Previously: Unfavorable Semicircle.

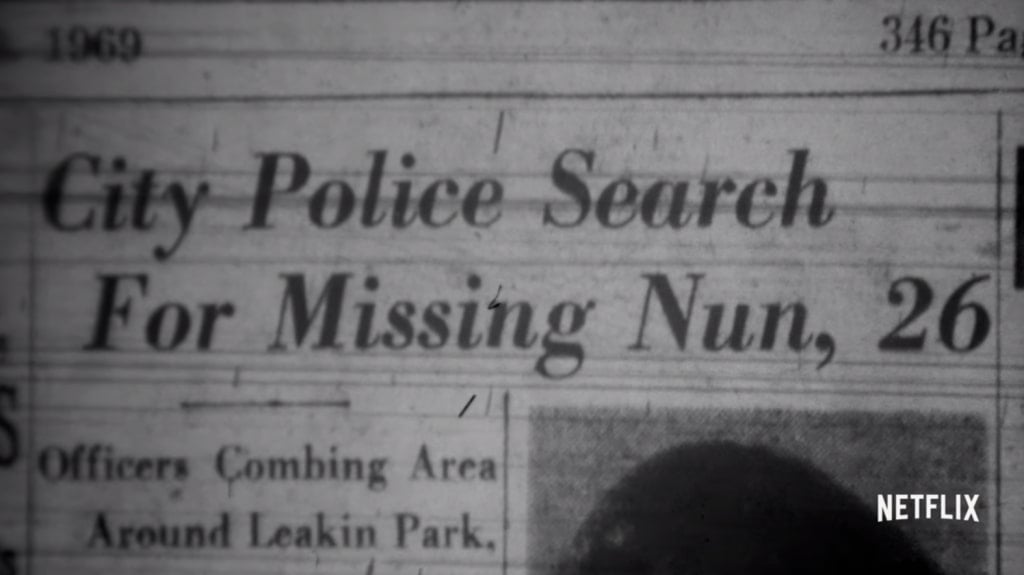

The story starts with a disappearance, and ends with a murder. Or does it? There was also a scandal, and abuse, and many secrets — some of which have since come to light, but some of which have remained shrouded in darkness. The murder is part of it, of course, but after all these years, the case still lacks a satisfactory conclusion. Among the many questions that have been left unanswered is this: Who killed Sister Cathy?

If you’re a regular reader of The Ghost In My Machine, I’d be willing to bet that you’ve already heard of the upcoming Netflix docuseries The Keepers. As indicated by the success of 2015’s Making A Murderer, an examination of the Steven Avery case which was 10 years in the making, as well as HBO’s The Jinx, also released in 2015 and which led to the arrest of Robert Durst, and the first season of the podcast Serial, about the murder of Hae Min Lee and released in 2014, public interest in true crime is at a high; as such, it’s to be expected that documentaries like The Keepers would continue the trend. Directed by Ryan White, this one will examine the 1969 disappearance and murder of Sister Catherine “Cathy” Cesnik, a nun who taught English and Drama at Baltimore’s Archbishop Keough High School — a disappearance and murder which have gone unsolved nearly 50 years later.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

Since The Keepers is due to hit Netflix in just a few days — May 19, to be precise — now seems like a good time to revisit what we know.

Born in 1942, Cesnik grew up in the Lawrenceville area of Pittsburgh, Pa. She attended parochial school as a child before going on to St. Augustine Catholic High School in 1956; Cesnik was deeply religious, and from an early age had already begun planning for a life dedicated to God. After high school, she entered the School Sisters of Notre Dame as a member of the Baltimore Province covenant, taking her final vows on July 21, 1967. She had already begun teaching two years prior, however; at the time, Archbishop Keough High School (later known as Seton Keough High School) had just opened, and Cesnik had quickly become known as a caring and inspirational teacher — “the kind of teacher you never forget,” as one former student described her years later to the Baltimore Sun/City Paper.

In June of 1969, however, Cesnik asked for and was granted permission by the School Sisters of Notre Dame to enter a period of “exclaustration,” in which she would live outside the convent for a period of time. During this time, she would eschew the nun’s habit and dress as a civilian; she would, however, “remain bound by [her] vows,” according to religious website Catholic Culture’s definition of exclaustration.” She also determined that she would spend the 1969 – 1970 school year as a “missionary” teacher at Western High School, a local public school. She moved into a two-bedroom apartment with Sister Helen Russell Phillips, also a nun who taught at Western High.

On the evening of Nov. 7, 1969, Cesnik went out to run some errands, alerting Phillips to the fact at about 7:30pm — she said she needed to stop at the bank, as well as buy a gift for a cousin who had recently gotten engaged. We know that she cashed a paycheck at a bank in Catonsville, Md., about 10 miles west of Baltimore; we also know that she bought some buns at a bakery at the Edmondson Village Shopping Center, which lies midway between Baltimore and Catonsville.

And that’s the last we know of her whereabouts before her remains were found two months later.

At 11pm the night of Nov. 7, Phillips, worried that Cesnik hadn’t come home yet, called two priests who were friends of hers. They arrived at the apartment the two women shared, then called the police. Cesnik’s car was located later that night nearby, unlocked and parked illegally — a fact which was doubly strange and even downright disturbing, given that Cesnik had a reserved parking space at the apartment building in which she and Phillips lived. There was no reason for her to park elsewhere, nor for her to leave her car unlocked.

The investigation went nowhere.

On Jan. 3, 1970, Cesnik’s body was discovered by two hunters at a garbage dump outside of Baltimore. She had suffered a great deal of trauma; although an autopsy determined that the cause of death was due to being hit in the back of the head with a blunt object, her neck also bore choke marks. It was a violent death, and likely not a quick one. She was 26 years old at the time of her disappearance — and 50 years later, we still don’t know exactly what happened.

We have an idea, though. We know what might be connected. And a group of former students, all now in their 60s and 70s, are determined to get justice for Sister Cathy.

In 1994, a woman came forward with accusations — big ones. She had been a student at Archbishop Keough High School at the time of Cesnik’s murder, and what she came forward with was enough to reopen the investigation: She claimed not only that Father Joseph Maskell, who had been the chaplain of Archbishop Keough at the time of Cesnik’s death, had sexually abused her, but also that he had, one day after school about a week after Cesnik had gone missing, given her a ride — but not home. Instead, she claimed he had driven her to a garbage dump. He had allegedly shown her a body of a woman wearing an aqua-colored coat and with her face crawling with maggots — a body she said recognized as Cesnik’s. She said he told her, “You see what happens when you say bad things about people?”

The girl, terrified, remained silent for 25 years. But when she finally stepped forward as an adult, she presented details to the police that hadn’t been made public at the time — the maggots. According to Cesnik’s autopsy, maggots had been found in her throat.

The case was subsequently reopened.

The woman, who remained anonymous as only “Jane Doe” in court documents 1994 but later came forward to identify herself as Jean Hargadon Wehner, isn’t the only former student to have reported being allegedly abused by Maskell, as well as Archbishop Keough’s director of religious services, Father Neil Magnus. The ensuing lawsuit sought damages for Wehner and another former student, later identified as Teresa Lancaster; the case included testimony about the alleged abuse from a whopping 30 people who said they knew about it. The church does now acknowledge that the accusations are credible, according to a spokesperson for the Archdiocese of Baltimore, reports the Huffington Post. And it’s likely that both Maskell’s and the church’s deep connections protected him from the allegations at the time, hence why the original investigation yielded so little.

The working theory is that Cesnik knew about the abuse, and tried to stop it. In interviews with HuffPo, Wehner and several former students recounted ways in which Cesnik tried to protect them — making excuses for them when they were called to Maskell’s office which would prevent them from having to go, for example — and otherwise looked out for them. Most terrifying, though, is this: One former student, who remains anonymous, told HuffPo that the night before Cesnik vanished, she went to speak to her at her apartment — only for Maskell and Magnus to charge into the place. The woman told HuffPo, “Maskell glared at me. He knew why I was there,” after which she left. The next day, she said, Maskell threatened her with a gun in his office, telling her that he would kill not only her, but also her family and her boyfriend if she ever spoke to anyone of the abuse.

And then, Censnik was gone.

Charges were never brought, though, and a ruling was never made. When the investigation was reopened in 1994, Maskell fled first to a residential treatment facility and later to Ireland; he died in 2001. Magnus, meanwhile, had died in 1988. If Cesnik’s death was in fact connected to the allegations, true closure may never be had with its key players gone.

Archbishop Keough High School itself is gone now, too. It merged with Seton High School to become Seton Keough High School in 1988, but in 2016, it was identified for closure by a master planning study of Baltimore Catholic schools. It will close its doors for the last time after the end of the 2016 – 2017 school year.

The women who suffered the alleged abuse, however, have found support in each other, according to the Huffington Post — and that, as they say, isn’t nothing.

I don’t know how successful The Keepers will be. I’ve been able to dig up virtually nothing about its filming process, so I don’t know whether it, like Making A Murderer, occurred organically and then found a home on Netflix later on, or whether it was put into production specifically to capitalize on the revived interest in true crime we’ve seen in recent years. I’m hoping it’s the former; you can always tell when something is made because the story itself demands it be told, and the work is almost always better for it. We’ll have to stay tuned to find out, though.

Even if the mystery itself is never truly solved.

Recommended reading:

With New Lead, Police Reopen Old Murder Case.

Buried in Baltimore: The Mysterious Case of a Nun Who Knew Too Much.

Find A Grave: Catherine Ann “Cathy” Cesnik.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photos via Jim, the Photographer, Jlancto/Flickr; Wikimedia Commons]