Previously: Dowsing And The Power Of Expectation.

We’ve all seen scenes in movies or read about them in books where someone drifts off, daydreaming, only look down and find they’ve written or drawn something horrifying, right? Automatic writing, as it’s called, is all over horror fiction, whether we’re talking about period pieces or contemporary stories. These stories don’t always explain how automatic writing works, though — and, as it turns out, what the deal is depends a lot on your own point of view.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

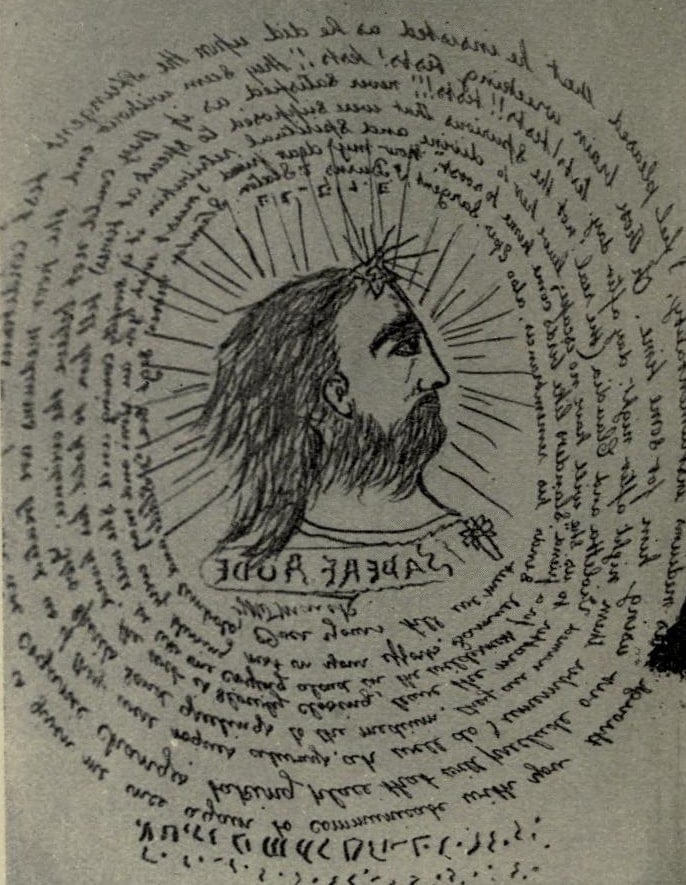

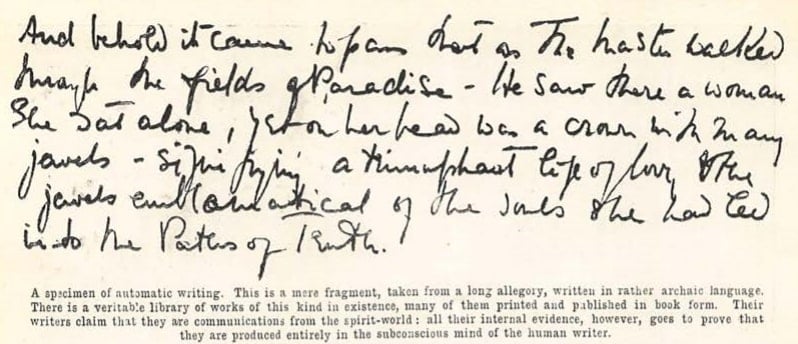

Also known as psychography, spirit writing, and trance writing, automatic writing is closely associated with the Spiritualist movement of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Loosely defined, it’s “a type of divination where the pen appears to direct the writer instead of the writer directing the pen,” according to the Paranormal Encyclopedia; however, it’s most popularly understood as a mean through which spirits can communicate with the corporeal world. It isn’t limited to just words, by the way; pictures, shapes, or even just doodles are said to be significant by those who believe in the practice. (In fact, the medium I spoke with when I spent the night at a haunted house last fall routinely does what she calls “doodling” throughout readings.)

But not everyone believes in it, of course — so the mechanism by which it functions varies depending on who you talk to. We’re going to take a look at both sides of the aisle; first, though, a history lesson: Let’s take a look at the origins of automatic writing.

A Brief History Of Automatic Writing

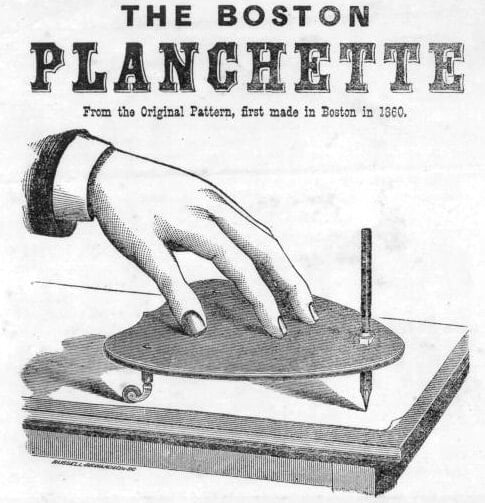

It’s unclear precisely how long automatic writing has been in practice, but one of the earliest precursors dates back to the Liu Sung or Liu Song dynasty in China — a period which spanned the years 420 to 479 CE. We talked about this when we took a look at the history of the Ouija board, but in case you need a refresher, the form of divination known as fu chi or fuji spirit writing involved creating a type of planchette by attaching a sieve to a short stick. Two people would hold the device over a pile of sand or ashes while the stick traced out characters in the dust — the characters believed to be messages from the gods. Fu chi and this type of planchette would be further developed during the Tang and Ming dynasties, which ran from 618 to 907 CE and 1368 to 1644 CE, respectively.

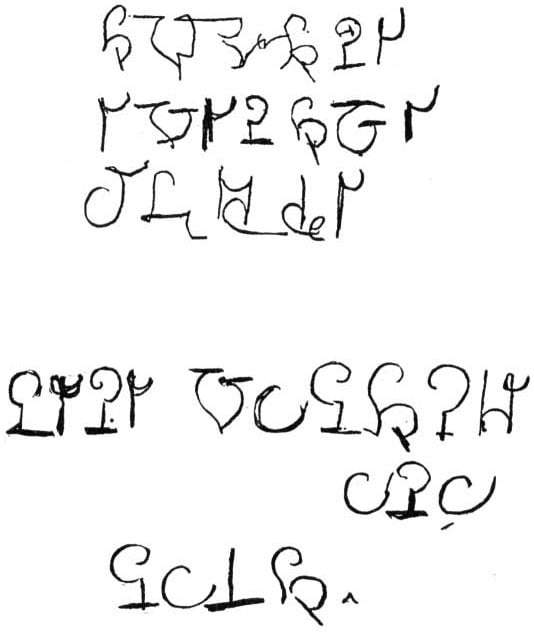

In the West, the discovery (or development, depending on your point of view) of the Enochian language by John Dee and Edward Kelley in England in the 16th century is considered to be an early example of automatic writing. Dee, a mathematician, scientist, alchemist, and occult philosopher, was an advisor to Queen Elizabeth I; often referred to as a magician, he may have served as the inspiration for both Faustus in Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus and Prospero in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Kelley, meanwhile, was an occultist and self-identified spirit medium. The two joined up in the early 1580s, with Kelley becoming Dee’s regular scryer./ (Kelley’s preferred tools were typically mirrors and crystals — “shew-stones,” in the parlance of the day.) Together, they would produce the works that outlined what’s known as Enochian magic — a system of magic they said was dictated to them by angelic beings.

In March of 1853, during one Kelley and Dee’s standard angelic conferences, Kelley reportedly began having visions of an alphabet with which he wasn’t familiar; then, in another session shortly thereafter, he received the first piece of text writing using this alphabet.

To be clear, Kelley and Dee’s experience wasn’t quite an instance automatic writing as it would later grow to be understood; Dee didn’t hold pencil or planchette and perform the writing himself. Rather, the duo functioned as a team, with Kelley receiving the messages through his shew-stone and Dee transcribing what Kelley dictated to him. As the blog Skepsisartikler sums it up:

“To begin with, Kelley had visions of great square tables, each with 49 x 49 squares. The instructions from the angels were that these tables should be filled with letters forming words. According to John Dee’s transcription of this incident, it seems like Kelley would report ‘seeing’ the text that made out the horizontal lines of the tables, and then read them aloud to Dee: ‘Palce duxma ge na dem oh elog …’ The texts that resulted from these actions in spring 1583 constitute the first of two groups in the very limited Enochian text corpus, termed by Dee Liber Logaeth, ‘speech from God.’”

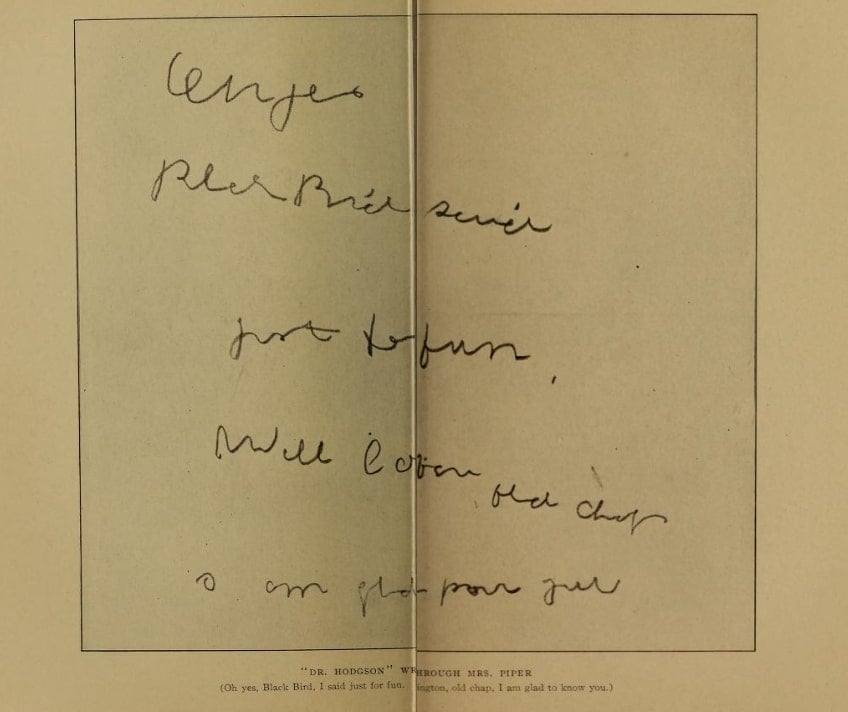

It was during the 19th century, though, that automatic writing truly began to flourish, particularly in North America and Europe. When the Spiritualist movement began, kicked off largely by the Fox sisters’ 1848 claim that they had contacted the spirit of a peddler who had been murdered in their family’s house in Hydesville, New York, séances, divination, and spirit mediums became all the rage — and automatic writing became one of the most commonly-used methods of otherworldly communication. Noted mediums such as Leonora Piper, Pearl Curran, Helene Smith, William Stainton Moses, and Helen and Margaret Verrall utilized automatic writing with some regularity. Psychical research about automatic writing also began to kick up around this time, featuring in the works of Frederic W. H. Myers, Edmund Gurney, Morton Prince, and many others.

A séance conducted during this era would typically begin with the gathering of a group of people and a medium in a darkened room, typically seated at a table. The participants might hold hands, or they might not. After appropriately setting the mood, the medium would go into a trance, at which point the main event would occur: Rapping, table-tilting, bell-ringing, ectoplasm, possession, and automatic writing were all on the table as possibilities (literally). Both social events and religious ones, séances “brought people together,” as musician Jill Tracy of the musical improv show The Musical Séance told Collector’s Weekly in 2014. Continued Tracy:

“It enabled them to face their fears because it was being pitched to them as a form of group amusement, instead of a frightening experience where one sits in their house alone and tries to talk to a spirit. A séance was also sensually charged, the true definition of arousing the senses. Men and women would sit in the dark in close contact, often holding hands or touching, and they would have no idea what was going to happen. For Victorians, it was almost an acceptable moment of abandon.”

Although Spiritualism began to drop in popularity after the 1920s, it’s still practiced today; in fact, it split into three different factions, many of which have their own churches. Automatic writing, too, may have fallen in popularity somewhat, but still has its devotees across the globe; indeed, as Ian Stevenson observed in his paper “Some Comments On Automatic Writing,” which was published in the Journal Of The American Society For Psychical Research in 1978, “Waves of popular enthusiasm for automatic writing occur in irregular cycles.”

So, how does automatic writing work? As always, there are two arguments to be made: The believer’s argument and the skeptic’s. Let’s take a look at them both in turn.

The Believer’s Argument

Automatic writing is simple in practice: All you need to do is go to a quiet room, sit down at a desk or table with a piece of paper and a pen or pencil held loosely in your writing hand, relax and clear your mind, and let your hand write or draw whatever it feels like. Before the advent of the talking board or Ouija board, planchettes fitted with wheels and writing tools were also commonly used, both by individuals and by groups. But like many forms of divination, not everyone who believes in automatic writing is in agreement about exactly what’s going on during a session.

on, not everyone who believes in automatic writing is in agreement about exactly what’s going on during a session.

Automatic writing falls under the larger umbrella of automatism, or what psychical researcher Frederic W. H. Myers defined in his posthumously published work Human Personality And Its Survival Of Bodily Death (1903) as “mental images arising and movements made without the initiation, and generally without the concurrence, of conscious thought and will.” Myers described two kinds of automatism: Sensory automatism, which typically includes visual and/or auditory hallucinations, and motor automatism, which includes “messages written and words uttered without intention (automatic script, trance-utterance, etc.).” As a form of motor automatism, automatic writing, Myers wrote, could emerge from one of five sources: “Conscious will, unconscious cerebration, a higher faculty of one’s own mind, telepathic contact with other incarnate minds, [or] discarnate spirits and extra human intelligences,” per the Psi Encyclopedia.

These days, there are a few schools of thought when it comes to exactly how automatic writing works. In one, the spirit function as an external source of movement from the medium: That is, the spirit moves or manipulates either the medium’s hand or the pen or pencil itself to form the writing — kind of like when adults place their own hands over children’s when they’re learning to write in order to guide them and help them form the letters. In another, the spirit places messages directly within the mind of the medium, which the medium then communicates to other through the use of pen and paper — that is, the medium is basically transcribing messages imparted to them by the spirit. In another, the spirit literally possesses the medium, superseding the medium’s own personality and driving their body like a car for a time. And in a fourth, as Troy Taylor puts it at The Haunted Museum (formerly known as Prairie Ghosts), “the medium is writing unconsciously and messages are formed from material in the subconscious mind or from a secondary personality that is gifted with extrasensory perception” — that is, the medium displays a second personality that isn’t the result of possession by an outside force, but one which they already hold deep within themselves.

There’s some debate over whether a medium can be aware of what they’re doing while automatic writing or whether they must necessarily sort of disassociated from themselves. Some even believe it might be a mix of the two — as Ian Stevenson wrote in “Some Comments On Automatic Writing”:

“The term ‘automatic writing’ is used to designate writing that is done without the writer being conscious of what [they are] writing, or even (occasionally) the act of writing. Perhaps I should say ‘fully conscious’ because automatic writers may have some awareness of what they are writing as they write.”

Further, in the 1992 paper “Skirting The Abyss :A History Of Experimental Explorations Of Automatic Writing In Psychology,” published in the Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, Wilma Koutstaal detailed a number of experiments conducted during the height of the Spiritualist movement in which the hand of an automatic writer was determined to have necessarily been “in sensorial connection” with the “personality” thought to be producing the writing.

It’s interesting to note that, either way, the different schools of thought ca explain why the actual style of handwriting might differ from session to session and from medium to medium. If the spirit is moving the medium’s hand or the pen or pencil, for example, or if they’ve straight-up possessed the medium, the handwriting might look totally different from the medium’s own. However, if the medium is functioning more like a transcriber, the handwriting might simply appear to be their own.

But no matter what folks think is actually going on — which, by the way, may not necessarily be the same from medium to medium — what believers in automatic writing are certain of is the power of the technique to bring forth messages we might miss otherwise — messages from a realm beyond our own.

Skeptics? Not so much.

The Skeptic’s Argument

Most skeptics chalk the results of an automatic writing session up to something that should be familiar to regular readers of TGIMM’s “How Does It Work?” feature: Our old friend, the ideomotor effect.

We’ve discussed this well-documented phenomenon a number of times; it’s come up in both our examination of the Ouija board and our look at dowsing. As a reminder, the ideomotor effect comprises “unconscious, involuntary motor movements” which are “performed by a person because of prior expectations, suggestions, or preconceptions,” per the Critical Thinking Association. In the case of the Ouija board, these movements push the planchette to indicate the answers to our questions which we already know, deep down inside. In the case of dowsing, the dowsing rods indicate where we unconsciously believe we’re likely to find what we’re looking for. And in the case of automatic writing, we write or draw ideas or images we already have hidden somewhere in our brains.

I think it’s interesting, by the way, that William Benjamin Carpenter first observed the ideomotor effect in 1852 — right around the same time that Spiritualism was really starting to take off.

However, as David Derbyshire pointed out at the Guardian in 2013, psychologist Dan Wegner, who did a lot of work on the rebound effect — that phenomenon wherein, if you tell someone not to think about a specific thing, they’ll be able to think of nothing but that thing — before his death in July of 2013 had another idea: That, rather than being born out of the subconscious mind, automatic writing came from “the illusion of free will.”

“Wegner’s solution was that our deliberate, thinking brain —the inner me that makes decisions — is an illusion. Instead, the brain does two things when it makes a decision to raise an arm. First it passes a message to the part in charge of creating the conscious inner you. Second, it delays the signal going to the arm by a fraction of a second. This delay generates the illusion that the conscious mind has made a decision.

“Wegner argued that automatic writing occurs when something goes wrong with this process. The brain sends the signal to the arm to write — but fails to alert the inner you.”

Here, automatic writing isn’t even a psychological thing — it’s physiological.

And, of course, there’s always the possibility that those who claim to be able to contact spirits through automatic writing are hoaxers.

Many, many mediums and other spiritual “experts” working freely during the heyday of the Spiritualist movement were eventually revealed as frauds: Maggie Fox spoke publicly in 1888 of the tricks she and her sister, Kate, had employed to create the rapping sounds they had once said were the work of spirits. William H. Mumler’s ghost photographs were found to be accomplished by in-camera editing techniques like double exposures; he was put on trial for fraud in 1869, and although he was acquitted, his career and reputation never pulled up from the nosedive they experienced as a result of the court case. And slate writing — a common technique used to produce spirit writing — was found to be nothing more than a trick, as well.

Obviously not everyone who says they can perform automatic writing is lying; some might be, though. Even if you believe in it, you might still want to be careful taking everything at face value.

What Do You Believe?

Folks fall on either side of the argument, and generally speaking, it’s hard to convince someone with firmly held beliefs that there might be others worth considering. But here’s the thought I’d like to leave you with:

The neat thing about the ideomotor effect is that, even if it’s not necessarily producing messages from straight-up ghosts, there is still something a little magically spooky about it. It’s kind of like a window into your deepest thoughts and feelings — the ones you’ve buried so far down that you aren’t even aware they belong to you. Automatic writing, Ouija boards, and other alleged psychic phenomena that can be explained by the ideomotor effect all bring those thoughts and feelings out into the open, where you can look at them clearly — maybe for the first time ever.

The ghost isn’t a ghost at all.

The ghost is you.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via Wikimedia Commons (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6), available via public domain.]

Leave a Reply