Previously: The Miniature Coffins of Arthur’s Seat.

As of 2010, the town of Keddie in Plumas County, Northern California has a population of 66. Just 66 people. That’s why it’s not technically even a town; it’s a census-designated place. Exactly half of those 66 people were male and half of them were female; only seven were under the age of eighteen, with the other 59 being legal adults. Most of these adults — 39 of them — are over the age of 50.

Although Keddie is undoubtedly beautiful, it’s not the kind of place you want to raise your kids — or at least, it isn’t anymore. A former railroad town that once harnessed the beauty of its location in the foothills of the Sierra Nevadas by playing host to lodges and campgrounds, it’s known these days for one reason, and one reason alone: The brutal 1981 murders that occurred in Cabin 28 of the Keddie Resort. It’s been almost 34 years since the Keddie Murders rocked the town in 1981, and we are still no closer to knowing who perpetrated them — or why. And like so many cold cases, we likely never will. All we have left are the decaying remains of a former mountain paradise, a handful of spooky stories, and a tragic, unsolved mystery.

In the spring of 1981, 36-year-old Glenna Sharp, who was known primarily by her middle name, Sue, had been renting Cabin 28 at the Keddie Resort for about six months. Although Keddie had once been a thriving railroad town with a scenic hotel and lodge for travelers, it had fallen far from its glory days at the turn of the century; by the 1980s, many of the cabins at the Keddie Resort were rented not to holiday-makers, but to low-income families. Sharp and her five children — John, age 15; Sheila, 14; Tina, 12; Ricky, 10; and Greg, just five — were one of those families, having taken up residence in the cabin in November of 1980.

The night of April 11, 1981, began — as these things often do — as a night like any other. It was a Saturday, so none of the Sharp children had school the next day; as such, it wasn’t unusual that Sue Sharp had assented to allow a friend, a 12-year-old neighborhood boy named Justin, spend the night with Ricky and Greg. Sharp herself and her daughter Tina also remained at home in Cabin 28 with the three boys. Her other daughter, Sheila, had gone the cabin next door for the night; one of her friends lived in Cabin 27. Meanwhile, John had spent the day six miles away in Quincy, CA with his friend Dana Wingate, a 17-year-old with a reputation for trouble. They had planned to return home that night, joining Sharp, Tina, Ricky, Greg, and Justin in Cabin 28.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

We still don’t know exactly what happened that night. But what we do know is this: The morning of April 12, Sheila Sharp arrived home at approximately 7:45 in the morning to find the bodies of her mother, her brother John, and Dana Wingate lying in the living room of Cabin 28. They had been bound with medical tape and electrical wire. Sue Sharp had been covered with a yellow blanket; the two boys remained uncovered and lying nearby. Sharp and John had both been struck with a claw hammer, as well stabbed repeatedly with a steak knife found at the scene. Wingate, who along with John was still wearing his coat, had been strangled as well as bludgeoned and stabbed. The knife had had such force applied to it that it had bent almost double. Tina was nowhere to be found.

Sheila ran from the cabin, screaming for neighbors to call law enforcement. When they arrived, they found very little in the way of evidence: A bloody fingerprint on a wooden post in the backyard, blood on the sheets of Tina’s bed, blood on the doorknob of the bedroom in which Ricky, Greg, and Justin had been sleeping. Miraculously, the three boys were found completely unharmed; while Sheila waited for the sheriff to arrive, she helped them climb out of the house through the bedroom window.

The scanty evidence failed to shed much light on the crime, although it’s possible that part of the issue may be the botched nature of the scene: It remained unsecured by the sheriff’s office, nor was the Department of Justice notified. In any event, it’s believed that, due to the brutal nature of the murders, they were committed by someone known to the family — that it was personal. The fact that the boys were still wearing their coats may suggest that they arrived home either shortly before the crime began — or possibly while it was underway. Most curious of all, though, was the blood on the doorknob.

In the hopes that Greg, Ricky, and Justin — the sole survivors of the attack — might have seen or heard something to set the investigation on the right track; unfortunately, though, they were unable to recall anything of use, even under hypnosis. Ricky and Greg said they had been asleep the whole time — and Justin? Justin remains a mystery. His story varied dramatically with each telling: He claimed to have seen who committed the murders; then he claimed that he only dreamed he saw the crime happen; he claimed he dreamed covering Sue Sharp with a blanket and attempting to stop her bleeding; and finally he claimed to have seen absolutely nothing. His testimony did not hold up under a polygraph test — although the investigators kept coming back to the blood on the doorknob. Its presence, combined with the boy’s inconsistent stories and the fact that the bedroom door was partially open, led law enforcement to believe Justin had touched at least one of the bodies; however, it has never been definitively proven that he did so.

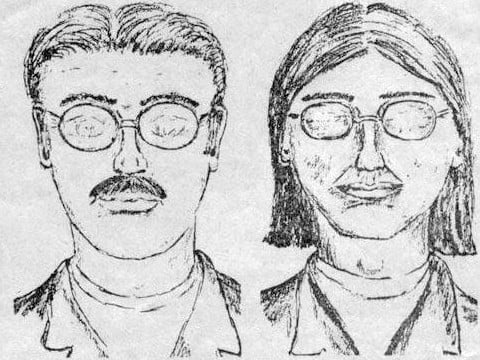

Who may have done it? The investigation was never able to figure it out. Boyfriends of Sue Sharp were questioned and released — but perhaps of most interest were Marty Smartt and Severin John “Bo” Boubede. Smart and his wife, Marilyn, lived in Cabin 26 at the Keddie Resort; Boubede had been staying with them after Smart had first met him at a VA hospital a few weeks earlier.

Marilyn was a mother of two — one of whom was Justin.

Smart, Marilyn, and Boubede had apparently stopped by Cabin 28 on their way to a bar on the evening of April 11; Marilyn said she had asked Sue Sharp to come with them, but that Sue had turned them down. At the bar that night, Smart, whom Marilyn later noted was abusive both emotionally and physically, had angry words with the manager over the music playing, after which the three of them left. Marilyn went to bed; Smart, however, phoned the bar to complain again before returning to it with Boubede.

Although the Plumas County Sheriff’s Office failed to notify the Department of Justice of the crime right when it was first discovered, they did eventually bring the DOJ in. Once Smart and Boubede were identified as persons of interest, they questioned the two of them as well as Marilyn. It was determined that they were uninvolved with the murders—but how or why remains unclear. The interviews conducted by the DOJ appear to be somewhat lacking, and upon further examination, it became clear that much of what Boubede told them about himself — that he was a former police officer, that he had been living in Keddie for a month, that Marilyn was his niece and so on — was untrue. Boubede had never been an office of the law; he had been in Keddie for only 12 days; and he and Marilyn Smart were not related in any way.

For reasons no one has been able to successfully explain, Smart and Boubede were released.

Some years after Smart’s death in 2000, his therapist apparently stepped forward and said that Smart had confessed to the murder of Sue Sharp. Many believe Smart to have, in fact, been responsible for the crimes; among other things, it explains why Justin and the two younger Sharp boys had been left unharmed (it would have looked suspicious if only Justin — his wife’s son — had been left alive). But with the case so many years out, and with Smart himself dead, there is no way to discern whether or not he actually committed the murders.

But what of Tina? Tina, who was missing from the cabin the morning of April 12? Her fate was not discovered until three years later, although she fared no better than her mother and the two boys. In 1984, a portion of a human skull surfaced in Camp Eighteen, an unincorporated Butte County community located about 29 miles directly away from Keddie (although the only driving route between the areas is somewhat roundabout, covering 57 miles). Several months after the discovery, the Butte County Sheriff’s Office received an anonymous call claiming that the skull fragment belonged to Tina Sharp. A subsequent search of the area unearthed other bones and fragments, include a jawbone; however, beyond the fact that she had been abducted from the cabin and later murdered, no further clues were able to be discerned from the finds.

Perhaps most heart-wrenching about Tina’s story, though, is this: Upon arriving at the scene of the crime in 1981, the sheriff’s office did not notice that Tina was missing. Justin allegedly attempted to tell them she had been taken from her bed, but he seems to have been ignored. Given that the first 48 hours in the case of an abduction are the most crucial, there’s no telling what might have happened had her disappearance been noted from the get-go. If a search for the missing girl had been organized, perhaps she may have escaped her tragic end.

These days, Plumas County Sheriff’s Office will not discuss the case with anyone. They will not explore it further, and they will not work with other law enforcement agencies to get to the bottom of it. Over the years, evidence has been lost or destroyed, leaving almost nothing left from which to work.

Cabin 28 was demolished in 2006. In the decades following the murders, the resort further decayed; owner Gary Mollath attempted to sell it in 1984, but there were — perhaps unsurprisingly — no takers. In 2001, the cabin itself still existed; its doors were nailed shut and its windows were covered with plywood, but it stood on the same spot it always had. Stories clung to it, of course, because what else could the cabin become but a haunted house? Ashley Conte, Mollath’s stepdaughter, told SFGate that she occasionally saw “murky forms and rocking chairs” in the house; she also once found a pitchfork and the word ‘no’ carved into the kitchen door. “When we went back a half-hour later,” she said, “the words and the pitchfork were gone.” Others have reported hearing moans, slamming doors, and footsteps at times when the cabin was clearly unoccupied.

But perhaps this is how we deal with places plagued by bad memories: We create stories about them. We make what was a very real tragedy into something of a campfire tale, a spooky story to tell at night. Stories, after all, can’t hurt us — not in the same way whoever attacked the Sharp family did. As history falls into legend, we begin to feel safer again, even if that safety is nothing more than a false sense of security. There is evil in the world — but we don’t have to look to the paranormal to find it.

Sometimes we only have to look as far as the people next door.

Recommended reading:

Exorcising the Ghosts of the Past.

Cold Case: The Keddie Murders.

The Strangers versus Keddie Cabin Murders.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!