When I moved to London in 2006, I took myself back to Madame Tussauds again, partially out of nostalgia and partially to see how the place had changed since the last time I had been there. This time, I surprised to find that an addition to the Chamber Of Horrors had been added: The Chamber LIVE!, which was essentially a walk-through haunted attraction featuring a maze of close corridors and live actors.

It’s very, very difficult finding documented information about the walk-through haunt these days, despite the fact that it ran for over a decade when the age of the internet was well under way; there were strict no-recording-of-any-kind rules for visitors, so the inside of it has not, to my knowledge, been sufficiently documented.

From what I’ve been able to tell, though, it seems to have launched sometime in the early 2000s — the earliest documentation of it on the Madame Tussauds website is dated December of 2003. The Chamber LIVE! may have been the first iteration; I recall it being sort of a general haunted house, although as time went by, it would change a number of times, with new themes and names to keep visitors coming back. The longest-running version seems to have been SCREAM: One Way Out, an “Oh no! You’re trapped in a maximum-security prison where all of the inmates have escaped!” scenario, which had been implemented at least by 2008 and stuck around for the next seven years or so.

International Thrills And Chills

But what of the international locations? After Madame Tussaud began its rapid expansion in the late 1990s and early 2000s, did any of these other locations incorporate the Chamber Of Horrors?

Yes and no. Variations did exist in at least a few of the global locations; however, none of them were anything like Madame Tussaud’s original Chamber Of Horrors. Rather, they were nearly all live walkthrough haunted attractions cast from the same mold as the Chamber LIVE and SCREAM.

I saw a couple of them in New York; that branch of Madame Tussauds opened in 2000, just a few years before I moved to the city in my late teens. In the mid-2000s, for instance, there was a walkthrough themed to the 2005 remake of the film House Of Wax. (Fitting, no?) Several years later, there was still a haunt within the museum — I actually knew someone who worked in it as an actor — but although I did walk through it once sometime circa 2009, I honestly couldn’t tell you what the theme was. The Wayback Machine suggests it was sort of a general horror movie experience called, like the later London iteration, SCREAM — but it was apparently unmemorable enough that I have no recollection of what it was like. I do recall seeing almost no actors during my walkthrough, though, so it’s possible I just caught it at an off moment.

Several other branches of Madame Tussauds, including the Las Vegas, Shanghai, and Hong Kong locations, also had walkthrough haunted attractions in the late 2000s and early 2010s; they, too, seem to have been modeled after SCREAM, and in one case — the later years of the Las Vegas one — appears to have been more or less a carbon copy of London’s SCREAM: One Way Out. Periodically, too, there were “After Dark” events in Las Vegas and New York — special Halloween events that would see visitors walking through the museum with lights out after regular operating hours had ceased, using only a flashlight to light their way and encountering the occasional actor leaping out at them as they went.

Curiously, though, these walk-through haunts only popped up in a few of the numerous Madame Tussaud locations. Many of them — Amsterdam, Berlin, Blackpool, and more — seem never to have jumped on this spine-chilling train, although it’s not clear why. My guess would be that it had something to do with specific regions and cultures not being quite as into the idea of haunted attractions as others, but that’s pure conjecture on my part.

The End Of An Era

Alas, as of this writing, the Chamber Of Horrors and accompanying live haunts have been removed from most, if not all, iterations of Madame Tussauds around the world.

New York’s last version of SCREAM seems to have closed by the end of 2013, as evinced by its sudden disappearance from the Madame Tussauds New York website in 2014. The Las Vegas SCREAM also seems to have closed around the same time; the last time it appeared on that location’s website was in 2013. And the same is true of Shanghai, which had SCREAM on its website from 2009 until 2014.

And in London? At the original Madame Tussauds? The live experienced screamed its last scream in 2015 — and the original Chamber Of Horrors itself closed up shop a year later, in 2016. It was replaced at the time with a Sherlock Holmes experience, although this, too, has since shut its doors. As of this writing, there’s some sort of Alien-related exhibit available that seems to fill the Chamber of Horrors void to some extent, but it mostly just looks like a showcase for the museum’s Michael Fassbender figure.

Why did they all close? That’s anyone’s guess, although I have a theory:

It’s worth noting that a number of the cities in which Madame Tussauds operates also host Dungeon attractions — the London Dungeon, the Edinburgh Dungeon, the York Dungeon, the Amsterdam Dungeon, and so on and so forth. These Dungeon attractions are effectively large, standalone Chambers Of Horror — and, crucially, they are owned by Merlin Entertainments, which also currently owns Madame Tussauds.

The London Dungeon is by far the oldest of the Dungeons; it opened in 1974, founded by Annabel Geddes as a walkthrough exhibition depicting some of the more gruesome aspects of London’s history via waxworks and figures. A second Dungeon, the York Dungeon, opened in 1986 — and in 1992, they were both acquired by Vardon Attractions, which then became Merlin Entertainments at the end of 1998. The Dungeons franchise rapidly expanded soon after; currently, there are 10 Dungeons spread across the UK, mainland Europe, and even Asia — the Shanghai Dungeon opened in 2018.

(Interestingly, there was once also an 11th Dungeon lurking in the brand’s portfolio — the San Francisco Dungeon in Northern California — but after being “temporarily closed” for some time, as well as absent from the main Dungeons website, it eventually closed permanently.)

Over time, the Dungeons have shifted in form; although they were originally quite similar to Madame Tussauds’ own original Chamber Of Horrors, these days, they’re almost more like small, indoor theme parks, full of rides and other interactive experiences. It’s possible that a business decision was made regarding the Chamber Of Horrors based on the prevalence of the Dungeons — that is, since these attractions fill the niche the Chamber Of Horrors occupied and then some, they may have rendered Madame Tussauds’ version obsolete.

That’s just a theory, of course. But it’s not outside the realm of possibility, so do with that thought what you will.

Remnants Of The Past

I won’t lie: I’m a little sad I’ll never be able to walk through the Chamber Of Horrors again. It loomed large in my memory and imagination for literal decades, and the thought of such a long-running institution being gone for good is a bit of a melancholy one.

But in this day and age, nothing is truly gone — and if you dig, you can find some remnants of the old Chamber Of Horrors.

In addition to the 1975 guidebook referenced further up, I’ve found two videos converted from VHS on YouTube showing bits of the Chamber in the early 1990s, if you’re curious about what it looked like prior to the 1996 refurbishment. Note, though, that at this time, there was apparently an electric chair exhibit, so there are flashing lights in both of them. If you’re photosensitive, you might want to skip them; if you’re not, though, you can find them here (skip to the 10:21 mark) and here. (Again: Flashy lights warning for both of those videos!)

Additionally, a handful of videos exist showing what the Chamber looked like post-refurbishment for the remaining two decades it was running. Here’s a video from 1998 (skip to 9:50 to see the Chamber); here’s what the entrance to the Chamber LIVE! looked like in 2007; at about the five-minute mark here, you can see the Chamber Of Horrors in 2011, including the entrance to what had by that point become the SCREAM attraction; and these two videos show the Chamber Of Horrors in 2015, the year before it closed for good.

So, this Halloween, why not take a virtual walk through history?

Just… don’t lose your head about it.

If you know what I mean.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And for more games, don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via Karen Roe, mariosp, Pommiebastards/Flickr, available under CC BY 2.0 and CC BY-SA 2.0 Creative Commons licenses; Wikimedia Commons (1, 2)]

Leave a Reply