Previously: Spirit Boxes And Auditory Pareidolia.

Weirdly enough, the first time I encountered the concept of dowsing was in a manga I first read about 20 years ago — and I say “weirdly” because dowsing is very much not a traditionally Japanese form of divination. The manga (which, for the curious, was the third case in the Kindaichi Case Files series) featured a character who was meant to be a dowsing expert — and upon reading her demonstration of the practice, all I could think was, “That’s it? But… how does dowsing work?” I couldn’t quite wrap my brain around the idea that anyone could do it as long as they had a stick or two handy — and that it would likely see a certain amount of success.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

A method of divination used most frequently to locate sources of groundwater or mineral deposits, dowsing dates back quite ways — although possibly not as far back as many actually think it does. It’s a distinct looking process; if you’ve ever seen anyone (or video footage of anyway) walking around an outdoor space holding either a Y-shaped tree branch or two metal rods out in front of them, you’ve witnessed someone dowsing. The idea is that these tools can indicate the presence of something unseen. But although dowsing is usually thought of in conjunction with finding water (that’s why one of its alternate names is “water witching”), contemporary dowers might use it to locate any number of things — from lost items to missing people.

And, as you might expect, there’s more to the whole thing than meets the eye. Let’s take a closer look, shall wee?

A Brief History Of Dowsing

George Casely dowsing on his farm in Devon, England in 1942.

There’s some evidence suggesting that dowsing goes back to ancient times; as Lois Parshley pointed out at Aeon in 2015, the earliest known reference to the practice is thought to be a cave painting at Tassili n’Ajjer in the Sahara Desert that dates back to around 6000 BCE. However, dowsing as we know it today — that is, as a means of finding water or mineral deposits — didn’t come into vogue until the Middle Ages in Europe. (Most of the ancient references we have to “divining rods” and the like speak more broadly to rhabdomancy, which is a sort of umbrella term that covers any form of divination using sticks or rods.) By the time the Protestant Reformation rolled around, dowsing was both well-established and beginning to see some pushback.

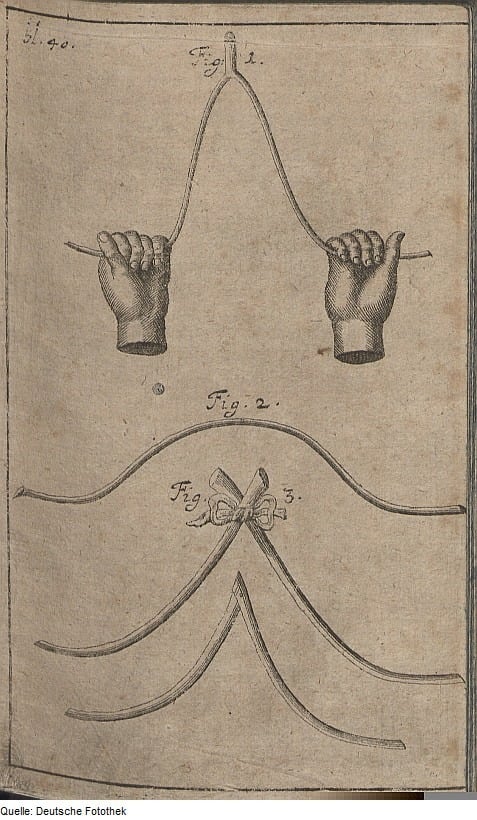

The first known source documenting dowsing specifically as a means of finding water and minerals is De Re Metallica, a landmark work on mining by German mineralogist and metallurgist Georg Bauer writing under the Latinized name Georgius Agricola, which was first published in Latin in 1556.Indeed, according to a footnote in the 1950 edition of De Re Metallica published by Dover Publications — originally translated into English and annotated by Herbert Clark Hoover and Lou Henry Hoover in 1912 — Agricola’s section on dowsing is, “so far as we are able to discover … the first published description of the divining rod applied to minerals or water.” (The Hoovers do cite several other works citing it that were likely written before Agricola’s, but none of them were actually published until sometime later.)

Here’s how Agricola described the process of dowsing:

“There are many great contentions between miners concerning the forked twig, for some say that it is of the greatest use in discovering veins, and others deny it. Some of those who manipulate and use the twig, first cut a fork from a hazel bush with a knife, for this bush they consider more efficacious than any other for revealing the veins, especially if the hazel bush grows above a vein. Others use a different kind of twig for each metal. … All alike grasp the forks of the twig with their hands, clenching their fists, it being necessary that the clenched fingers should be held toward the sky in order that the twig should be raised at that end where the two branches meet. Then they wander hither and thither at random through mountainous regions. It is said that the moment they place their feet on a vein the twig immediately turns and twists, and so by its action discloses the vein; when they move their feet again and go away from that spot the twig becomes once more immobile.”

However, we also know that dowsing was a well-known practice some decades before the publication of De Re Metallica. Martin Luther spoke out about it in the early 16th century, first in sermons and then in his 1518 work Decem Praecepta Wittenbergensi Populo Praedicta. Per Luther, “he who in his tribulation seeks the help of sorcery, black art, or Witchcraft”; “he who uses letters, signs, herbs, words, charms and the like”; and “he who uses divining-rods and incantations, and practices crystal-gazing, cloak-riding, and milk-stealing” breaks the First Commandment, which states, “thou shalt have no other gods.”

But despite Luther’s opposition, the practice of dowsing as described in De Re Metallica spread rapidly throughout Europe, particularly in mining communities — and its uses expanded as it went. In 1692, Jacques Aymar helped solve a robbery and murder in Lyon, France by, he claimed, using a Y-shaped divining rod to locate the perpetrator of the crime. Homesteaders in the American West dowsed to find the best places to create wells during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1967 during the Vietnam War, Marine Corp engineers used “coat-hanger dowers … to detect tunnels, mines, and booby traps,” according to the New York Times Magazine via Aeon. These days, people might use dowsing to locate everything from lost keys to lost people.

Still, though, the identification of groundwater remains one of dowsing’s most popular uses — so much so that, in 2017, a somewhat shocking number of water companies in the UK confirmed to science writer Sally Le Page that some of their technicians sometimes use dowsing to locate water pipes or leaks.

So: How does dowsing work? As you might expect, there are two schools of thought here. Let’s take a look at both:

The Believer’s Argument

According to those who believe in it, dowsing can be accomplished with the aid of a number of different tools. A forked stick that forms the shape of a Y is one of the most common; if you hold the two ends of the forked section in your hands with the stem of the Y pointing forward and walk around an outdoor area—what’s termed “field dowsing” — the stem is said to point downward when there’s water or a mineral vein present. Some dowsers who use this method prefer the sticks to come from specific varieties of trees — witch hazel is widely used, for example, and according to Agricola, whose 1556 description of dowsing details the use of the forked stick, the type of wood used will indicate different substances. These days, Y-rods made of metal may also be used for dowsing; instead of cutting these rods from a tree yourself, though, you’ll typically have to buy them.

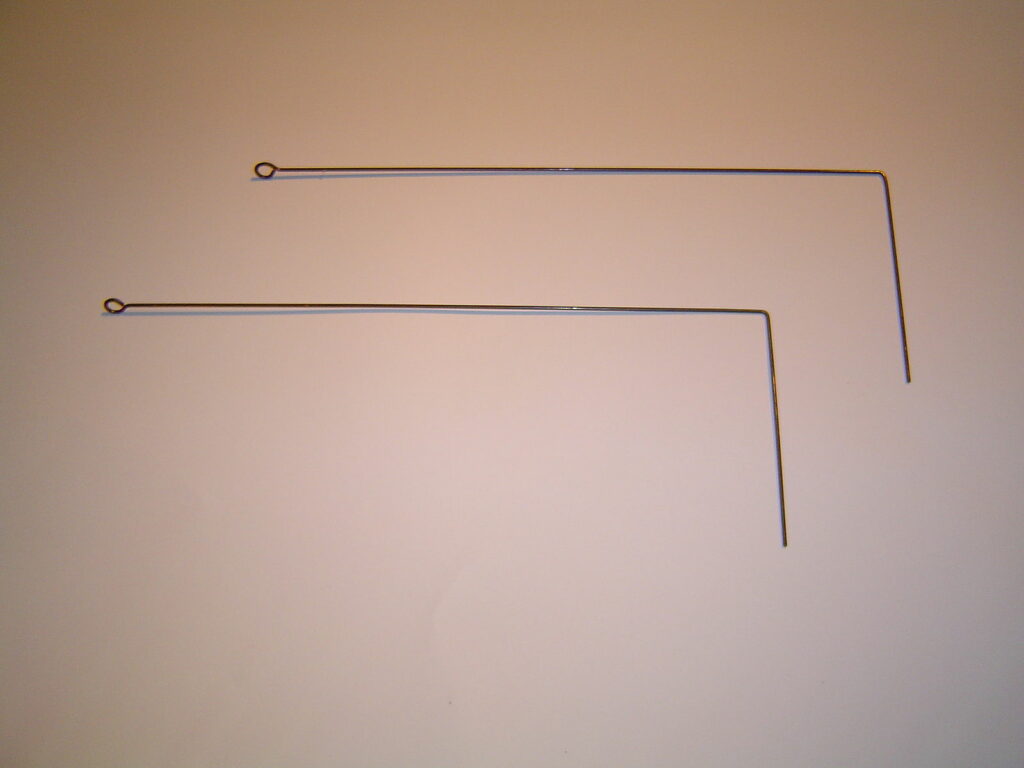

L-rods, meanwhile, are used in pairs: The dowser holds an L-shaped metal rod in each hand, grasping them by the short leg of the L and pointing the long leg forward, and walks around an area the same way you would while using the forked stick method. When you come across a water source or mineral deposit, the long legs of the L are said to cross. You can buy specially made L-rods specifically meant to be used in dowsing — but you can also just make a set yourself with an old coat hanger or any spare wire you might have hanging around.

Then there’s pendulum dowsing, in which the dowser carries an item hung at the end of a string — often a crystal, but not necessarily so — and watches how the pendulum swings in order to determine whether there’s water or minerals present in a given spot. If it swings back and forth, there’s nothing there; however, if it swings in a circle or ellipse, that’s an indication that there’s something worth digging for. (Pendulum dowsing can also be used as an informational divination method — if you ask it yes or no questions, its movements will reportedly reveal the answers to you.) Again, you can buy pendulums made for dowsing if you like, or you can make one yourself.

Finally, there are dowsing bobbers — flexible wires with a handle at one end and a wooden bead at the other. The bead adds weight to the far end, allowing the wire to bob about freely when you hold the other end by the handle. Using and reader a bobber is much like using and reading a pendulum; its motion can indicate either answers to yes or no questions or the presence of water or minerals. Again, you can either make or buy a bobber. Both pendulums and bobbers can be calibrated or “programmed” by the dowser; at the beginning of session, simply ask the device to perform specific movements for particular answers. Doing so might make reading the device’s responses easier, according to those practiced in using the tools.

Note, by the way, that most of these tools and methods can be used for “map dowsing” as well as field dowsing or informational dowsing. To do so, hold your tool of choice over a map; the device should indicate where on the map something like water might be found.

So, the “how” for dowsing is an easy question to answer: You pick up a certain tool, you walk around with it or ask questions of it, and when there’s something present for it to respond to, it indicates to you what and where that something is. The “why,” though, is a bit harder to answer — and not unlike, say, spirit boxes, there isn’t really a consensus on exactly why the devices respond as they do.

According to some believers, dowsing is an example of radiesthesia — a special “feeling” one might get about the presence of water or whatever else you’re looking for which is amplified by the dowsing tool. In this sense, as the online myth and folklore encyclopedia The Mystica puts it, “It appears to be more like a psychic medium, nearer to … ESP than contemporary physics.” According to others, the presence of water or other objects gives off some kind of “radiation” or produces an electromagnetic field, which in turn affects the dowsing tool and causes it to move. And others are simply uninterested in why dowsing works; they only know that it does, and that’s all that matters to them. In this view, it’s a question of faith.

The Skeptic’s Argument

The interesting thing about dowsing is that most people are generally in agreement that the rods, sticks, and pendulums do move. The disagreement is over what causes the movement — and according to the skeptics, that cause is something we’ve talked about here at TGIMM before: The ideomotor effect. You know — the thing that skeptics believe makes the planchette on a Ouija board move.

I’ll send you over to our “How Does It Work?” piece about the Ouija board for a more detailed rundown of this phenomenon, but in case you need a refresher, here’s the short version: The ideomotor effect was first observed in the early 1800s before being formally identified in 1852 by physician William Benjamin Carpenter. It describes the unconscious and/or involuntary movements our bodies and muscles can make, often because we have preconceived notions or biases that primes us to make those movements and interpret them in certain ways. In the case of the Ouija board, it can result in us spelling out answers to our own questions with the planchette — answers we may already know, deep down in our souls or brains, but which we find easier to access if we’re attributing it to some sort of higher power.

When it comes to dowsing, it’s even easier to see how the ideomotor effect might play out. If we’re expecting to find something somewhere, our muscles might involuntarily perform movements that will cause our dowsing rods to indicate that something’s presence. In the case of lost objects, it might be an instance of our subconscious recalling where the last place we saw that object was. In the case of water, it might be our brains unconsciously picking up cues in the environment that indicate groundwater might be nearby — combined with the fact that, if you dig deep enough in most places, you’re statistically likely to hit water at some point. Voila: Dowsing “success.”

Even the miners Agricola wrote about in 1556 were likely falling prey to the ideomotor effect: As Benjamin Radford pointed out in a 2016 Q&A published at the Center of Inquiry’s website, Agricola’s conclusion wasn’t that dowsing worked; it was it was, at best, unnecessary. Agricola chalked up the practice’s successes as pure accident. Any miner worth their salt shouldn’t require dowsing to find a vein, he wrote — they should simply be able to recognize one for what it is by dint of being an expert in the matter:

“Therefore a miner, since we think he ought to be a good and serious man, should not make use of an enchanted twig, because if he is prudent and skilled in the natural signs, he understands that a forked stick is of no use to him, for as I have said before, there are the natural indications of the veins which he can see for himself without the help of twigs.”

It’s also of course worth noting that although there’s a lot of anecdotal evidence that dowsing “works” to some extent, the same “successful” results have never been achieved under laboratory conditions. As Sally LePage put it in her piece on dowsing and UK water companies in 2017, “Every properly conducted scientific test of water dowsing has found it no better than chance. … You’ll be just as likely to find water by going out and taking a good guess as you will by walking around with divining rods.” Studies LePage pointed to here include this one, this one, and this one.

That last one might look like a positive result at first, but as a new analysis of the data published in 1999 in the Skeptical Inquirer highlighted, the “best” dowsers indicated by the researchers of the original study actually weren’t that accurate after all; they could only be seen as such if you ignored all the times they were wrong. Noted the new analysis, “All six of the ‘best’ dowsers would have done better on average by making mid-line guesses than achieved by actual dowsing, in terms of the root-mean-square error, a commonly used index of reliability (similar to the standard deviation).”

What Do You Believe?

1935.

Where do you stand? Do you think it works? Have you seen it work? Have you actually made it work yourself? Or do you think it’s more likely our brains and bodies working in unconscious ways — or maybe simply chance or luck to which special meaning is erroneously attributed?

Myself? To be honest, I’m not sure what I believe. Unlike the previous two topics we’ve covered in this “How Does It Work?” feature, I’ve never actually attempt to perform dowsing myself — and without any personal experience, I’m having a hard time doing anything with it other than thinking about it conceptually. The skeptic in me thinks that it’s… well, not a hoax exactly; as Benjamin Radford put it at the Center for Inquiry, it’s not so much that it’s “intentional deception,” but that it seems like it could be “a form of self-deception that often convinces others.” But it is curious to me that no one really doubts that the dowsing rods and tools do move — and even more curious that there’s so many demonstrable, true stories of people using dowsing to locate water or other objects.

It’s the kind of grey area that makes me want to go out and try it for myself. Just, y’know… to see.

Maybe I’ll do that.

Just, y’know, not now. It’s February, and I live in the northeast. It’s cold.

But it’ll start warming up in a month or two.

And then? Well, I do have plenty of spare wire lying around the house…

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via Wikimedia Commons (1, 2, 3, 4, 5), available under a Creative Commons license or in the public domain.]