Previously: The Black Paintings of Francisco de Goya.

In 1678, a curious pamphlet, printed and published quarto-style via woodblock, appeared in England, coming out of Hertfordshire in the southeast. Titled “The Mowing-Devil: Or, Strange News out of Hartford-shire,” it recounted a curious incident — one in which a farmer, annoyed at the price quoted to him by a mower for his services, vis-à-vis cutting down three half acres of oats, swore he’d rather have the Devil mow his field instead. The farmer was shocked to find his field on fire that night — but even more shocked to find the next morning that his crop had been neatly cut.

He believed the Devil had, in fact, come to mow his field. Accordingly, he refused to harvest the oats — and presumably learned his lesson about being a miser.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

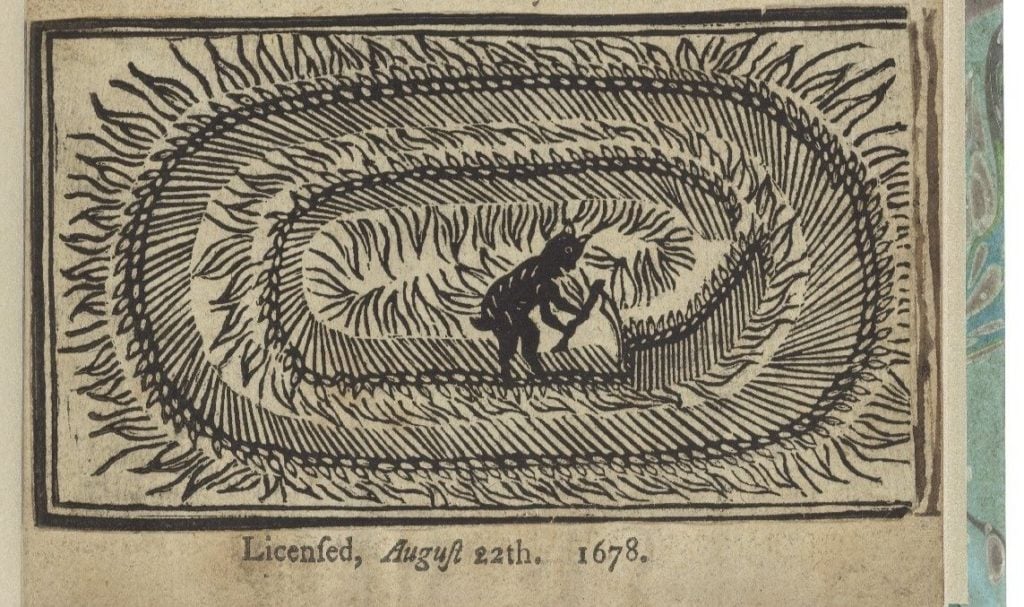

The Wikipedia page on the Mowing Devil pamphlet is scant, if creepy; if you start digging based on what little information the page has, though, you’ll find a wealth of knowledge — and even more speculation about what exactly might have been going on there. The biggest debate centers around whether or not the incident is an early example of a crop circle. Those who argue that it is cite an illustration included on the pamphlet’s cover page as clear evidence that the farmer found not a field mowed by the Devil, but a field that had been marked with a crop circle; however, those who argue that it isn’t note that the field’s crop was cut, rather than pressed.

And that’s before we even get into the debate of whether crop circles are evidence of extraterrestrial life landing on Earth or whether they’re just largescale art projects similar to corn mazes.

For the curious, a transcription of the pamphlet’s cover page — the page on which the crop circle-esque illustration appears — reads as follows:

“Being a True Relation of a Farmer, who Bargaining with a Poor Mower, about the Cutting down Three Half Acres of Oats; upon the Mower’s asking too much, the Farmer swore That the Devil should Mow it rather than He: And so it fell out, that very Night, the Crop of Oats shew’d as if it had been all of a flame; but next Morning appear’d so neatly Mow’d by the Devil, or some Infernal Spirit, that no Mortal Man was able to do the like.

Also, How the said Oats ly now in the Field, and the Owner has not Power to fetch them away.”

For what it’s worth, crop circles these are largely considered to be human-made — all you need to make one is a field sown with a crop like wheat or barely, a wooden board, a piece of rope, and some creativity and perseverance. Still, though, there are plenty of folks who believe crop circles are UFO-related or otherwise paranormal in nature.

It’s not currently known what happened to the wood carving itself; however, three original prints exist, two of which are in the United States and one of which is in the UK.

We may never really know what happened to that farmer in 1678 — but I hope he learned to pay people what their work is actually worth.

Further Reading:

The Mowing Devil at the LUNA: Folger Digital Image Collection. A digitized version of a copy of the pamphlet’s cover page is available online courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC. According to the manuscript’s holdings notes, the “outer edge of [the] woodcut mounted on [the] title page [is] slightly cropped, with [the] border drawn in with brown ink.” The manuscript is “quarter bound in modern mottled calf with marbled paper boards,” and has “gold-tooling on [the] spine, gold fillets on [the] boards, [and a] gold title on [a] black leather spine label.” The “binder’s ticket” is “anonymous.” You can zoom really far in on it, so if you want to see the page in all of its glorious detail, click through.

1678 – Hertfordshire: “The Mowing Devil” at Old Crop Circles. The website Old Crop Circles is rudimentary in appearance; however, what it lacks in pizzazz it makes up for in uniqueness of content. Run by Terry Wilson, who has also self-published a book on the subject, it’s dedicated to documented crop circles that appeared prior to 1978.

Wilson is very much a believer, so if you’re more of a skeptic (e.g., if you’re like me and you’re pretty sure that most crop circles are just creative designs stomp out in fields of wheat by humans with pieces of wood and too much time on their hands), you may not agree with Wilson’s POV; he does, however, have the best collection of early instances of possible crop circles I’ve found. The page on the Mowing Devil pamphlet is of particular interest due to its measured treatment of the arguments both for and against it as a crop circle. Some might consider it semantics, but the semantics, it turns out, matter quite a lot.

The Mowing Devil at UFOs At Close Sight (including complete Mowing Devil pamphlet transcript). Run by Patrick Gross, UFOs At Close Site contains nearly 20 years of ufology — cases, theories, questions, the works. The section on crop circle is expansive, of course — the entire site is expansive — and contains a particularly detailed article on the Mowing Devil pamphlet, much of which is devoted to addressing the ongoing debate around whether or not the story told in the pamphlet really does depict a crop circle or not. However you feel about that debate, though, Gross’ article is also notable for another reason: It contains a full transcript of the complete pamphlet — not just the cover page. It’s around 1,000 words and details the entire event as it was said to have occurred on Aug. 22, 1678.

The Mowing Devil at Early Modern Pamphlets. Run by science historian Darin Hayton, who chairs the history department at Haverford College, Early Modern Pamphlets is “a collection of pamphlets that treat cases of witchcraft or possession” from the early modern period of history — that is, the period spanning from around the 16th century through to the French Revolution in 1789. Per its About page, it was originally intended as a teaching aid (hence its bare bones appearance); it’s since grown into a solid, publicly available resource concerning pamphlets not just on witchcraft and possession, but also on meteorological phenomena (think comets, hail, thunder, etc.).

If you have trouble with the kind of language in which primary sources like the Mowing Devil pamphlet are written, Early Modern Pamphlets is great resource; it explains exactly what these sources are saying, translating particularly difficult sentences and phrasing into modern English. The page on the Mowing Devil pamphlet both summarizes the details of the story contained within the pamphlet and comments on its form and structure: That is, it’s a “dramatic narrative, relaying the story after the matter” with a specific point of view (e.g. the farmer was unreasonable) that has a firm belief in God, the Devil, and the concepts of heaven and hell.

The Devil And Demonism In Early Modern England by Nathan Johnstone. Part of the Cambridge Studies In Early Modern British History series, Johnstone’s book “examines the concept of the Devil in English culture between the Reformation and the end of the English Civil War” — and since the Mowing Devil incident occurred immediately following that period, this book does a terrific job painting a picture of the wider context surrounding both the pamphlet itself and the story within it. It’s readable for free at the link, too.

An Overview of Crop Circles at LiveScience. Let’s back up for a moment: What the heck is a crop circle, anyway? This article at Live Science explains the phenomenon, walking us through both early examples (like the Mowing Devil incident) and more modern examples (e.g. those dating back to the 1990s), describing the characteristics of your average crop circle, and explaining the many theories out there accounting for crop circles’ possible origins. Bonus: This piece was written by Benjamin Radford, who you might recall from the Wrinkles the Clown documentary.

“Crop Circles Demystified: How The Patterns Are Created,” by Louis Jani and Richard Gray. In 2013, the Telegraph published what’s essentially a how-to for creating crop circles. There are, to be fair, many a how-to guide out there, many of which are more detailed than the Telegraph’s; what I like about this one, though, is that it goes through not just all the things you’d expect it go through — choosing the right field (the crop itself matters, for example; heat, barley and rapeseed tend to work best), measuring out your design, creating and using a “stalk stomper” from a board of wood and rope, etc. — but also addresses how to go about the whole thing ethically. The piece points out how the damage caused by creating crop circles affects the farmers in whose fields the circles appear; the lost crops can result in hefty losses of revenue. As a result, notes the piece, crop artists typically obtain permission from the farmers who own the fields in which they make their circles, rather than just going ahead and destroying the crops without the farmers’ go-ahead. So, if you yourself want to make a crop circle, you should also refrain from doing so unless you’ve got permission from the owner of the field in which you plan to do it. Because, y’know, that’s the right thing to do.

“Creating Crop Circles With Lasers and Microwaves” by Rebecca Boyle. Fun fact: Although wooden boards with ropes have hitherto been the primary way of making crop circles, it’s not the only way to make them — not anymore. Over at Popular Science, Rebecca Boyle interviews Richard Taylor, physicist (and head of the University of Oregon’s physics department), on how technology might be changing the way circlemakers, as he calls them, do their work. He’s got an interesting perspective; he sees the fun and whimsy in the whole topic, while still applying rigorous scientific thought to it. As he puts it himself: “Although it’s an odd topic, it actually is quite rigorous science — here’s a mystery, here is a potential hypothesis that would solve this. It’s a perfect example of seeing something out there in the real world and using science to explain it. It’s just a little bit more exotic.”

“The Mowing Devil” by Simon Barron. Formerly one half of the folk duo Barron Brady, songwriter and musician Simon Barron released this delightful little tune on Soundcloud in 2016 — and it’s, uh, my new favorite song. There’s something about the combination of a calm, peaceful-sounding acoustic guitar and vocals track and lyrics about making crop circles that I find absolutely hilarious. It’s a beautiful song, but the lyrics are what really

For the curious, the “all across the papers in summer ‘91” line refers to a space of time in 1991 when crop circles began popping up with a startling degree of frequency across southern England. In September of that year, two “jovial con men in their 60s” stepped forward to claim responsibility for the circles. More in this article from the New York Times, which was published on Sept. 10, 1991.

A Field Full Of Secrets, dir. Charles Maxwell (2014). Independently produced and made available via VOD by Gravitas Ventures in 2014, this crop circle documentary is surprisingly balanced; the filmmakers are absolutely believers — indeed, that’s the premise of their exploration: They’re convinced that crop circles might actually be three-dimensional blueprints squashed into one dimension. But they do a solid job making sure their speaking to experts and authorities on both sides of the aisle, so to speak, making for an engaging look at a complex subject. It’s available to watch for free at Tubi.

Signs, dir. M. Night Shyamalan (2002). I mean, we couldn’t very well examine a crop circle-adjacent subject and not give Signs another look, could we? Despite M. Night Shyamalan’s failings as a filmmaker, it’s actually quite an effective film; indeed, in recent years, it’s been getting a lot of reconsideration from folks who had long written it off as simply yet another gimmicky plot twist from a one-trick pony. For what it’s worth, though, when it was first released, I saw signs immediately after driving through days of deserted Pennsylvania cornfields, and, uh… it was… not bad, in my view. It’s currently available on HBO Go, as well as rentable for a few bucks via Amazon Prime, Vudu, and a few other services.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Image via the public domain.]

Leave a Reply