Previously: The Forest Grove Sound.

The story goes something like this:

In June of 1947, the Dutch vessel S.S. Ourang Medan was reportedly navigating the Marshall Islands in the Micronesian region of the Pacific Ocean when it sent out an unsettling transmission: “S.O.S. from Ourang Medan,” read the message when deciphered from the Morse code in which it had been sent. “We float. All officers including the captain are dead, lying in the chartroom and on the bridge. Possibly whole crew dead.” A handful of garbled dots and dashes came through next; then two more complete words followed: “I die.”

And after that… nothing.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

Several ships in the area picked up the Ourang Medan’s message, including two from the United States, the S.S. City of Baltimore and the S.S. Silver Star. Both of these vessels were several hundred nautical miles away from coordinates transmitted by the distressed ship, but they both attempted to continue engaging the Ourang Medan while the closer of the two — the Silver Star — changed course. No further transmissions came from the ship, however, and when the Ourang Medan was finally located, silence greeted the Silver Star. The ship, drifting gently and listing slightly to starboard, did not respond to a siren call. It did not respond to being hailed with a megaphone. And when the crew of the Silver Star boarded, it quickly became apparent why.

They found the first bodies on the upper decks.

Spread out on their backs, their upward-turned faces frozen in fear, the crew of the Ourang Medan had clearly suffered something unimaginably horrible. The Silver Star’s crew found more of the same on the bridge, in the wheelhouse, and chartroom—officers, the captain, the radio operator… every single soul aboard the ship had expired. Not even the ship’s resident dog had escaped whatever terrible fate had befallen the Ourang Medan.

The crew of the Silver Star observed that one lifeboat was missing — but before they could investigate further, the scent of smoke drifted up to them. Knowing what such a sign meant, they quickly vacated then vessel and returned to their own. Moments later, a vast explosion sounded. The Ourang Medan went up in flames, burning brightly and terribly before sinking beneath the waves.

Was it a curse? An accident? An encounter with something as yet unknown? It’s never been solved. To this day, no one knows what happened aboard that vessel.

But, even more oddly, to this day, no one knows whether or not the vessel even existed in the first place.

The ship pictured above is not the S.S. Ourang Medan, by the way. It’s the S.S. Marine Jumper, a Type C4-class cargo ship which was in service in the United States between 1945 and 1952. For some reason, this image has become heavily associated with the Ourang Medan, although I’m unclear how or why that association began.

But true or not, the tale of the Ourang Medan has become fixed in the landscape of maritime legend; indeed, it has proven to be so persistent that it’s even made its way into the CIA archives: A letter written to the Director of the CIA’s assistant by one C. H. Marck, Jr. in December of 1959 and now publicly available via the CIA’s online reading room describes one of the most commonly recounted versions of the story. The letter’s writer was “sure that the S.S. Ourang Medan tragedy holds the answer” to the many “unsolved mysteries of the sea” that can be found wending their way throughout history.

Can it? Really? Well… you’ll have to make up your own mind about that.

For many years, the earliest mention of the Ourang Medan in print was believed to be a series of articles published by the Dutch newspaper De Locomotief between early February and mid-March, 1948. The first of these articles hit print on Feb. 2; the second on Feb. 28; and the third on March 13. From these articles, we get the main points of the story — the distress call, the discovery, the explosion, the sinking of the ship — as well as the key details of the date and place at which the events are said to have occurred: June 1947, near the Marshall Islands.

The source for the stories in De Locotmotief, however, is somewhat roundabout: All the information came via a man named Silvio Scherli of Trieste, Italy, who said that he had heard the story from a missionary, who had himself been told the tale by a surviving sailor from the Ourang Medan. The sailor had allegedly washed up on the Taongi atoll, imparted his story to the missionary, and then died. Already, we’re dealing with a framework familiar to anyone who knows their urban legends: We’re not hearing the story from a first-hand source; we’re hearing it from a(n alleged) source three or four steps removed.

And if you go digging for other news coverage, you’ll find something even more curious: Although the arc of the story is always the same, the details differ dramatically from piece to piece.

For example, in an article titled “Secrets Of The Sea” by Win Brooks, which seems to have been published in syndication in October of 1948, the location of the event has changed: The ship’s discovery is placed in the Strait of Malacca, which passes between Peninsular Malaysia and the Indonesian island of Sumatra. Meanwhile, in the Proceedings Of The Merchant Marine Council, a publication of the U.S. Coast Guard, an article dated May 9, 1952 titled “We Sail Together” recounts the story of the Ourang Medan as having occurred not in June of 1947, but in February of 1948.

These changes from story to story are already enough to suggest that we might be dealing with something that’s more legend than history — but a discovery made by Estelle Hargraves of the Skittish Library in 2015 offers even more compelling evidence to that point: Accounts of the allegedly missing ship appear in several British newspapers in 1940 — years before the whole thing is meant to have occurred in the first place.

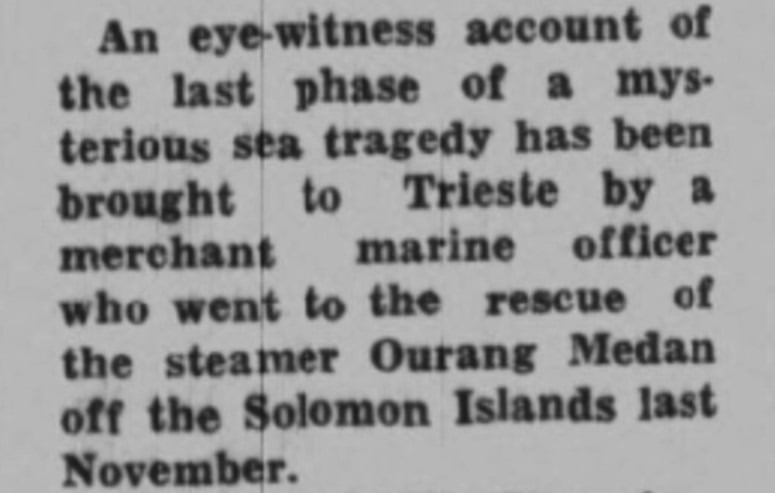

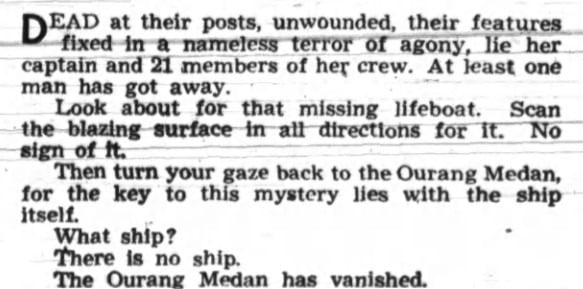

As Hargraves points out, the Yorkshire Evening Post and the Daily Mirror both contain articles dated November of 1940 describing the plight of the Ourang Medan. (I also found an additional article from the Hampshire Telegraph that fits within this cluster of coverage, as well.) These articles feature the now-familiar shape of distress call, discovery, explosion, sinking; however, they place the incident in yet another location: The Solomon Islands in the Melanesian region of the Pacific Ocean.

Also, like the articles in De Locomotief, one of the articles from 1940 — the one in the Yorkshire Evening Post, which is credited to the illustrious Associated Press — reportedly comes from an eye-witness arriving in Trieste, Italy. However, in this case, the witness isn’t a surviving crew member of the Ourang Medan itself, but rather an officer from the vessel that attempted to rescue it — a vessel which, by the way, is unnamed (no Silver Star here). The details of the deaths in this article are less gruesome than those in the De Locomoteif pieces, as well, with the officer remarking only that it looked as if “death seemed to have taken [the sailors] by surprise at their posts.”

But here, the plot thickens again. Building off of Hargraves’ work, Andrew Hochheimer took a dive into the Ourang Medan — and one of his sources, Alexander Butzige of the book The Ourang Medan: Conjuring A Ghost Ship, seems to have located a news article that pegs a precise date to the mystery. According to Butzige, who also wrote about his find in a post on Goodreads, an article in the French magazine Sept-Jours dated Sept. 7, 1941 titled “Après Vingt Mois — Le Mystère de l’ ‘Ourang-Medan’ Est Éclairci” not only claims to have solved the mystery (indeed, the title translates to “After 20 Months, The Mystery Of The Ourang Medan is Solved”; more on that in a bit), but also references an article in an earlier issue dated Dec. 29, 1940. And according to both of these articles, via Butzige, the Ourang Medan incident is reported to have occurred on Nov. 13, 1939.

It’s perhaps worth noting that reviews for Butzige’s book are mixed; what’s more, I haven’t myself seen the articles he references, so I can’t vouch for them as sources. But the information, if true, does complicate the story even more, which makes it all the more fascinating.

Because, yes, as Butzige describes it, there are more details in the French version of the story that differ, as well. For example, the ship that finds the Ourang Medan in the Sept-Jours articles apparently isn’t called the Silver Star; it’s not even named at all, instead identified merely as an American torpilleur, or torpedo boat. The events are placed around Fiji, in Melanesia. And lastly, the Ourang Medan isn’t described as a Dutch vessel, but rather one owned by the Australian government which had previously transported prisoners to penal islands and later been sold to a smuggler.

So many details. So many divergences. What are we to make of them?

Did the alleged incident happen in 1939? 1940? 1947? Or 1948?

Did it happen near the Marshall Islands? Near Malaysia? Or near the Solomon Islands?

And what of the major players in the alleged incident? The Silver Star, for example, is a particular problem in the mystery of the Ourang Medan. As Butzige points out, it makes sense that the vessel that locates the Ourang Medan in the French articles isn’t the Silver Star: Records show that not only was this ship not even built until 1942 — meaning it couldn’t possibly have gone to the Ourang Medan’s rescue in either 1939 or 1940 — but moreover, it had a different name entirely until 1946. In its first few years, the ship was named the Santa Cecilia. It became the Silver Star in 1946, but only for a single year; it was renamed again in 1947, this time becoming the Santa Juana, before ultimately being scrapped in 1971.

It also makes sense that the British articles from 1940 don’t include mention of the Silver Star; it didn’t exist yet. So how did it become part of the story later on? And, knowing that it does become tied up with the Ourang Medan, if the incident had, in fact, happened, how could the Silver Star have been the ship to have found the Ourang Medan adrift in 1947 or 1948 if it had taken on a different name in 1946?

And where does Silvio Scherli fit into the picture? He’s mentioned by name only the De Locomotief articles, but his hometown of Trieste appears in the British articles from 1940 — a connection that seems to specific to be mere coincidence. Could Scherli have come up with the story himself, as Estelle Hargraves of the Skittish Library theorizes? And if so, to what end? For mere notoriety — an early version of the desire to seize your own 14 minutes of fame and go viral?

What’s more, as marine historian Roy Bainton found in his investigation of the Ourang Medan in the September 1999 issue of the Fortean Times, there is also no record of the case in Lloyd’s Shipping Registers, nor any record of the Ourang Medan itself in Dutch shipping records. What are we to do with that information? Can we safely take that as proof that the Ourang Medan never even existed, let alone went up in flames after its crew’s sudden demise?

We have many questions, but very few answers.

It’s worth noting that there is one version of the story which solves many of these discrepancies, and explains what killed the crew and set fire to the ship — although it, too, brings up numerous questions, as well.

Remember when I said that we would get back to exactly how the Sept-Jours article solved the mystery, according to its own claims, per Alexander Butizige?

That’s the version we’re talking about here.

According to Butzige, the story recounted in the Sept-Jours articles came from a man who had washed up on Viti Levu, the largest island in the chain that makes up Fiji — a man who, at the order of Harry Luke, the British colonist who served as governor of Fiji between September of 1938 and July of 1942, was brought to the government’s offices and interrogated about the ship from which he had escaped: The Orang Medan.

The captain and officers of the Ourang Medan were Europeans, said the man, while the sailors were Pacific Islanders who were frequently mistreated by their commanding officers. With these contentious relationships in place, the ship loaded up its cargo in Singapore in October of 1939: 2,500 crates, each sealed, their contents unknown to the sailors.

They set out for Sydney — but after just a few days at sea, the ship’s destination changed. They were now bound for Panama, a much longer journey that worried the sailors.

But worry soon turned to fear as people started dying, dropping dead with seemingly no cause.

The sailors mutinied. The radio operator sent out a distress call. An unnamed vessel answered it. Two life boats escaped from the distressed ship — but only one survived, with just one passenger making it to safety. And at some point, the Ourang Medan burst into flames.

That one passenger, of course, was the man forced to tell his story to the colonial government of Fiji.

Eventually, an investigation was launched — and that’s when it was discovered that the ship’s cargo was to blame for both the deaths of those aboard and the explosion that took down the ship. The crates carried improperly stored nitroglycerine, potassium cyanide, and sulfuric acid, which reacted to create a toxic gas which slowly spread through the ship via the ventilation system. When the ventilation fan stopped working, the gas ignited, and — boom.

If the Ourang Medan was a smuggler’s ship originally based in Australia or working out of Singapore, it wouldn’t have been in the Dutch records. It also would have done everything possible to escape documentation and slip under the radar. And, again, there is notably no mention of the Silver Star here, which is consistent with the historical record of that particular ship.

But is this story really true? Or is it, too, a fabrication — possibly one dating as far back as the 1930s? And in either case, is this story — fact or fiction — responsible for the legend that exists today? Did it morph and twist over time, becoming a story not of smuggling and human cruelty, but one of a cursed vessel — a ghost ship?

For now, the mystery remains — and as long as it remains, it will continue to fascinate. It has been the subject of numerous pieces of writing; it has appeared in podcasts; it has even served as the inspiration for a survival horror game: Man Of Medan, the first installment of the Dark Pictures Anthology series.

Would you like to get lost aboard the Ourang Medan? You can try your hand at it in Man Of Medan.

Oh, and while we’re on the subject, that’s actually what Ourang Medan translates to: Man of Medan. It’s from the obsolete Malay word for “man” — ourang, or orang — and the city of Medan, the capital of North Sumatra.

Does that change your understanding of the ship?

Of where it came from, or where it might have been going?

Maybe.

Maybe not.

But it’s interesting all the same.

Don’t you think?

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

Leave a Reply