Previously: Who Put Bella in the Wych Elm?

We know very little about the Somerton Man.

He was in his early 40s when he was found, five feet and 11 inches tall, clean shaven, with hazel eyes and greying strawberry blond hair. His smooth hands and well-kept nails showed that he was a stranger to manual labor. He dressed well, his outfit – a white shirt, a red and blue tie, brown trousers, a brown jumper, a brown and grey double-breasted coat, socks, and shoes – being of good quality, although missing all the labels. He wore no hat, and he carried no wallet.

And he was dead.

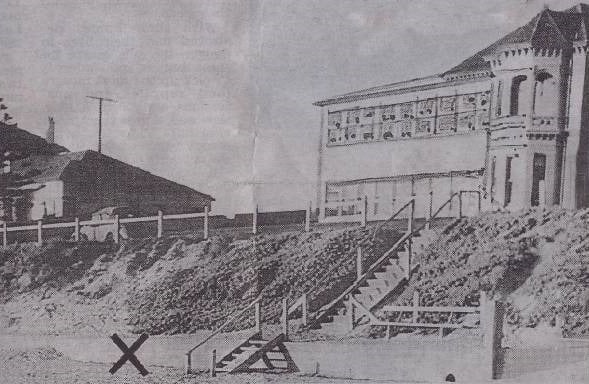

This mysterious body was discovered at 6:30am on December 1, 1948 under a streetlamp at Somerton Beach in Adelaide, Australia – and more than half a century later, we still don’t know who he is, what he was doing there, or how he died.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

We can tell you a lot about the state he was in when he was found: His head was resting on the seawall, and his feet were crossed and pointing towards the sea. His left arm was straight; his right was bent double. He had an unlit cigarette tucked behind his ear, and a half-smoked one resting on the right collar of his coat. He had in his pockets a used bus ticket from to St. Leonards, an used second-class train ticket to Henley Beach, an aluminum comb, a half-empty pack of Juicy Fruit, a pack of cigarettes, and a mostly empty box of Bryant & May matches. He had strong calf muscles, and his toes were wedged, as if he were either a dancer or simply accustomed to wearing pointed shoes. He had eaten a pasty some three or four hours before his death; there was also, however, blood mixed with the food in his stomach. Many of his other organs were also congested with blood, and his spleen was three times its normal size. Concluded the pathologist, “I am quite convinced the death could not have been natural… the poison I suggested was a barbiturate or a soluble hypnotic.” The one problem was that there were no foreign substances present anywhere in the body; clearly the pasty was not the culprit.

But that’s where what we know about him ends. We call him the Somerton Man, thanks to where he was found, but we don’t know whether he was seen alive at the beach the evening before his discovery. His teeth didn’t match the dental records of any person in Australia; his fingerprints didn’t match anyone in the English-speaking world No one recognized him. We don’t know whether he committed suicide or whether he was murdered, and we don’t know where he was from.

That didn’t stop the South Australia police from trying to crack the case when it was fresh, although by January 11, 1949, they had run out of leads. In a last-ditch attempt to turn up something – anything – about the nameless dead man, they began searching for abandoned possessions or lost luggage. Surprisingly, it worked: On January 12, detectives visiting Adelaide’s main railway station were shown to a brown suitcase. It had been deposited in the cloakroom on November 30 – the day before the Somerton Man’s discovery.

How do we know it was his? The presence of a thread card of Barbour brand orange waxed thread. This thread, not commonly available in Australia, matched the thread used the mend the inside of a pocket of the Somerton Man’s trousers. Also inside the suitcase were several items of clothing, many of which were missing the tags – just like the clothing the Somerton Man had been wearing when he was found. Three pieces of clothing in the suitcase did bear tags with the name “Kean” or “T. Keane” on them; however, after a failed search for anyone with those names, the police concluded that someone had purposely left them on to lead them astray.” A coat with stitching identified as American in origin indicates that the Somerton Man may have traveled there at some point; this, too, however, turned up no new leads. Neither did the remainder of the suitcase’s items: An electrician’s screwdriver, a table knife that had been cut down, a pair of scissors with sharpened points, and a stenciling brush.

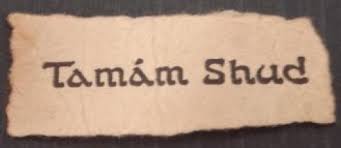

In April of that year, the body and its possessions were reexamined, leading events to take a surprising turn: In a small pocket sewn into the waistband of the Somerton Man’s trousers – a pocket which had been previously missed, although it is believed to have been intended to hold a fob watch – was a tightly rolled scrap of paper. The paper held two words printed in a distinctive typeset:

The newspapers erroneously reported the words as “Taman Shud”; unfortunately the mistake stuck, which is why the case of the Somerton Man is still often referred to as the Taman Shud case. The words are in fact the final sentence of the 12th century Persian poem The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam; the fact that they were typeset suggested that the scrap had been torn out of a copy of the poem. The police then began a search for the book, hoping that if they found the Somerton Man’s copy, they would unlock the key to his death.

The words, by the way, translate to this: “It is ended.”

And here’s where a strange cases gets even stranger, because the police did eventually find the book. In July of 1949, a man from Glenelg walked into the detective office with the book. He told the police that in early December – shortly after the Somerton Man had been found – he and his brother-in-law had gone for a drive in a car he kept parked by the beach. The brother-in-law found a copy of the Rubaiyat on the floor in the backseat; both men, however, had assumed it belonged to the other, so neither questioned its existence. They stuck it in the glove compartment, where it remained until they read a newspaper article about the search for a specific copy of the Rubaiyat. When they pulled it out of the glove compartment to examine it, they found that the last page had been ripped out – and it was an extremely rare first edition of the Edward FitzGerald 1859 translation, to boot.

Two further strange events emerged from this development, the first being that a telephone number had been penciled onto the back cover. It belonged to a young nurse, “Jestyn,” who lived near Somerton Beach, who, when questioned by the police, noted that she had in fact given a copy of the Rubaiyat to a man during the war. She had a name for them, too: Alfred Boxall. Boxall, however, turned out to be very much alive; he also still had the copy of the book the nurse had given him. The police returned to Jestyn with a cast they had made of Somerton Man, and although the reacted poorly – reports state that she almost fainted – she firmly denied knowing him.

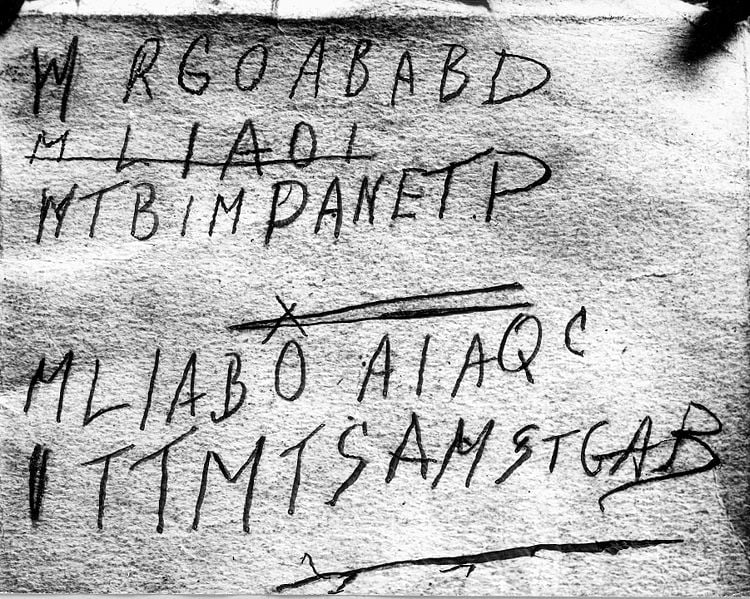

Faced with yet another dead end, the police returned to the book – and, upon closer examination with an ultraviolet light, found that beneath the telephone number were five jumbled lines of letters:

They looked to be some sort of code – but here the trail runs dry. The code was never solved; according to the Navy, it may even be completely unbreakable. The nurse’s daughter has recently come forward with her belief that her mother, who had remained anonymous until after her death, may have in fact been a Soviet spy who killed the Somerton Man after conceiving a child with him – but until DNA testing is carried out, this theory remains unsubstantiated. It is ended.

We think.

Recommended reading:

The Body on the Somerton Beach.

The 5 Creepiest Unsolved Crimes No One Can Explain.

New Twist in Somerton Mystery as Fresh Claims Emerge.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!