Previously: The Stone Tape Theory.

They loom large in our cultural landscape: Decks of brightly colored cards, illustrated with the finest of details and seemingly capable of telling us endless stories about ourselves, our pasts, and what might await us in the future. But there’s more to how tarot cards actually work than what most pop culture depictions of the decks and those who use them would have us think—and it’s actually a lot less metaphysical than those depictions show, as well.

That doesn’t mean there isn’t any magic involved. There is; it’s just a… different kind of magic than the sort that emerges from the wave of a wand and the utterance of some complicated-sounding words.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

I was something of a misfit when I was young, and like many people who were misfits when they were young, I took up tarot reading as a hobby during my middle and high school years. (To be fair, I’m still a bit of a misfit now — I was a weird kid who grew into a weird adult. But I’ve embraced weirdness as a way of life, so hey, it all seems to have worked out in the end.) I used the Medieval Scapini deck; although the deck itself was far from medieval (artist Luigi Scapini wasn’t born until 1946), it was beautiful, a Tarot de Marseille deck with a distinctly 15th century vibe to it.

I learned quickly that, for me at least, the cards didn’t hold any sort of mystical ability; but they did offer up a different sort of experience — one I found valuable all the same. Not everyone who has used the tarot has had the same experiences I did, of course, though, so for this edition of How Does It Work?, we’re taking a look at the many, many ways one might go about approaching the tarot.

First: The surprising story of where tarot cards actually come from. (Spoiler: It’s probably not where — or when — you think.)

A Brief History Of Tarot Cards

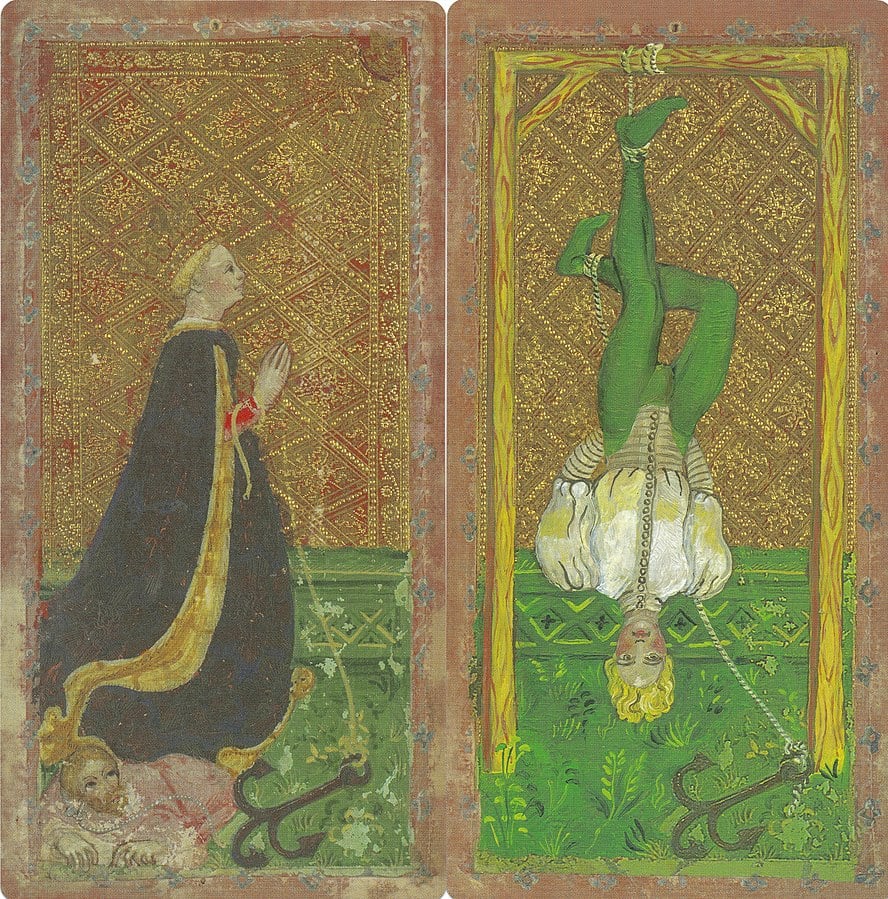

There’s a lot of mythology floating around out there surrounding not only tarot cards themselves, but also their origins and history — much of which is inaccurate. For example, although it’s often said that tarot and its symbolism can be traced back to ancient Egypt, no evidence has ever been located that firmly supports this idea. In fact, tarot is a much, much more recent invention: It began to emerge in the form we know it today during the 15th century. What’s more, tarot cards weren’t originally used as a method of divination; they were simply tools with which to play card games and gamble.

As Sherryl E. Smith notes over at Tarot Heritage, a couple of things needed to happen before tarot cards could become a thing: The concept of playing games with small pieces of paper — that is, with cards — needed to become popularized; inexpensive paper-making and printing methods that allowed for the mass production of decks of cards needed to be readily available; trade networks to sell these mass-produced decks of cards needed to exist; and dense urban populations needed to be around to buy the decks of cards on offer. “All of these conditions came together in Europe, especially in Italy, in the last quarter of the fourteenth century,” Smith writes: The first paper mills sprang up in Italy around 1215; block printing arrived in Germany around 1370 and spread to Italy not too long after; the printing press came along in 1440; playing cards from the Mamluk caliphate came to Italy and Spain around 1370, as well; and from that point onward, card games spread rapidly throughout Europe. “Tarot made its appearance as soon as conditions allowed; it couldn’t have happened any earlier,” Smith concludes.

Early versions of the card decks that would later evolve into the tarot differed from the deck of 52 cards that became the basis for the standard decks of French-suited cards we use to play poker and such now, in that they had more than four suits. Those suits were there, of course; at the time, they consisted of cups, coins, swords, and batons (originally polo sticks in the Mamluk decks). But in the early 15th century in Italy, a fifth suit arrived: A “triumph” suit marked not by a common theme between the cards, but illustrated with lush scenes of animals, flowers, hunting, or allegories. (And if you know your tarot suits and you’re thinking, “Gee, that sounds an awful lot like the Major Arcana,” you’d be absolutely correct: The original four suits make up what we now call the Minor Arcana, while the triumph suit evolved into Major Arcana.)

The triumph suit arose out of trick-taking games, in which one of the original four suits could be designated as a triumph suit, thus giving them added power over the other three. (That is, playing a card from the triumph suit would eclipse any card from any other suit in the deck.) Decks that included a standalone triumph suit in addition to the other four suits therefore became known first as naibi a trionfi, then later as carte da trionfi — triumph cards.

The earliest known written reference to triumph cards occurs in the diary of Giusto Giusti, a notary and public official from Anghiari in Italy’s Tuscany region. Dated Sept. 16, 1440, the entry reads, “Venerdì a dì 16 settembre donai al magnifico signore messer Gismondo un paio di naibi a trionfi, che io avevo fatto fare a posta a Fiorenza con l’armi sua, belli, che mi costaro ducati quattro e mezzo” — or, in English per tarot researcher Ross Caldwell, “Friday 16 September, I gave to the magnificent lord sir Gismondo, a pack of triumph cards, that I had made expressly in Florence, with his arms, and beautifully done, which cost me four and a half ducats.”

(It’s worth noting here that although block printing and the printing press allowed for the relatively inexpensive mass production of decks of cards later on, early tarot decks were hand-painted and therefore not cheap — hence the four-and-a-half ducat price tag.)

By the early 16th century, though, the name of the cards began to change. In order to separate the five-suited deck from the four-suited ones used to play a game of Triumphs that was popular at the time, what were once known as carta da trionfi became known as Tarocho or Tarocchi — and when the cards spread to France, they first gained the name Taraux, then Tarot. But all that time, they were used to play games, rather than to divine the future — so how did we get from point A to point B? Unfortunately, that’s not entirely clear — there are huge gaps in the historical record, so much remains that we simply have no way of knowing — but we do have a rough idea of the timeline involved.

Written references to cartomancy more broadly — that is, the use of any kind of cards for divination purposes, not just tarot cards — occur sporadically in documents spanning from around 1450 through the early 1600s. What many consider to be the first reference to tarot divination specifically, meanwhile, occurs in 1527 in Italian poet Teofilo Folengo’s Chaos del Triperuno: In one episode within this work, four characters draw cards said to reveal their destinies, after which another character writes a sonnet for each card drawn and the person who drew it.

The 18th century, however, is when the connection between the tarot and cartomancy solidified, as well as when all the ideas of it being Egyptian in origin first emerged. While French clergyman Antoine Court de Gébelin was likely the first to write at length about the tarot’s supposed Egyptian origins and its divine significant — the eight volume of his 1781 work Le Monde primitif is a treatise on the tarot — tarot historian Michael Dummett pinpoints cartomancer Jean-Baptiste Alliette, also known as Etteilla, as the first to devise a full method of tarot divination and assign meaning to each card. Etteilla’s 1785 work, Manière de se récréer avec le jeu de cartes nommées Tarots (in English, How To Entertain Yourself With The Deck Of Cards Called Tarot) is essentially a how-to manual for reading tarot.

From there, tarot as a form of divination took off — and it’s kept on rolling ever since. From France to England to the United States, from the occult movements of the 19th and 20th centuries to more modern takes, and from Aleister Crowley’s Thoth Deck to A. E. Waite and Pamela Colman Smith’s Rider-Waite-Smith Deck, the tarot has proven that it’s here to stay.

Since this is all just meant to be a brief history of tarot cards (and it’s already over 1,000 words), I’m not going to cover these more recent periods in depth; for that, I’ll send you over to Sherryl E. Smith’s site, Tarot Heritage, and the history and research section of Mary K. Greer’s tarot site. These two resources are exhaustive with regards to the deep, deep history of cartomancy in general and tarot in particular, so have fun going on many, many deep dives, thanks to their work. Additionally, Michael Dummett’s work on the history of tarot is considered to be definitive; if you can get a hold of his 1980 book The Game Of Tarot: From Ferrera To Salt Lake City, it’s one of the be-all, end-all works on the subject.

So: What next?

Normally, this is where we’d jump into the two arguments about how tarot works — but since reading the tarot is a little more complicated than, say, using dowsing rods or what have you, I’m going to break with tradition here and include a section on how the cards are actually read. One of the most appealing qualities of the tarot is that there are so many ways to read the cards; either way, though, it’s important to have at least a general understanding of how the cards are traditionally used before we talk about how they work. So: Here are the nuts and bolts of tarot reading.

Reading The Tarot

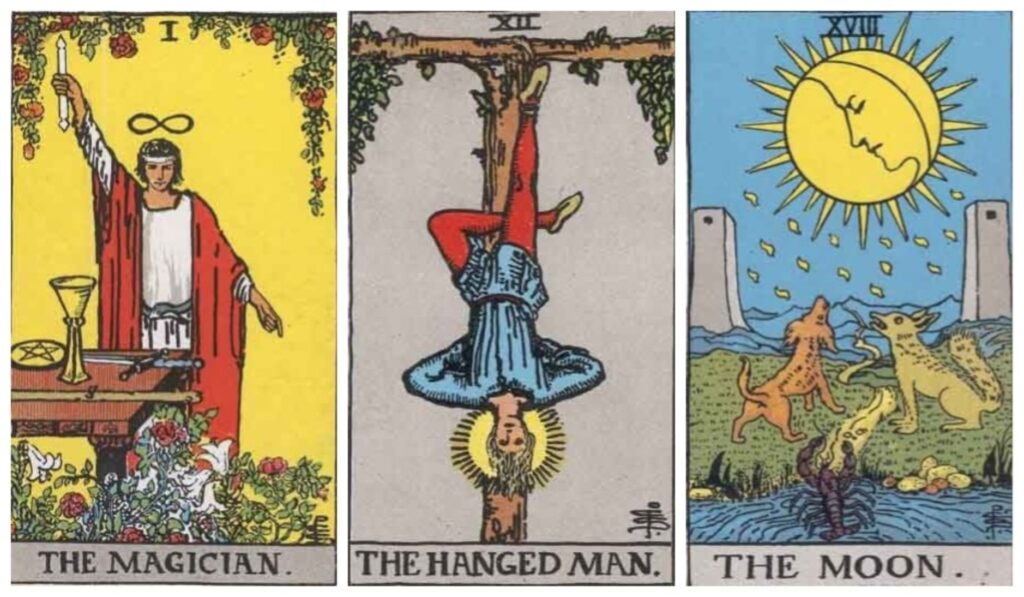

Tarot decks as we know them today generally have 78 cards divided into two groups, or arcana: The Major Arcana — a group of 22 suit-less cards depicting detailed, symbolic scenes; and the Minor Arcana — a group of 56 cards divided into four suits of 14 cards each depicting the mundanities of everyday life. The suits are usually comprised of Cups, Wands, Swords, and Pentacles or Coins. The Major Arcana may be numbered with Roman numerals in a few ways; commonly, the numbers run from 0 to XXI, although it’s not unheard of to see decks numbered from I to XXII, or from I to XXI with the final card completely unnumbered. In the Minor Arcana, meanwhile, each suit contains cards numbered from one to 10, plus four court cards represented by the King, the Queen, the Knight, and the Page. (The Page may also be known as the Jack or the Knave.)

Each card has a meaning, of course; the meanings are broad, though, and up for interpretation, rather than narrow and prescriptive. You’ll sometimes see the Major Arcana and each of the suits of the Minor Arcana described as representing specific areas of focus — for example, as Biddy Tarot puts it, the cards of the Major Arcana may be said to represent “life lessons, karmic influences, and the big archetypal themes that are influencing your life”; the suit of Cups, “your feelings, emotions, intuition, and creativity”; the suit of Coins or Pentacles, “your finances, work, and material possessions”; the suit of Swords, “your thoughts, words, and actions”; and the suit of Wands, “your energy, motivation, and passion” — but there are variations in how they’re each viewed, as well, depending on who you talk to.

Cards may be read according to their standard meanings or their inverted or reversed ones; exactly which reading you go with depends on how you draw the card. A card is considered to be inverted if it’s drawn or placed in the opposite manner it typically would be — for example, if it’s upside-down when you draw it. Reversed meanings aren’t necessarily bad — card meanings are usually a bit more subtle than simply “good” or “bad” — but depending on the card, they can represent things you might struggle with or negative influences that might be affecting you. (Then again, some cards’ reversed meanings are actually more positive than their regular ones, so, y’know, your mileage may vary and all that.)

And as for how you actually go about reading the cards? First, focus on what you want to know, whether it’s an answer to a specific question about your life or whether you’re looking for more of a general summation of what’s going on for you. Then, shuffle and deal out the cards in your spread of choice. You can adapt the ritual of the reading however you like, but those are the important things: Focus on the purpose of your reading, then shuffle and deal.

There are countless spreads to choose from, but if you want to start simple, a three-card spread should fit the bill.

A general three-card spread is usually drawn linearly — that is, you draw three cards and lay them out in the order in which you drew them in a line from left to right. These cards, in order, typically represent your past, your present, and your future — although exactly what each of those things mean can vary. Your past is typically about where you’ve been or what your situation or circumstances may have been. Your present is about where you’re at right now — your current situation, your thoughts and feelings, whatever you might be grappling with, that kind of thing. And your future? Well, it’s not necessarily a straight-up prediction of what awaits you later on down the line; it might have something more to do with the future’s potential, or with your aspirations for the future, or your desired outcome.

I say “typically,” though, because there are numerous ways to interpret this spread. You can read three-card spreads for specific situations or areas of focus — say, for career-related queries, for love and relationships, or for self-discovery. You can even lay them out differently, foregoing the linear draw — which might then change how you interpret each card: They might represent your mind, your body, and your spirit; they might represent your strengths, your weaknesses, and guidance on moving forward; and so on and so forth.

If you’re up for something more complicated, there’s the Celtic cross spread. A 10-card spread, the Celtic cross consists of two parts: The cross itself, which is positioned on the left, and the staff, which is positioned on the right. The cards in the cross typically represent the querent’s present situation, the challenges they’re facing, what’s in their past, what might be in their future, their aspirations, and any underlying feelings they might have. The cards in the staff, meanwhile, usually represent advice for the querent’s current situation, what external forces or influences might be at play, the querent’s hopes and fears, and the possible outcome of the situation. Again, I say “typically” and “usually” because there are lots of variations on this spread out there; your mileage may vary based on which one you choose.

If you like, you can choose what’s called a significator card as part of your reading. This card is meant to represent the person whom the reading is focused. It can be consciously chosen before the reading begins or drawn at random as the first card in a spread.

If consciously chosen in advance, it’s common for the significator card to be drawn from the court cards of the Minor Arcana, often according to age, gender identity, physical appearance, or astrological sign. (For example, the Page might be used to represent a child, while the Queen or King might be used to represent an older adult; meanwhile, the suit of Cups might be used to represent a Pisces, Cancer, or Scorpio — that is, the water signs — while the suit of Pentacles or Coins might be used for Earth signs like Taurus, Virgo, and Capricorn.) However, a consciously-chosen significator card can be drawn from anywhere in the deck — for example, if the querant or focus of the reading is a couple, you might use the Lovers from the Major Arcana; or, if your query is coming from a place of anxiety or worry, you might chose the Nine of Swords.

Even if you don’t consciously choose a significator card before you begin, some spreads actually include one in the generally layout — for example, the first card drawn in a Celtic cross spread usually functions as a significator card. You can also use a separate significator card with this spread, too, though.

Not all readings require a significator card; it’s not only possible, but common to perform readings without one. Whether you use one usually comes down to either the spread itself, or simply to personal preference.

So: How does it all work? What’s the mechanism by which tarot cards fulfill their function — whether you believe in them or not? Let’s take a look.

The Believer’s Argument

As is the case with a lot of forms of divination (and ghost hunting techniques, and other things of this ilk), there isn’t really a general consensus among believers on exactly why the tarot works. However, the debate is also a little bit different with tarot than it is with, say, spirit boxes or talking boards — largely because not all of the explanations have a belief of the supernatural at their center.

According to some — particularly those who follow in the tradition of the French, English, or American occult tarot — yes, there’s some sort of mysticism involved in the reading of tarot.

As Mike Sosteric puts it in the article “A Sociology of Tarot,” published in the Canadian Journal of Sociology in 2014, the “early days of tarot mysticism” held that the cards “could provide a gateway or a channel that would facilitate communion with jinn, angels, and other exalted heavenly hosts”; meanwhile, in the more modern era, tarot — and divination more generally — is often presented as “an attempt to explain the world where science seems unable to work” or “as a tool for developing the inner eye.”

No one really knows how these “gateways” or “channels” work; there are theories, but nothing has been definitively proven. Still, though, for those who believe in realms beyond our earthly plane, that’s where the key lies: The cards open a sort of conduit to these other realms and allow us to access information we might not otherwise be able to see.

For others, though, the cards open a conduit not to something supernatural, but to our own inner workings — that is, they’re more like a form of meditation, or a tool to aid in sorting through your own thoughts. As one tarot card reader told James McConnachie writing for Aeon 2017, a reading is more often about “tuning into [your] gut instincts” than predicting the future. Said the reader, “The future is not set in stone. You have options, and sometimes what a reading is about is helping you to see those options.”

Katie Robinson, who reads tarot under the name Maisy Bristol (on social media, Tarot By Maisy), put it this way in an essay for Marie Claire published in 2017:

“Nobody comes into a reading expecting a cut and dry answer, or for God to bestow them with the gift of sight and Labrador puppies. What they really crave is either 1) subconscious insight or 2) for the reading to match what they already believe to be true.

It’s like this: Sometimes our conscious minds know what we are hoping to hear; other times they aren’t aware of what they need to hear. … Tarot spreads simply create an opening for this insight. They are a visual map of our minds, as I like to say, and tarot readers are the key.”

Or, in the words of one Redditor posting in the r/Tarot subreddit in 2018:

“There is no meaning in the cards themselves. The meaning is all inside the interpreter’s head. It really does not matter which cards one chooses, but any card can serve as a starting point to discovering insight that is already there deep inside my mind … I [just] did not realize consciously it was there before. Tarot cards work like those ink splotches psychologists use to reveal one’s subconscious insights.”

“Those ink splotches” are Rorschach test images. The Rorschach test has been controversial with regards to its validity since its inception (psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Hermann Rorschach created it in 1921), but some — including the researchers behind a study published by the American Psychological Association in 2013 — maintain that it’s more useful than it’s often thought to be these days. As Damion Searls, author of a biography of Rorschach called The Inkblots, put to National Geographic in 2017 (emphasis mine), “People don’t understand it’s about how you see, not what you see.”

As that one Redditor points out, the same could also be said of tarot cards: Reading the cards isn’t necessarily about the cards themselves. It’s about how you see them — and how you relate them to your own situation and self.

In any event, the bottom line is this: Pretty much everyone who believes in tarot has their own interpretation or idea about how it works. They might not agree on the mechanism itself, but they do all agree that no matter what that mechanism might be, it’s not actually the important thing about the cards. The important thing is that they work at all.

The Skeptic’s Argument

Skeptics, however, tend to view tarot with a much more cynical eye: For those who don’t believe in the power of the cards, a tarot card reading is nothing more than some skilled cold reading skills paired with a sense of storytelling.

For those well-versed in cold reading, it’s easy to learn huge amounts of information about strangers in an incredibly brief period of time — all without your target knowing that they’re giving up everything to the cold reader all on their own. The key lies in a set of techniques that exploit one of humanity’s natural psychological quirks combined with powerful observation skills.

The quirk I’m talking about here is called the Forer effect. In 1948, psychologist Bertram R. Forer found that, when he gave 39 of his students a test and told them that they’d each receive a brief profile of their own personalities based on their results, they all rated their profiles as extremely accurate. But there was a catch, of course: The students all received the same profile, which Forer had drawn from an astrology book he acquired from a newsstand. This experiment cemented the Forer effect: A psychological phenomenon in which people who are given personality descriptions which are actually vague enough to apply to huge swathes of the population rate those descriptions as highly accurate when they’ve been convinced that they were personalized just for them. This effect is sometimes also called the Barnum effect, for noted hoaxer P.T. Barnum; the statements used in the personality descriptions are referred to as Barnum statements.

The cold reader’s toolkit is wide and varied, but the Forer effect is at the center of most of the techniques used. Cold readers might, for example, employ something called “shotgunning” — that is, throwing out a number of vague statements, seeing which ones their target picks up on or responds to, and running with them. This technique can be used to coax information out of a target, as well — that is, if the cold reader sees the target respond to one statement in particular, they can ask leading questions or otherwise prompt the target into revealing information about themselves in a way that makes it appears if the reader has divined it from on high. Even just good old-fashioned observational skills can come into play; you can tell a lot about someone from how they present themselves, from their appearance down to their behavior.

Most of the time, you probably think of cold reading in terms of television psychics like John Edward — just a lone person on a stage, throwing out vague Barnum statements until an audience member latches onto one of them. It’s functionally the same with tarot cards, though. I would argue that tarot is a little more structured, due to the way the spreads work — that is, a good cold reader can use the role each card is meant to play as a springboard for implementing one or more of the techniques described above, rather than simply running at the mouth until something sticks — but at bottom, there’s isn’t much difference between the way a general psychic operates and the way a tarot card reader operates.

Cold reading isn’t always carried out maliciously or with an intent to defraud; indeed, as Karla McLaren, a former psychic healer who changed tack in 2003 and became a researcher in the social sciences, noted in 2004, some people who are actually quite skilled in it don’t necessarily know that’s what they’re doing. Wrote McLaren for the Skeptical Inquirer, “I never knew what cold reading was, and until I saw professional magician and debunker Mark Edward use cold reading on ABC News special last year, I didn’t understand that I had long used a form of cold reading in my own work!” She continued, “I was never taught cold reading and I never intended to defraud anyone — I simply picked up the technique through cultural osmosis.”

And, of course, you also have to be a good storyteller to be a good tarot card reader. Most tarot spreads have the structure of the story literally laid out for you: There’s a protagonist, a challenge the protagonist is trying to overcome, a backstory, their hopes and dreams — all you have to do is draw it together into a compelling narrative based on the clues you’ve picked up through your cold reading.

To be fair, the storytelling aspect of tarot is important for those who believe in it, as well; that’s where the true value of the interpretation work emerges from. Indeed, most resources geared towards teaching tarot reading include sections on storytelling — the story draws the meanings of the cards together and helps paint a fuller picture. But for skeptics, the storytelling serves a different purpose: It plays off of the Forer effect, making a seemingly personalized story out of the cards — and thereby making it more likely that querents will believe in the accuracy of the reading.

I suppose the lesson here is, never underestimate our ability to make everything about ourselves. Cynical? Maybe. True? Probably.

What Do You Believe?

The thing that I find most interesting about tarot cards is the fact that all of these possibilities can simultaneously be true:

Yes, there are people who use the cards in a way they believe allows them to access the supernatural.

Yes, there are people who use the cards in a way they believe allows them to access their true thoughts and feelings about a given situation.

Yes, there are people who use the cards to trick or con unsuspecting marks.

And yes, all of these types of people likely use cold reading skills in one way or another, even if they aren’t aware that they’re doing it.

I don’t know if they always are simultaneously true; however, they’re not mutually exclusive, and that’s interesting to me.

As for myself? Back during my own tarot card reading days, it was less about the mysticism and more about organizing my thoughts. (Also, it was fun.) Even now, I’m inclined to think that they do, in some regards, “work” — just not as gateways to supernatural realms. The way I see it, using tarot cards to figure out how to proceed in a given situation is similar to journaling or freewriting: The act of reading facilitates self-reflection and self-discovery by engaging you in outside-the-box thinking.

In that case, are the cards sort of a self-fulfilling prophecy? Do you find meaning in them because you think you should? Do you find the meaning you’re actively looking for? Are you using them to confirm something you already know? Yes, yes, yes, and yes. But that’s not necessarily a bad thing. The cards allow you to speak honestly with yourself — to tell yourself what you know, deep down, you need to hear.

And that, I think, is quite valuable, indeed.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via Elenath_ithil, Erdenebayar/Pixabay; Wikimedia Commons (1, 2, 3, 4), available via the public domain or a CC BY-SA 4.0 Creative Commons license; Jen Theodore (1, 2)/Unsplash]

Leave a Reply