Previously: Who Was The Man From Taured — And Did He Even Exist At All?

Way back in 2015, when The Ghost In My Machine was still in its early years, I took a relatively brief look at a story that had been circulating for some time regarding a figure known as “the Man From Taured.” At the time, I’d come to the conclusion that the “mystery” was likely an urban legend; there was little to no information actually backing it up, with the tale mostly being repeated over and over as hearsay — no reliable sources cited. A year or two ago, though, I started seeing some chatter that the Man From Taured mystery had been solved: He was actually a man called John Zegrus, and he had been detained in Japan due to a forged passport circa 1959-1960.

I’ll admit that initially, I was skeptical; at first, I was mostly seeing the basic information of this possible solution passed around the same way the original Man From Taured story had been — that is, briefly, and without much in the way of citations to support the claim. But I figured it was worth looking into anyway to see if it actually checked out, because, well… that’s what I do.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

The short answer? The version of the story I had previously looked at is an urban legend — but, as is often the case with urban legends, it does appear to have its basis in a factual event. John Zegrus did exist; he did arrive Japan in 1959; and he did get into some trouble in early 1960 due to passport forgery, among other things.

Meanwhile, the long answer — the story of how Zegrus’ case was unearthed by modern-day internet sleuths, and his connection to the Man From Taured legend uncovered — is… quite a ride.

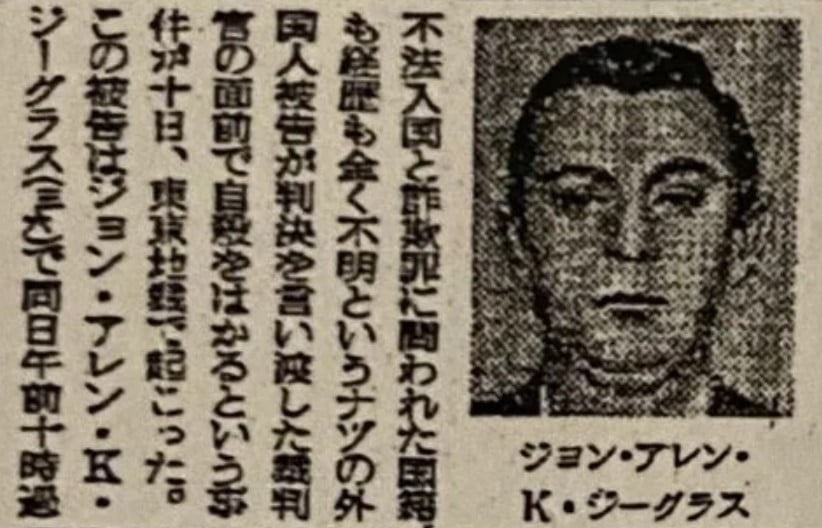

We’ve got three primary people to thank for uncovering the various bits and pieces that allow us to see the big picture here: Natanael Antonioli, who kicked this leg of the investigation off on Reddit in July of 2019; Julia Louis, who added to the search on the Forteana Forums under the username AnonyJ in March of 2020 and later published her findings in a writeup for the June 2021 issue of the Fortean Times; and Redditor and Note.com user taraiochi, who, in November of 2020, dug up Japanese news coverage of the Zegrus story from the time at which it was actually unfolding.

Additionally, I located a blog post from Hatena Blog user gryphon that I found to be enormously useful as I started looking into the whole thing myself, as it provided access to a key Japanese source — information contained within Atsuyuki Sassa’s book The Spies Who Passed Me By — I wouldn’t have been able to parse otherwise.

So: Who was John Zegrus — or, John Alan Zegrus, John Allen Zegrus, John Allan Kucher Zegrus, John Allen Kuchar Zegrus, and/or John Allen K. Zegrus, depending on the source — and what did he do, precisely? What happened to him? And how did he become immortalized in legend as the Man From Taured?

Let’s take a look, shall we?

The Facts In The Case Of John Zegrus, The Mystery Man Without A Nationality

The facts are these:

On Oct. 24, 1959, a 36-year-old man calling himself John Allen K. Zegrus entered Japan through Haneda Airport from Taipei, Taiwan, along with his 30-year-old wife, who was from South Korea, reported the evening edition of the major Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun on Aug. 10, 1960. In December of 1959, Zegrus attempted to defraud the Tokyo branches of both the Chase Manhattan Bank and the Bank of Korea out of some hefty funds: 200,000 yen plus an additional $140 in traveler’s checks from Chase Manhattan, and another 100,000 yen from the Bank of Korea. (Adjusting for inflation, that’s just shy of 1,200,000 yen today, or about $8,600; about $1,500 in traveler’s checks; and almost 600,000 yen, or about $4,300. All in all, that’s about $14,400 today. Not millions, sure, but still not insignificant, especially given the era.)

Zegrus was arrested in January of 1960 in connection with the attempted bank fraud — and upon his arrest, it was discovered that the passport he had used to enter Japan was forged.

Typically, a case like this would have been under the jurisdiction of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department’s Criminal Investigations Bureau. However, it ended up getting handed off to the Foreign Affairs Division of the MPD’s Public Security Bureau instead, where it was headed up by eventual first Cabinet Security Affairs Office chief Atsuyuki Sassa — then early in his career — due to what Zegrus claimed his background to be.

Sassa, who, in addition to his law enforcement and political career, also became a prolific writer over the course of his life, mentioned the Zegrus case several times in his published works. The most detailed discussion of it, however, makes up the fourth chapter of his 2016 book The Spies Who Passed Me By, titled, “Was He A Double Agent?” (This book has not been translated into English and is difficult to get a hold of outside of Japan; I am indebted to a May 2020 blog post by Hatena Blog user gryphon, which summarizes the information contained within this chapter of the book.)

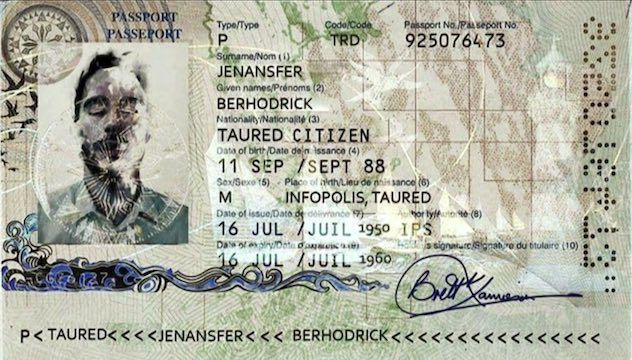

According to Sassa, Zegrus claimed to be “a mobile ambassador for the Negusi Habesi country and an American intelligence agent.” When asked where Negusi Habesi was, he pointed on a map to Ethiopia and claimed it was supposed to be written in a different script — one resembling Arabic. Zegrus’ homemade passport was “the size of a weekly magazine,” per Sassa, and contained a section intended to certify its eligibility which read, “Negushi Habesi Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary” and “Roving Ambassador … an ambassador who travels around the world without being stationed in one country.” According to Sassa, Zegrus claimed his arrest was “a violation of diplomatic privileges” and demanded to be released immediately.

Ergo: The case went to the Foreign Affairs Department. Just, y’know… in case. No one wants a diplomatic crisis or an international incident on their hands if they can help it, right?

Zegrus apparently claimed to have been born in the United States before moving to England via Germany and what was then Czechoslovakia, where he stayed until he completed secondary school. He claimed to have been a pilot in the Royal Air Force during the Second World War and spent time imprisoned in Germany as a POW. After the end of the war, he claimed to have lived for a time in Central and South America; to have worked as an intelligence agent for the U.S. military in Korea; to have been a pilot in Thailand and Vietnam; and then to have joined the Arab coalition in order to carry out a diplomatic mission for the Negusi Habesi. “I came to Japan to carry out a top-secret mission of recruiting Japanese volunteers for the Great Arab Coalition,” he said, according to Sassa.

Upon investigation, none of the biographical information Zegrus provided could be verified. Police subsequently indicted him on the grounds of having an unknown nationality.

The Aug. 10 article from the Yomiuri Shimbun was published on the occasion of Zegrus’ sentencing — and, apparently, attempted suicide in the courtroom immediately following the sentencing. He did not complete the attempt, and, following his recovery, was sentenced to one year in prison.

The Japanese media continued to cover the strange case during that time, with major papers such as the Asahi Shimbun and the Mainichi Shimbun publishing stories about it throughout Zegrus’ year of imprisonment. Additionally, Atsuyuki Sassas wrote in The Spies Who Passed Me By that Zegrus attempted to file a civil lawsuit from prison against the Superintendent General at the time, Bunbei Hara, accusing him of embezzlement and demanding $1 million in damages. The suit didn’t go anywhere (because it was absurd), and when Zegrus’ time was up, he was deported to Hong Kong. His wife, meanwhile, was deported home to South Korea.

Sassa didn’t know what happened to either of them after they left Japan — and there, seemingly, the story ends.

Except… it doesn’t. Not quite.

The plot thickens, you see, as the story travels — and, as it does so, it moves into legend.

From “Tuarid” to “Taured”: Playing Telephone With The Truth

The Zegrus story, it turns out, initially spread much more quickly than I might have thought: As both Natanael Antonioli and Julia Louis found, Zegrus-related news traveled globally via translated radio broadcasts as the court case unfolded. We know this, because the translations are available as public record: They’re in the published daily reports of the Foreign Broadcast Information Service, or FBIS.

Per the University of Washington’s library system, the FBIS was started in 1941 with the goal of providing English language translations of radio broadcasts from foreign countries and territories of interest. The collected published reports are pretty widely available; many of them — including the ones that are relevant to us here — are even available on Google Books.

Antonioli dug up a broadcast translation in the compilation of issues 156 through 160 of these daily reports dated Aug. 10, 1960 that describes precisely what was published in the Yomiuri Shimbun that same day. Meanwhile, Louis located another broadcast translation in the collection featuring issues 249 and 250 from 1961 which essentially offers a two-sentence summary of the entire case: In this summary, Zegrus is described as “a man without nationality” who was sentenced to a year’s imprisonment for “having illegally entered Japan and passing phony checks.”

However, there’s also evidence that the case was known about in some circles sooner than August of 1960 — not much sooner, but still prior to the first of the broadcasts documented in the FBIS daily reports: The transcript of a speech regarding the issue of passport control given on July 29, 1960 by British politician Robert Mathew, who represented Honiton (now part of East Devon) in the House of Commons, makes reference to the ongoing Zegrus situation.

It’s this speech which introduces the key element of what will — through a process not unlike that seen in the game of Telephone (the parlor game, not the supernatural ritual) — eventually become “Taured.” Roughly halfway through his remarks, Mathew told the following anecdote (emphasis mine):

“My hon. Friend may know the case of John Alan Zegrus, who is at present being prosecuted in Tokio. In evidence, he describes himself as an intelligence agent for Colonel Nasser and a naturalised Ethiopian. This man, according to the evidence, has travelled all over the world with a very impressive looking passport indeed. It is written in a language unknown and it has remained un-identified although it has been studied for a long time by philologists.

“The passport is stated to have been issued in Tamanrosset the capital of the independent sovereign State of Tuarid. Neither the country nor the language can be identified, although a great deal of time has been spent in the attempt. When the accused was cross-examined he said that it was a State of 2 million population somewhere south of the Sahara. This man has been round the world on this passport without hindrance, a Passport which as far as we know is written in the invented language of an invented country. I would stress, therefore, that passports are not very good security checks.”

There it is: “Tuarid.”

For what it’s worth, I’m not actually sure where Mathew got all of the stuff about “Tamanrosset” or “Tuarid” from; it’s not present in any of the contemporary Japanese reports or sources that documented the case, but I suppose it may have come up in the understanding of global geography at the time.

Regardless, it is pretty clear that Mathew made some errors here. “Tamanrosset” does exist, but the spelling is incorrect: Tamanrasset is the typical rendering of the city’s name in the Latin alphabet. It’s the capital city of the Tamanrasset Province, which is located in the southern region of Algeria. Meanwhile, “Tuarid” is believed to be a fumbling of “Tuareg,” as well as a misunderstanding of what the word “Tuareg” actually refers to: It’s not an “independent sovereign State,” as Mathew seems to have thought it was, but the name of a people. To sum up: Tamanrasset is a place populated by the Tuareg people, not a place located in the “Tuarid” (Tuareg) region.

But wait! There’s more!

Not too long after the House of Commons speech, the Yomiuri Shimbun article, and the FBIS broadcast, a Canadian paper — a tabloid based out of Vancouver, the Province — picked up the story: On Aug. 15, 1960, an article titled “Man With His Own Country…” appeared on page four, detailing the exploits and adventures of “John Allen Kuchar Zegrus,” as he’s identified. The article, which was first connected to the bigger picture by Natanael Antonioli, included the following information about Zegrus (emphasis again mine):

“John claimed to be a ‘naturalized Ethiopian and an intelligence agent for Colonel Nasser.’ The passport was stamped as issued at Tamanrasset, the capital of Tuared ‘south of the Sahara.’ Any places so romantically named ought to exist, but they don’t. John Allen Kuchar Zegrus invented them.”

This information matches that contained within Mathew’s speech, with some slight alterations. On the plus side, Tamanrasset is spelled correctly this time (hoorah!). However, it’s still mistakenly referred to as the capital of a region, rather than a place populated by a specific people (boo!). But, the main thing to notice is this: What Mathew called “Tuarid” has now been rendered as “Tuared.”

And, well… it’s not exactly difficult to see how one might get from “Tuared” to “Taured,” is it?

A Parallel Universe And A Locked Room Mystery: Or, How Fact Becomes Fiction

But wait! There’s EVEN MORE!

As Antonioli pointed out in a Reddit post in 2020, the Tuared story appears in several of Jacques Bergier’s books, which were primarily published in the 1960s and ‘70s; indeed, Bergier may have been the first to introduce some of the elements of Man From Taured tale as it was by the time I heard about it back in 2015. Antonioli noted that he found reference to “Tuared” in Bergier’s 1974 Mysteries Of The Earth; I was unable to get a hold of that particular volume, but I did locate Extraterrestrial Visitations From Prehistoric Times To The Present, also published in 1974, and found it to be present there, as well.

Bergier’s version uses the Tuared spelling, as opposed to Taured — but he moves the date of the events from 1959-1960 to 1954, when they’re typically said to have happened in modern tellings of the legend, and he introduces the hotel to the story. The mystery man doesn’t disappear from the hotel room, though; rather, he’s located within it when government officials arrive to verify his passport. (In this telling, the government supposedly “ordered the passports of all foreigners residing in Japan to be verified” in response to a series of riots believed to have been instigated by foreigners.) The mystery man with the “Tuared” passport keeps insisting his story to be true, although he is unable to convince anyone to believe him. He is eventually left “shut up in a Japanese psychiatric hospital,” per Bergier’s version of the story, where I assume we’re meant to believe he has remained ever since.

“Tuared” finally became “Taured” in Colin Wilson and John Grant’s 1981 book The Directory Of Possibilities, although as I previously noted, there’s just a single sentence mentioning the story there: “And in 1954 a passport check in Japan is alleged to have produced a man with papers issued by the nation of Taured.” And sometime between then and roughly 2013, the story had developed into what we would eventually come to know as the full “Man From Taured” incident, featuring the locked hotel room element, the mysterious vanishing, and the proposal of a parallel universe being at play.

I know, I know — 1981 to 2013 is a long gap. Unfortunately, I don’t have the resources needed available to me in order to trace exactly what happened to the tale during that space of time. I would image, though, that it developed much the way every other urban legend does: With the story getting passed on from storyteller to storyteller, each embellishing it a little as they told it, until eventually, it made its way onto the internet.

Thanks to the legwork of researchers like Natanael Antonioli, AnonyJ/Julia Louis, and taraiochi, though, it does seem pretty indisputable that the “Man From Taured” urban legend did, in fact, grow out of the real-life story of John Zegrus. He wasn’t a man from a parallel universe; he was just your run-of-the-mill con man.

I often say that some mysteries are better left unsolved. But this time? I’d argue that it paid off. For me, the story of how the mystery got solved is just as fascinating as the story told within the legend itself.

Now, then: Who’s up for a trip?

The whole wide world is waiting…

…As long as you’ve got your passport handy.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Bluesky @GhostMachine13.bsky.social, Twitter @GhostMachine13, and Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And for more games, don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via Ylanite, 652234, Pexels/Pixabay; screenshot/Google Maps]