Previously: Tarot Cards.

I couldn’t tell you when I learned that palm-reading existed; due in large part, I think, to the kinds of stories I developed an interest in at an early age, knowledgeable mystics able to use the palms of peoples’ own hands as a window into the unknown have been a part of my mental landscape for pretty much as long as I can remember. But how palmistry actually works? That’s — perhaps oddly — not something I’ve ever spend a ton of time diving into. Like many, I’ve long known the basics — head line, life line, heart line; lumps and bumps and fleshy bits — but how, really does it work? Where does it come from? And, perhaps most important, what can it tell us about ourselves, really?

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

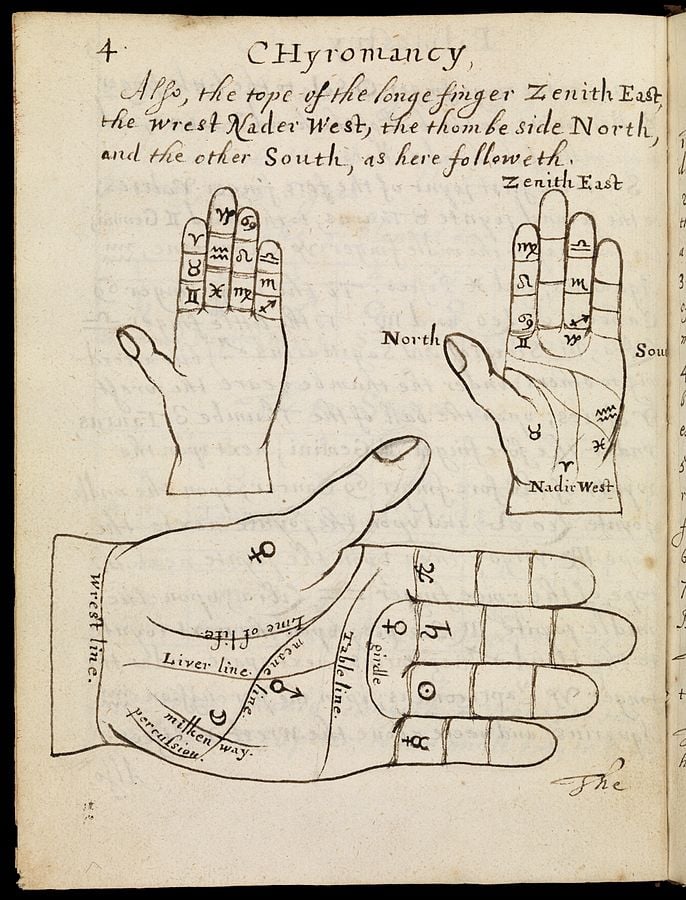

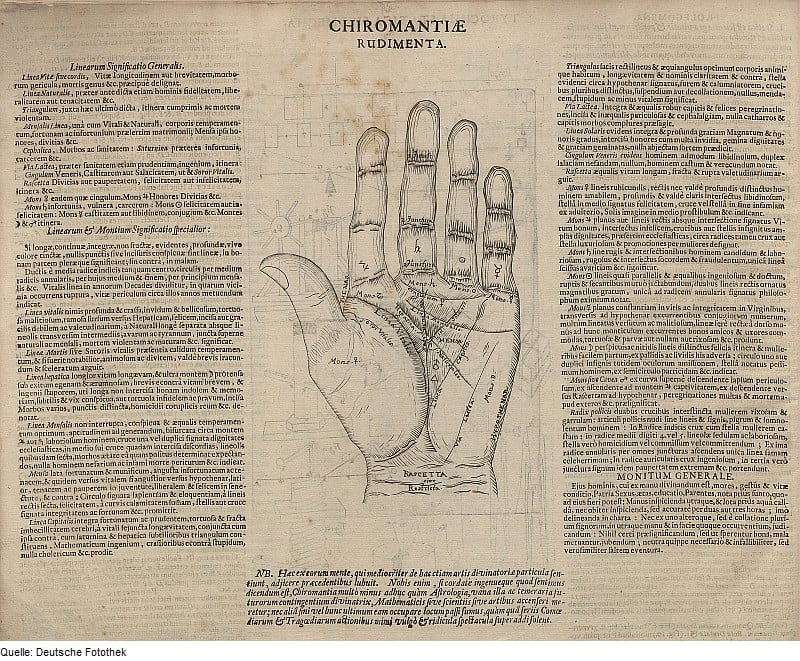

That’s the headspace I was in when I started researching this piece — and I found lots of surprises along the way. I didn’t, for example, expect it to go quite as far back in history as it does. Unlike tarot, which likes to pretend it’s ancient, but isn’t really, palmistry — sometimes called chiromancy, from the Greek kheir (χειρομαντεία, hand) and manteia (μαντεία, divination) — really is ancient. It’s so ancient, in fact, that the origins of it remain somewhat shrouded in mystery.

Here’s what we know about it. Here’s how palm-reading is done. And here’s how it works — both according to those who believe it does work, and to those who believe it doesn’t.

A Brief History Of Palmistry

There’s a lot — a lot — we don’t know about the early history of palmistry. Numerous theories exist about where precisely it originated, but honestly, we have no real idea which one, if any, is accurate. Heck, it’s even possible that more than one is accurate; it’s not unheard of for similar ideas to develop in dramatically different geographic areas, independently of one another. (Hi there, calculus.)

In any event, evidence of chiromancy has been found dating back to such times and locations as ancient India, China, and Greece. Some of the earliest surviving mentions of palmistry can be found within two texts from India — one religious and one legal. In both the Vasistha Dharmasutra and the Manusmriti, it’s stated that ascetics are not to make a living from or participate in activities involving astrology, with palmistry specifically called out as something to avoid. The Vasistha Dharmasutra, named for the Rigvedic sage Vasistha, is thought to have been composed prior to the year 100, and possibly dates back as far as 300 BCE; meanwhile, the Manusmriti is currently believed to have been written sometime between 200 BCE and 200 CE.

It’s also believed that palmistry was known in China during the Zhou dynasty, which spanned from 1046 BCE to 256 BCE; however, the first notable work about palmistry, written by Xu Fu, didn’t appear in China until the Western Han Dynasty, which spanned from 2020 BCE to 9 CE.

Meanwhile, in the West, no full treatises on palmistry from before the Middle Ages have survived, although Aristotle does mention something that suggests knowledge of palmistry in his 350 BCE work Historia Animalia (The History Of Animals): In the 15th part, Aristotle writes of human anatomy, “The inner part of the hand is termed the ‘palm,’ and is fleshy and divided by joints or lines: in the case of long-lived people by one or two extending right across, in the case of the short-lived by two, not so extending.” Apocryphally, it’s said that Aristotle once discovered a treatise on palmistry on an alter dedicated to Hermes, learned from it, and passed its teachings onto Alexander the Great — but there’s little to no evidence that this ever actually happened and may therefore be considered more of a legend than anything else.

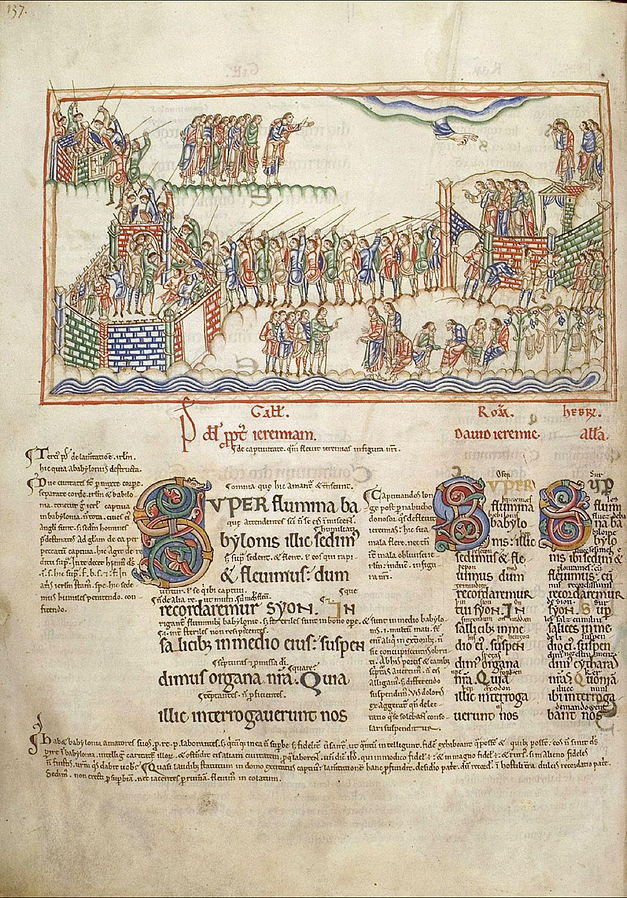

There’s a huge gap in the literature concerning palmistry between these early mentions and the 12th century CE. Indeed, according to Charles S. F. Burnett’s article “The Earliest Chiromancy In The West,” which was published in the Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes in 1987 (which, yes, means it’s old, although it’s actually still quite useful), there aren’t even any references to palmistry in Latin works between the classical era and the mid-12th century. But then, suddenly, not one, but two works concerning chiromancy appear at roughly the same time: John of Salisbury’s Policraticus, which was completed in 1159, and the Eadwine Psalter, written around 1160.

It’s here, too, that we find the first real description of how chiromancy was actually performed at the time: The Note on Chiromancy within the Eadwine Psalter contains, as historian Alexandra Nagel put it at the Leiden University Institute of Philosophy’s Thauma Graduate Journal in 2017, “which signs in the palm indicate particular trades, illnesses, a long journey, conversion, the cause awaiting a person’s death, and so on.”

It’s worth noting that the form of chiromancy described in the Eadwine Psalter is, as Burnett’s article notes, “not unknown”; something similar appears in other manuscripts from the era. But, writes Burnett, “the readings of [the Eadwine Psalter] seem to be more dependably than those of any other manuscript,” despite the fact that it lacks the illustrations and diagrams of hands that other manuscripts hold.

(The Note on Chiromancy was reproduced in whole as an appendix to Burnett’s article, by the way; it can be read for free over at JSTOR.)

Although palmistry actually developed quite a bit throughout the Middle Ages, becoming, per Nagle, “intimately linked to astrology” — elaborates Nagle, “People believed that the characteristics assigned to the heavenly bodies correspond with the human body. Hence, the inner surface of the hand became the ‘interface’ of the macrocosm (heavenly spheres) and the microcosm (human body)” — the Catholic Church, then hugely wealthy and powerful, actively worked to suppress palmistry at this time.

Incidentally, this period also saw the migration of Romani and Jewish populations to the West — both of which for whom chiromancy had long been culturally significant. Divination and fortune telling in the Romani tradition, typically practiced by women known as drabardi, was a source of income when performed for non-Romani people, with palmistry being a particular focus. (Indeed, it’s thought that palmistry’s wide-reaching spread throughout Europe was due in large part to the nomadic nature of the Roma.) Meanwhile, chiromancy has featured in Jewish mysticism since the days of Merkabah mysticism, which was in practice from about 100 BCE to 1000 CE; the earliest known literary mention of chiromancy occurs in a work written in a rabbinic style titled Hakkarat Panim le-Rabbi Yishma’el.

Both groups suffered a great deal of discrimination and persecution at the hands of the Catholic Church (and, by extension, the developing Christian society), so it’s perhaps unsurprising that the Church doubled down on its suppression of palmistry at a time when groups it already didn’t like, and for whom chiromancy was meaningful, were moving West — a geographic location the Church considered “their” territory.

Public interest in palmistry ebbed and flowed for a number of centuries, seeing periodic revivals, such as during the Italian and English Renaissances. But it was the 19th century that really changed things: That’s when the Spiritualist movement kicked up, fueling in the general public both a keen interest in subjects such as divination and parapsychology and the desire to investigate these subjects using scientific methods (and also have fun while doing it). Palmistry comprised one of the many disciplines those involved with the movement chose to focus on — only now, there was move away from the term “chiromancy,” which implied magic, and toward “chirology,” which implied science.

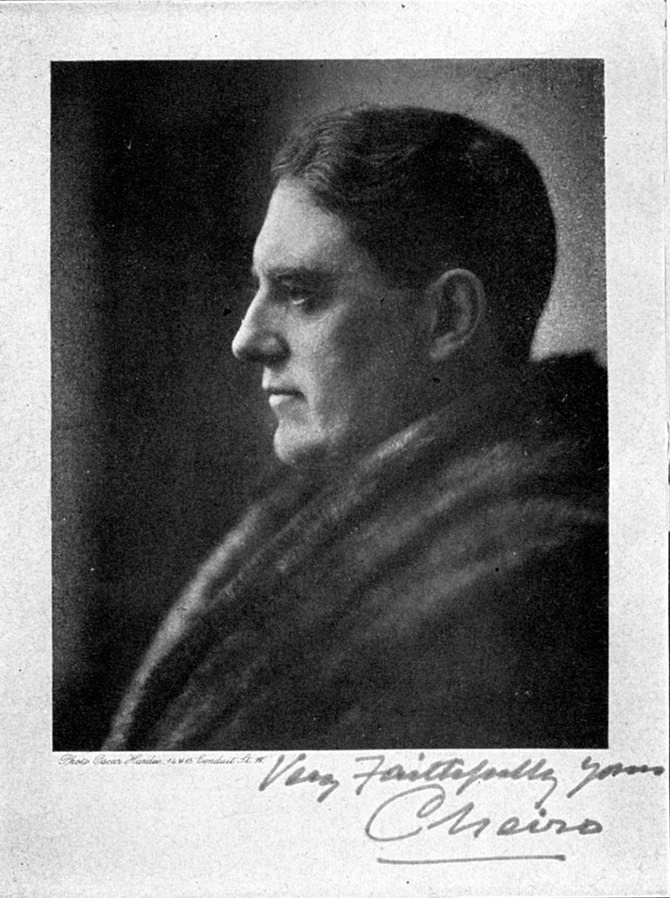

In France, Casimir Stanislas D’Arpentigny’s 1839 work La Chirognomie codified much of what’s still part of modern palmistry now. In England and the United States, the founding of the Chirological Society of Great Britain in 1889 and the American Chirological Society in 1897 represented concrete steps in attempting to develop a universal system for palm-reading. And Irish astrologer William John Warner — better known as Cheiro — became a celebrity in the world of the occult throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, with his many books, including Cheiro’s Language Of The Hand and Palmistry For All, bringing palmistry to the masses.

Palmistry is, of course, still practiced today; in its current form, it has much in common with the variety practiced and refined throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. So how does it work? And, perhaps more pressingly, does it work? Let’s take at both sides of the coin, starting with those who believe in its efficacy.

The Believer’s Argument

Before we can talk about the mechanism by which palmistry works, we need to talk about how it’s actually performed.

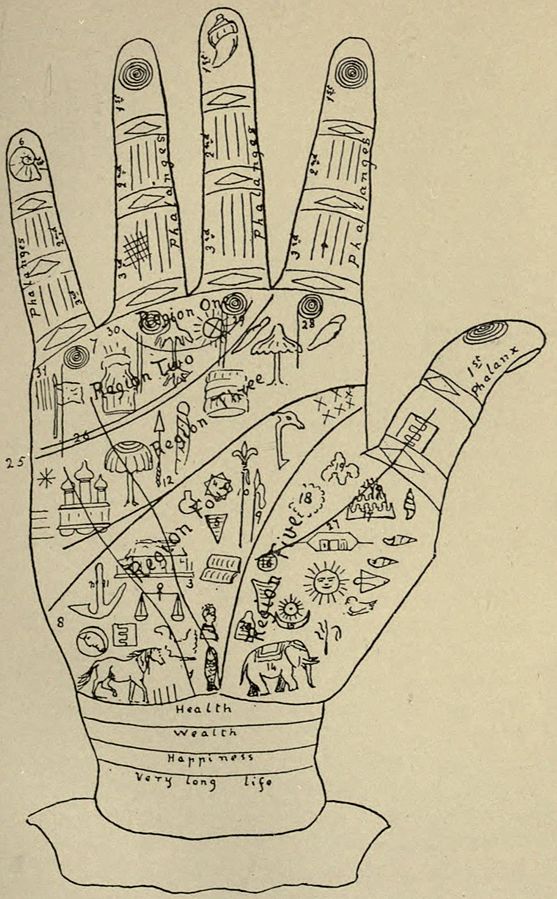

First, we have to consider the choice of hand used for the reading. Both your dominant and non-dominant hands can be read using palmistry; indeed, some practitioners believe that a complete reading must necessarily incorporate both hands. The non-dominant hand is said to represent your inherent potential, personality, and character, while the dominant hand is said to represent how you’ve harnessed those inherent qualities and abilities. When they’re read together, they’re said to be able to give you a full picture of where you’ve been, where you are, and where you might be going.

Next, we move onto the main attraction. The two primary aspects of palm-reading concern the shape of the hand and the creases on the palm. There isn’t one single, unified system for identifying hand shape, but you’ll often find styles of reading that file hand shape under four categories: Hands with long palms and short fingers; hands with square palms and short fingers; hands with square palms and long fingers; and hands with long palms and long fingers. Sometimes, these shapes have names reminiscent of several traits of the Myers-Brigg personality type indicator (intuitive, practical, thinking, or feeling) while others, they’re labeled according to the natural elements (fire, earth, air, or water).

Regardless as to how you refer to them, though, the meanings of the shapes are often similar, reflecting specific character traits of the people to whom they belong. If you have long palms and short fingers, for example, you’re believed to be passionate, hard-working, and a skilled communicator; however, you also might let your emotions get the best of you sometimes. If you have square palms and short fingers, you’re said to be logical and reliable, but you might get a little too hung up on details from time to time. If you have square palms and long fingers, you’re also said to be logical, as well as naturally curious — but on the flip side, you need constant stimulation, or else you get bored and anxious. And if you have long palms and long fingers, it’s believed you’re sensitive and creative, although prone to stress and anxiety.

These aren’t the only ways a hand shape might be classified, though; some systems use only three types (for example, round, square, or rectangular), while others use five. The method of analysis for hand shape depends largely on the reader — what speaks to them, who taught them palmistry in the first place, and so on.

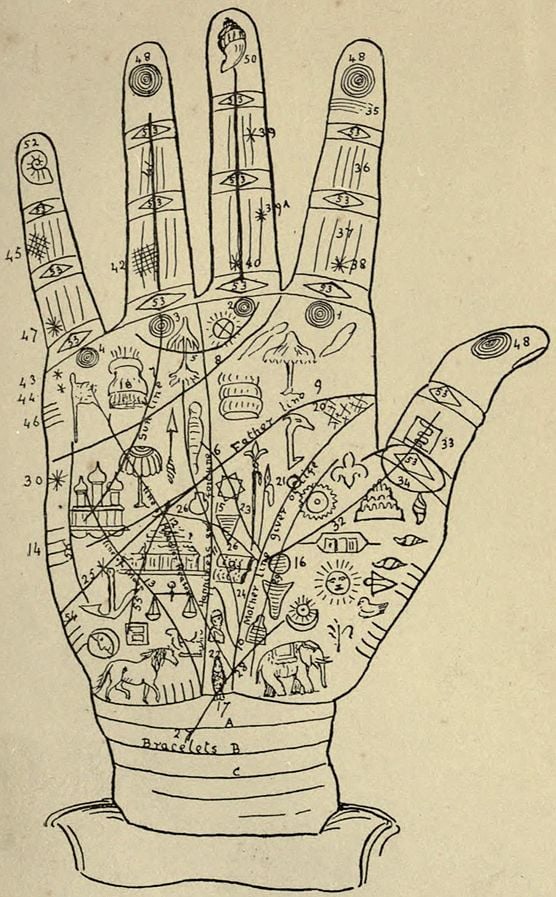

Then, there are the creases in the palm — the lines, as they’re usually called. If you look down at your own palm, you’ll see three prominent lines, along with many more that are smaller and less pronounced. The prominent lines are these: The life line, which begins between your thumb and your index finger and curves down towards the base of your thumb; the head line, which also begins between your thumb and index finger, but cuts horizontally across your palm instead of heading sharply downward; and the heart line, which begins somewhere near the base of your index or middle finger and cuts horizontally across your palm, above the other two lines.

Like hand shape, the details of these three lines are said to tell you much about yourself — although possibly not in the ways you think. The life line, for example, doesn’t’ reveal how long you’ll live; rather, it’s perhaps best described as indicative of your quality of life — your physical health, your mental and emotional well-being, the strength of your interpersonal relationships, and so on. The head line, meanwhile, doesn’t necessarily represent how smart you are — but it might tell you something about your intellectual strengths and weaknesses, how regimented or free-flowing your thought processes tend to be, and more. And the heart line? Yes, it has a lot to do with the romantic partnerships in your life — but it’s more about how you tend to approach romantic relationships, rather than any pronouncement on how “lucky” or “unlucky” in love you’ll be. The length, depth, and patterns of the lines are what you’re meant to pay attention to; it’s through these attributes that the meanings of the lines become clear.

But although many palm readings focus primarily on hand shape and these three lines, the details of each hand matter, too. As Malia Wollan noted at the New York Times Magazine in 2017, “Don’t overlook anything in this tradition; even scars and manicures have meaning.” (Wollan writes the Times Magazine’s “Tips” column; for her piece on palm-reading, she spoke to Mark Seltman, who has been practicing palmistry for about 40 years.)

You might, for example, take a look at your individual fingers. They’re usually named for planets or other celestial bodies; your pinky is tied to Mercury, your ring finger to the Sun, your middle finger to Saturn, and your index finger to Jupiter. Then there are the mounts — the fleshy bumps across your joints and along the plains of your palm. You might also have a fate line, or a marriage line, or other markings made by smaller creases on your palm. They all mean something, according to those who believe in or practice palmistry; for the most thorough reading, let nothing go unnoticed or unremarked upon.

The “how to” is all well and good, of course — but the question still remains: How does it work, exactly? By which I mean this: In the case of, say, talking boards, the devices are said to work by those who believe in them because they essentially yield control to spirits or other entities, giving them something to harness through which they can communicate. It’s like giving someone a pen and a piece of paper so they can write a letter, except that the pen is a planchette, the paper is the board — and the hand used to “write” the “letter” is your own.

The mechanism behind palm-reading isn’t quite that cut-and-dry — and, truthfully, depends largely on the person doing the reading.

For astrologer and occultist Aliza Kelly Faragher, palmistry is “a microcosm of the universe.” As she wrote at Allure in January of 2020, the skill itself is “the art of analyzing the physical features of the hands to interpret personality characteristics and predict future happenings”; she states that, similarly to how ancient astrologers examined the movement of the planets and connected them with what was going on in their own world, palm readers “observe how the hand’s attributes connect to greater themes,” per Faragher. “Occult traditions are based on the esoteric axiom ‘As above, so below,’” she writes — meaning that “what happens on one level of reality also happens on every other level,” too. Palmistry is, in this sense, one way to access the macrocosm, with the palm forming the microcosm.

For others, though, palm reading is more like a language. You don’t even necessarily need to be psychic in order to do it. Although some practitioners of chiromancy note that it does help to have some psychic leanings or abilities, palm-reader Helene Saucedo noted to Well and Good in 2019 that “anyone can read palms — it’s all visual and tangible.” As is the case with learning, say, Latin, or German, or Japanese, it’s true that some people might have a greater aptitude for the language of palmistry than others; still, though—anyone can learn it, and even become fluent in it, per Saucedo. When she reads palms, said Saucedo, “I’m not receiving information from spirits or anything. I’ve just learned the language from the lines on your hand.”

Every palm-reader has a different view of how it works; should you decide to take up the practice of palmistry, you’ll have to decide what it all means for yourself.

The Skeptic’s Argument

When it comes to the skeptical view of palmistry, the answer to the question, “How does it work?” is short and succinct: It doesn’t. Not really, at least. The argument usually relies on the fact that there’s no scientific evidence to support any correlation between the attributes of people’s palms and their personality traits or other characteristics — and, at its most cynical, accuses those who practice palmistry of conscious deception or con artistry.

The biggest strike against palmistry, though, is the line some have drawn between it and physiognomy — physiognomy being the practice of assessing people’s personality traits or characteristics based on their physical features. Physiognomy tends to focus more on the face and head, but the fact remains that, like physiognomy, palmistry relies on the analysis and interpretation of physical features to extrapolate at length about a person’s path through life.

There are a lot of problems with physiognomy. It tends, for example, to assign moral significance to physical characteristics that, in reality, have nothing to do with morals at all. Consider Cesare Lombroso, a major player in the burgeoning field of criminology in the 19th century: According to Lombroso, people with pronounce jaws, low sloping foreheads, full lips, or several different kinds of noses (flattened, upturned, and hooked, for instance) were “born criminals” — that is, if you had any of a certain set of physical characteristics, you were inherently criminal by nature.

That’s, uh, absolutely not true, of course — but we still see this kind of thinking alive and well in just about every harmful and inaccurate stereotype hung off of specific physical features today. (To wit: People with blonde hair aren’t inherently stupid; people with red hair aren’t inherently angry all the time; fat people aren’t inherently lazy; Black people aren’t inherently “thuggish”; East Asian people aren’t inherently academic wizzes; and so on and so forth.)

Related is the fact that physiognomy has historically been used to support scientific racism. (This should be unsurprising if you looked at Lombroso’s ideas on what a “born criminal” looked like and thought, “Gee, that list of features looks… awfully racist.”) Phrenology is perhaps the most the most well-known example. Popular in the 19th century, phrenology claimed that lumps and bumps of the human skull could tell you everything you could ever want to know about the person the skull belonged to. The thing is, it was created by white Europeans, who generally used it to justify why white Europeans were superior to… just about everyone else. As Tom Whyman pointed out at The Outline in 2019, for example, phrenologists “claimed that African skulls had large regions corresponding to ‘veneration’ and ‘cautiousness,’ making them easily ‘tameable’” — that is, phrenologists used their junk science to justify slavery. (Recent scientific research has also found that phrenology has absolutely no basis in reality.)

There are, of course, many ways in which palmistry is not like physiognomy or any of its related pseudoscientific pals (which, really, are more non-science than anything else). It has not, for example, been used historically as a way to justify the oppression of wide swathes of people. But the similarities between it and other, similar forms of now-discredited pseudoscience are hard to ignore, particularly for those who sit on the skeptics’ side of the aisle.

There’s another part to the skeptic’s argument, as well — something that has to do with palm-readers themselves. As with tarot card readers, skeptics of palmistry position palm-readers as people with excellent cold reading and storytelling skills. They’re not tapping into something cosmic that reveals the bigger picture of the world and where your life fits within it; they’re simply observing you carefully and spinning a gripping yarn for you, about you, using the details they’ve picked up without you realizing it. The only difference here is that, instead of using a deck of tarot cards as the lens through which to focus the storytelling, palm-readers use, well, the palms of your hands.

I’ll point over to our piece on tarot cards for a more in-depth rundown of how cold reading works, but as a reminder, the cold-reader’s toolkit features things like the skilled exploitation of the Forer effect — as I put it at the time, the “psychological phenomenon in which people who are given personality descriptions which are actually vague enough to apply to huge swathes of the population rate those descriptions as highly accurate when they’ve been convinced that they were personalized just for them” — along with techniques like shotgunning (“throwing out a number of vague statements, seeing which ones their target picks up on or responds to, and running with them”), asking leading questions, and simply being able to make astute judgments about a person based on how they present themselves.

It’s worth noting here, as I did then, that cold reading isn’t necessarily malicious or performed with the intent to defraud; some excellent cold-readers don’t even necessarily know that they’re doing it. Still, though — the tools are there, and they can be used just as easily in the art of palm-reading as they can with tarot cards, or even just plain ol’ seances or the standard psychic medium schtick.

There might, too, be something else at play: The Skeptic’s Dictionary also suggests that “many of those who think they have found support for palmistry are guilty of confirmation bias and have found it in the form of anecdotes.” Confirmation bias is, as Simply Psychology defines it, “the tendency of people to favor information that confirms their existing beliefs or hypotheses”; in the case of palmistry, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to find that at least some people who believe in its validity have confirmed that belief — a belief they already held — after having an experience, or even simply hearing of an experience, that seems to support it, despite the fact that anecdotes aren’t hard data.

Indeed, as Simply Psychology notes, the effects of confirmation bias are often “stronger for emotionally charged issues and for deeply entrenched beliefs” — and if there’s one thing I know about the occult is that, for those who believe in it, it’s absolutely emotionally charged and often deeply entrenched.

What Do You Believe?

To be fair, there are a lot of things you can tell about a person based on their hands. Whether they’re callused or not, for example, might reveal something about their occupation or their hobbies: Maybe they work in construction, or play a string instrument, or maybe they draw, or paint, or write longhand. Similarly, whether they’re manicured — and if they are, in what style — might tell you something about how they feel about how they like to present themselves: Maybe they like looking polished, or maybe they prefer a neat but otherwise unadorned look. Scars and traces of old injuries, too, can reveal tidbits of information, as can so many other details.

But whether or not you believe those details are tied to the grand scheme of things? Whether you’re an “as above, so below” kind of person, or whether you just believe in the power of observation? That’s something only you can answer for yourself.

Me? I’m not sure where I fall. As you may have noted throughout the entire How Does It Work? series, I lean much more to the skeptic’s side of things than to the believer’s; however, as with tarot card reading, I think there’s at least some benefit to palm-reading — largely because it isn’t necessarily a “psychic thing,” but more of an “understand yourself on a deeper level” kind of thing.

That said, though, I’ve never actually had my palm read. I’ve had my tea leaves read; I’ve read my own tarot cards; but palm reading? That’s not something I’ve experienced myself — and, alas, probably won’t anytime soon.

One day, though, maybe I will.

When it’s safer to exist in the world again, maybe I’ll find a local palmistry practitioner and pay them a visit.

You never know what could emerge from a session, after all, right?

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via public domain (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6), Ganaahuu/Wikimedia Commons; Wellcome Collection, available under a CC BY 4.0 Creative Commons license.]

Leave a Reply