Previously: The Lighthouse Keepers Of Eilean Mor.

It began with a kidnapping.

In 1984, Katsuhisa Ezaki had been the president and CEO of Ezaki Glico — the Japanese food and confectionery company perhaps best known for creating the chocolate-covered, twig-like biscuits called Pocky — for two years. But he had no idea that 1984 would turn out to be such a tempestuous year for the company… and he certainly didn’t expect the events that transpired in March to occur. Who would? After all, most people aren’t able to anticipate their own abduction — let alone an abduction at the hands of an anonymous entity known only as the Monster With 21 Faces.

But on March 18, 1984, the kidnapping occurred — and soon after, it would prove to be the first of a year and a half’s worth of odd, unusual, and downright sinister incidents targeting not just Glico, but a number of other industrial confectioneries in Japan, as well, including Morinaga, makers of the fruit-flavored, taffy-like candy Hi-Chew. For that reason, it’s widely known as the Glico-Morinaga case, rather than by its official case number, Metropolitan Designated Case 114. But usually, it’s referred to neither by its case number nor as the Glico-Morinaga case. Most people know it by the name of the person or group who perpetrated it: The Monster With 21 Faces.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now!]

We still don’t know who the Monster With 21 Faces really was. None of the crimes associated with the case were ever solved — and now that we’re well outside the statute of limitations for all of them, it’s unlikely that we’ll ever find out who was actually behind the whole thing.

The evening of March 18, 1984, Ezaki and his family were at home in Nishinomiya, about 17 kilometers outside Kobe, when several masked, armed men broke into their house. The intruders had actually started next door, where Ezaki’s mother lived; after overpowering the older woman and tying her up, they had retrieved the key for Ezaki’s house and moved onto their main target. The three men cut the phone lines, tied up Ezaki’s wife and children, and dragged Ezaki out of the bath and out the door. They brought him to a warehouse in Ibaraki, some 30 kilometers away from Nishinomiya and about 20 miles outside Osaka, where Glico’s headquarters are located.

The kidnappers demanded a ransom of 100 kilograms of gold bullion or one billion yen in cash for Ezaki’s — the equivalent at the time of about 220 pounds of gold bullion or $4.3 million USD — but three days after his initial abduction and before the police had many any significant inroads to the case, Ezaki escaped his captors on his own steam. He told police that he was able to loosen the ropes with which he’d been tied and kick down a door, escaping into the streets, according to news coverage at the time; after he broke free, he hailed down two railway employees for help, who aided him in phoning both the police and his family.

But life didn’t return to normal after Ezaki’s escape in 1984; indeed, things just got weirder. Soon after the Glico president’s return, letters began arriving — letters addressed to the police, to Glico, to other companies, and to newspapers and other media organizations — claiming to have been sent by the kidnappers. More than 100 of these letters, would emerge over the next year and a half, primarily written on a PAN-writer typewriter in the Osaka dialect and almost exclusively using the hiragana syllabary. All of these details are significant; the typewriter was of a rare and obsolete variety, the dialect is known for its ability to communicate emotion and humor, and the phonetic hiragana syllabary is the simplest of the main character sets used in the Japanese writing system.

In an article published in the Autumn 1996 issue of Critical Inquiry, anthropologist Marilyn Ivy classified these letters according to four categories: “Threat letters,” “written challenges,” “warning letters,” and “end of hostility letters.” On April 8, the following letter — which Ivy classifies as a “threat letter” — was sent to the police and later published by the press:

“To the stupid police:

Are you idiots? What are you doing with so many people? If you were pros, you would catch us. Because you guys have such a high handicap, we’re gonna give you some hints.

[The kidnapping] wasn’t an inside job.

There weren’t any of us within the police.

Also none within the Mizubo kumiai [the union which owned the warehouse in Ibaraki where Ezaki was held].

The car we used was gray.

We bought our food at Daiei Supermarket.

If you want to learn more, put an ad in the newspaper.

If you can’t catch us after this much info, you guys are just thieves of the taxpayers’ money.

Should we also kidnap the head of the prefectural police?”

In a time-honored criminal tradition utilized by everyone from Jack the Ripper to the Unibomber, these letters would become a hallmark of the case. They taunted their recipients, insulted them, and relayed “clues,” sometimes all in the same breath. They were signed, “かい人21面相,” or “kaijin nijūichi mensō.” Roughly translated, the phrase means “The Mystery Man With 21 Faces” — but over time, it has more frequently been translated as something more sinister: The Monster With 21 Faces.

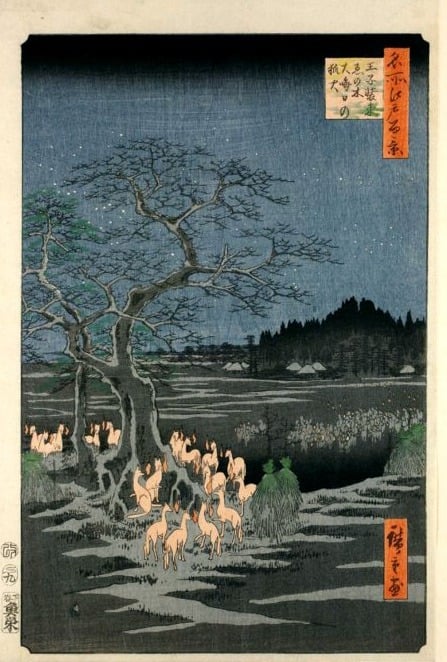

The moniker, too, is significant: It was drawn from the works of Tarō Hirai, who, writing under the pseudonym Edogawa Ranpo or Rampo, was one of the main architects of modern Japanese detective and mystery fiction. One of Rampo’s main protagonists, a Sherlock Holmes-esque figure named Kogoro Akechi, had his own version of the Baker Street Irregulars; called the Boy Detectives Club, this group of young crime-busters starred in their own series in which they faced off regularly with a gentleman thief going by the name “The Fiend With 20 Faces.” (If you’ve played Persona 5, you’ll probably recognize it as a flipped script riff on Rampo’s works.) The Monster With 21 Faces, it seems, was intent on one-upping the fictional criminal mastermind.

During this time, several other events occurred targeting Glico: Two fires believed to be instances of arson broke out at Glico facilities, while an anonymous phone call made to the company stated that if they paid the equivalent of $1.3 million USD, the campaign of harassment would cease. There was another kidnapping, as well — not of Ezaki, but of a young man who was abducted and ordered by his kidnappers to appear at a restaurant to collect the demanded $1.3 million. Police apprehended the man, but released him after a friend who had witnessed the kidnapping verified the story.

But in May of 1984, the Monster With 21 Faces, whoever they might have been, launched a truly monstrous plan: In letters sent to news organizations in the Osaka area, the Monster claimed to have laced numerous packages of Glico sweets with potassium cyanide and planted them on store shelves among regular candy. Shops and groceries accordingly yanked Glico’s products from their shelves; potassium cyanide is, after all, a highly lethal chemical compound, so the concern for public safety was not misplaced. But although no evidence of poisoning was ultimately discovered at the time, the threat did have a measurable effect on Glico: By July that year, the company stood to lose an estimated $130 million in sales and was prepared to lay off as many as 1,000 workers, according to the New York Times. (Later figures put the loss at $21 million.)

This outcome seemed to satisfy the Monster: On June 26, they sent a letter calling for a cease-fire — what Marilyn Ivy termed an “end of hostility letter.” It read:

“To our fans throughout Japan:

We’re satisfied. The president of Glico has already gone around with his head hanging down long enough. We would like to forgive him.

In our group there’s a 4-year-old kid — every day he cries for Glico. We also haven’t eaten any for a long time — and we used to eat it all the time.

It’s a drag to make a kid cry ‘cause he’s deprived of the candy he loves.

So we’re also really upset. It would be great if we could forgive Glico so the supermarkets could sell their products again. …

Japan has gotten terribly hot and humid, so when our ‘work’ is done, we want to go to Europe — Geneva, Paris, London — we’ll be in one of those places.

The police have done a good job — hang in there and don’t give up! Even Sherlock Holmes couldn’t beat us, the “Monster With 21 Faces.”

If you read the story ‘Kaijin niu menso’ [‘The Fiend With 20 Faces’], you’ll get a lot smarter.

The police’s ‘European Tour’

‘Let’s go to Europe to catch the Monster With 21 Faces!’

Let’s bring Pocky — the traveler’s friend! Delicious Glico products — we’re eating them too!

See you in January of next year!”

It’s not known what Ezaki or Glico ever did that would require “forgiveness” from the Monster; whether it was an actual incident or imagined slight remains to be seen. Either way, though, the Monster was true to their word: After that letter, they left Glico alone.

But that didn’t mean they were done with the rest of the world.

The Fox-Eyed Man, The Video Man, And The Poisoned Candy

Interestingly, though, when the Monster With 21 Faces returned, it wasn’t in Europe, and it wasn’t in January of 1985, contrary to the claims laid out in their cease-fire letter: They remained in Japan and resurfaced quite soon. They did, however, shift their focus. No longer did they hold Glico in their cross-hairs; instead, they targeted a number of other well-known food and confectionery producers — six in all.

They went to Marudai Food Company, which is headquartered in Takatsuki, about 25 kilometers from Osaka, first — and unlike Glico, the company agreed to pay off the Monster in exchange for a halt to the harassment the company had been experiencing. The idea, however, wasn’t just to make the payment; it was for the money exchange itself to be a police sting aimed at capturing the Monster. Accordingly, on June 28, 1984, an investigator disguised as a Marudai employee took 50 million yen — the agreed-upon amount — and boarded a train traveling from Osaka to Kyoto. The drop point was to be marked with a white flag along the train tracks; the money was to be tossed off the train at this point.

Aboard the train, the investigator acting as the Marudai employee spotted a suspicious man watching him — a man he described as having a powerful build, short, permed hair, glasses, and “eyes like a fox.” The Fox-Eyed Man, as he became known, debarked at Kyoto and hopped immediately on another train headed back for Osaka. Another investigator who had been stationed at Kyoto attempted to tail him, but lost ultimately lost him — and although it’s never been conclusively determined whether the Fox-Eyed Man was either the Monster With 21 Faces himself or a member of the group going by that name, or simply a man with a distinct appearance who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, it’s possible this incident represents an escape of a possible suspect.

Next up: Morinaga, whom the Monster With 21 Faces targeted in the fall of 1984. As had been the case with Glico, the initial contact made with the company was aimed at extortion — and again, the attempt came through the mail. Letters addressed to Morinaga’s Tokyo headquarters instructed the company to pay out what was then the equivalent of $410,000 or suffer the consequences. The Monster didn’t name those consequences; however, after Morinaga declined to cooperate, a letter sent to various news organizations on Oct. 8, 1984 informed both the company and the public what to expect:

“To moms throughout Japan:

In autumn, when appetites are strong, sweets are really delicious.

When you think sweets — no matter what you say — it’s Morinaga.

We’ve added some special flavor.

The flavor of potassium cyanide is a little bitter.

It won’t cause tooth decay, so buy the sweets for your kids.

We’ve attached a notice on these bitter sweets that they contain poison. We’ve put 20 boxes in stores from Hakata to Tokyo.”

It was the same threat the Monster had levied at Glico — but this time, it wasn’t an empty one: A rapid search of groceries, combini, and other stores immediately yielded boxes of Morinaga sweets with a typewritten label pasted to the outside carrying messages like, “Danger, contains poison. You’ll die if you eat this. The Monster With 21 Faces.” The packages tested positive for lethal doses of potassium cyanide. Between October of 1984 and February of 1985, 21 such packages were located. Later letters also claimed that the Monster intended to release more poisoned sweets in the future — but without the benefit of the added warning labels.

As with the Marudai incident, the Morinaga one also yielded a suspect who, again, eluded capture. Security footage recorded at a store in Osaka on Oct. 7 appeared to show a many placing an object on a shelf which was later discovered to hold potassium cyanide-laced candy. The footage was of poor quality; the store had been using the same tape to record its security footage over and over again for more than a year, which had dramatically degraded its quality, on top of which were the usual issues of poor lighting and a low-quality lens. But an analysis and enhancement by Japan’s national public television organization, NHK, yielded an image of a man wearing a Yomiuri Giants baseball cap, glasses, and permed hair — an image which was subsequently made public on Oct. 15. It’s not clear whether the man, who became known as Video Man, was the same man the investigator in the Marudai case had called the Fox-Eyed Man; either way, though, Video Man was never located.

The Fox-Eyed Man may have resurfaced once more, though. In November of 1984, the Monster With 21 Faces had set their sights on House Food Corporation — and, as had been the case with Marudai, the company worked with the police to arrange a sting operation disguised as a money drop. The Monster had demanded that House Food deliver 100 million yen, or about $410,000 USD at the time, to a rest stop on the Meishin Expressway near Otsu, just outside of Kyoto; they had been instructed to hide the money in a can underneath a white cloth. However, although the cloth was located, the can was missing, causing the investigators to call off the operation.

It later emerged that officers from the Shiga prefecture police had investigated a station wagon near what turned out to be the drop spot roughly an hour earlier. The station wagon had its engine running, but its headlights off; and when the officers approached, they found in the driver’s seat a man wearing a gold cap low over his eyes and with a pair of wireless headphones plugged into a wireless receiver in the front seat with him. The station wagon drove off — but although the Shiga officers attempted to give chase, they eventually lost their quarry.

The station wagon, which turned out to have been stolen, turned up sometime later at Kusatsu Station, about 13 kilometers from Otsu. The receiver had been used to listen to police from six prefectures, including those of the drop points. It’s believed that the driver may have been the Fox-Eyed Man from the Marudai drop.

The Final Letter And The End Of The Line

(CW for this next section: Suicide.)

The Monster With 21 Faces continued to target food and confectionery companies into 1985, always with the same MO — but no suspects were ever satisfactorily identified. After a composite sketch of the Fox-Eyed Man was released to the public in January of 1985, Manabu Miyazaki, an “outlaw,” as he called himself in a 2005 interview with the Japanese news outlet Asahi, with family ties to yakuza, was accused and brought in; he bore a striking resemblance to the composite sketch. However, his alibis for the scheduled money drops checked out, and he was later released.

But in August of 1985, something happened that may have made the Monster reassess their activity: A police officer from Shiga prefecture who had worked on the case died by suicide. Shoji Yamamoto, formerly superintendent of Shiga’s prefectural police, had been relieved of his post and reassigned to the National Police Agency just before his death; although UPI noted at the time that there was “no definite indication it was linked to [Yamamoto’s] participation in the ‘Man With 21 Faces’ gang case,” the report did go on to say that Yamamoto’s “associates said [he] had been embarrassed by an error made by his subordinates in failing to arrest suspects involved in the drama last fall” — meaning the failed sting operation intended to have been carried out at the Meishin Expressway drop point. According to UPI, “Yamamoto apologized to the public after officers under his command came across a car carrying one of the suspects last November but let him slip away.”

Several days after Yamamoto’s death, the Monster sent one last letter to several news organizations:

“Yamamoto of Shiga Prefecture Police died. How stupid of him! We’ve got no friends or secret hiding place in Shiga. It’s Yoshino or Shikata who should have died. What have they been doing for as long as one year and five months? Don’t let bad guys like us get away with it. There are many more fools who want to copy us. No-career Yamamoto died like a man. So we decided to give our condolence. We decided to forget about torturing food-making companies. If anyone blackmails any of the food-making companies, it’s not us but someone copying us. We are bad guys. That means we’ve got more to do other than bullying companies. It’s fun to lead a bad man’s life.”

Like all the other letters, it was signed, “The Monster With 21 Faces.”

And that was the last we’ve heard from them. They never attempted to extort another food company. They never attempted to poison anyone else. And they never appeared in Europe, as far as we know.

And they probably never will — just as we’ll probably never know who the Video Man was, who the Fox-Eyed Man was, whether they were the same man, whether they were both actually connected with the Monster With 21 Faces, and, indeed, whether the Monster was a group of people or just one person working alone.

The questions persist.

But we’re at the end of the line. The statute of limitations ran out on Katsuhisa Ezaki’s kidnapping in 1994 and on the poisonings in 2000. All told, the case involved 28 crimes, 1.3 million investigators from prefectural police forces in five prefectures, the questioning of 125,000 people, and 28,000 tips, according to a 2000 report from the CBS Business Network — and, notably, it was the first time the National Police Agency failed to make an arrest in a case they were investigating, according to the Japan Times. Said Setsuo Tanaka, then NPA chief, in a statement in February of 2000, “It is extremely regrettable that we could not apprehend suspects. It is indispensable that we make this an important lesson for our future investigations.”

Although Katsuhisa Ezaki still doesn’t have any idea who was actually behind his abduction, he made it through the ordeal with extraordinary resilience; he’s still president of the Glico Group, as it’s now called, today. “I haven’t forgotten the crime entirely, but after 16 years I hardly remember it in my daily life,” he told the Japan Times in 2000; his main wish — and his message for the Monster With 21 Faces, if they’re still out there — was that he didn’t want them to “repeat this kind of crime” ever again.

Others have, though. As the Monster With 21 Faces predicted, numerous copycat crimes have been carried out in the decades since the original case, including one as recent as 2014. They’re not always — and, in fact, usually aren’t — successful; they do, however, still occur. No doubt those behind them wish to share in the Monster With 21 Faces’ notoriety.

I’d be careful what you wish for, though.

Because some wishes?

Well, let’s just say it’s best if they don’t come true.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via PublicDomainPictures/Pixabay; Bakkai撮影<レタッチ済, Fumihiko Ueno/Wikimedia Commons, available under CC-BY-3.0 Creative Commons licenses; Amazon; Wikimedia Commons (1, 2), available under the public domain]

I wonder if the Monster with 21 faces was inspired by the Tylenol murders in Chicago in 1982?