Previously: The Collyer Brothers.

It’s not uncommon for bottles, jugs, and other vessels to be among the artifacts unearthed at sites long associated with human history — but some of those vessels are more than just plain old bottles. Some of them, it turns out, are witch bottles. What are witch bottles, you ask? Well, per the Wikipedia page on witch bottles — which, yes, is a delightfully creepy thing that exists — they were “countermagical devices used as protection against other witchcraft and conjure” used during eras when the fear of witches and witchcraft was at its height.

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available for purchase now!]

They worked like this:

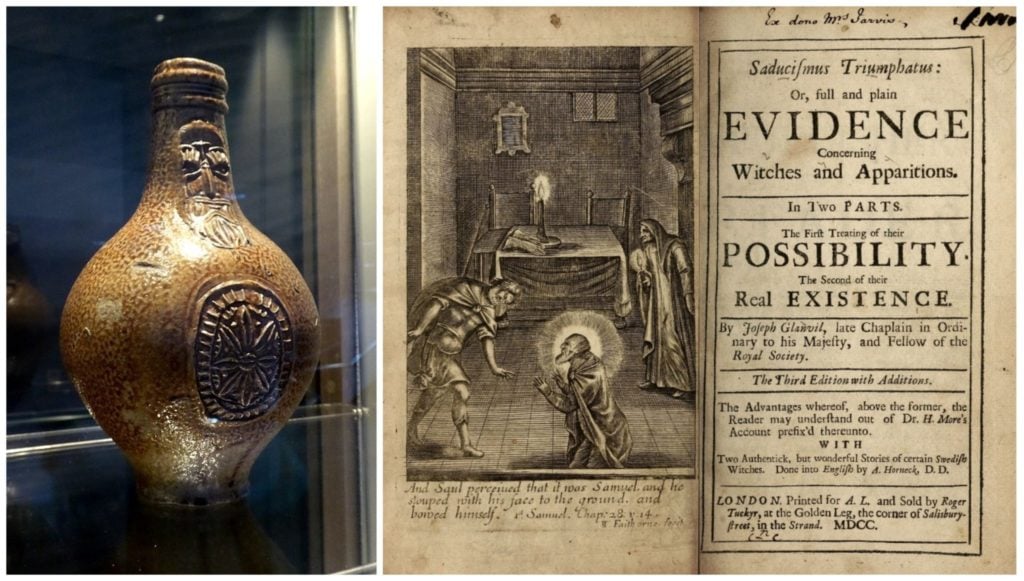

If you suspected that you had been bewitched or that you were suffer the ill effects from a spell put upon you by someone who practiced witchcraft — or if you simply wanted to put a bit of a preventative ward on your home — you were to take a bottle and fill it with some… peculiar ingredients. Bent pins and human urine were among the most commonly used ingredients, but nail clippings, iron nails, hair, thorns, and other sharp bits and pieces were believed to work, as well. The bottle itself, meanwhile, could be glass or ceramic; early witch bottles might even be “Bellarmine” bottles adorned with human faces.

Then, once the bottle had been prepared and sealed, you were to bury it beneath either the threshold or the hearth of your home. If a witch tried to enter your home by either entryway (and yes, witches were commonly believed to enter homes through chimneys), the urine would attract them and draw them — or perhaps their non-corporeal selves; it’s not entirely clear — into the bottle; then, once they were inside, they would be impaled on the sharp objects, thus trapping them inside the bottle. The hearth was a particularly good location or the witch bottle, as the heat from the fire could also activate the ingredients and make things rather uncomfortable for the witch.

Witch bottles date back to different eras depending on where you find them. In Europe — namely in England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales — witch bottles were in use during the medieval and early modern eras; prosecution for the crime of witchcraft peaked in Europe between 1580 and 1630, so many of the bottles that have been located overseas can be traced to those years, give or take a few decades. In the United States in North America, however, witch bottles were in use a bit later (partially due to the fact that European colonists didn’t arrive and start forcibly taking over land here and imposing their own customs and culture until the 17th century): All of the witch bottles that have been found in the U.S. are from the mid-18th century or later. (For reference, that’s about half a century after the Salem witch trials, which occurred between 1692 and 1693.)

However, it’s worth noting that we have many fewer witch bottles in the United States than we do in Europe; some 200 have been found overseas, while in the U.S., fewer than a dozen have been located. As such, it’s possible that witch bottles may have been in use earlier than the mid-18th century — we just haven’t found them yet. In theory, colonists could have brought over the practice as early as 1585, when the first Roanoke colony was established.

There’s still a lot we don’t know about witch bottles — but we do still have a surprising amount of information about this strangely specific little charm, thanks to some enterprising researchers and academics. For more, check out the below resources:

Further Reading:

“Is There A Witch Bottle In Your House?” by Allison C. Meier for JSTOR Daily. This terrific article appeared in the academic resource JSTOR’s free-to-access online publication JSTOR Daily in 2019. Researched and written by Allison C. Meier, a writer who focuses on history, architecture, and visual culture who has previously been on the staff of publications like Hyperallergic and Atlas Obscura (both sites I adore), it serves as a solid introduction to the subject, discussing what witch bottles were, how they were made, and what may have contributed to their popularity during the era in which they were in use. The most interesting takeaway from it for me is this excellent point:

“…The rather unpleasant ingredients in witch bottles reflected real threats to seventeenth-century people even as they were concocted for supernatural purposes. It’s probable many were made as a remedy at a time when available medicine fell short. ‘Urinary problems were common both in England and America during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and it is reasonable to suppose that their symptoms often were attributed to the work of local witches,’ scholar M.J. Becker notes in Archaeology. ‘The victims of bladder stones or other urinary ailments would have used a witch bottle to transfer the pains of the illness from themselves back to the witch.’ In turn, if a person in the community then had a similar malady, or physical evidence of scratching, they might be accused of being the afflicting witch.”

JSTOR Daily is great, by the way; it seeks to “[contextualize] current events with scholarship” by “drawing on the richness of JSTOR’s digital library of more than 2,000 academic journals, thousands of monographs, and other materials.” What’s more, all of the stories published on JSTOR Daily include links to research on JSTOR itself that’s both free and publicly accessible. If you’re into history — weird or otherwise — and often find yourself reflecting on the role the past plays in our present, JSTOR Daily is worth adding to regular reading rotation.

Saucismus Triumphatus by Joseph Glanville.Bearing the full title of Saducismus triumphatus, or, Full and plain evidence concerning witches and apparitions in two parts : the first treating of their possibility, the second of their real existence, this treatise on witchcraft expanded upon an earlier, shorter work by Glanville titled A Blow At Modern Sadducism; however, while A Blow At Modern Sadducism was originally published in 1668, during Glanville’s lifetime, Sacismus Triumphatus was published posthumously in 1681 (Glanville died in 1680).

Both works attempt to prove the existence of witchcraft and include among their contents a wide variety of gathered bits of witch-related folklore — Saucismus Triumphatus bears the distinction of containing the earliest known description of a witch bottle. In it, an ailing woman’s husband is instructed by an old man to “take a Bottle, and put his Wives Urine into it, together with Pins and Needles and Nails, and cork them up, and set the Bottle to the fire, but be sure the Cork be fast in it” in order to stave off what was believed to be a bewitchment. When this strategy failed to yield results, the old man further instructed the husband to “take your Wive’s Urine as before, and Cork it in a Bottle with Nails, Pins and Needles, and bury it in the Earth.” This time, it worked — although it apparently killed the “Wizzard” who had allegedly bewitched the woman in the first place.

This description can be found in the Advertisement in the Relation VIII of the section titled “Proof of Apparitions Spirits, and Witches, from a choice Collection of modern Relations.” In the scan hosted at the Internet Archive of the book’s third edition, which was printed in 1700, the description is on page 104; meanwhile, in the plain text version from 1681 hosted over at the University of Michigan library’s website, it’s on page 206.

“The Witch Bottle Of Bow Lane” lecture by Gillian Kenny. On April 12, 2017, medieval and early modern European historian Dr. Gillian Kenny of Trinity College Dublin gave a lecture at the Little Museum of Dublin on magic and its uses in medieval Ireland — and the center of the lecture was a witch bottle found at Bow Lane, just off Mercer Street in Dublin, in 2012. The bottle, which dates to 1600, is notable for being not just a plain glass bottle or clay vessel, but specifically a bottle featuring a Bellarmine face — the face of man, so named for the Italian cardinal Roberto Bellarmine. It was also found intact and sealed, which is pretty remarkable.

Kenny’s specialty isn’t limited to witchcraft; she focuses on women’s roles in medieval and early modern European society. As she puts it, she is “more particularly… interested in how women’s lives were conducted in Ireland, Scotland, and Wales from the period c. 1066 – 1560” — that is, from the Norman Conquest up through the beginning of the Renaissance. However, she also researchers “the lives out Outsiders in medieval society” — so, given that witchcraft is both typically coded as female and the provenance of outsiders, it makes a lot of sense that her work has routinely covered witches and witchcraft in Irish, Scottish, and Welsh history.

Her hour-long lecture uses the witch bottle of Bow Lane as a springboard to discuss magic and witchcraft in Ireland throughout history more broadly. The full lecture is absolutely worth watching; if you can’t spare an hour, though, you can watch the greatest hits of it in a five-and-a-half-minute-long video here instead.

You can read more of Dr. Kenny’s work at Academia.edu; also check out her book Anglo-Irish and Gaelic Women in Ireland, c.1170–1540, published by Four Courts Press in 2007. Margaret Murphy reviews it for Eolas: The Journal of the American Society of Irish Medieval Studies here.

Witchcraft And Magic In Ireland by Andrew Sneddon. Recommended by Gillian Kenny in her lecture. Currently of Ulster University, Dr. Sneddon is a “social and cultural historian, with a special interest in Britain and Ireland, viewed in an international context”; he published Witchcraft And Magic In Ireland in 2015. The book is, somewhat remarkable, “the first academic overview of witchcraft and popular magic in Ireland,” with its focus spanning medieval through early modern European history.

On witch bottles, Sneddon notes that they were a variety of “sympathetic magic” which cunning-folk might “[use] remotely to coerce [a] witch” into lifting a spell they had placed on someone else. The idea behind the burying or heating of the bottles is that, as they were “symbolic of the witch’s bladder, the sharp objects and/or the heat would cause searing pain, forcing the suspect to reveal themselves in order to seek relief.” (Remember the note about urinary issues common to the era in the JSTOR Daily piece? Makes sense, no?)

“An American Witch Bottle” by M.J. Becker for Archaeology. One of the articles cited in the JSTOR Daily piece, this one is quite old — it was originally published in 1980 — but it’s of much significance: Its writer is the one credited with finding the very first witch bottle located in the United States. In the article, Becker describes the bottle, which was unearthed in 1978, as follows:

“A curious bottle unearthed during recent excavations in Governor Printz State Park in Essington, Pennsylvania, provides a glimpse of early American witchcraft—unique evidence of a special ‘white witchcraft’ hitherto known only from England. This squat piece of glasswork with a bright gold patino over its dark olive color had been buried upside down in a small hole. Two objects were deposited under the shoulder of the bottle: A piece of a long, thin bone from some medium-sized bird, possibly a partridge, and a redware rim sherd from a small black-glazed bowl. The bottle contained six round-headed pins and had been stoppered tightly with a whittled wooden plug.”

Noted Becker, “What makes this bottle and its contents curious are their uniqueness; no other bottle with similar contents has ever been found in the United States.”

That was true at the time; since then, though, other bottles have been discovered. Still, though, it was a watershed moment, particularly given that American witch bottles remain so much rarer than British ones.

“Buried Bottles: Witchcraft And Sympathetic Magic” by M. Chris Manning. This one-page overview of witch bottles is surprising in depth; however, its most useful element is the center panel, which lists and describes the eight witch bottles that were found in the United States prior to 2016.

As Manning points out, witch bottles in the United States differ from those found in England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales in a few ways: For one thing, they’re dated later — the mid-18th century, as opposed to the 16th and 17th centuries — and for another, they’re all glass bottles, as opposed to stoneware jugs.

The vast majority of the American bottles come from New England and the Mid-Atlantic regions: Two were found in Pennsylvania (including the Essington bottle found by M.J. Becker); two in Maryland; and one each in Delaware, Virginia, Rhode Island, and, interestingly, Kentucky. (The Kentucky bottle is obviously the odd one out, in that Kentucky is part of the Southeastern United States, rather than New England or the Mid-Atlantic area.) If you want to find out more about each of these bottles, Manning’s piece gives you all the identifying info you need to get started digging a little deeper.

But those eight bottles aren’t the only ones that have been found anymore! There’s also…

“A Civil War-Era ‘Witch Bottle’ May Have Been Found On A Virginia Highway, Archaeologists Say” by Peter Jamison for the Washington Post. The news of this bottle’s discovery — or, more accurately, the announcement that archaeologies finally have a better idea of what it actually was — is what prompted me to put witch bottles on the Creepy Wikipedia to-do list in the first place.

Back in 2016, a bottle that archaeologists dated back to the Civil War was dug up along a highway in Virginia — Interstate 64, to be precise, near Yorktown (yes, that Yorktown, albeit during a different war). But the bottle wasn’t empty; it was filled with nails. Its contents combined with its location are what led researchers originally to believe that it had simply been what it seemed to: An empty bottle re-purposed to store nails used in the construction of the fort formerly located in the area. But in early 2020, archaeologists from the College of William & Mary, who had found and were studying the bottle, announced that they now thought it was something else: A witch bottle.

Knowing that witch bottles tended to come into use during times of strife, Joe Jones, director of the William & Mary Center for Archaeological Research, made an astute observation about the bottle. If it is, in fact, a witch bottle — and right now, it seems likely that it is, then “it’s a good example of how a singular artifact can speak volumes,” said Jones in a press release. “It’s really a time capsule representing the experience of Civil War troops, a window directly back into what these guys were going through occupying this fortification at this period in time.”

How To Make A Witch Bottle. Interested in trying to make the modern-day equivalent of a witch bottle? Good news: There are plenty of tutorials from those who practice Wicca or other modern forms of witchcraft available right on the internet.

This one from the blog of Sabbat Box, a pagan subscription box service, is probably the most helpful; it details what adjustments to make depending on what you want your witch bottle to accomplish, offers suggestions for materials, and so on and so forth. (You don’t have to use urine if you don’t want to.)

This one from the Witch’s Library is similarly detailed, and includes a few suggestions for possible combinations of ingredients for achieve specific goals.

And this one is probably the most entertainingly written guide I’ve found (the writer is correct! Witch bottles are literally full of piss and vinegar!), so if you like your witchcraft with a dose of humor, that one’s a good one to go by.

There are plenty of other guides, sets of instructions, and tutorials out there, though, so hey, keep digging if none of these appeal to you. There’s likely something out there that’s more along the lines of what you’re looking for.

Category: Objects Believed To Protect From Evil on Wikipedia. I was delighted to discover that Wikipedia actually has a category for “Objects believed to protect from evil” on it. There aren’t a ton of pages cataloged on it, but there are enough — 22, including witch bottles — to keep you occupied for a while. Some of the included objects are also delightfully surprising: For example, I actually didn’t know that nutcrackers are more than just holiday decorations/items used to, uh, crack nuts; they’re apparently also meant to serve as a household guardian or protector in German folklore. I was also quite taken by the entries on concealed shoes, hoko dolls, and Sheela na gigs.

Witch Bottle on Spotify and Bandcamp. Seattle-based band Witch Bottle didn’t come up with their name willy-nilly; indeed, it’s quite fitting, given that they call their genre of music “witch folk.” Featuring Alexandra Zefkeles on accordion, Bree Sadira Rose on the musical saw, Jesse Stout on drums, and all three on vocals, the band’s sound is dark and folk-y, but also somewhat industrial. Their own description of themselves tells you just about everything you need to know about them. Per their Facebook page:

“Witch Bottle emotes energies of folklore, fantasy, and feral spirits through the tales we sing. Our songs are inspired by our magical community, ancient folklore, and the most fanciful corners of our imaginations.

With a playful balance of light and dark, we will transport you through worlds with us until you find yourself in a little bell jar on our mantle upon emerging from your wormwood dreams.”

But in case you want to know a little more, they seem to have formed sometime around 2015 (that’s when their Facebook page was created) — although according to Bree Sadira Rose, they didn’t initially intend to actually become a band in the first place. According to an interview with Seattle Pi she gave in 2016, she and accordionist Alexandra Zefkeles had both fallen in love with the sound of the musical saw, which Rose could play, and “decided that [these two] instruments would have some lovely stories to tell if they joined together to converse.” They started with covers and simple songs and mostly busked or played for house parties — but as they grew, and as new members joined, their sound evolved, they started performing their own tunes, and, well… here we are.

Their two albums, Forest Spell (2019) and Femme Feral (2018), are available on both Spotify and Bandcamp; they’ve also got a few additional tunes, including some demos, at their Bandcamp page.

“Antiques Roadshow Expert Drank Urine Thinking It Was Port” by Craig Simpson for the Telegraph. And lastly, a horrifyingly hilarious tale to close out the day on: In 2016, glass specialist Andy McConnell was valuing a 150-year-old bottle found under the threshold of a home in Cornwall. The sealed bottle contained a liquid — so as part of his valuation, McConnell used a syringe to extract some of the liquid, decanted it into a tumbler, and, uh, drank it. He described it as “very brown,” stating, “I think it’s port. It’s port or red wine, or its full of rusty old nails and that’s rust.”

In 2019, television presenter Fiona Bruce had another chat on the air with McConnell, where she had the unenviable task of revealing to the glass specialist the results of an analysis of the bottle’s contents conducted by researchers at Loughborough University. The bottle, you see, had turned out to be a witch bottle, which meant that the liquid within the bottle was composed of “urine, a tiny bit of alcohol, and one human hair.”

Yikes.

To be fair, McConnell drank the mystery liquid in the first place mostly for shock value; according to him, he was “always the naughty boy at school” and considered the situation “too good an opportunity to miss.”

Would that we were all so confident.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!

[Photo via Ethan Doyle White, archive.org/Wikimedia Commons, available under a CC BY-SA 4.0 Creative Commons license.]