Previously: How To Be A Nanny In A Haunted House.

It’s often spoken of as one of the most haunted houses in America — and it’s no wonder that it is: The things that are said to have gone on in the grand home known as the Congelier Mansion in Pittsburgh, Pa. are truly the stuff of nightmares. Indeed, when I first heard the stories of the place, I intended to turn the topic into a “Haunted Road Trip” piece. But when I started to look a little deeper, something… didn’t add up. A lot of things didn’t add up, actually. And the more I looked, the more it became clear that the Congelier Mansion… never existed at all. Or at least, not in the form the stories insist it does.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

I haven’t quite been able to unravel exactly how it became such a pervasive legend. I’m not sure if it’s as talked about locally as it is on the internet — but two things are certain: It’s almost completely fabricated, and the online world can’t get enough of it (it’s been floating around at least since the early 2000s). So, before we figure out where and how the whole thing starts to fall apart, let’s take a look at the legend as it stands, shall we?

The story goes something like this:

The Beginning

In the 1860s, Charles Wright Congelier, having made his fortune in the South during the Reconstruction era following the American Civil War, built a house in Pittsburgh and moved there with his wife, Lyda, and their maid, Essie. The house was located at 1129 Ridge Avenue in the Manchester neighborhood of the city’s north side — and it was a beauty: Huge and ornate, it overlooked the area where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers merged into the Ohio River — and soon, Congelier and his mansion became known for their elaborate parties, which played host to some of Pittsburgh’s most notable business magnates.

Then came the winter of 1871.

You see, Congelier had begun having an affair with Essie — and Lyda found out.

It’s not known whether the affair was consensual on the part of both parties or whether Congelier had forced his employee into the arrangement; my money would be on the latter, though — especially if there were post-Civil War racial dynamics at play (the stories don’t say if there were, but it’s certainly possible, and even likely) — which makes everything that happened next just that much worse.

It’s said that Lyda went in search of Essie one day when the maid didn’t respond to her employer’s summons — and that when Lyda approached the closed door of Essie’s room, she heard certain… noises coming from behind it. Knowing that there was only one possibility for who could be shut up in that room together, Lyda flew into a rage, retrieved both a butcher knife and a meat cleaver from the kitchen, and went back upstairs to wait. When Essie’s door opened, Lyda ambushed the two people inside, slaughtering both her husband and the maid.

She was found by a neighbor several days later, seated in a rocking chair in the kitchen, clutching Essie’s severed head in her lap.

Once an event like that has occurred in a place, the residual energy has a habit of clinging to the walls, floors, and ceilings — so it’s no surprise that the house on Ridge Avenue stood empty for years afterwards. In 1892, the railroad finally purchased it, intending to use it as apartments for their workers — but no one wanted to stay there for long. They heard things, the railroad workers said: A crying woman, screaming, the sound of a rocking chair creaking where there were no rocking chairs to be found. The railroad gave up the house just two years later, leaving it vacant once more…

…Until Dr. Adolph C. Brunrichter bought it.

The Doctor’s Experiments

No one really knew much about what went on in what had once been the Congelier Mansion while Dr. Brunrichter was in possession of it; however, on Aug. 12, 1901, the neighbors learned more than they ever wanted to know. First, they heard a woman screaming from inside the house — then, they witnessed an explosion rocking the building, blowing out its windows and sending cracks running up and down the sidewalk. When the police came to investigate, a gristly scene greeted them: Six decapitated women, each with their severed heads hooked up to various pieces of electrical equipment in Brunrichter’s lab.

The doctor, it seemed, had been experimenting with immortality. From what the police could tell, his “work” had been aimed at trying to keep human heads alive after they had been separated from their bodies. The explosion had been caused by an issue with the equipment.

But Brunrichter was never found. His remains weren’t in the house, so it was presumed he had escaped the explosion alive — but he was never found and held accountable for his crimes. He may have surfaced in New York several decades later, but the old man who had been brought in by the police for disturbing the peace was determined to be a harmless drunk and released. He was never heard from again.

The Evil Ends

Following this explosion and Brunrichter’s disappearance, the house again stood vacant for some time. It began to gain its reputation for being haunted, with several mediums conducting investigations and allegedly experiencing objects being thrown by forces unseen and the sense of a “fearsome presence.” Thomas Edison is also said to have had his great mind captured by the story of the Congelier Mansion; in fact, it may have been one of the inspirations for his ultimately-never-constructed spirit telephone.

Only one other attempt was made to turn the building into something useful: In the 1920s, the Equitable Gas Company bought it for the same reason the railroad had purchased it 30 years prior — to use it as employee housing. And here, we have a case of history repeating itself: The gas company employees, like the railroad workers before them, experienced things they couldn’t explain in the house — noises, footsteps, the creaking of a rocking chair. But unlike the railroad workers, they ultimately experienced something much worse: The unexplained deaths of two of their numbers. The deaths were chalked up to accidents by the police… but the workers knew something else was going on.

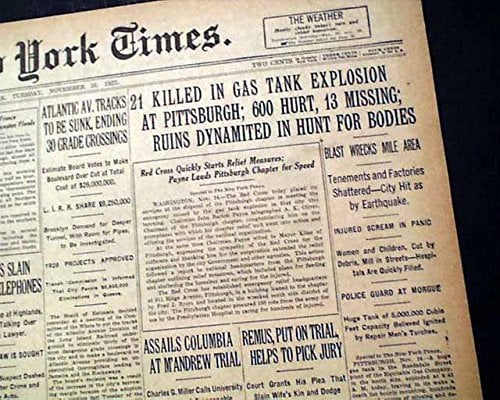

But soon, the house’s horrible reign would end: On Nov. 14, 1927, the Equitable Gas Explosion killed 28 people, injured another 500… and leveled 1129 Ridge Avenue.

The Congelier Mansion was no more.

The Truth Of The Matter

It’s quite the story, isn’t it? It’s got all the hallmarks of a classic tale of terror: Betrayal; body horror; science gone wrong; strange phenomena; untimely deaths; and ultimately, a horrible and spectacular end. But here’s the thing: It’s just that — a story. There’s no evidence that the “Congelier Mansion” even existed at all, let alone that any of the horrific events said to have occurred at it ever happened.

Two enterprising researchers have thoroughly debunked each aspect of the Congelier Mansion’s alleged history: Author and folklorist Stephanie Hoover of the site Clouded In Mystery, and historian Troy Taylor of Prairie Ghosts. Both Hoover and Taylor found that there are no records of anyone named Charles Wright Congelier or Lyda Congelier living in Pittsburgh at the time of the alleged double murder; additionally, there are no police records or newspaper articles about the alleged murder having happened in the first place. According to Taylor, there’s also no evidence that Dr. Brunrichter ever existed, nor that the railroad owned the house at any point. The Equitable Gas Company did use several buildings in the neighborhood as employee housing at one point, but no worker deaths occurred on the property during this time.

The only death connected with someone named Congelier in the area of town where the Congelier Mansion was allegedly located occurred during the gas explosion. According to an interview with descendants of the Congelier family conducted by Hoover, 29-year-old Mary Congelier — who is often erroneously referred to as “Marie” — suffered a severed artery in her leg due to a shard of glass sent flying by the explosion and died as a result. She left behind five children, who were then raised by relatives who actually did live at 1129 Ridge Avenue — which by the way, wasn’t damaged at all in the explosion, other than the shattered window that killed Mary. The 1929 city directory identifies these relatives as John Congelier, a barber, and his wife, Louise. The family moved away from the house in the 1950s.

It’s also worth noting that the timeline of the house’s “origin story” — by which I mean the tale of of Charles and Lyda Congelier and Essie the maid — is… a bit suspect. Congelier was meant both to have made his fortune during Reconstruction, and to have built the mansion in the 1860s; however, the Civil War didn’t end until 1865. To be fair, it’s not impossible that he might have become wealthy, moved his family north, built a house, and have been settled in the house long enough to have become a fixture of Pittsburgh society by 1871 — but unless he got rich essentially overnight, it’s more than a bit implausible.

But what of the photos? Every piece about the Congelier Mansion floating around the internet features the same photographs, which we’re meant to take as depicting the house itself. Surely that’s evidence of the mansion’s existence, right? After all the camera doesn’t lie… does it?

I hate to break it to you, but yes, the camera does lie. All of those alleged photographs of the mansion depict other locations entirely: The images seen here are photos of Franklin Castle, also known as Tiedemann House, in Cleveland, Ohio; the red-roofed building seen here is actually Keating House in Indooroopilly, a suburb of Brisbane in Australia (and the red roofs are a thing of the past, besides — the house is head-to-toe white now); and this black-and-white image — the same one seen here — is really of an abandoned hotel/health resort in Zippendorf, which is located in the German city of Schwerin.

(It took a lot of work to hunt down the true identity of that last one, by the way. It appears in tons of pieces online about spooky, abandoned, and allegedly haunted locations — not just pieces about the Congelier Mansion — and it’s almost never credited or sourced properly; as such, narrowing the field wasn’t easy. Eventually I managed to trace it back to Wikimedia Commons; it’s available there under a Creative Commons license, which explains its ubiquity. The image isn’t fully identified there, though; it’s just titled “The Haunted House Das Geisterhaus.” So, I had to keep digging a little more — and eventually, I finally unearthed a whole bunch of photos of the same building, along with an actual description of what and where it is. For the curious, here are those photos.)

Also, as Taylor noted, the house that once stood at 1129 Ridge Avenue wasn’t a mansion; nor was it built in the 1860s. Rather, it was built in the late 1880s — and it was a row house, a working class family’s home, not a place of grandeur befitting a wealthy family.

Besides, there’s one other reason none of those photographs could depict the Congelier Mansion, even if the place was real: It blew up in 1927. The photos, however, are clearly all recent — which means they couldn’t possibly be of the Congelier Mansion. Modern photographs can’t take pictures of the place because there’s allegedly nothing left to take pictures of at all.

The Congelier Mansion? Turns out it’s nothing but a myth — a haunted house that never was. Still, though — it’s fascinating how the story has stuck around and spread, growing with each new telling, despite its complete lack of truth. The imagination is truly an incredibly thing; sometimes, we want certain things to be real so much that they somehow… are. We give them life by sharing their stories.

Maybe we’re the ghosts, then.

Maybe the true haunting is just our own overactive imaginations.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via na4ev, moritz320, ArtCoreStudios/Pixabay; Amazon; Harald Hoyer/Wikimedia Commons]