Previously: The Taman Shud Case and the Somerton Man.

Since the publication of Erik Larson’s The Devil in the White City, the name of H. H. Holmes has his status as America’s first serial killer has become common knowledge. But nearly a decade before Holmes’ “Murder Castle” wreaked terror upon the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, there was another serial killer on the loose on the United States—and unlike Holmes, this one was never caught. Between 1884 and 1885, the city of Austin, Texas, had one very good reason to keep their doors locked and bolted at night: The Servant Girl Annihilator.

The term itself was, perhaps unsurprisingly, coined by a writer: William Sydney Porter, more commonly known as noted author O. Henry. Porter, who was living in Austin at the time of the murders, wrote in a letter to his friend Dave Hall dated May 10, 1885, “Town is fearfully dull, except for the frequent raids of the Servant Girl Annihilators, who make things lively in the dull hours of the night.” Although no contemporary newspaper articles referred to the murders by the name “The Servant Girl Annihilator,” Porter’s morbidly perfect phrase stuck after the letter containing it was published in his weekly, The Rolling Stone.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

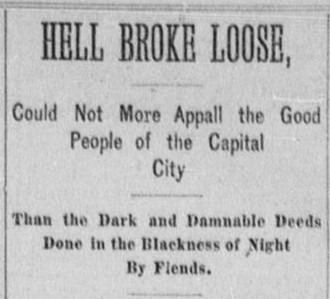

The Annihilator’s spree began on December 30, 1884 with Mollie Smith, a 25-year-old black cook who was found on the ground next to the outhouse behind her employer’s home. Eliza Shelly, another cook, had her head nearly hacked in two by an ax on the evening of May 6, 1885. Three weeks later on May 22, another servant, Irene Cross, was found having been stabbed a number of times by a knife; a reporter on the scene said it also looked like she had been scalped. Mary Ramey, the 11-year-old daughter of a servant, was dragged to a washhouse, stabbed through the ear, and raped on August 30. Her mother, Rebecca, had been knocked unconscious while she slept, ensuring the perpetrator wouldn’t be interrupted. Gracie Vance and her boyfriend, Orange Washington, met their ends on the night of September 28; their bodies were found behind Gracie’s employer’s house, Washington having been hit in the skull with an ax and Vance with her head beaten so severely it was described as “almost… a jelly.”

Finally, Christmas Eve that year saw not one, but two murders—and unlike all of the previous killings, they were of wealthy, white women. First, Sue Hancock was found by her husband in their backyard with her split open by an ax and a sharp, thin object lodged in her brain; an hour later, Eula Philips was found naked in an unlit alley behind her father-in-law’s home in the most well-to-do neighborhood in Austin. Timber placed across her arms pinned her down, her skull had been smashed by an ax, and she had been raped.

And then, the murders just… stopped. No one knows why. Some credit the increase in police presence, with more officers posted around town and tasked with finding out everything they could about any newcomers; others say it was the creation of a citizen’s vigilance committee and the promise of rewards for capture that scared the perpetrator straight; some even claim it was the construction of the Moon Towers that keep the city lit at night, although those weren’t built until ten years after the fact. It’s presumed that the killer left the city, but we don’t know for sure. What we do know is that of the 400-odd men that were arrested that year in connection with the murders, none were successfully tried for the crimes.

How do we know these unfortunate souls all fell victim to the same killer? Certain commonalities link them together: All of them, for example, were attacked indoors while sleep in their beds. Five of them were then dragged outside and killed. Three of them were mutilated once they had been taken outside. Six had had some sort of short object driven into their heads through their ears. And all of them were posed in a similar manner. These threads draw enough of a connection between them that we’re fairly certain they were perpetrated by the same person… although we still have yet to discover exactly who that person might be.

No supposedly eyewitness accounts even agree on what the suspect looked like. Some reported him to be white; others described him as dark; and still others called him “yellow.” He wore a Mother Hubbard dress, or he wore a slouch hat; he wore a rag that covered his face, or he didn’t. He worked alone, or with a partner, or even as part of a gang. He was magical, supernatural, invisible.

Or he didn’t exist at all.

What happened to him? Why has he been forgotten by all but the most dedicated of Austin historians? Perhaps it’s because he later overshadowed himself with a different name and greater crimes. One of the more popular theories posits that the Servant Girl Annihilator hopped a ship and crossed the Atlantic… only to resurface in London three years later, gaining the name of Jack the Ripper in the process. But conclusive evidence for this theory has yet be found; they cases have gone cold and to this day, remain unsolved. They’ve left their mark on Austin, though.

The Moon Towers are a testament to it.

Recommended reading:

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

Leave a Reply