Previously: The Town That Killed Ken McElroy.

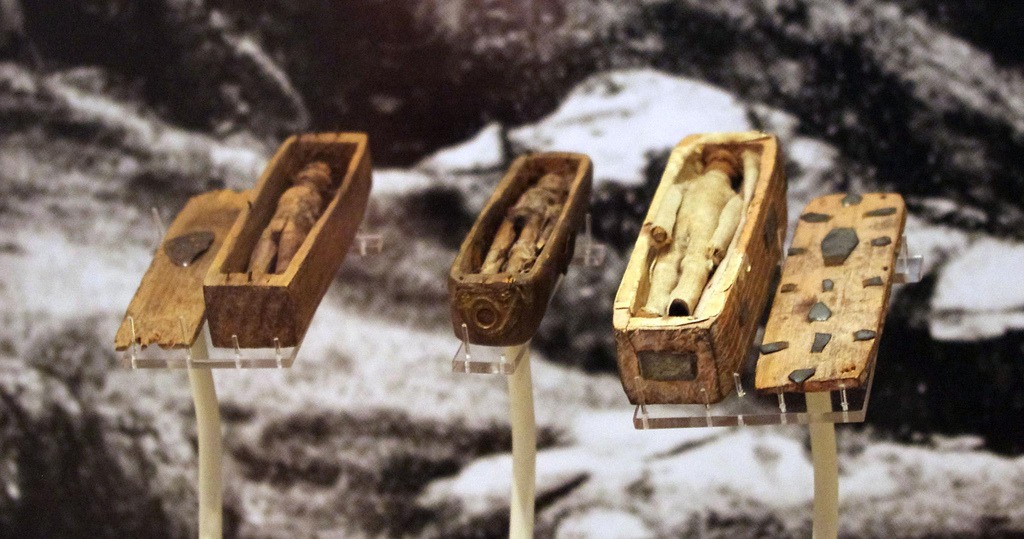

On the fourth level of Edinburgh’s National Museum of Scotland is a curious exhibit: A collection of tiny coffins, each measuring just 95mm in length and containing a wooden figure of a man. We don’t know what the miniature coffins of Arthur’s Seat are, or why they were found where they were, or who might have put them there; and what’s more, we probably never will know. But they remain one of the most peculiar archeological discoveries of the 19th century, a mystery that continues to bug us to this very day.

They were first discovered in June of 1836 by five boys. They had gone out hunting for rabbits on the northeast slope of the hill known as Arthur’s Seat (which itself may or may not have gotten its name from Arthurian legend); according to writer and researcher Charles Fort, they stumbled upon some thin sheets of slate in the side of a cliff, which they then pulled out. Here’s how Fort described what they found next (via Smithsonian):

“Little cave.

Seventeen tiny coffins.

Three or four inches long.

In the coffins were miniature wooden figures. They were dressed differently in both style and material. There were two tiers of eight coffins each, and a third one begun, with one coffin.

The extraordinary datum, which has especially made mystery here:

That the coffins had been deposited singly, in the little cave, and at intervals of many years. In the first tier, the coffins were quite decayed, and the wrappings had moldered away. In the second tier, the effects of age had not advanced so far. And the top coffin was quite recent looking.”

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

Weird, right? Although there were 17 to start, less than half of them have survived the intervening centuries. The boys who found them wreaked a certain amount of havoc on them right after unearthing them — wrote The Scotsman in July of 1836, “a number were destroyed by the boys pelting them at each other as unmeaning and contemptible trifles” — with the rest ultimately finding their way to a jeweler by the name of Robert Frazier. Frazier auctioned them off after his retirement in 1845 for four pounds (approximately £357 today); then they stayed out of sight until 1901, at which point eight of the coffins were donated by one Christina Couper to the National Museum of Scotland. Or at least, we’re pretty sure they’re the ones Frazier auctioned off — we’re not totally sure. But a few newspaper accounts seem to corroborate the idea that they were once Frazier’s, so that’s the story we generally believe to be true. It’s worth noting that there are a few other stories floating around about the coffins’ discovery; however, their veracity is often suspect, so take them with a grain of salt.

Which brings us to the biggest mystery of all: What were the coffins for? The theories are many, but we’ll probably never know which, if any, of them is correct. At one point, they were suspected of having ties to witchcraft; it was thought that they represented people upon whom spells had been cast, not unlike voodoo dolls. These days, though, we tend to run less frequently to cries of “WITCHCRAFT!” about things we don’t understand, so this particular theory has fallen somewhat out of fashion. More recently it’s been posited that the figures have something to do with the Burke and Hare murders of 1828.

For those of you not familiar with the history, here’s the short version: William Burke and William Hare, two Irish immigrants living in Edinburgh, struck upon the idea not of robbing graves in order to sell the cadavers to the Edinburgh Medical School as anatomical subjects — a not uncommon activity of the time — but rather, of actually killing people in order to create fresh cadavers they could sell. They were caught eventually; Burke was tried and hanged, while Hare was released and vanished from the record. Before the law finally caught up with them, though, they had sold 17 bodies to a surgeon, Dr. Robert Knox — 16 of whom they had killed themselves.

You can see where this is going, right?

As the website the Museum of Ridiculously Interesting Things notes, one of the more intriguing details of the set is that some of the figures within the coffins have arms, while others don’t. It looks like the ones sans arms had the appendages removed before they were placed in their coffins—which suggests that they might not have been intended for burial. Researchers from the Universities of Edinburgh and Virginia concluded in a 1994 study that the figures’ design may have been based on a set of wooden soldiers originally manufactured in the late 16th century; they may not have been buried until the 1830s, not too long before the five boys found them in 1836.

So, taking this detail in conjunction with the facts of the Burke and Hare case, some have theorized that the 17 coffins represent Burke and Hare’s victims. The time frame is right — if the murders happened in 1828 and the coffins were buried sometime in the early 1830s, Edinburgh still would have been reeling from the murders around the time of the burial. It was believed at the time that the souls belonging to bodies that had been dissected would not rise to life at the final judgment; perhaps the coffins could have been an attempt to grant the victims the peace in the afterlife robbed from them by Burke and Hare.

But again, we’ll never know. Mysteries like this one hit me particularly hard, because no matter how educated our guesses are, they’re still just that: Guesses. I would even argue that our guesses in this case aren’t that educated in the first place — we’re kind of grasping at straws which may or may not simply be coincidental in nature. But at least we still have the coffins and their tiny wooden occupants; you can visit them daily at the National Museum of Scotland, along with other such treasures as the Lewis chessmen and the Queen Mary harp. Got a theory of your own? Do tell; in cases like this, I’m a firm believer in the old adage, “the more, the merrier.”

Recommended reading:

Edinburgh’s Mysterious Miniature Coffins.

The Mysterious Coffins of Arthur’s Seat.

Lost Edinburgh: The Arthur’s Seat Coffins.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!