Previously: Phantom Social Workers.

At the beginning of August in 1885, a terrible storm descended upon the city of Chicago — a storm that dumped more than five inches of rain on the city in less than a day, overloading the sewer system and causing contaminated river water to wash into Lake Michigan. Given that Lake Michigan was where the city got its drinking water from, you can see how that would be a problem, right? And it was: Thanks to the contaminated water, a cholera epidemic hit Chicago in 1885 the likes of which had never been seen before. Some 90,000 people are said to have been killed by the disease during that single summer — a number that amounts to 12 percent of Chicago’s population at the time.

Except… it didn’t actually happen that way. There was a huge storm at the beginning of August 1885, and it did cause a lot of problems for Chicago — but a cholera epidemic isn’t one of them. As the Wikipedia page for the “cholera epidemic” notes, it’s a myth, an urban legend that has proven to be surprisingly resilient in the nearly century and a half since the storm struck. So how does such a huge myth about an epidemic that never happened actually start? In short, it seems to have been part of a sort of… propaganda campaign run in service of several public works projects undertaken in the city of Chicago during the latter half of the 20th century.

That’s right: The legend of the “cholera epidemic” only dates back to the 1950s, despite the storm that allegedly caused it having occurred during the 1880s.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

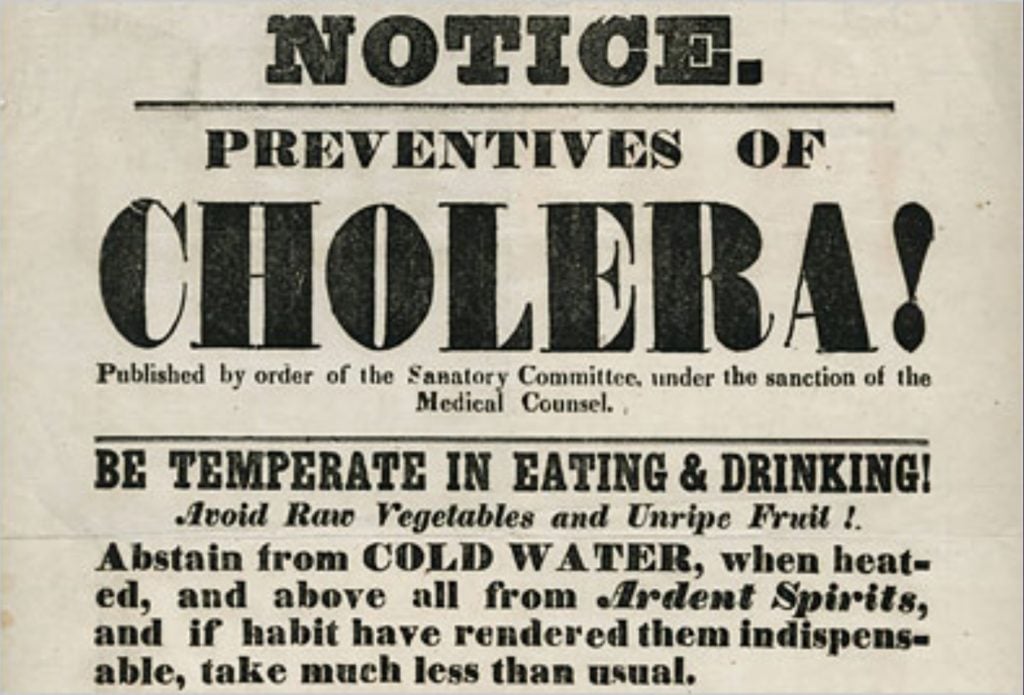

The earliest references to cholera date back to the fourth and fifth centuries B.C.E., according to writings by the Greek physician Hippocrates and the Sushruta Samhita in India. It’s not a pleasant illness; a bacterial infection, it both spreads and kills easily. And although it was tamed towards the end of the 19th century by the developments of immunization and the cholera vaccine, as well as the identification of the bacterium that actually causes the infection, it wreaked havoc worldwide throughout most of the 1800s.

And to be fair, Chicago did experience several cholera and typhoid epidemics during the mid-to-late 19th century that resulted in many deaths. In 1854, for example, cholera killed 1,424 citizens, while in 1891, typhoid was responsible for 2,000 deaths. However, as the Encyclopedia of Chicago points out, the city’s lowest point for these kinds of illnesses occurred in 1873. By 1885, when the devastating “cholera epidemic” caused by the August storm is meant to have occurred, Chicago’s struggles with the bacteria had largely ended. The Chicago River’s flow was also reversed soon after, finally carrying waste away from the city’s water supply, rather than toward it.

But there was no “cholera epidemic of 1885.” In fact, the very storm said to have caused the “epidemic” actually had the opposite effect, according to newspaper reports from the time. It totally cleared out the sewage system — and although the storm did cause polluted river water to make its way into Lake Michigan, the winds changed shortly thereafter in such a way to sweep it all away from the water intakes, keeping the drinking water unexpectedly clean and lowering the death rate. “On the last of July we were about as dirty a city as there was north of the Ohio River, and our death rate was the highest of any large city in the country,” wrote the Chicago Daily News on Aug. 17, 1885. “On the 3rd of August we were undoubtedly the cleanest city on the continent externally, and since then our death rate has been the lowest of any large city probably in the world.”

Beginning in the 1950s, though, the myth has been repeated as fact time and time again, often by reputable news sources buying into the tale. How did those who started the legend hoodwink everyone so well and for so long? Well… it seems that some folks will say anything to get what they want. Especially when “what they want” are giant and costly construction projects.

Further Reading:

“Did 90,000 People Die Of Typhoid Fever And Cholera In Chicago In 1885?” at Straight Dope. For a quick overview separating fact from fiction, this piece from Straight Dope should do the trick. If you want the full details, though, you’ll have to go to Straight Dope’s main source: Libby Hill.

On that note…

The Chicago River: A Natural And Unnatural History by Libby Hill. Originally published in 2000 and revised in 2019, Hill’s book is one of the most thorough documentations of the history of both the city of Chicago and the Chicago River — two entities which are impossible to separate. As Hill put it herself, “Chicago created the river just as surely as the river was the genesis for Chicago.” The Chicago River is just one of the works Hill has written over the years that includes a debunking of the myth, but it’s one of the most readily accessible and complete, so definitely check it out.

Hill found that, although cholera was initially a concern in the aftermath of the storm, absolutely no reports from the time mentioned anything about a full-on epidemic, let alone one that killed 90,000 people. Remember, 90,000 people was a whopping 12 percent of Chicago’s population — so an epidemic that supposedly killed that many people would absolutely have been newsworthy. And yet, there’s nothing.

But even if the storm didn’t result in illness that killed 90,000 people, it did “jolt bureaucrats into action,” according to Hill, which got several much-needed public works projects geared towards keeping the drinking water in Chicago clean off the ground. So, y’know, at least there’s that.

The revised edition of the book is here.

“And A Flood Came” in the Chicago Tribune, Aug. 3, 1885 edition. A piece in the Chicago Tribune reporting on the Aug. 2, 1885 storm that’s usually cited as the instigating event of the mythical cholera epidemic. The storm was pretty wild; 5.58 inches of rain fell on the city in just 19 hours, which the report called “almost unprecedented”: Up until that point, the heaviest storm of the season so far had only resulted in a fall of 3.44 inches. Basements flooded, stock in stores and restaurants was ruined, fires started, and large scale destruction ruled. More than anything else, though, the storm demonstrated that Chicago’s sewage system was “entirely inadequate” for the level of rain the city received.

Epidemics That Did Hit Chicago In The 1800s at the Encyclopedia Of Chicago. A rundown of all the actual epidemics that caused trouble in Chicago during the 1800s, including but not limited to cholera, scarlet fever, whooping cough, typhoid, smallpox, and more. It provides useful context for how a myth like that of the 1885 “cholera epidemic” might find legs.

“The Making Of An Urban Legend” by Libby Hill, the Chicago Tribune, 2007. Libby Hill also discussed the origins and evolution of the “cholera epidemic” myth in a piece for the Chicago Tribune in 2007. Although the concerns addressed by the legend — contaminated drinking water in the aftermath of the storm, cholera, and typhoid fever — were initially anticipated in news reports immediately following the storm, as previously noted, a surprising turn of events prevented those concerns from becoming a reality (this time around, at least). But in the 1950s, the Metropolitan Sanitary District — now the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District — incorporated the 1885 storm into its campaign to build support for a flood control project.

The project emerged out of a 1954 storm that dumped the most water the city had seen on Chicago since the 1885 storm — six inches this time. So, the publicity campaign for the flood control project used the previous storm as a scare tactic: A 1956 pamphlet, for example, insisted that “death from the terrible diseases of polluted water” were “one byproduct of the [1885] storm,” even though the historical record doesn’t support that assertion. The 1885 “epidemic” was continually invoked over the next few decades, including during the push for and continued coverage of what became colloquially known as the Deep Tunnel project (see below). With each new repetition, the myth gained legitimacy it didn’t actually possess, and, well… here we are now. What a weird, weird world we live in.

The Deep Tunnel Project. Here’s more about said Deep Tunnel Project, which “aimed to reduce flooding in the metropolitan Chicago area, and to reduce the harmful effects of flushing raw sewage into Lake Michigan by diverting storm water and sewage into temporary holding reservoirs,” per the website Old Time Photos. Has it been successful? Well… not entirely, according to a piece published at Slate earlier in 2019. Click through for more.

“Chicago’s Legendary Epidemic” in the Chicago Tribune, Aug. 22, 2007. The Tribune’s piece setting the record straight, including the acknowledgement of several articles published by the paper over the years that erroneously referenced the “epidemic” as fact. “We could attribute the legend’s long life and frequent repetition to a decidedly un-Chicago trait: gullibility,” wrote the Tribune. “We’d rather, though, characterize this as a case of facts getting in the way of a good story. Less embarrassing that way.”

But cholera is still no laughing matter. Consider:

An Overview of Cholera from the Mayo Clinic. Caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae and spread through contaminated water, cholera severely dehydrates its sufferers, with symptoms including diarrhea and vomiting, as well as lethargy, dry mouth, low blood pressure, and arrhythmia. It’s easily treated, but still often fatal, particularly in areas stricken by poverty, war, and/or natural disasters.

The World Health Organization’s Fact Sheet On Cholera. Facts on cholera in our current world. It’s not a pretty picture; researchers estimate that there are between 1.3 and 4 million cases of cholera every year, with anywhere between 21,000 to 143,000 deaths resulting from the infection — despite the fact that it’s both treatable and preventable.

Cholera Outbreaks And Pandemics on Wikipedia. An overview of the seven cholera pandemics we’ve seen throughout human history, with links to more in-depth Wiki articles on each one. The first cholera epidemic began in 1817 near Calcutta and killed some 100,000 people; the seventh began in 1961 in Indonesia and is still ongoing as of 2019. We might know how to prevent and treat it now, but cholera remains a huge concern in developing countries, where easy access to clean water is far from a given.

Annals of Cholera: From the Earliest Periods to the Year 1817 by John Macpherson. A history of cholera prior to the first epidemic in 1817, published in 1872 by Ranken and Co., Drury House. It’s here that we can find details of Hippocrates’ early mentions of the disease, although we’re limited to case-by-case descriptions of specific cases, rather than a systemic description. He chalked it up to “disordered bile” — that is, he connected it to the four humors theory of medicine, which posited that both your personality and health were a result of how balanced four substances believed at the time to exist in the human body were in you, specifically. Feeling melancholic? You’ve got too much black bile in your system. Feeling sanguine? Too much blood. Phlegmatic? Too much phlegm, of course. And choleric? Too much yellow bile. Head to chapter three of the book for more.

The 2010 Haiti Cholera Outbreak. Here’s why the Chicago cholera epidemic myth isn’t so hard to believe: An actual epidemic of similar magnitude has been going on in Haiti since 2010.

After a massive earthquake hit Haiti in January of 2010, U.N. troops deployed from Nepal were among those who arrived in the aftermath and are now believed to have carried in the strain of cholera that has subsequently sickened hundreds of thousands of people — close to a million, in fact — and killed more than 9,000. This outbreak is generally thought to be the first large-scale outbreak of the disease in modern history. As of 2018, the U.N. has not accepted responsibility for the outbreak, and although the organization pledged $400 million to assist affected Haitians, only $8.7 million — 2.2 percent of the $400 million promised — has been raised, and less than half of the raised amount spent, according to Reuters.

The illness is deadly. It’s still a problem. And not nearly enough is being done about it.

It’s not always a myth, you see.

Don’t be fooled into thinking it is.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photo via Wikimedia Commons, available in the public domain.]

Leave a Reply