Previously: The Nickelodeon Clock Man Mystery.”

As was the case for many middle-class kids growing up in the ‘80s and ‘90s, it was Big News in my childhood home when we got our first camcorder. I don’t recall ever being trusted with actually operating the camcorder, but I do remember being taught how it worked. But, hazy though my memories might be, I can say with total confidence that what happened when I was taught about the camcorder was absolutely nothing like what happens in the short horror video “Teaching Jake About The Camcorder, Jan. ’97.” For one thing, our camcorder didn’t have the ability to capture extra-dimensional beings in its footage. And for another, watching the footage back… didn’t have the same effect that watching it back does in “Teaching Jake About The Camcorder.”

Because the story of “Teaching Jake About The Camcorder” isn’t just what happens when the titular Jake’s father is teaching him about the camcorder. The story goes much deeper than that — and what’s hiding underneath it all is a story about memory, a story about grief, and a story about what happens we allow both of these things to consume us.

“Teaching Jake About The Camcorder” is the brainchild of video producer, writer, actor, comedian, musician, and general content creator Brian David Gilbert. (Yes, he does a lot.) Until fairly recently, Gilbert was a video producer at Polygon; towards the end of 2020, however, he struck out on his own, and he’s been running full tilt on his YouTube channel ever since. (If you’re interested in finding out more about him, he answers 27 questions about himself here. They range from the essential, like “Who is Brian David Gilbert?” and “What is Brian David Gilbert’s creative routine?” to the… less essential, like “What kind of voice would this drawing have?” and “White, wheat, or rye?”)

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

Now, to be fair, Gilbert has been making videos on his own time for several years; his YouTube channel was created in 2012, and the oldest videos on it currently date back to 2016. But he appears more or less to be doing this full time now, with the support of a successful Patreon campaign — and now that he’s got complete freedom over everything he makes, he’s been really leaning into his own brand of… well, whatever you call the things that he makes.

His videos tend towards the absurd, and often feature some pretty spectacular musical numbers — but sometimes they also veer into something… weirder. More… upsetting, I guess I’d say. Take “Earn $20K EVERY MONTH by being your own boss,” which I included in TGIMM’s newsletter for Patreon subscribers a few months ago: It starts as a parody of those get-rich-quick scams that insist you can, well, earn $20K EVERY MONTH by being your own boss, and quickly becomes an unsettling piece of horror that sort of makes your skin crawl.

“Teaching Jake About The Camcorder” is another piece of horror, although this time, there’s less comedy and more dread. There’s also a much deeper story to be found — as long as you’re willing to dig for it a little.

Look At You, Mr. Director!

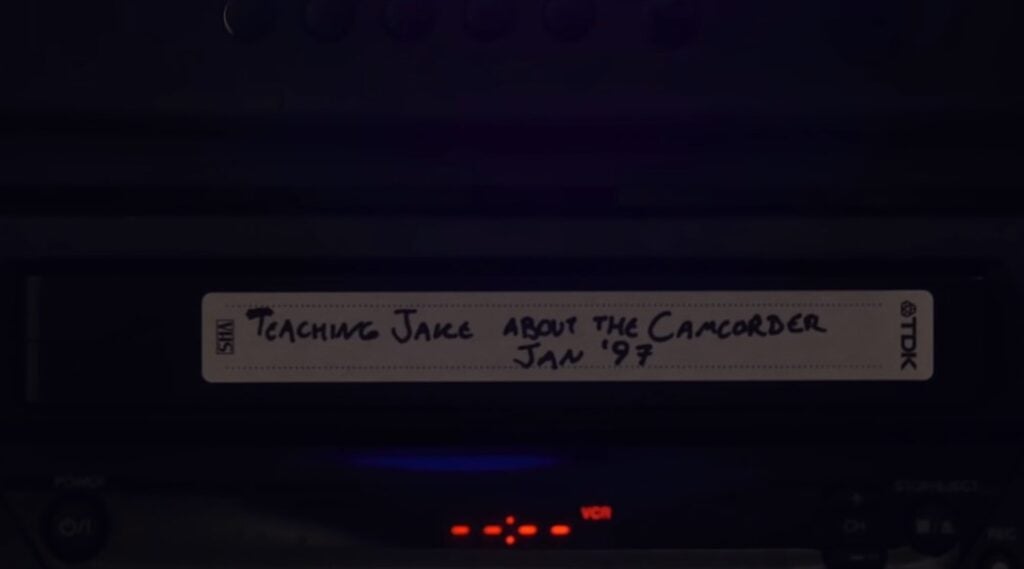

“Teaching Jake About The Camcorder” is made up of two nesting narratives. The outer frame positions us in a room with a television and a VCR; then, after we see someone’s hand push a VHS tape in the VCR and press play, we see the footage that makes up the inner portion of the story as it plays across the television screen.

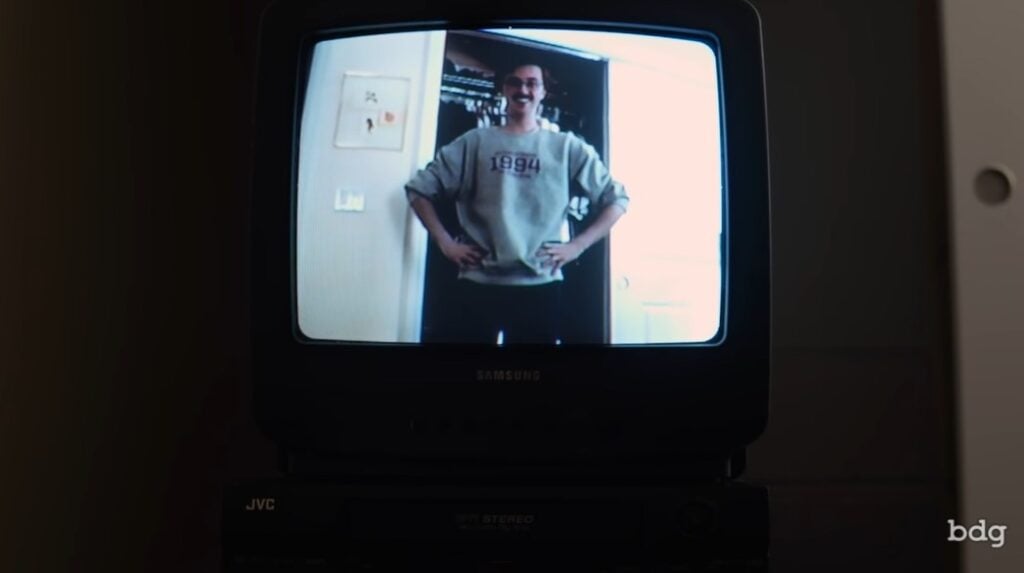

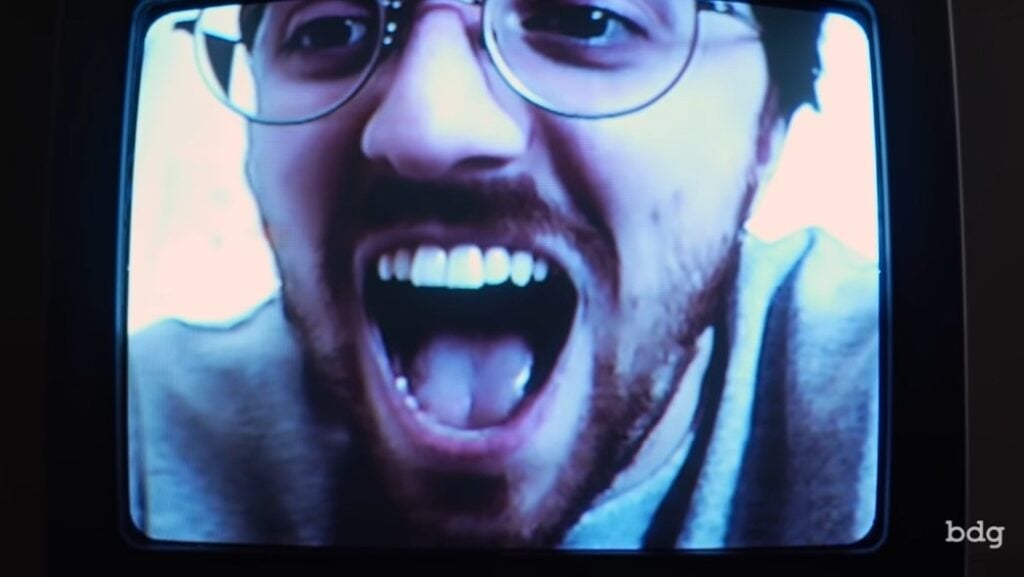

Initially, the footage depicts a short, somewhat comical scene of a young father teaching his small child how to use the family’s camcorder. It’s 1997, and it looks it: The father’s fair is floppy and brushed to one side; he wears glasses; he has a moustache; and his sweatshirt — crew neck, baggy, unfashionable — is adorned with the year 1994. “—steady,” he tells us, looking straight at the camcorder, “use both hands at all times. That’s some expensive technology you’re holding.” He backs up and stands before an open closet. He gazes adoringly at us. “Attaboy! Look at you, Mr. Director! Mr. Big Shot Director over here! The next Steven Spielberg, goodness!” he beams. He leans over to the left of the screen and calls through a dark, open doorway. “Hon, take a look — Jake’s holding it like a professional,” he says.

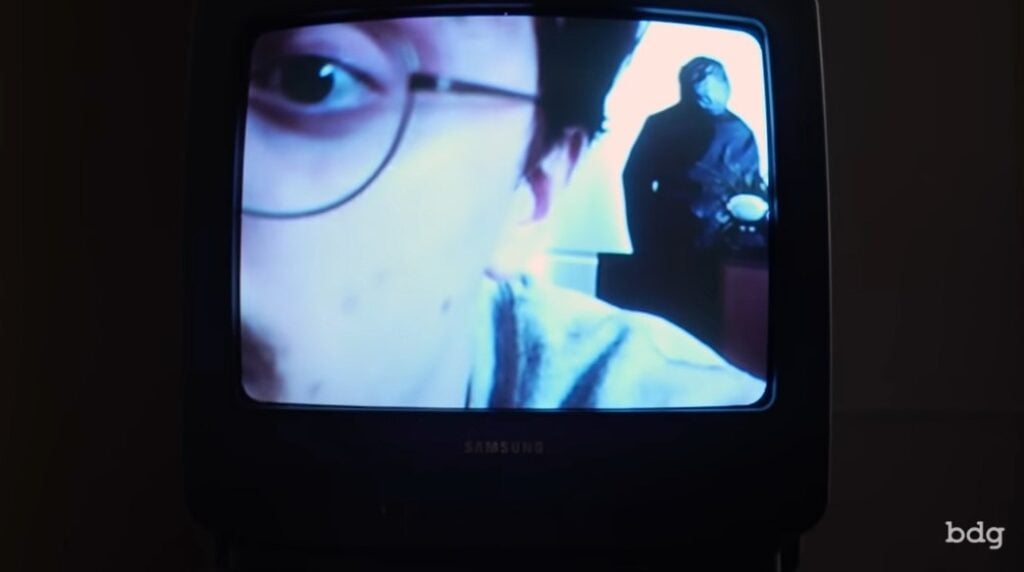

The camcorder begins zooming in on the father’s sweatshirt. He notices as he turns back. “Oh — you’re zooming in, bud. Look through the viewfinder,” he instructs. “The — the little tube thing on the top — hold on.” He reaches towards us and takes the camcorder, focusing it on his face.

“Okay. So — the only button you need to worry about is this red one right here,” he tells us. “Don’t press it right now! That’s going to start and stop the recording — and never press the rewind button, or else you might record over a precious memory. All right? So, we always want to keep the recording going forward. Okay, bud? Okay. We can always just start a new tape.”

We understand this to be very, very important.

Then the father backs up again. “Now keep me centered,” he instructs us. “Get my good side.” He strikes some poses, then gazes adoringly at us again. “Look at you! You’re a natural! Are you sure I never taught you this before? It’s like déjà vu! You’re so good, bud!”

He notices the camcorder slipping. “Oh, no — both hands, Jake,” he tells us, concerned. “Jake, both hands — Jake!” He rushes forward to grab the camcorder before it goes crashing to the ground.

The scene stops. The screen goes to static. And the tape begins to rewind.

This little scene would all seem fairly innocuous — just a short little home movie from a bygone era, a snapshot of one family’s life nearly a quarter of a century ago — if it weren’t for what happens after the tape begins playing again.

At first, it looks the same as it did the first time ‘round: A young father with dark hair, glasses, and facial hair backs up from the camcorder, saying, “Hold it steady — use both hands at all times. That’s some expensive technology you’re holding.” But at the same time, it’s… different. The father still has dark hair, but it flops straight down over his forehead, rather than sweeping off to one side. He still has facial hair, but there’s a beard to go with the moustache now — not just the moustache itself.

Other, smaller details differ during this second go ‘round — this second loop — as well, although they’re mostly less pronounced than they are with regards to the father’s physical appearance. The framing of certain shots isn’t always the same: This time, for instance, we can see the doorway to the left of Dad during the initial opening, whereas last time, all we saw was Dad standing in front of the closet; then, when the camcorder starts zooming in, it focuses on Dad’s face, rather than on his sweatshirt. The dialog, too, has tiny differences — this time, for example, it’s “You might accidentally record over a precious memory,” rather than simply, “You might record over a precious memory.”

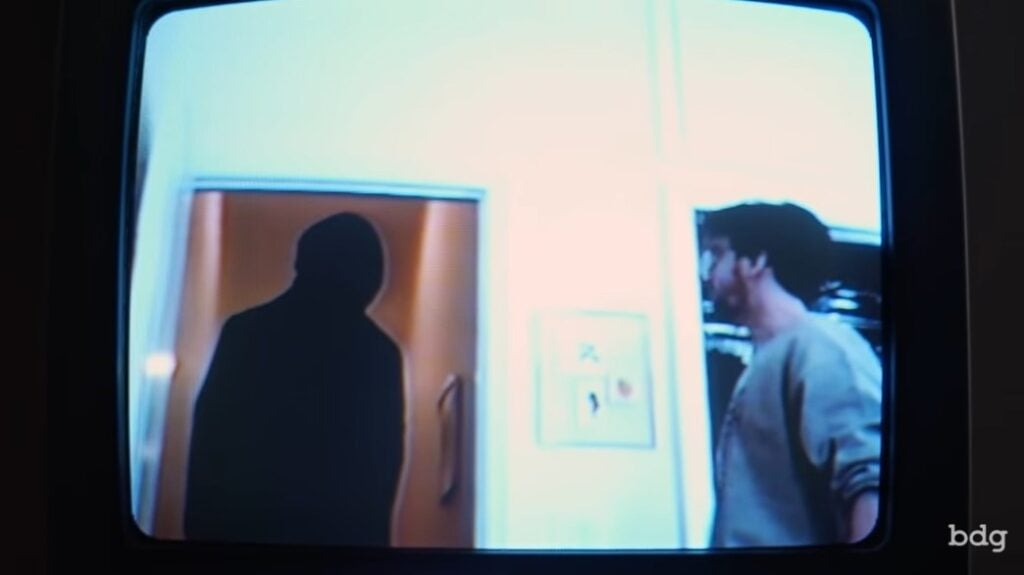

But the most jarring change is this: During the “Okay, so the only button you need to worry about” speech, there’s… someone else in the room with Jake and his father. We can see a dark figure on the right-hand side of the screen, lurking over Dad’s left shoulder. He doesn’t notice it — but we do.

Oh, we do.

Things continue as they did — mostly — until we get to, “Are you sure I never taught you this before?” Here, Dad stops and looks… confused for a moment. Like he feels like something isn’t right, but he doesn’t know what. But then he resumes with “Both hands, Jake,” before the scene cuts to static — a little sooner this time — and we rewind again.

We begin once more. And we will continue to do this — to watch the scene, to observes its differences, to rewind it and resume — again, and again, and again, until we have seen it a total of nine times. Sometimes, we see the father from the first loop — Moustache Dad. Sometimes, we see the father from the second loop — Bearded Dad. Sometimes we start from the top of the scene — “Hold it steady — use both hands at all times” — but sometimes, we start further on. With each loop, the scene recorded on the camcorder deteriorates in quality just a little bit, becoming darker and blurrier as the tape suffers wear and tear. And with each loop, the camera (not to be confused with the camcorder) that shows us the overall frame of the film — us sitting before a television watching a tape — zooms closer on the television on which we’re vieweing the tape, until finally, the room around us, the VCR, and even most of the television itself largely vanishes, leaving us with only the scene on the TV screen.

And each time, something different happens.

During Loop 3, there’s no dark figure, but Dad pauses after telling us to “never, ever press the rewind button”—and suddenly, he’s looking directly at us, as if he is seeing us for the first time in a long, long time. As if he is in the present with us, not a recording from the past. “Jake? Jake!” he says. “It’s good to see you, buddy,” he tells us. “You got so… you’re an adult! Wow!” He is proud of us — proud of what he sees. But then, a pause. And then: “Jake, I don’t know why—”

And then we’re rewinding again.

In Loop 4, the dark figure is back. He appears in the doorway as Dad is calling for Mom to “come take a look.” But Dad sees him this time. “Who are you?” he says, immediately on alert. “How did you get in my house? Who are you? WHO ARE YOU?,” he asks repeatedly, growing in volume, shouting, as some slight distortion appears in the background audio.

And then we’re rewinding again.

In Loop 5, Dad doesn’t give us the “the only button you need to worry about” speech. Instead, he asks, “Jake, why do you keep watching this tape?”

“Jake, I’m so thankful for the time we had together,” he says, “but… you can’t keep reliving it. That’s… that’s not going to bring me back. That’s not going to make you happy.”

He pleads with us to stop watching the tape: “Please. Please, Jake. Stop watching the tape.”

We rewind.

In Loop 6, Dad breaks off after “That’s some very expensive technology you’re holding.” He looks up. He breathes suddenly, sharply — as if he’s watching something come for him. For the first time, the camcorder pans away, all the way around until we’re facing the other wall of the room. When the camcorder pans back to the closet, Dad is gone. The screen goes black; we see static.

This time, we do not rewind — but in Loop 7 (if we can truly call it that; it may be something of a misnomer), Dad focuses the camcorder directly on his own face as he speaks directly to us. “Jake, I don’t know what it is that you’re trying to gain from replaying this video, but I… I can promise you, you’re not going to find it,” he says. “One tape isn’t going to hold the answer to… whatever.” He tells us he loves us. He tells us he doesn’t want us to “get stuck.” He asks us to say something. There is silence. “You’re not—” he begins —

— but then we’re rewinding again.

In Loop 8, Dad takes the camcorder after realizing that we’re zooming in. It closes in on his face — but this time, he’s not looking at us. He’s looking over to our left — to his right. His mouth opens, and a small, breathy sound comes out. The sound grows into a scream.

We rewind — but we can still hear the scream, even as the video winds back.

We go to static, and the camera zooms out a little. We can see more of the TV again, not just its screen.

It’s Moustache Dad — Loop 1 Dad. He sounds… tired as he repeats his lines. When he gets to “Attaboy,” he has a tone of finality we haven’t heard before—and then, instead of continuing, he turns and walks through the dark doorway to the left. He walks down the hallway. He opens another door, and he goes through. We can hear him walking away, long after he has ceased to be visible.

Outside the screen — on the walls of the room in which the television is sitting — orange lights start to flicker. Briefly, there’s the shadow of a dark figure on the wall.

The screen — all of it; television and frame — goes black.

The credits roll.

Never Press The Rewind Button

The thing with “Teaching Jake About The Camcorder” is that, just as it has nesting narratives — the narrative in the room with the television and the VCR, and the narrative in the footage being played on the VCR, both of which also intersect into one greater narrative — it also has nesting challenges. It’s not a straightforward piece in any sense of the word, with most of what’s truly important happening below the surface. As such, it also offers two challenges to us as viewers — and because of those two challenges, the piece works on multiple levels.

On the one hand, “Teaching Jake About The Camcorder” challenges us first to figure out what, simply, the story is. Because there is a story; it’s not just a sequence of weird events.

What I take from it is that it’s the story of a family — specifically of a father and son — and a tragedy that tore them apart. We don’t know exactly what that tragedy was; whatever it was, though, we know it resulted in the father’s death, probably when he was still quite young, and quite possibly not too long after this video was recorded. We know this because of what happens in Loop 3: Dad looks at us — directly at us — and comments on how good it is to see us and how much we’ve grown. The way he says, “You’re an adult! Wow!” implies that he didn’t live long enough to see us actually grow to adulthood. This is new for him; he’s only ever seen us as a child — but now here we are, all grown up. Wow!

This idea is further supported by what Dad says to us in Loop 5: “Jake, I’m so thankful for the time we had together,” he says — and again, the implication is that we had some time together, but not the lifetime we, by rights, should have had. And when he continues — when Dad says, “But you can’t keep reliving it. That’s not going to bring me back” — he underlines the fact that he’s gone, that he’s been gone for some time, and that his absence is final.

Very little is more final than death.

That last line also tells us what our current situation is: Jake, years later, is still grieving, and struggling with that grief in a way that’s preventing him from truly processing it. It’s manifesting in the feverish, repeated watching and re-watching of this one particular home video — but what that watching and re-watching might be doing to him is… questionable. That’s why Dad, in multiple loops, urges Jake to stop watching the tape. This story is the story of how one person copes — or doesn’t cope — with their enormous, ever-growing sense of grief.

The interesting thing, of course, is that based on the way the film is shot, we — the viewers — are positioned as Jake. “Teaching Jake About The Camcorder” reads as if it’s being presented from a first-person perspective — and not just because the inherent nature of watching home movie footage puts us in the position of the person holding the camcorder. Here, we see it in how Dad sometimes speaks to us directly in the present — when he looks at us and observes how much we’ve grown, when he tells us he loves us, when he asks us to stop watching the tape — but also in how the outer frame works. The way we experience “Teaching Jake About The Camcorder,” we’re looking directly at the television — as if we’re sitting in front of it. We see a hand reach out, insert the tape, and press the play, stop, and rewind buttons — as if it’s ourownhand doing it.

That’s why I keep using the word “us”: We’re not just viewers. We’re Jake.

But there’s another level on which “Teaching Jake About The Camcorder” works: It not only challenges us to figure out what the story is, but also to figure out what it’s about. And if we take the VHS tape as the physical representation of a memory… well, it all makes a pretty solid statement about memory itself, as well as a warning about what happens if we allow ourselves to be consumed by it.

Guy Pearce’s Leonard Shelby perhaps put it best in the 2000 film Memento: “Memory’s not perfect; it’s not even good. … Memory can change the shape of a room; it can change the color of a car. And memories can be distorted. They’re just an interpretation — they’re not a record.” And this is true — not just a sound byte from an endlessly quotable movie. Research has found that, as the American Psychological Association put it in 2011, “we forget or falsely remember much more than we realize; we get facts wrong, for example, or misremember our reactions.” What’s more, our tendency to shape what happens to us into stories — to, essentially, become the storytellers of our lives — can affect how we remember certain events, The Conversation reported in in 2018.

That’s exactly what we see at work in “Teaching Jake About The Camcorder”: Each loop differs slightly in its overall details; each time we rewind the tape — that is, each time we recall the memory — something about it has changed, even if the overall arc of the memory is more or less the same.

Whether or not we can take the first loop as accurate — whether it present the scene as it actually occurred, rather than as a version of it distorted by memory — is unclear. I’m inclined to say yes, we can interpret it as such; it’s complete and uninterrupted, and provides us the general frame to which we’ll compare each successive loop.

But there’s danger in obsessively playing and replaying the same tape — in recalling the same memory— over and over and over again, too. And, in fact, “Teaching Jake About The Camcorder” tells us so right within the very first loop: It’s encompassed within the speech Dad gives us about the buttons on the camcorder.

Here, take another look at it:

“Okay. So — the only button you need to worry about is this red one right here. Don’t press it right now! That’s going to start and stop the recording — and never press the rewind button, or else you might record over a precious memory. All right? So, we always want to keep the recording going forward. Okay, bud? Okay. We can always just start a new tape.”

In this moment, Dad presents us with two extremely important instructions: Don’t press the rewind button, and always keep the recording going forwards. But in the present, we — Jake — don’t heed these warnings; we keep rewinding the tape, preventing the recording from advancing. Why is this a problem? Because with each rewind, the memory originally captured erodes a little bit. Did Dad have a full beard, or just a moustache? Was his hair swept to one side, or did it flop down over his forehead? Did I zoom in on his face, or on his sweatshirt? Did he say never to press the rewind button, or never, ever to press it?

It’s worth noting here, by the way, that we press the rewind button multiple times. In doing so, we corrupt the memory further each time we rewind it and play it back. In essence, we “record over a precious memory,” rewriting its details over and over and over again, with each successive viewing.

We’re also, in a way, destroying the memory. VHS tapes don’t last forever; that’s one of the reasons they’re now obsolete: They degrade with time.

VHS tapes of the variety we watch in “Teaching Jake About The Camcorder” are magnetic media. As NPR explained in 2017, magnetic tapes involve “sounds and images [being] magnetized onto strips of tape, using the same principle as when you rub a piece of metal with a magnet and it retains that magnetism.” However, when the magnet is removed, “the piece of metal slowly loses its magnetism — and in the same way, the tape slowly loses its magnetic properties.” Even when stored well — at room temperature in dry places away from humidity — VHS tapes can experience between 10 and 20 percent of signal loss from magnetic decay alone after about 10 to 25 years, per video-to-DVD transfer service V2DT. And that’s not taking into account things like water damage, issues caused by heat or cold, or even just general wear-and-tear on the tape itself.

Note, too, that the recording would have experienced a bit of what’s called generation loss, too, simply by the act of transferring it from the camcorder tape to the VHS tape: When data is copied or transferred to a different format, the data tends to suffer a little bit of degradation. The more times something is copied or transferred — the more generations of copying or transferring it’s gone through — the more degraded the data becomes.

So, here, we have a VHS tape with footage originally transferred from a camcorder which is being played and rewound and played again, repeatedly, several decades after it was first recorded. Each time we rewind and play the tape, we contribute to its decay — something which we can even see as each loop goes on. (Pay attention to Loop 4, for example; there’s a noticeable decline in the quality of the video that time ‘round.)

And, simultaneously, we’re refusing to allow the tape to continue playing forward — that is, we’re refusing to keep our life moving forward. We’re trapping ourselves in our memories, and unwittingly destroying those memories as we do so. We are both destroying the past and letting it destroy us.

This is what “Teaching Jake About The Camcorder” is about: Cherishing your memories, but not allowing them to consume you.

Always Keep The Recording Going Forward

There’s one mystery that I haven’t fully “solved,” so to speak: What the dark figure is, or what it represents. The easiest-to-reach-for explanation is that the figure represents Dad’s approaching mortality; or, if you want to get even more specific, it’s the force in his life that’s going to be responsible for his death. My brain went immediately to, “Oh, he’s ill — the figure is the illness creeping up on him, and ultimately, it will kill him.”

This interpretation is complicated a bit by the appearance of the figure’s silhouette on the wall of the room in which we, as Jake, are seated as we watch the tape right at the very end of the film. I suppose if it represents an illness, you can read it as something hereditary: The same illness that killed his father is lurking in Jake’s own life, too, and it’s coming for him no matter what he does. At the same time, though, you can also read this final appearance very differently — perhaps as an indication that our (Jake’s) obsession with reliving the past is about to result in our (his) imminent destruction. But then again, I’m not sure whether that interpretation holds up if we read Dad walking away at the end as us (Jake) coming to terms with needing to let go of the memory, and, well…

… All of this is to say that I think the mystery of the dark figure possibly doesn’t need to be definitively solved. We’re each going to take something different from it, making the experience of watching “Teaching Jake About The Camcorder” unique for each viewer.

And that, I suppose, is also why we, the viewers, are positioned as Jake in the first place: It lets the story of this film — and what the story is about — be… whatever each viewer needs it to be. Whatever is most significant for you. Whatever resonates the strongest for you. It’s all valid, and it’s all important.

Hold it steady.

Use both hands at all times.

Attaboy.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via brian david gilbert/YouTube (8)]