Previously: Winderbourne Mansion.

Just north of Tokyo — about an hour away by car — lies Saitama Prefecture. Saitama has the fifth largest population by prefecture in Japan; however, outside the major metro area, it also has a number of small towns and villages. Yoshimi-cho is one; it’s widely known for its massive cave tomb system, the Yoshimi Hyakuana (吉見百穴) or the Hundred Caves of Yoshimi, which dates back to around the sixth century BCE. But right next door to the Hundred Caves — and I do mean right next door; it’s just a few hundred meters away — there’s something… else. Something even more curious: The ruins of Gankutsu Hotel (巌窟ホテル), or, as it’s sometimes translated as, the Rock Cave Hotel.

Gankutsu Hotel was never an actual hotel; what’s more, it was never meant to be one, either. When its creator, Takahashi Minekichi (高橋峰吉), began construction on it in 1904, he did it, he said later, not for any “utilitarian purpose,” but for “the satisfaction of pure artistic creativity.” It’s possible, as one Japanese language website on the history of the structure posits, that the place became known by the “hotel” moniker due to the fact that it resembled a large, Western-style building — that is, it reminded those who witnessed Minekichi building it of a Western hotel, and accordingly began referring to it as such. However, another theory states that the name have arisen from what those watching Minekichi constructing the site frequently observed: “He’s digging a cave” (“巌窟掘ってる”). According to this theory, the word for “digging,” pronounced “hotteru,” may have eventually been distorted into “hoteru” (ホテル) — “hotel.” Ergo: Gankutsu Hotel.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

For his part, Minekichi didn’t call it a hotel. He didn’t refer to it as Gankutsu, either. He called it Kosokan (高荘館) — a name he stuck with for the entire 21 years he worked on it.

Minekichi was born in 1858, the child of farmers whose formal education consisted solely of learning the basics of reading and writing at a terakoya (寺子屋) — an elementary school run by the monks at a local temple. Nonetheless, he continued his education on his own, teaching himself a great deal in subjects ranging from physics to philosophy — and including architecture.

So — spurred on, perhaps, by memories of picking wild strawberries and allowing them to ferment in holes he found within the rocks and cliffs of his home as a small child (or perhaps not; it’s been proposed as an inspiration, although not definitively proven) — he came up with a plan: He would chisel into the rockface a glorious building, part dwelling and part art installation, for no other reason than just the fact that he could. He wanted to do it; so, he did.

Minekichi’s original plans depicted a three-story building with a frontage of about 20 ken, or roughly 36.4 meters. (Ken is a traditional unit of length in Japan; the traditional units of measure have largely been supplanted by the metric system these days, but you’ll still occasionally find them in use in certain situations — ken, for instance, is still used in architecture.) Interestingly, the building also had a balance between its width and height that was quite close to the Golden Ratio, although it’s not clear whether that resemblance was intentional or simply a happy accident. He stated that he intended the place to embody the Romanesque architectural style popular in Europe during the sixth to the 12th centuries.

What he ultimately built, though, was only two stories, and although there were certainly Romanesque elements, it was also distinctly Japanese. That’s not necessarily a failing, of course; in fact, I’d argue it’s an indication of true art at work: Funneled through the lens of the individual artist, the inspirations became something new and unique.

Minekichi also didn’t fully complete the structure. He did, however, complete an astonishing amount of work, given that he kept at it alone with little more than a chisel: Over the course of 21 years — from 1904, when Minekichi was about 46 years old, until his death in 1925 at the age of 67 — he carved a central hall, a laboratory, staircases, and a balcony. What’s more, it’s likely he never intended to finish it in his lifetime; he said at one point that he estimated his plans would take 150 years to construct.

After his death, Minekichi’s son took over construction, and for a time, Gankutsu Hotel even had the cachet of being a major tourist attraction. This moment in the spotlight was short-lived, however; the site was shut down during the Second World War and repurposed, along with the nearby Hundred Caves and the now-destroyed Matsuyama Castle, for use as military factory for aircraft engines. It reclaimed its status as a sightseeing spot following the war, this time maintaining its reputation for several decades until a run of misfortune in the 1980s and ‘90s shut it down for good: First, it was damaged by not one, but two different typhoons — one which struck in 1982, and the other in 1987; and then, sometime around 1990, Minkechi’s son died. Construction, repairs, and upkeep all halted, and gradually, the forever-in-process project grew to be not just incomplete, but haikyo (廃墟) — abandoned, ruined, lost to time and decay.

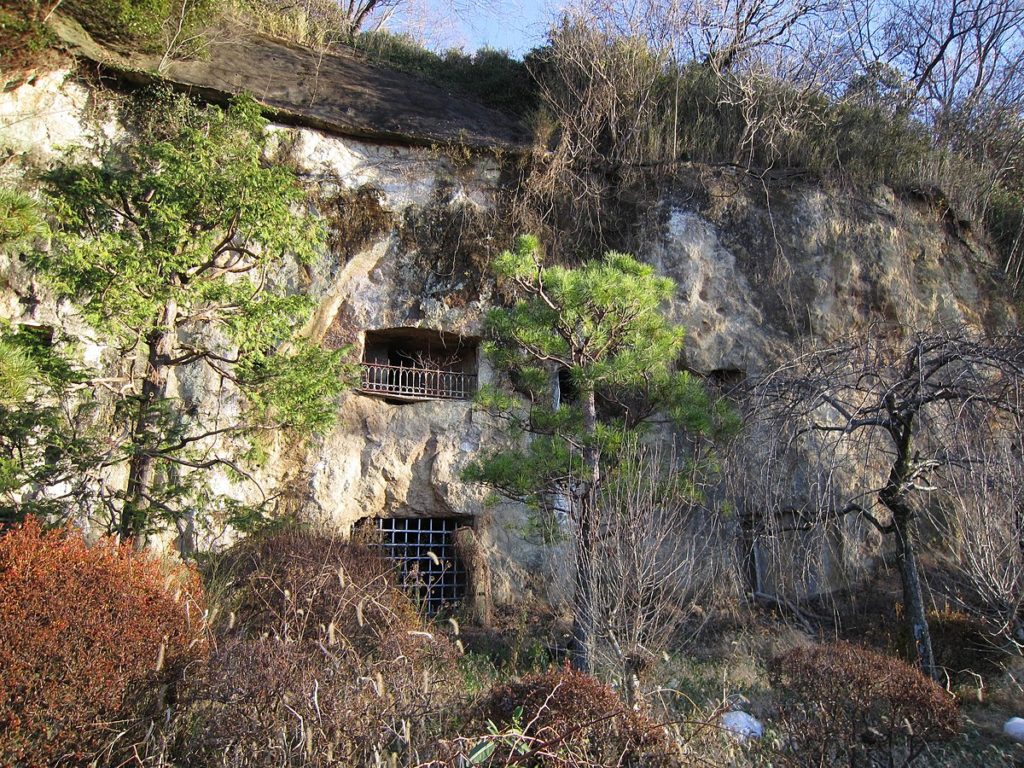

Today, the unfinished remains of Gankutsu Hotel still sit in Yoshimi-cho in full view of the road by which they lie. They’re fenced off, and behind the chain link and barbed wire, they’re overgrown — so much so that during the warmer months, the greenery almost hides them from sight. If you look carefully, you’ll see several entrances blocked by metal gates or portcullises; you’ll see the balcony up on the second story, also adorned with a decorative metal safety railing; and on the grounds out front, you might see a curious, sphere-like object made of metal framing. It’s not clear to me what precisely this item is, but it looks as if it may have, at one point, been a child’s jungle gym.

The ruins of Gankutsu Hotel are not open to the public — but that hasn’t stopped a number of urban explorers for sneaking onto the property and exploring anyway. The site is a much-beloved haikyo, and much easier to locate and reach than, say, the Maya Kanko Hotel in Kobe (which, unlike Gankutsu, actually was a hotel at one point). Finding photo essays online from those who have gone spelunking inside Gankutsu isn’t difficult, if you know where to look; you’ll have more luck searching in Japanese than English, but there’s plenty to see if you’re persistent in your research.

It’s not recommended that you try to sneak into Gankutsu hotel yourself, though. It is, after all, private property, and believed to be owned still by Takahashi Minekichi’s descendants. If you go: Look, but don’t touch. Drive or walk by, but do not linger. And definitely — definitely — don’t try to hop the fence.

But you know what you can visit? The Rock Cave Shop (岩窟売店). Located right next door to the Rock Cave Hotel itself, it’s a noodle shop and tea house that is, in fact, run by the Minekichi family — and if you go inside, you’ll be able to see a variety of documents and artifacts pertaining to Takahashi Minekichi and his Gankutsu Hotel. His original rendering of his grand scheme is on display here; go on and take a look. There’s also soba, udon, tea, and coffee to be had, all delicious, and all at an incredibly affordable price, according to those who have been.

So: If you’re in the area, stop by. Have a snack or a cup of tea. Think for a moment about what you hope to accomplish in your lifetime. And when you pass by what was once a simple cliff face, and is now something extraordinary, ask yourself:

If not now, when?

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via Qurren (1, 2)/Wikimedia Commons JP, available under a GNU license; puffyjet/Flickr, available under a CC BY 2.0 Creative Commons license]

Leave a Reply